What 9/11 Wrought

The former editor of the New York Times considers the effects of the terrorist attacks on the 10th anniversary of the fateful day

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/September-11-Osama-bin-Laden-reaction-631.jpg)

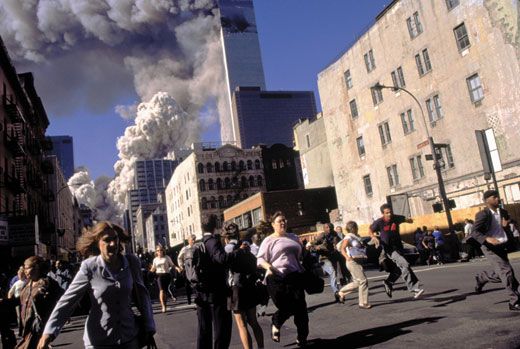

The military had a name for it—“asymmetric warfare.” But until 9/11 hardly anyone imagined how surreal and coldblooded, how devastating, it could actually be: that 19 would-be suicides from distant parts, armed only with box-cutters, their leaders trained to fly but not land airliners, could bring the greatest military power the world had seen momentarily to its knees, with a loss of lives on that perfect late-summer morning surpassing that inflicted by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. With video clips edited to remove scores of bodies flying through the air, what was shoved in our faces on our TV screens hundreds of times in the days that followed was still close enough to the full horror: the planes serenely cruising into the towers over and over again, the vile, bilious clouds of smoke and debris that repeatedly engulfed the buildings as they kept falling; the feeling of utter vulnerability, heightened by images of further wreckage and loss at the Pentagon and in a Pennsylvania field; all followed by rage.

Ten years on, all of that and more—including the spontaneous surge of flag-flying patriotism and civic determination—can instantly be recalled by anyone who experienced it the first time. What’s harder to recall is the sense that it was only the beginning, that “the homeland,” as the authorities came to call it, would surely be assaulted on a wide variety of fronts. A flurry of anthrax attacks of mysterious origin deepened such premonitions. Think-tank scenarists cataloged a broad range of nightmare possibilities: suicide bombers boarding subways, infiltrating malls and multiplexes; the millions of containers unloaded in our harbors available to deliver dirty bombs; our chemical plants and the rail lines that serve them wide open to attack; our great bridges brought down. Worst of all, small nuclear devices containing radioactive material smuggled from Russian, Pakistani or (so some imagined) Iraqi stockpiles that could be hand-carried into our population centers, places like Times Square, and detonated there, causing mass panic and death on a scale that would make 9/11 look like a practice run. For a time, it seemed that none of this was impossible, even improbable, and we needed to act. What was initially branded the Global War on Terror—a struggle without geographic or temporal limits—was the result.

It may not be inappropriate on this anniversary to acknowledge that we overreacted and overreached, but that wasn’t so apparent a decade ago. Hardly anyone imagined then that all this time could pass—a period longer than our active involvement in World War II and the Korean War combined—with no large-scale recurrence of the original outrage on our territory. Other than a shooting rampage on a Texas military base, the most visible attempts have been failures: a shoe bomb on a trans-Atlantic flight, a car bomb off Broadway, a young Nigerian who sat aboard a Detroit-bound airplane with plastic explosives hidden in his jockey shorts. While we mourn the thousands killed and grievously wounded in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, the hard truth is that the more privileged and better educated we are, the less likely we are to have any direct acquaintance with them or their families. At the end of the decade, many of us pay lower taxes than ever before and have suffered no worse inconvenience than having to shed our shoes and, sometimes, belts as we pass through airport checkpoints. Beyond that, how have we been affected, how changed?

One answer that’s plausibly advanced is that our civil liberties have been eroded and our concern for individual rights—in particular, the rights of those we deem alien—has been coarsened by the steps our government has felt impelled to take to protect us from lurking threats: using new technology to sort and listen to phone calls by the millions without judicial warrants; rounding up and deporting Muslim immigrants by the thousands when there was anything dubious about their status; resorting to humiliation, physical stress and other “enhanced” methods of interrogation, sometimes amounting to torture, in cases of supposedly “high-value” terrorism suspects; making new claims for the authority of the executive branch to wage war in secrecy (including the breathtaking claim that our president had the constitutional authority to imprison indefinitely, without trial, any person on the planet he deemed an “unlawful enemy combatant”). One can debate the extent to which these things have happened or continue to happen. That’s one set of questions that might have been addressed had not proposals to appoint a nonpartisan commission to explore them been permanently shelved. Even so, lacking the authoritative narrative such a commission might have provided, we can still ask whether we’ve been affected or changed. Could it be that we don’t really mind the blurriness, that whatever was done secretly in the name of our security happened with our silent assent?

That’s a question I started asking myself on a reporting trip to Guantánamo in 2002, less than a year after the American naval base in Cuba was transformed into a warehouse for supposed terrorists rounded up on the Afghan-Pakistani frontier. Many of the guards had worked as correctional officers in their civilian lives. When I asked to meet some of them, I was introduced to two women normally employed in state prisons in Georgia. The harsh conditions in which the supposed terrorists were held, they told me, were a little harder than normal “segregation” for troublesome prisoners in the Georgia system, but not nearly so hard as Georgia-style “isolation.” I took this to be expert testimony. It helped me realize how little we’re normally inclined to question decisions taken, so we’re told, in the interest of our own security. If there was no big difference between prison conditions in Georgia and Guantánamo, who but a certified bleeding heart could call into question the guidelines for treatment of “terrorists” classed by a Pentagon spokesman as “the worst of the worst”?

Years later, we’d be told there was no hard evidence linking at least one-fifth—and possibly many more—of the Guantánamo detainees to terrorist movements. This belated coming to grips with the facts of each case could have been written off as carelessness were it not for the foresight displayed by members of Congress who legislated a provision barring lawsuits by Guantánamo detainees on any grounds. Suspicion alone, it seemed, was enough to keep them in the category of “the worst,” if not “worst of the worst.”

Beyond the constitutional, legal and even moral issues bound up in the matter of prisoner treatment, there’s the question of what this tells us about ourselves. Here again, we learn that we’ve cultivated a certain unacknowledged hardheartedness in our response to the enduring outrage of 9/11, that we’ll tolerate a large amount of “collateral damage” when it occurs out of view, far from our shores. By the time George W. Bush stood for re-election, most voters knew enough to understand that the invasion of Iraq had proved a questionable response to the events of that searing September morning; that the war, which was supposed to be over in months, was not going well, with no end in sight; and there was irrefutable evidence of prisoner humiliation and abuse, amounting to torture, at Abu Ghraib prison and elsewhere. From all this, key swing voters apparently concluded that in defense of the homeland, the president was more likely to hit back too hard than too softly. Evidence that such conclusions worked in his favor could be found in the failure of his opponent to bring up torture as an issue. Polling, it could be surmised, had shown that a referendum on this question would favor the candidate who coupled an assurance that the United States never resorts to torture with an assurance that he’d do whatever it took to protect the country. The American people, the president’s strategists evidently concluded, wanted it both ways. If our contradictions were not called to our attention, we were as capable as any other population of double-think, the survival art of holding two conflicting thoughts in our minds.

Even after we elected a president with the middle name Hussein and the proclaimed intention of closing the prison at Guantánamo, we continued to want it both ways. Guantánamo stayed open after members of Congress from the new president’s own party deserted him when he proposed moving the remnant of detainees there—those regarded as too dangerous to be freed—to a super-maximum-security prison in Illinois. Similarly, plans to bring the admitted mastermind of the 9/11 attacks to Manhattan to stand trial in a federal court had to be abandoned. A broad consensus formed around the notion that none of these people could be allowed to set foot in our land if their mere presence here entitled them to constitutional protections we routinely extend to drug traffickers, serial killers and sexual predators. Military justice was good enough—possibly too good—for terrorists who schemed to take innocent lives by the thousands.

In more ways than one, such distancing has been a strategy. The primary point of the global war, after all, had been to pursue and engage terrorists or would-be terrorists as far as possible from our shores. After nearly ten years in Afghanistan and eight in Iraq, our war planners may say the world is better without the Taliban in Kabul or Saddam Hussein in Baghdad, but it’s the conclusions Afghans and Iraqis will draw that should count, after years of living with the possibility of sudden death or ghastly injury to themselves or their loved ones. That’s to acknowledge that many more Afghans and Iraqis have died in our war than Americans. Probably it could not have been otherwise, but that obvious calculation is one we seldom have the grace to make. We pride ourselves on our openness and plain speaking, but we have shown we can live with a high degree of ambiguity when it serves our interests; for instance, in our readiness to turn a blind eye to inimical efforts of our allies—a Saudi autocracy that pours untold millions into proselytizing campaigns and madrassas on behalf of militant Wahhabi Islam, and the Pakistani military, which allowed the worst examples of nuclear proliferation on record to be carried out on its watch, which still sponsors terrorist networks, including some that have clashed with our troops in Afghanistan, and which almost certainly harbored Osama bin Laden until he was hunted down this past May by Navy Seals in a garrison town about an hour’s drive from Islamabad. We need access to Saudi oil, just as we need Pakistani supply routes to Afghanistan and tacit permission to conduct drone attacks on terrorist enclaves on the frontier. These are matters that we, as a people, inevitably leave to hardheaded experts who are presumed to know our interests better than we do.

A skeptical journalist’s way of looking at the past decade leaves out much that might well be mentioned—the valor and sacrifice of our fighters, the round-the-clock vigilance and determination (not just the transgressions) of our thousands of anonymous counterterrorists, the alacrity with which President Bush reached out to Muslim Americans, his successor’s efforts to live up to his campaign pledges to get out of Iraq and turn the tide in Afghanistan. That said, if history permitted do-overs, is there anyone who would have gone into Iraq knowing what we now know about Saddam’s defunct programs to build weapons of mass destruction, let alone the level of our casualties, sheer cost or number of years it would take to wind up this exercise in projecting our power into the Arab world? True, under various rubrics, our leaders offered a “freedom agenda” to the region, but only a propagandist could imagine that their occasional speeches inspired the “Arab spring” when it burst forth this year.

As we enter the second decade of this struggle, we have gotten out of the habit of calling it a global war. But it goes on, not limited to Afghanistan and Iraq. How will we know when it’s over—when we can pass through airport security with our shoes on, when closing Guantánamo is not unthinkable, when the extraordinary security measures embodied in the renewed Patriot Act might be allowed to lapse? If, as some have suggested, we’ve created a “surveillance state,” can we rely on it to tell us when its “sell by” date has arrived? On the tenth anniversary of 9/11, it’s possible, at least, to hope that we’ll remember to ask such questions on the 20th.

Joseph Lelyveld, executive editor of the New York Times from 1994 to 2001, has written the Gandhi biography Great Soul.