What Extreme Flooding in Yellowstone Means for the National Park’s Gateway Towns

These communities rely almost entirely on tourism for their existence—yet too much tourism, not to mention climate change, can destroy them

:focal(2000x1505:2001x1506)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/a1/60a1386f-a07d-4d1c-843f-ebf4068e030d/gettyimages-1241307104.jpg)

It had been an unusually warm early June in Yellowstone National Park, with temperatures in the 70s. Then a weekend storm intensified quickly, dropping a month’s worth of precipitation on the park in little more than a day. The rivers and creeks were already running high, filled with melting snow from an above-average snowpack. By Monday, the Gardner River—whose headwaters are on the west side of the park, in the Gallatin Mountains—was a muddy, rushing torrent.

As it churned down the Gardner Canyon below Mammoth Hot Springs, the river took chunks of the adjacent roadway along with it. Choked with debris, the floodwaters joined the Yellowstone River at the foot of the canyon; the surge pushed on more than 50 miles north, inundating Yankee Jim Canyon, Paradise Valley and the town of Livingston.

Conditions were similar across the park, as creeks and waterways rose to record-breaking levels, covering roadways and sweeping away bridges. On Monday, Yellowstone’s superintendent, Cam Sholly, announced the closure of all five of Yellowstone’s inbound entrances and the evacuation of most tourists from the area.

Current conditions of Yellowstone’s North Entrance Road through the Gardner Canyon between Gardiner, Montana, and Mammoth Hot Springs.

— Yellowstone National Park (@YellowstoneNPS) June 13, 2022

We will continue to communicate about this hazardous situation as more information is available. More info: https://t.co/mymnqGvcVB pic.twitter.com/S5ysi4wf8a

The extreme weather took a heavy toll on the town of Gardiner, Montana, which sits at the confluence of the Gardner (more on the spelling discrepancy later) and Yellowstone rivers. Floodwaters cut off Gardiner’s almost 900 residents from both Livingston and the park’s headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs, leaving them without power and drinkable water for several days.

“The road that I took from Yellowstone Park to [Gardiner], I drove on it probably 10:30 p.m. Sunday night,” Dawson Killen, a tourist from Texas who found herself stranded in Gardiner, told ABC Fox Montana. “By the time I woke up [Monday], the road didn’t exist anymore.”

This early summer flood was the latest in a series of dynamic events that have shaped Gardiner over the past two centuries. It shows how the very conditions that create thriving, successful gateway towns—defined as communities located just outside of national parks and historic sites—make them vulnerable to destruction.

What is now the town of Gardiner sits between the Gallatin and Absaroka mountain ranges. For thousands of years, the two rivers that rush down from the Yellowstone caldera and into this valley drew bison, elk and wolves—and the Apsaalooké (Crow), northern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Shoshone-Bannock and other Indigenous hunters who followed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/d1/ded10914-3b25-45d5-a8b4-b01cb6b8c86e/service-pnp-habshaer-mt-mt0100-mt0178-photos-344892pv.jpeg)

The first white man to take up residence at the confluence was Johnson Gardner, an American Fur Company trapper who caught beavers along the Yellowstone River in the 1830s. The area became known as Gardner’s Hole, in part due to legendary guide Jim Bridger, who used the name when he brought the Washburn-Langford-Doane expedition to Yellowstone in 1870. The name of the campsite (but not the river) was misspelled in the expedition’s accounts, and in the official government report of geologist Ferdinand Hayden, who brought the first federally funded scientific team into Yellowstone the following year.

Hayden’s survey led to the passage of the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act in 1872, preserving more than one million acres in the Yellowstone Basin and creating the first national park in the world. Within the year, entrepreneurs had built a toll road from Bozeman, Montana, to Gardiner and up to Mammoth Hot Springs. Settlers arrived and built a restaurant and bakery, post office, schoolhouse, barber shop, saloon, general store and hotel. But the area was still difficult to reach; only a few hundred tourists came through Gardiner to visit Yellowstone in the next ten years.

In 1882, the Northern Pacific Railroad reached the town of Livingston, and the hundreds of tourists became thousands, disembarking at Livingston and then taking stagecoaches to Gardiner and the park. It wasn’t until the completion of a Northern Pacific spur line—a short extension of the track from the main line at Livingston to the park’s northern entrance—in 1902, however, that Gardiner’s status as the park’s first gateway town was secured.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/a4/ffa4244a-89e5-4697-9ba1-35935a0f7221/northernpacificdepotgardiner-haynes.jpeg)

As the first issue of the Gardiner Wonderland declared in May 1902, “This town is the supply point of the surrounding country, and headquarters for most of the team work and freighting in and about the park.”

By then, officials had established the park’s headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs, one of Yellowstone’s premier attractions. But visitors also wanted to see the upper and lower falls of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, as well as Old Faithful and the other wonders of the geyser region.

Park personnel constructed two “loop roads” connecting these sites and several new entrances, which linked the park to communities that would become additional gateway towns: Jackson Hole (south) and Cody (east) in Wyoming and West Yellowstone (west) and Cooke City (northeast) in Montana. The western entrance quickly became the park’s most popular. After 1902, when the southern entrance was completed, Jackson Hole and Gardiner vied for the second spot.

To promote Gardiner’s role as the first gateway—and to provide tourists entering the park there with a dramatic experience—town leaders and United States Army officials (who oversaw Yellowstone at the time) built a 50-foot-tall basalt arch in 1903. President Theodore Roosevelt, who was visiting Yellowstone that spring, laid the cornerstone and gave a short speech.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/4a/de4a5157-b759-417b-b0a3-5ce6aea5f404/milky_way_rising_over_roosevelt_arch_5517_2_34078769463.jpg)

“The Yellowstone Park is something absolutely unique in the world so far as I know,” Roosevelt told a cheering crowd. “Nowhere else in any civilized country is there to be found such a tract of veritable wonderland made accessible to all visitors.”

In the almost 120 years since the arch’s dedication, Gardiner has played an important role in making the park accessible, pivoting to meet escalating numbers of visitors and adapt to transportation revolutions. In 1915, officials authorized automobiles’ entry into the park. Gas stations, garages and auto repair shops quickly replaced stables, barns and liveries. The town widened its streets, and the commercial corridor expanded.

In 1948, as train ticket sales declined due to the American embrace of the automobile, the Northern Pacific Railroad decided to end passenger rail service to Gardiner. That same year, visitation to Yellowstone reached one million for the first time; an estimated 18 to 20 percent of these travelers came through Gardiner.

Gardiner is in many ways typical of Yellowstone’s gateway communities—and other such towns across the nation—in its long history of tourism and economic growth stemming from close relationships with iconic American landscapes. It is unique, however, in being the site of much of Yellowstone National Park’s “official” infrastructure. Due to Gardiner’s proximity to park headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs, the park built a Heritage and Research Center that houses manuscript, book and object collections related to Yellowstone’s history there in 2005. Yellowstone Forever, the official nonprofit partner of the park that supports education and fundraising projects, is also based in Gardiner.

These places draw visitors, as does the town itself. Gardiner’s location at the end of the bucolic Paradise Valley and its quaint main street perched high above the Yellowstone River make it, as the town’s chamber of commerce likes to say, “nature’s favorite entrance.” It’s also the only gateway community to offer year-round entrance to Yellowstone, giving business leaders an advantage in attracting shoulder season visitors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f0/26/f026454c-7460-4498-8bf5-e73ef0c16baa/mammoth_hot_springs_and_gardiner_mt_from_bunsen_peak_trail_35632155051.jpeg)

These are all benefits for Gardiner and its residents. But gateway communities balance on the sharpest segment of a double-edged sword. They rely almost entirely on tourism for their existence, yet too much tourism can destroy them.

In 2013, for example, local, state and federal agencies poured money into infrastructure improvements in Gardiner to prepare for the National Park Service’s 2016 centennial celebrations. While residents of the town appreciated the new sidewalks, lighting and tax revenue that resulted from the program, some came to resent the accompanying uptick in tourist traffic, according to a 2018 survey by the University of Montana. The town was flourishing, but it was also more crowded and less peaceful.

The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these problems. In spring 2020, quarantine orders cut off the flow of tourists to Yellowstone and threw Gardiner and the park’s other gateway communities into economic disarray. Then, the surge of tourists heading back into the region in summer 2020 and 2021 put stress on hotels and restaurants experiencing massive labor shortages, as well as hospitals dealing with out-of-towners who contracted Covid-19 while on the road. The pandemic also brought a large new population of transplants to the region, most of them white-collar workers who could log into their jobs from anywhere with a decent Wi-Fi signal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/a8/d8a8b6d0-0e42-46be-b69b-15db6c4e3f30/fvqu4zzwaaeh8js.jpeg)

As a result of this tourism boom, housing prices skyrocketed, and an increasing number of apartments and houses in Gardiner were turned into Airbnbs and other short-term rentals, making it difficult for people who want to work at the park and its related businesses to find a place to live. The situation has created friction between locals and visitors.

These demographic shifts, like every aspect of Gardiner’s history, are both beneficial and damaging to its prospects. Gardiner’s status as a gateway community is the reason for its success but also makes the town vulnerable to larger changes in government policy, technological innovation and global events. This weekend’s flood also points to the fact that Gardiner is vulnerable to climate change.

Last summer, a study of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem found that while average precipitation across the region has not changed significantly since 1950, temperatures have risen steadily, resulting in more rain (rather than snow) at higher elevations in late spring. Though the recent flooding was unprecedented, the conditions that created it will likely become increasingly common: accelerated snowmelt, combining with spring storms bringing too much rain for Yellowstone’s creeks and rivers to handle. Even if Montana and Wyoming residents take steps to mitigate climate change in the next few years, the report’s authors point out, temperatures will continue to rise, and more extreme weather events will take place.

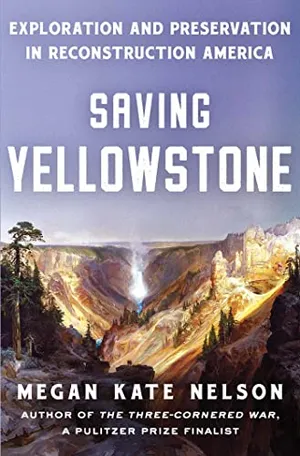

Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America

From Megan Kate Nelson, historian and critically acclaimed author of "The Three-Cornered War," comes the captivating story of how Yellowstone became the world’s first national park in the years after the Civil War

The havoc that the Gardner River wreaked on the canyon road to Mammoth doesn’t bode well for the town. The road into the park will probably be closed until next year at the earliest. Without access to Yellowstone, tourists are unlikely to travel all the way down to Gardiner just to hike or go whitewater rafting. The local economy will be devastated in the short term. The park itself will also undergo changes; without the Gardiner entrance to bring visitors into the northern part of Yellowstone, rangers and other staff will face overcrowding and traffic jams throughout the rest of the park.

The challenges to recovery will be immense. Gardiner’s residents—and the National Park Service—cannot ignore the impact of recent demographic shifts or the strong likelihood of a more volatile climate in the future. What Gardiner’s long history shows, however, is that this weekend’s floods are one turbulent moment in a series of such moments. To remain “nature’s favorite entrance” to Yellowstone, this gateway town will have to adjust, yet again, to momentous changes occurring on the edges of America’s first national park.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.