What Frederick Douglass Had to Say About Monuments

In a newly discovered letter, the famed abolitionist wrote that ‘no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth’

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/ca/7bcafd77-1066-4b17-af91-5ff46c034935/gettyimages-1223462254.jpg)

Frederick Douglass, with typical historical foresight, outlined a solution to the current impasse over a statue he dedicated in Washington, D.C., in 1876. Erected a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol, in a square called Lincoln Park, the so-called Emancipation Memorial depicts Abraham Lincoln standing beside a formerly enslaved African-American man in broken shackles, down on one knee—rising or crouching, depending on who you ask. As the nation continues to debate the meaning of monuments and memorials, and as local governments and protesters alike take them down, the Lincoln Park sculpture presents a dispute with multiple shades of gray.

Earlier this month, protestors with the group Freedom Neighborhood rallied at the park, managed by the National Park Service, to discuss pulling down the statue, with many in the crowd calling for its removal. They had the support of Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District’s sole representative in Congress, who announced her intention to introduce legislation to have the Lincoln statue removed and “placed in a museum.” Since then, a variety of voices have risen up, some in favor of leaving the monument in place, others seeking to tear it down (before writing this essay, the two of us were split), and still others joining Holmes Norton’s initiative to have it legally removed. In an essay for the Washington Post, Yale historian and Douglass biographer David W. Blight called for an arts commission to be established to preserve the original monument while adding new statues to the site.

It turns out Frederick Douglass had this idea first.

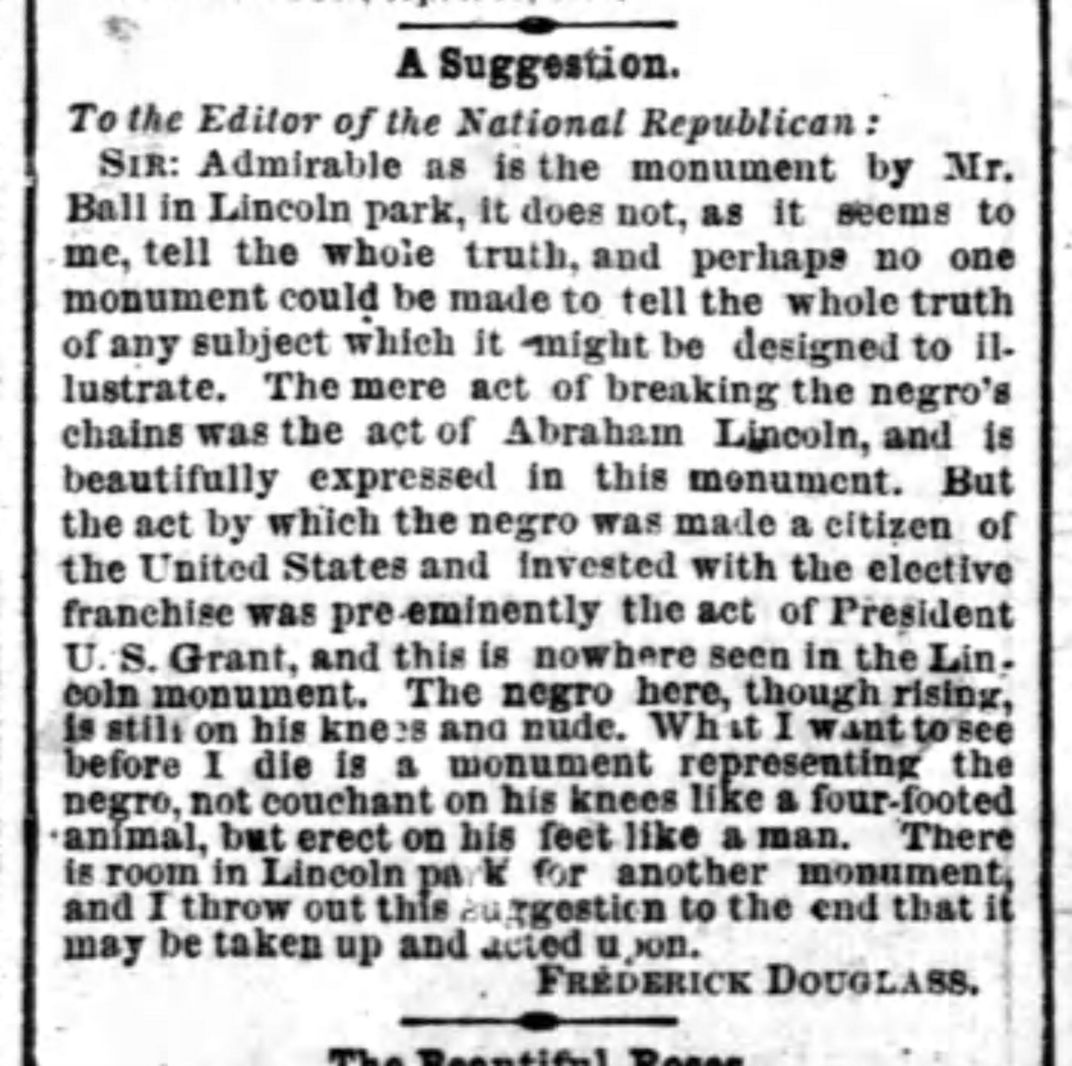

“There is room in Lincoln park [sic] for another monument,” he urged in a letter published in the National Republican newspaper just days after the ceremony, “and I throw out this suggestion to the end that it may be taken up and acted upon.” As far as we can ascertain, Douglass’s letter has never been republished since it was written. Fortunately, in coming to light again at this particular moment, his forgotten letter and the details of his suggestion teach valuable lessons about how great historical change occurs, how limited all monuments are in conveying historical truth, and how opportunities can always be found for dialogue in public spaces.

In the park, a plaque on the pedestal identifies the Thomas Ball sculpture as “Freedom’s Memorial” (Ball called his artwork “Emancipation Group”). The plaque explains that the sculpture was built “with funds contributed solely by emancipated citizens of the United States,” beginning with “the first contribution of five dollars … made by Charlotte Scott a freed woman of Virginia, being her first earnings in freedom.” She had the original idea, “on the day she heard of President Lincoln’s death to build a monument to his memory.”

With this act, Scott had secured immortality; her 1891 obituary in the Washington Evening Star, eulogized that her “name, at one time, was doubtless upon the lips of every man and woman in the United States and is now read by the thousands who annually visit the Lincoln statue at Lincoln Park.” Indeed, the Washington Bee, an important black newspaper of the era, proudly referred its readers to “the Charlotte Scott Emancipation statue in Lincoln Park.”

Scott’s brainchild and philanthropic achievement today stands surrounded: first by protective fencing, then by armed guards wearing Kevlar vests, then by protesters, counter-protesters, onlookers, neighbors and journalists, and finally by a nation in which many are seeing the legacies of slavery for the first time. Not since 1876, at least, has the imagery of kneeling—as torture and as protest—been so painfully and widely seen.

Ironically, Ball had changed his original design in an attempt to convey what we now recognize as the “agency” of enslaved people. Having first modeled an idealized, kneeling figure from his own white body, Ball was persuaded to rework the pose based on a photograph of an actual freedman named Archer Alexander. The new model had already made history as the last enslaved Missourian to be captured under the infamous Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (the arrest took place in 1863, in the middle of the Civil War). A white speaker at the dedication recounted the statue’s redesign. No longer anonymous and “passive, receiving the boon of freedom from the hand of the liberator,” the new rendering with Archer Alexander depicted “an AGENT IN HIS OWN DELIVERANCE … exerting his own strength with strained muscles in breaking the chain which had bound him.” Thus the statue imparted a “greater degree of dignity and vigor, as well as of historical accuracy.”

Few today see it that way—and neither did Frederick Douglass in 1876.

Even as he delivered the dedication address, Frederick Douglass was uncomfortable with the statue’s racial hierarchy and simplistic depiction of historical change. Having known and advised the President in several unprecedented White House meetings, Douglass stated bluntly to the assembled crowd of dignitaries and ordinaries that Lincoln “was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.”

Yet, Douglass acknowledged that Lincoln’s slow road to emancipation had been the fastest strategy for success. “Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible,” Douglass orated. “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

Douglass saw Lincoln not as a savior but as a collaborator, with more ardent activists including the enslaved themselves, in ending slavery. With so much more to do, he hoped that the Emancipation statue would empower African Americans to define Lincoln’s legacy for themselves. “In doing honor to the memory of our friend and liberator,” he said at the conclusion of his dedication speech, “we have been doing highest honors to ourselves and those who come after us.”

That’s us: an unsettled nation occupying concentric circles around a memorial that Douglass saw as unfinished. The incompleteness is what prompted the critique and “suggestion” he made in the letter we found written to the Washington National Republican, a Republican publication that Douglass, who lived in D.C., would have read. “Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln park,” he began, “it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate.”

Douglass had spoken beneath the cast bronze base that reads “EMANCIPATION,” not “emancipator.” He understood that process as both collaborative and incomplete. “The mere act of breaking the negro’s chains was the act of Abraham Lincoln, and is beautifully expressed in this monument,” his letter explained. But the 15th Amendment and black male suffrage had come under President Ulysses S. Grant, “and this is nowhere seen in the Lincoln monument.” (Douglass’ letter may be implying that Grant, too, deserved a monument in Lincoln Park; some newspaper editors read it that way in 1876.)

Douglass’s main point was that the statue did not make visible “the whole truth” that enslaved men and women had resisted, run away, protested and enlisted in the cause of their own freedom. Despite its redesign, the unveiled “emancipation group” fell far short of this most important whole truth.

“The negro here, though rising,” Douglass concluded, “is still on his knees and nude.” The longtime activist’s palpable weariness anticipated and predicted ours. “What I want to see before I die,” he sighed, “is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

And so his suggestion: Lincoln Park, two blocks wide and one block long, has room for another statue.

Nearly a century later, Lincoln Park would indeed get another statue—of Mary McLeod Bethune, the African American activist and educator, with a pair of frolicking children—placed in 1974 at the other end of the park, as if the three were to be kept as far away as possible from their problematic predecessor. Lincoln’s statue was even rotated 180 degrees to face Bethune when her statue was installed; nonetheless, these separate memorials are not in dialogue, figuratively or spatially.

Douglass’s solution was not to remove the memorial he dedicated yet promptly criticized, nor to replace it with another one that would also fail, as any single design will do, to “tell the whole truth of any subject.” No one memorial could do justice, literally, to an ugly truth so complex as the history of American slavery and the ongoing, “unfinished work” (as Lincoln said at Gettysburg) of freedom. Nobody would have needed to explain this to the formerly enslaved benefactors like Charlotte Scott, but they made their public gift just the same.

And yet if the statue is to stand there any longer, it should no longer stand alone. Who would be more deserving of honor with an additional statue than the freedwoman who conceived of the monument? In fact, Charlotte Scott attended its dedication as a guest of honor and was photographed about that time. A new plaque could tell Archer Alexander’s story. Add to these a new bronze of Frederick Douglass, the thundering orator, standing “erect on his feet like a man” beside the statue he dedicated in 1876. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should juxtapose Douglass and Lincoln, as actual historical collaborators, thus creating a new “Emancipation Group” of Scott, Douglass, Lincoln, Archer Alexander—and Bethune.

This would create an entirely new memorial that incorporates and preserves, yet redefines, the old one, just as the present is always redefining the past. In a final touch, add to the old pedestal the text of Douglass’s powerful yet succinct letter, which will charge every future visitor to understand “the whole truth” of the single word above, cast in bronze – EMANCIPATION – as a collaborative process that must forever “be taken up and acted upon.”

Scott A. Sandage is Associate Professor of History at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa., and Jonathan W. White is Associate Professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University, Newport News, Va. Follow them on Twitter at @ScottSandage and @CivilWarJon.