What Happened on John Lennon’s Last Day

The former Beatle had a packed schedule as he finalized a new song and posed for some final photographs that would become iconic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/85/4f8565e1-4e16-4203-aca7-e4bb2a448f20/gettyimages-515543592.jpg)

“We woke up to a shiny blue sky spreading over Central Park,” Yoko Ono later recalled. “The day had an air of bright eyes and bushy tails.” And December 8, 1980 was destined to be a busy day at that, given the Lennons’ dawn-to-dusk schedule, which included a photo shoot, an interview, and another bout working on their song “Walking On Thin Ice” at the Record Plant that evening. After the couple took their breakfast at Café La Fortuna, John made his way over to Viz-à-Viz for a hair quick trim. When he stepped out of the salon that morning, he sported a retro style akin to his pre-fame look.

Back at their apartment in the Dakota building on the Upper West Side, photographer Annie Leibovitz was preparing to complete the photo shoot that they had begun the previous week. Recording executive David Geffen had been working diligently behind the scenes to ensure that John and Yoko would be the next Rolling Stone cover story, but editor Jann Wenner had been trying to engineer a John-only cover photograph. For her part, Leibovitz would never forget arriving at the Lennons’ apartment that morning. “John came to the door in a black leather jacket,” she recalled, “and he had his hair slicked back. I was thrown a little bit by it. He had that early Beatle look.”

Knowing that they needed to come up with something extraordinary to land the cover shot, Leibovitz had something special in mind. In Leibovitz’s mind, a concept began to develop around the withering place of romantic love in contemporary culture. By way of contrast, she had been inspired by the black-and-white Double Fantasy album cover depicting John and Yoko in a gentle kiss. “In 1980,” she recalled, “it felt like romance was dead. I remembered how simple and beautiful that kiss was, and I was inspired by it.” To this end, she began to envision a vulnerable rendering of the famous couple. “It wasn’t a stretch to imagine them with their clothes off because they did it all the time,” she thought.

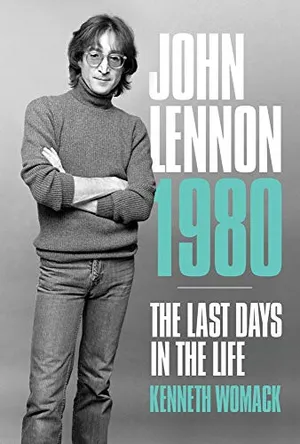

John Lennon 1980: The Last Days in the Life

Lennon's final pivotal year would climax in several moments of creative triumph as he rediscovered his artistic self in dramatic fashion. With the bravura release of the Double Fantasy album with wife Yoko Ono, he was poised and ready for an even brighter future only to be wrenched from the world by an assassin's bullets.

Only this time, Yoko wasn’t having it. She offered to remove her top as a form of compromise, but then John and Leibovitz hit upon the idea of a naked John embracing a fully clothed Yoko in a fetal pose. Leibovitz photographed them lying on the cream-colored carpet in their living room.

After Leibovitz took a Polaroid test shot, John could barely contain himself. “This is it!” he exclaimed. “This is our relationship!” That day, Leibovitz only shot a single roll of film, including the cover photo and various images of John posing around the apartment. By the time that Leibovitz completed her photo shoot, John was already due downstairs in Yoko’s Studio One office, where a team from RKO Radio led by on-air personality Dave Sholin had an unforgettable experience. “You get those butterflies, you get excited,” Sholin recalled, “but John loosened everybody up immediately.”

Within a matter of moments, John was cracking wise about his daily routine – “I get up about six. Go to the kitchen. Get a cup of coffee. Cough a little. Have a cigarette” – and watching “Sesame Street” with the Lennons’ five-year-old son, Sean: “I make sure he watches PBS and not the cartoons with the commercials – I don’t mind cartoons, but I won’t let him watch the commercials.” All the while, Sholin had become fascinated with John and Yoko. “The eye contact between them was amazing. No words had to be spoken,” Sholin recalled. “They would look at each other with an intense connection.”

As the interview pressed on, John began reflecting on the recent celebration of his 40th birthday and encroaching middle-age. “I hope I die before Yoko,” he said, “because if Yoko died I wouldn’t know how to survive. I couldn’t carry on.” Yet his thoughts were always buoyed, it seemed, by an inherent optimism. In this vein, he had begun to perceive his music as part of a larger continuum. “I always considered my work one piece, whether it be with [the] Beatles, David Bowie, Elton John, Yoko Ono,” he told Sholin, “and I consider that my work won’t be finished until I’m dead and buried, and I hope that’s a long, long time.” And speaking of his collaborations, John made a point of noting that “there’s only been two artists I’ve ever worked with for more than a one night stand, as it were. That’s Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono. I think that’s a pretty damn good choice. As a talent scout, I’ve done pretty damn well.”

When the interview wrapped, Sholin and his RKO team took their leave and began carting their equipment—tape recorders, microphones, and the like—out to their chauffeured Lincoln Town Car in front of the Dakota’s porte-cochère. Hurrying to make their flight, they were stowing their equipment in the trunk when John and Yoko strolled out of the archway. When the Lennons stepped onto the sidewalk along West 72nd Street, the area around the entrance to the Dakota was unusually vacant. “Where are my fans?” John asked.

At that point, amateur photographer Paul Goresh walked up to show John the proofs from a recent visit he had made. As John scanned the photos, another fan walked up, sheepishly extending a copy of Double Fantasy and a pen in his direction. “Do you want me to sign that?” John asked. As he scrawled “John Lennon 1980” across the cover, Goresh snapped a photo of John and the fan, a bespectacled fellow in a rumpled overcoat. “Is that okay?” John asked, with his eyebrows raised. As the man edged away, John turned back to Goresh and shot him a quizzical look.

And that’s when John asked Sholin if the RKO team could give the couple a lift to the Record Plant. With Sholin’s good-natured urging, John and Yoko climbed into the backseat. As the car pulled away, Goresh saw John wave goodbye to him. Seizing the moment as their driver navigated the snarling Midtown traffic, Sholin resumed their conversation, asking John about his current relationship with Paul. For his part, John didn’t miss a beat, telling Sholin that their rift had been “overblown” and that Paul was “like a brother. I love him. Families – we certainly have our ups and downs and our quarrels. But at the end of the day, when it’s all said and done, I would do anything for him, and I think he would do anything for me.”

After they pulled up at the Record Plant, John and Yoko joined producer Jack Douglas upstairs. By this point, “Walking On Thin Ice,” a Yoko-composed song that John was helping record and produce, had evolved into a discothèque-friendly six-minute opus, complete with Yoko’s eerie vocal sound effects, spoken-word poem, and Lennon’s wailing guitar solo, with a much-needed assist from Douglas on the whammy bar. John was ecstatic as he listened to the mix in all of its glory. “From now on,” he told Yoko, “we’re just gonna do this. It’s great!” – adding that “this is the direction!”

When Geffen arrived, they listened to the latest mix of “Walking On Thin Ice.” John proclaimed that “it’s better than anything we did on Double Fantasy,” adding “let’s put it out before Christmas!” Recognizing that the holiday season was scarcely two weeks away, Geffen countered, “Let’s put it out after Christmas and really do the thing right. Take out an ad.” Now he had John’s undivided attention. “An ad!” said John, turning to Yoko. “Listen to this, Mother, you’re gonna get an ad!” Geffen shifted the conversation back to Double Fantasy, informing the Lennons that the album was continuing to climb the U.K. charts. As he made his pronouncement, Yoko caught the music mogul’s eye. “Yoko gave me this real funny look,” Geffen recalled, “like it better be number one in England. That was the thing she was interested in, not for herself but because John wanted it so badly.”

Over the next few hours, Douglas and the Lennons made a few last-minute refinements on “Walking On Thin Ice.” Finally, they called it quits for the evening, having decided to meet bright and early the next morning to begin the mastering process. John and Yoko were exhausted, having worked almost nonstop over the past week on their new creation. They planned to grab a bite to eat – perhaps at the Stage Deli over on 7th Avenue and a few blocks away from Carnegie Hall

As they stepped into the elevator, John and Yoko were joined by Robert “Big Bob” Manuel, the Record Plant’s six-foot-six security guard. “John was so happy,” the bodyguard later remembered, “because Yoko was finally getting respect from the press. That meant the world to him.” On a whim, John asked Big Bob to join them for a late meal. “I’m sick to my stomach,” Big Bob replied, begging off. “I don’t feel good.” John placed his arm around the bodyguard’s shoulders. “Don’t worry,” he said. “You go home, feel better, we’ll do it another night.”

By the time John and Yoko had made their way downstairs from the Record Plant, they had decided that they wanted to go straight home and say goodnight to Sean, who was back in apartment 72 with his nanny. They could get a bite to eat later. After all, this was New York, “the city that never sleeps.” They stepped outside the building, where a limousine was parked right out front, ready and waiting to ferry the couple back to the Dakota.

Pulling away from the Record Plant, the limo made the short drive northward, rolling through Columbus Circle and up Central Park West before making the sharp left turn onto West 72nd Street, where a taxi cab was discharging a customer in front of the Dakota. Forced to double-park, the limo coasted to a stop in front of the porte-cochère, where the building’s gaslights illuminated the night-time air. Yoko climbed out of the vehicle first and began walking towards the archway. John followed suit, strolling a few paces behind his wife and clutching a stack of cassettes, including the latest mix of “Walking On Thin Ice,” in his hand.

It was just after 10.45 p.m., relatively quiet, and still unseasonably warm. The night’s peacefulness was broken, however, when an assassin, the same man in the rumpled overcoat from earlier that day, shot and killed Lennon on the street in front of the Dakota.

Millions of American television viewers would learn the awful truth a short while later, when ABC sportscaster Howard Cosell interrupted the “Monday Night Football” matchup between the New England Patriots and the Miami Dolphins to deliver the news:

“We have to say it. Remember, this is just a football game. No matter who wins or loses. An unspeakable tragedy confirmed to us by ABC News in New York City. John Lennon, outside of his apartment building on the West Side of New York City, the most famous, perhaps, of all of the Beatles, shot twice in the back, rushed to Roosevelt Hospital, dead on arrival. Hard to go back to the game after that newsflash, which in duty bound, we had to take.”

Days later on Sunday, December 14, a ten-minute vigil was held at Yoko’s request, at 2 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. Across the globe, radio stations honored the occasion by going silent. It would be a means for anyone who hoped to celebrate John’s life to “participate from where you are,” in Yoko’s words. In his hometown of Liverpool, some 30,000 mourners gathered, while more than 50,000 fans assembled in Central Park for a somber remembrance of the man who had so proudly called New York City his home.

The author will speak at a Smithsonian Associates event on December 2.

Excerpted from John Lennon, 1980: The Last Days in the Life by Kenneth Womack. Copyright © 2020 by Omnibus Press (a division of the Wise Music Group). All rights reserved.

Kenneth Womack is a world-renowned music historian and author focused on the enduring cultural influence of the Beatles. He serves as a professor of English and popular music at Monmouth University.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.