What Happened When a Southern Airways Flight 242 Crashed in Sadie Burkhalter’s Front Yard

Her home became a makeshift hospital when she looked out her front door to a fiery inferno

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/4b/084b0b15-699c-4d89-9c30-73eb1c8eaa2d/ap_910562397383-wr.jpg)

For years afterward, the scent of jet fuel and scorched hair were powerful sensory cues that transported Sadie Burkhalter Hurst back in time to the day when fire and death invaded her tranquil world. “Most of the time,” she said 40 years later, “you don’t remember it until things trigger those memories. And so many things will bring back the memories. Burning hair will just make me sick at my stomach. The emotions come back. You don’t want them to, you don’t ask for them, but you can’t stop them. To this day I can smell the odors and I can hear the sounds. And I can see those people.”

On Monday, April 4, 1977, Sadie was a young mother of three boys living in the small community of New Hope, Georgia. That lovely spring afternoon, she stood in her living room and witnessed a scene almost out of a horror film. A man was running across her front yard toward her, frantically waving his arms, his clothing ablaze. Behind him, downed electrical wires snaked around charred bodies. A traumatized young man with red hair and badly burned hands had taken refuge in the yellow Cadillac parked in Sadie’s driveway. Another man, engulfed in flames, was running blindly toward the creek behind her house. In the midst of it all, a shimmering blue line painted on a fragment of metal was all that remained to identify the mangled fuselage of a Southern Airways DC-9-31 passenger plane that had just crashed into the Burkhalters’ quiet front yard.

**********

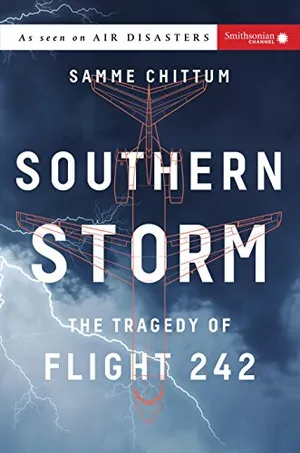

Southern Storm: The Tragedy of Flight 242

The gripping true tale of a devastating plane crash, the investigation into its causes, and the race to prevent similar disasters in the future.

Every airline chooses its livery colors with care and pride. In 1977, the most distinctive feature of the official livery for the Southern Airways fleet was that cobalt-blue band, emblazoned with the company’s name, which ran from the nose cone to the tail.

On that April day, at 3:54 p.m., a Southern Airways DC-9-31 carrying 81 passengers and four crewmembers took off under cloudy skies and in heavy rain from Huntsville International Airport, near Huntsville, Alabama, on its way to Atlanta. Sometime after 4 p.m., as it was flying over Rome, Georgia, the aircraft entered a massive thunderstorm cell, part of a larger squall line—a chain of storms that can brew up a wild and dangerous concoction of rain, hail, and lightning.

Far below to the east, in New Hope, the weather was idyllic. “It was an absolutely beautiful day,” recalled Sadie, who lived with her family in a brick ranch house set back from Georgia State Route 92 Spur (now Georgia State Route 381, known as the Dallas-Acworth Highway for the two cities it connects). “It was blue skies, white clouds, with a slight breeze, sun shining—just gorgeous.”

The warm spring weather had lured all three Burkhalter boys outside. Stanley, 14, and Steve, 12, were riding their bicycles up and down the driveway along with Tony Clayton, the son of New Hope volunteer fire chief John Clayton, who lived nearby. Eddie, two and a half, was peddling his tricycle along, trying to keep up with the older boys.

Sadie had just put on a pot of chili for supper when the phone rang. It was Emory, who worked in Atlanta for a firm that set shipping rates for trucking companies. When he was at work, he kept his office radio tuned to a station in Huntsville so that he could get a jump on news about threatening weather coming from the west on its way toward Paulding County. “By the time the weather hit Huntsville, we would get [the news] here before it got to the Atlanta radio stations,” explained Sadie. “He said, ‘Honey, we’ve got some bad weather coming. You need to get the kids in.’ So I hung up immediately. I walked down that front porch, and I called all the children. I said, ‘Boys, you need to come on in.’”

Steve could tell by the tone of her voice that she meant business. “She said we needed to come into the house, that there was gonna be some bad weather coming in, that we needed to prepare for that.” None of the children protested, he said, and Tony promptly left to go back home.

**********

Spring is tornado season in the South. The Burkhalters had an orderly preparation routine when twisters appeared out of nowhere and tore up everything in their path, and they had a convenient and safe refuge in their large basement. The boys wanted to help their mother get ready for whatever was on the way, be it a twister or a thunderstorm with lightning. “I immediately went and got the radio,” said Steve, “and Mother and Stanley got the batteries for it—just to kind of prepare for what would happen.” Sadie was alert but calm as she sat near the large picture window in the living room at the front of the house. While the boys tended the radio, she scanned the sky for black clouds that would signal the approach of a severe storm. “But we didn’t see any of that,” she said. “It just wasn’t there yet.”

These were the last normal moments in a day that would change her life, leave its mark on an entire community, and send shock waves across and beyond the state. The first warning of disaster came in the form of what Sadie later described as a “tremendous noise,” a roar emanating from somewhere nearby. What else could it be, she thought, but a twister bearing down on them? “Our eyes became huge,” she said, “and we just looked at each other, staring. We didn’t know what to do, and we ran immediately for the basement. The stairs were just a few feet away, and we ran down.”

Sadie was carrying Eddie, who was heavy in her arms, and hurrying down the steps when she was thrown forward by a powerful jolt that made the wooden risers bounce out from under her. “The impact knocked me down the stairs, and my feet just hit the cement.”

A tornado most often announces its arrival with a rumble that is often compared to the noise of a freight train. “But this was more like an explosion,” Steve recalled. “When the plane hit in the front yard, it was a strong and loud impact. It literally knocked us down the rest of the steps. So I knew it really wasn’t a tornado, but I just didn’t know what it was.”

Alarmed and determined to protect her children, Sadie handed Eddie to Steve and told the boys to go to one corner of the basement where the family took shelter in bad weather. “They did exactly what I planned for them to do.” As she made her way back upstairs, intent on closing the basement door to shut out any flying debris, she caught sight of something both eerie and frightening: flickering orange-red flames reflected in the glass storm door that opened onto the front porch.

From his vantage point in the basement, Steve saw the same flames through the windows at the top of the garage door. “I can remember seeing a bright orange light all around the windows and hearing loud noises, apparently from where the plane had just hit the ground.”

Although the storm door was shut, Sadie realized she had left the front door open in her haste to get down to the basement. She ventured into the living room to investigate. As she stood looking out through the storm door, she was astonished to see that her front yard had been transformed into an anteroom of hell. Tall pine trees were burning and crackling like torches. A noxious plume of black smoke billowed in all directions, making it hard to see beyond her property line. “The smoke was so thick that I couldn’t see the neighbors. I couldn’t see Miss Bell’s house. I couldn’t see the Claytons’ house, and I couldn’t see the Pooles’ house. And I thought they were all dead.”

She had only seconds to make sense of the calamity. “I saw a huge amount of smoke and flames,” but she also noticed something else: a metallic blue band. “I still didn’t know what it was. I just saw that thin blue line, and my mind registered that it was a plane.” And not a small private plane, but a jetliner. “It was a really big plane,” she said. “And I thought, ‘We can’t handle that here. We just don’t have enough help. There’s not enough fire departments, not enough ambulances. What are we gonna do?’”

**********

The first noise that the Burkhalters had heard was the DC-9 hitting Georgia State Route 92 Spur one-third of a mile south of their home. The plane came bouncing and hurtling down the two-lane highway, clipping trees and utility poles along the way and plowing into parked cars. Seven members of one family were killed when the plane struck their Toyota compact, which was parked in front of Newman’s Grocery; the plane also destroyed the store’s gas pumps before veering off the highway and cartwheeling onto the Burkhalters’ front yard, where it broke into five sections. One of the townspeople killed on the ground in the crash was an elderly neighbor of Sadie’s, Berlie Mae Bell Craton, 71, who died when a tire from the DC-9 flew through the air and struck her on the head as she stood in her front yard.

The tail had split open on impact, scattering passengers, luggage, and seats over the ground. The nose cone had separated from the rest of the plane and plowed into a five-foot ditch in the Burkhalters’ side yard, landing upside down. The DC-9’s captain, William Wade McKenzie, had been killed upon impact; the first officer, Lyman W. Keele Jr., who had been flying the plane, died while being airlifted to Kennestone Regional Medical Center in Marietta, Georgia.

Among the survivors was Cathy Cooper, one of the two flight attendants. She had briefly lost consciousness during the crash landing; she had been thrown sideways and violently shaken before her section of the plane finally came to rest upside down. She freed herself by releasing her seatbelt, dropping down onto what had been the ceiling of the plane. A nearby door was jammed shut, so she crawled in the semidarkness past hissing and popping electrical equipment until she saw a hole above her. She tried twice to climb out, falling back both times before succeeding the third time.

As Cooper emerged into the bright light of day, the 360-degree view that opened up before her was surreal and shocking. “When I got to the top of the aircraft and looked out, I was stunned. There is no other word to describe the view of the pieces of the plane burning, trees burning, passengers running in every direction. It was a nightmare scenario.” She was also surprised to find herself alive and unhurt. Her first thought was to get away from the plane, which she feared was about to explode. She jumped seven feet to the ground and ran from the burning wreckage.

Yet she knew she had to do everything in her power to assist the injured passengers. The best way to do that was to get to a telephone and summon help. “Your mind focuses on some trivial things. The telephone was a truly big issue at that point. I was just determined to find a phone, and so that’s why I went to the [Burkhalters’] house. Apparently the other passengers had gone up there also. I don’t know why. They might have been looking for a phone, too.”

From her vantage point behind her front door, Sadie Burkhalter was trying to make sense of what she was witnessing. The scene reminded her of historical newsreels she’d seen: “When I looked out the door and I saw all the people coming at me, I remember that it was just like the bit from the Hindenburg crash,” the wreck of the German passenger airship that had caught fire on May 6, 1937, while trying to dock at a naval air station in New Jersey. “You could see the Hindenburg falling in the background, the fire, the flames, and the people running at you. That’s what I saw that afternoon.”

Neither history nor her own life experiences had prepared Sadie for the role that chance chose for her: to be the first person encountered by more than a dozen traumatized and badly burned passengers fleeing the burning wreckage of what was the worst plane crash in the history of Georgia. The fire consuming the remnants of the plane would prove as lethal as the force of the impact. “I saw on my right a young man completely engulfed in flames, and he was dropping and rolling,” said Sadie. “And I thought, he’ll be all right, he’ll put himself out. And on the left was another man completely engulfed in flames, but he was still running [toward the creek] and he was waving his arms, and I didn’t have much hope that he was going to be able to put himself out.” Several more burned passengers had seen the creek behind the house and thrown themselves into its shallow, muddy waters.

The air was thick with the hot, roiling fumes generated by burning plastic and jet fuel. Barefoot, bewildered passengers emerged from the cloud of smoke and came stumbling toward the Burkhalters’ house. Clad in ragged, fire-singed remnants of clothing, they resembled sleepwalkers. Almost all were suffering from shock or smoke inhalation; tests later revealed many had high levels of carbon monoxide in their blood, which causes confusion and lightheadedness. Meanwhile, inside the basement, the three boys could see only confusing glimpses of what was taking place outside. “It was maybe two minutes [after the crash] I was looking out the windows,” said Steve. “I saw people as they were coming around the windows and around the garage door. I can remember seeing these people holding their hands up to the windows, looking in, trying to look for help.”

As they drew near, Sadie realized the passengers were calling out to her. “The people were saying, ‘Help me, help me, please.’ But they weren’t screaming, they weren’t yelling, they were quiet,” because the smoke they had inhaled made their voices hoarse. Some could barely speak. Later, she said, “a police officer asked me if I could estimate how many people I had seen. And I said I thought about 10 or 12, but everything was moving so fast, it just became a blur. They just kept coming.”

Alarmed but determined to do anything she could to help, Sadie threw open the storm door and ushered in a stream of dazed and disoriented men and women. Their hair was singed or burned away entirely, their faces and hands blackened. Hoping to provide the most basic form of first aid—water—she ran to the kitchen and turned on the faucet in the sink. She was dismayed to see nothing come out. She didn’t know it at the time, but the crash had cut off water and knocked out electricity to her house and most of her neighbors’ homes.

Desperate to do something, her next impulse was to phone for help. “I ran for the telephone to let somebody know what was going on, but there was no telephone service. Then I ran to the bathroom for water,” trying to help one badly burned man. “I don’t know why I did that. I think I was going to put him in the shower.” She reached for the knob and turned it, but no water came out of the showerhead. “In that minute,” she said, “I realized we didn’t have anything to help him.”

The smoke from the plane crash had surrounded the house and was engulfing her backyard, where she could see tongues of flame in the air through her back screen door. Frustrated at every turn, she now suddenly realized she had no idea where her children were and whether they were safe. “I ran to the basement to get them out,” she said.

All three boys, though, had already left the basement and wandered into the living room. “I knew something was wrong,” said Steve. “And I didn’t want to stay down in the basement. Curiosity got the best of me, and I wanted to make sure Mother was okay. As I got to the top of the steps, there was a large man. He was badly burned. And he looked me square in the eyes and said, ‘Help me.’ His voice was [almost] gone, but I could understand what he was saying. But at this point I was just literally petrified.”

Sadie found her sons mingling with the dazed survivors in the living room, but she had no idea that they had already been deeply frightened by the sight of others who had appeared at the basement windows to beg for help. They had also seen the man running toward the creek engulfed in flames. “I heard the baby [Eddie] saying, ‘Monster, mommy, monster,’” she said. She realized, she said, that “they had already seen too much.”

Now Sadie gathered her frightened boys together and herded them into the kitchen, where crash victims once again surrounded her. “They were asking me to help them. And I said, ‘You don’t understand, I have nothing to help you with.’”

Meanwhile, the Burkhalters’ front yard had been transformed into an inferno. Firefighters would have to extinguish the flames before emergency medical technicians could begin to look for more injured among the red-hot metal, the smoldering seats, and the bodies that lay everywhere—some of them burned beyond recognition, others tangled in electrical wires.

Even inside her home, Sadie could feel the intense heat radiating from the crash site. She became convinced that the house itself was in danger of catching fire—“With that kind of explosion and that fire, this house could flash. It could catch on fire really quickly”—and she was well aware that the people in her home needed to be taken to a hospital as soon as possible. Sadie decided that waiting for help to arrive was futile and that everyone in the house had to get out. She would lead the way out the back door, across the creek, and uphill to safety. “They didn’t understand how close we were to the plane. They didn’t know that those explosions were continuing. They were in such shock they just didn’t know. I guess they felt safe, and they needed somebody to help them. But I knew we had to get out of there."

Excerpted from Southern Storm: The Tragedy of Flight 242 by Samme Chittum published by Smithsonian Books.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.