What a Hundred-Year-Old Department Store Can Tell Us About the Overlap of Retail, Religion and Politics

The legacy left behind by the Philadelphia-based retail chain Wanamaker’s is still felt by shoppers today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/2b/b32b78f5-d79d-45df-8a65-54031b6c1c4b/gettyimages-128087440.jpg)

The story of large-scale, non-Amazon retail today is often one of frustration and failure, from Sears’s recent financial difficulties to the closure of Toys ‘R’ Us earlier this year. Abandoned big-box stores, department stores losing ground to online establishments and shopping malls falling out of fashion auger bleak financial implications for the communities where these spaces are located. It’s in sharp contrast to the often-extravagant stores run by the early pioneers of American retail—men like John Wanamaker, Marshall Field and Julius Rosenwald. Their stores blended extensive selections of goods for sale with public programs, art galleries and fine dining, and helped change what a nation thought “going to the store” could entail.

Even as the idea of a department store as a cultural destination has waned, echoes of the retail establishment’s heyday remain, from the ceremonial unveiling of holiday window decorations to celebrity appearances.

But there’s more to this story than simply the evolution of retail: from small shops to department stores to online retailers that mirror the selection of retail palaces without the physical space. Nicole C. Kirk’s new book Wanamaker’s Temple: The Business of Religion in an Iconic Department Store delves into how John Wanamaker’s religious and political beliefs shaped his retail empire, which at its peak included 16 stores around the mid-Atlantic region. At a point in time where retail and politics seem inexorably connected, the saga of Wanamaker offers numerous parallels to the ways we think about shopping today.

* * *

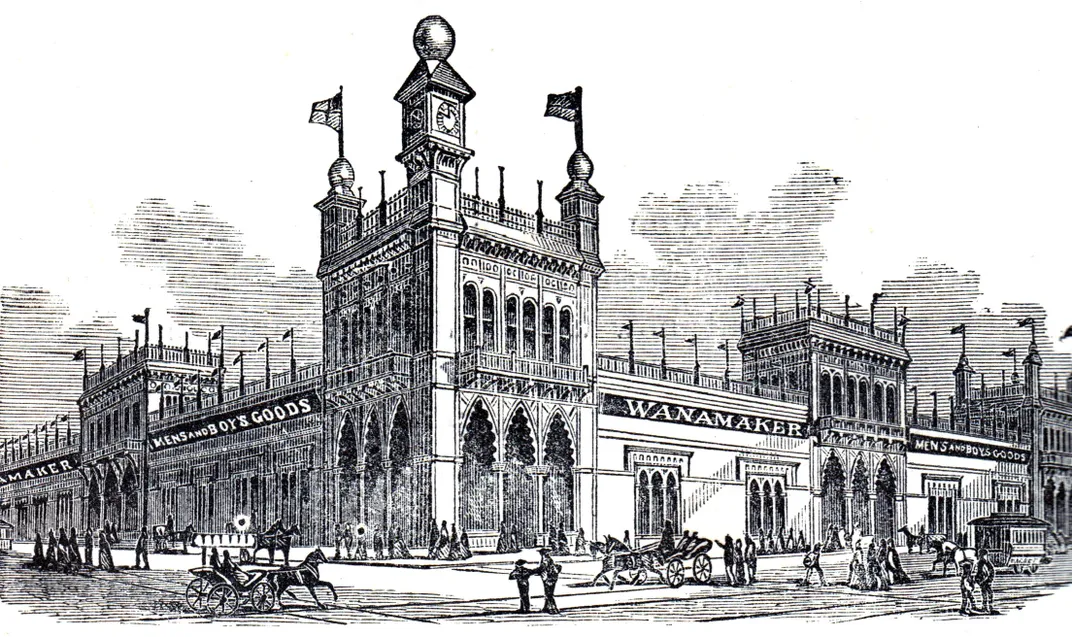

John Wanamaker was born into a family with a very different line of work than retail: Both his father and grandfather made bricks. As a young man, he worked in a dry goods store and later for Tower Hall, a Philadelphia clothing store. After saving up, he started his first business, focused on men’s clothing, with his brother-in-law; Wanamaker & Brown, Oak Hall opened in Philadelphia in 1861 on the eve of the Civil War.

For Kirk, the path to revisiting John Wanamaker’s history and legacy came through another book: Leigh Eric Schmidt’s 1995 Consumer Rites: The Buying and Selling of American Holidays. In it, she says, “[Schmidt] talks about the development of the public celebration of American holidays and their religious connections.” For Kirk, that sparked memories of department store holiday displays–and of the former Wanamaker’s location in Philadelphia’s Center City. Now a Macy’s, with some of its space having been turned into offices, the store still offers glimpses of its palatial splendor—as well as an organ that’s used for public programs.

Wanamaker’s helped to change the way Americans shopped. Before the advent of department stores, retailers were much more focused on specialty items—and much less focused on pleasing the customer. “In the old days, you had to know that you were going to go buy something, or you were kicked out of the store, and they treated you with suspicion,” Kirk says. “You had to haggle over prices. If you had a good relationship with the store owner, you would get a better price, and also there was a lot of bait and switch.”

Wanamaker's Temple: The Business of Religion in an Iconic Department Store

Remembered for his store’s extravagant holiday decorations and displays, Wanamaker built one of the largest retailing businesses in the world and helped to define the American retail shopping experience.

In her book, Kirk also discusses some of Wanamaker’s peers. Alexander Turney Stewart founded A.T. Stewart’s Emporium in New York City, which helped to establish the department store template with the Marble Palace, opened in 1848 as a women’s clothing store and the Iron Palace, which opened a decade lader, carried a wider selection of goods. By the 1870s, Kirk notes, Wanamaker’s stood alongside New York City's Macy’s and Boston’s Jordan Marsh as retailers that had “advanced from their dry goods and wholesale roots” successfully.

Kirk’s book describes Wanamaker’s 1871 visit to London, where he took in London’s Annual International Exhibition, which brought together art, commerce and technology. It was there, she notes, that he got the idea to expand the boundaries of what was possible for an American retailer to accomplish.

The business world had become too dishonest, too greedy and too eager to prey on the consumer, thought Wanamaker. Haggling over prices was a part of the practice, as was being suspicious of any customer just browsing the wares, rather than immediately making a purchase. Wanamaker was moved by his religion to change all that by infusing his establishment with what he saw as more moral, and therefore Christian, business practices. As a young man, he found religion when he heard singing coming from a First Independent Presbyterian Church and unwittingly arrived in the midst of a prayer meeting. At the church, he listened to a speech about morality, faith and business and became even more devoted to his religion, which he saw as working in tandem with his business acumen.

As Kirk writes, “Wanamaker understood himself as a moral reformer fueled by the desire to combat moral corruption.” The first Wanamaker’s was designed to evoke the interior of a vast church, was another way in which the store’s founder translated his Christianity into the retail experience.

Outside of the store, Wanamaker donated money to religious movements and organizations, like the nascent YMCA, as well as to Bethany Presbyterian Church. Kirk writes that Wanamaker wanted to “evangelize his consumers and employees, creating model middle-class Protestants.”

“One of the things that I found in the scholarship is that there's been a generation of scholars that doubted [his use of religious displays in the stores] as not sincere religious expressions,” Kirk said. “Certainly that's true for some, but I found that for Wanamaker, this was something he felt he was doing sincerely. Whether we judge that today or not is different, but he felt that this was a sincere blending of business and religion, and that he wanted to inspire with the message of Christianity and patriotism.”

Wanamaker held strong political ties—he served as Postmaster General in the Benjamin Harrison administration, and was active in local Republican Party politics—and the original Wanamaker’s abounded with patriotic details such as massive eagle statues.

At the dedication of Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, President William Howard Taft addressed the assembled crowd. Kirk notes in her book that “[i]t was the first time a sitting U.S. president took part in the dedication of a commercial enterprise.” KIrk notes that Wanamaker wasn’t the first to bring American politics and business together in this way–she cites Leland Stanford, governor of California in the 1860s, as a prime example of someone who would “align policy for the state to benefit business”–but he nonetheless played a significant role in breaking down the boundaries between the two, for better or for worse.

The company’s art collection, which was featured prominently in its flagship store, also derived from the store’s founder’s unique perspective on politics and religion. Kirk details the influence of Horace Bushnell’s A Christian Nurture and Augustine Duganne’s Art’s True Mission in America on Wanamaker’s thinking—notably, the idea that exposure to art could result in “a moralizing power.” In practice, this meant that Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia boasted an array of contemporary art comparable to—or greater than—numerous American museums of the time.

Kirk notes that it didn’t hurt that Wanamaker’s department store was more centrally located in Philadelphia than the original location of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was situated in Fairmount Park. “You go to see the art, and then suddenly you say, ‘Oh, we need to buy another set of gloves,’” says Kirk.

But viewing this art collection as a precursor to, say, Amazon Prime Video serving as a loss leader for the company wouldn’t be accurate, Kirk says. “I feel it's truly an attempt at an aesthetic evangelism, and that he felt that these surroundings would inspire the right religious feelings,” said Kirk. “This is following [art critic John] Ruskin and others of the time who were also espousing this perspective.”

Wanamaker’s art collection included Pierre Fritel’s then-controversial painting Les conquérants. Fritel is a more obscure artistic figure now, but at the time of the painting’s completion in 1892, it caused a stir with its depiction of historical conquerors like Julius Caesar, Charlemagne and Genghis Khan walking on horseback through a field of corpses. Wanamaker purchased the painting in 1899 to display in his store; in 1905, visitors to the store received a booklet containing an essay explaining the painting in political and theological terms, addressing the complexity of human ambition and the dreadful power of greed. This was not the only instance of Wanamaker engaging in cultural publishing: A booklet released to commemorate the store’s grand organ featured an essay by lauded French writer Honoré de Balzac, who wrote, “The chanting of a choir in response to the thunder of the organ, a veil is woven for God.”

* * *

The influence of John Wanamaker’s views on religion and retail continue to be felt today. Numerous American companies use their retail presence as a way of evangelizing their customers, including department store Forever 21 and fast food chain Whataburger.

John Wanamaker, Kirk noted, was “one of the early adherents to what we call now the prosperity gospel. He believes that as his business grows bigger and it's doing better, [that] these are all God's blessings.” For him, this went hand-in-hand with what Kirk called “an amazing array of moral reform movements,” such as his work with the Philadelphia YMCA and the Bethany Sunday school, which he contributed to both organizationally and financially. He also allowed revivalists Dwight L. Moody and Ira D. Sankey to use the site of a future store for a massive revival in 1875. “He was on a dizzying amount of boards,” Kirk said; later, she added that “he certainly must've not slept much.”

Wanamaker often put his personal beliefs ahead of his business interests. “He's making conscious decision about being closed on Sunday, even though it lost a lot of profit,” Kirk said.” He made a conscious decision not to serve alcohol in his restaurants, which he's losing out in revenue.”

When asked for a more contemporary figure who approximated Wanamaker’s blend of business savvy, and religious and political convictions, Kirk quickly named Walmart founder Sam Walton. “In their own understanding of their politics and their religious outlook, that there's certainly a lot of similarities,” she said.

Kirk also found parallels between Walmart’s effect on the retail landscape and Wanamaker’s refinement of the department store. “Walmart changed the American landscape, and depending on where you are, you think it's wondrous, or you think it's absolutely devastating,” she said. “The same was said of department stores.”

As the world of retail continues to evolve, it will be influenced in ways both subtle and grand by the beliefs of those operating these businesses. Some will bring their own idiosyncratic views to bear on the everyday lives of these establishments; as we ponder their effects on the larger society, the complex legacy of John Wanamaker offers a glimpse into how these views can play out on a grander scale.

Editor's Note, February 12, 2019: An earlier version of this story contained a photo caption that misidentified the location of Wanamaker's on Philadelphia's Market Street.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.