What This Jacket Tells Us About the Degrading Treatment of Japanese-Americans During WWII

An exhibit in San Francisco explores the dark chapter in American history when the government imprisoned its own citizens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/22/6f2286c8-d5da-4778-9325-d43eaa75db0d/tnen_they_came_for_us_-0035.jpg)

Question 28: “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States... and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?”

Such was one of the many accusatory questions directed at Japanese-American citizens by the U.S. government during World War II. Itaru and Shizuko Ina faced them in 1943, when at an internment camp in Topaz, Utah, they refused to swear their loyalty to the United States, their native country, answering no to that question and another about serving in the U.S. military.

Horrified at what was happening in the United States, the Inas decided to renounce their American citizenship, risking being without the protection of any nation-state. Until that moment they had been proud Americans, according to their daughter, Satsuki, but the Inas chose to defy the authorities rather than continue raising their children in a country so hostile to the Japanese.

Itaru Ina was born in San Francisco, and after going back to Japan with his sister who was ill, he returned to the United States as a teenager. He was working as a bookkeeper and studied poetry and the bamboo flute when he met Shizuko, who was also American-born, at the Golden Gate International Exposition, where she was representing a Japanese silk company.

Before the outbreak of World War II, the Inas enjoyed their life in the United States, but once the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, hysteria and anti-Japanese prejudice led to President Franklin D. Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066. Signed in February 1942, two months after the U.S. entry to the war, the order forced Japanese-Americans to leave their homes, businesses and belongings, taking only what they could carry to imprisonment camps where they would spend the duration of the war.

Upon refusing to swear allegiance to the United States, Itaru and Shizuko, along with their infant son were sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a maximum-security camp in California ringed by three strands of barbed wire and 24 guard towers. Itaru continued his protest of his treatment and that of his fellow Americans, insisting that they should resist being drafted into the Army unless their constitutional rights were restored. The War Relocation Authority then sent him to a prison camp in Bismarck, North Dakota—leaving his family behind—where he was given a jacket with the initials “E.A,” for “enemy alien,” on the back inside a broken circle.

Today, the dark, blue denim jacket hangs in a display at an exhibit at San Francisco’s Presidio, Then They Came For Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII and the Demise of Civil Liberties, an exhibit that tells the broader story of the wartime imprisonment of Japanese-Americans on the West Coast.

“[My dad] was assigned this jacket, and it’s like new because he refused to wear it,” says Satsuki Ina, a 74-year old psychotherapist who loaned the article of clothing for the exhibit. “They told him the circle around the E.A. would be used as a target if he tried to escape.”

Upon the issuance of Roosevelt’s executive order, 120,000 Japanese-Americans, two-thirds of them born in the U.S., were given just a week or so to settle their personal affairs and businesses. The federal government, under the supervision of the U.S. Army, arranged assembly centers—often former horse stalls or cow sheds— before assigning the incarcerated to one of ten camps, called relocation centers. The typical facility included some form of barracks, where several families lived together, and communal eating areas. They were built sloppily, often out of green wood, which would shrink so dust and wind seeped through the cracks. During the day, some internees would work at the camps, making maybe $13 a month. Students attended hastily constructed schools; the government had no real long-term plan for what would happen to people, and no real oversight was established. Harsh weather made life at the camps even more intolerable.

“Dust storms were the bane of people’s existence in the desert,” says Anthony Hirschel, the curator of the exhibition. “It was very rough.”

While the exhibit came to San Francisco by way of earlier showings in New York and Chicago, the Presidio holds extra significance—in the 1940s it served as the Western Defense Command, the military base that oversaw the implementation of Japanese-American imprisonment.

The Presidio’s exhibit is also the only one to tell the story of the Inas, as each exhibition has tried to work with local people and groups affected. For her part, Satsuki says she wouldn’t want her father’s jacket to ever leave California.

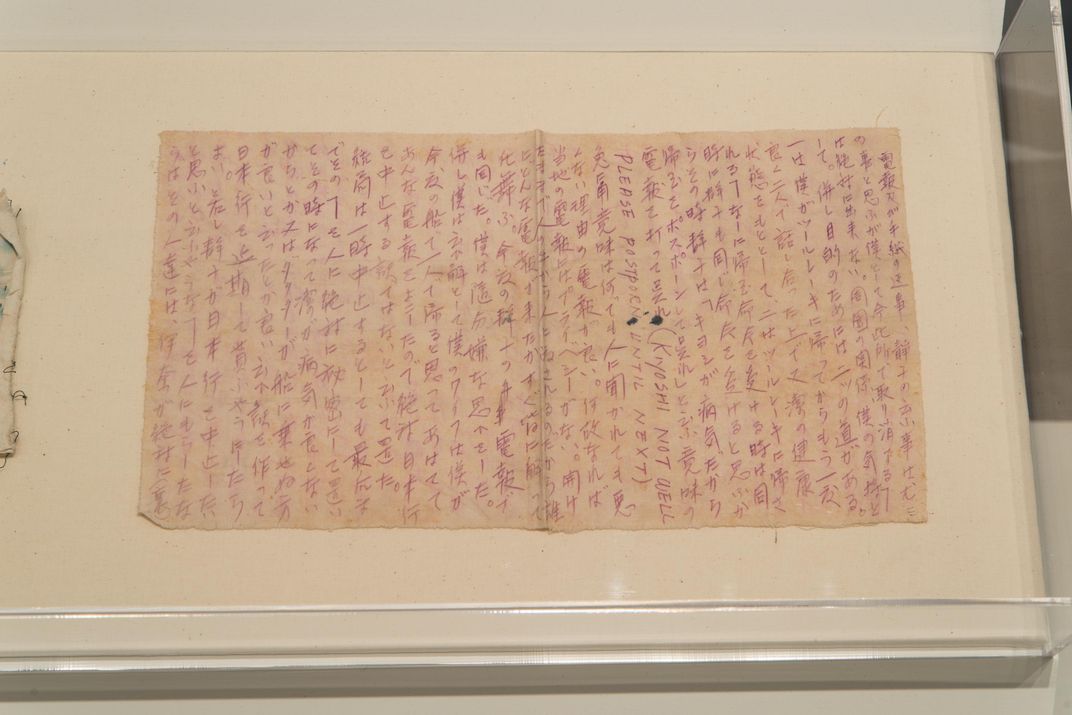

Along with the jacket, Satsuki loaned a toy tank her father built for her brother, Kiyoshi, with scraps of wood, using thread spools and checkers for the wheels. The exhibition also includes a letter Itaru wrote to Shizuko addressing her concerns about going back to Japan after the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To avoid the censors, Itaru wrote it on a piece of his bedsheet that he then concealed in his pants with a note of misdirection asking his wife to mend them for him.

Ina sees her father’s objects as part of the little-known story of resistance to the internment.

“They were all forms of protest,” she says. “They both answered no on the loyalty questionnaire, and they felt in despair. Then he refused to wear the jacket as a form of protest because his constitutional rights had been abandoned.”

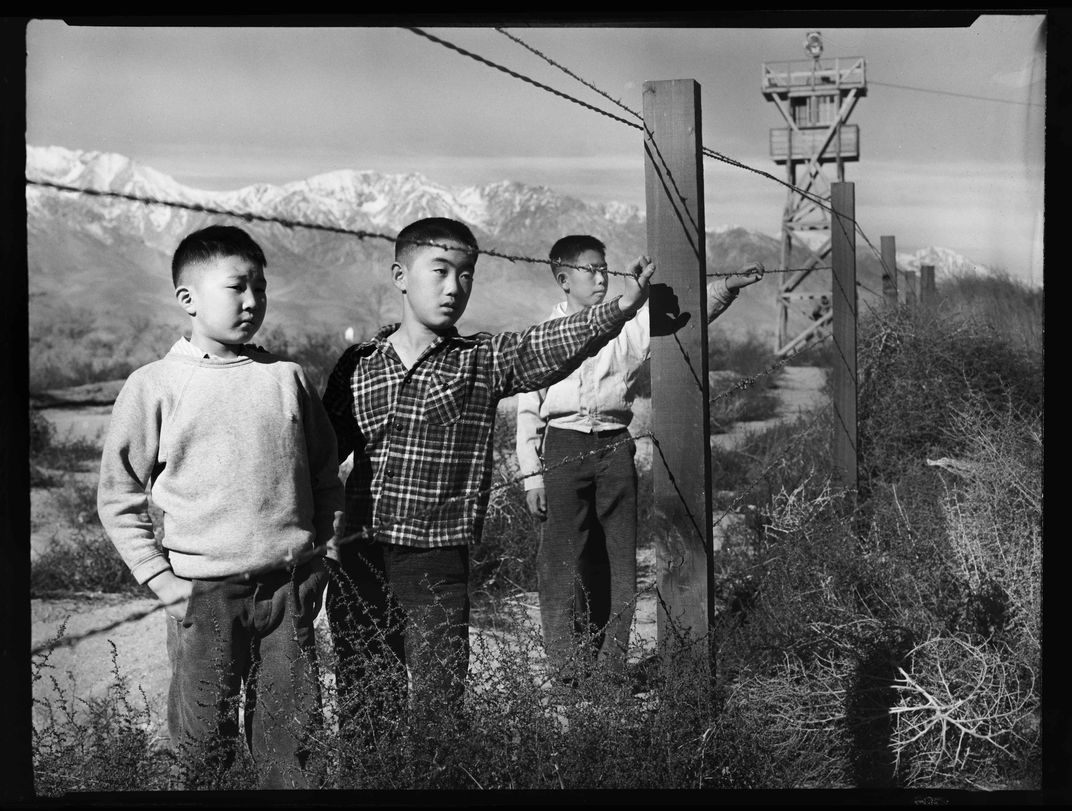

The exhibit displays photos by noted American photographer Dorothea Lange, who was commissioned by the government to document the camps but were hidden from the public for decades, along with works by incarcerated Japanese-American artists that document eviction, daily life in the incarceration camps, and returns to home.

Before the war, the vast majority of Japanese-Americans lived on the West Coast, and the exhibit also touches upon what happened to those who returned to northern California after interment.

“Some of them wound up in government housing, some found their belongings intact, but for some of them, the places where they’d stored their belongings had been vandalized,” says Hirschel. “Sometimes other people preserved their businesses for them and agreed to keep working on their farms while they were gone.”

Hirschel recalls a photo in the exhibit of the Nakamura Brothers, who were fortunate to have a local banker pay their mortgage while they were imprisoned. “It’s never just black-and-white, and there were certainly people who spoke up.”

Artifacts like those on display in the exhibit, including those loaned by the Ina family, make a difference, says Karen Korematsu, whose father Fred was convicted for refusing to evacuate. His criminal case went to the Supreme Court where the justices infamously ruled in favor of the government, 6-3, writing that the detention was a “military necessity” not based on race.

Karen Korematsu now runs the Fred T. Korematsu Institute, a civil rights organization focused on educating Americans on the tragedies of internment so that they might not repeat them.

“[Artifacts] are personal and they’re tangible,” she says. “That’s how people learn – by personal stories.”

Ina is currently working on a book about her family, with her perspective woven together with the letters her parents wrote to each other, as well as her father’s haiku journal and the diary her mother kept. Satsuki says her parents’ defiant acts were made without knowing what would happen to them. When they left the camps, the internees were given $25 and a bus ticket.

After they were released, the Inas lived in Cincinnati, where they had some family, and then returned to San Francisco. Her father went back to his job as a bookkeeper at an import/export company, but he didn’t make enough money, so they started a window-design business.

It’s important that the story of the Japanese incarceration reaches a broad audience, Korematsu says.

“Anti-Muslim rhetoric and racism is so prevalent now,” she said. ”When I talk about my father and what he represents, I focus on using good to fight the evil. This is not just a Japanese-American story or a West Coast story – this is an American story.”