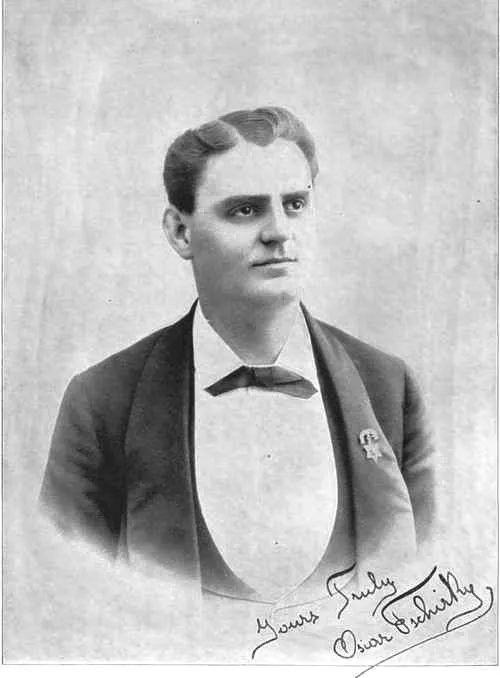

What Made Oscar Tschirky the King of Gilded Age New York

During his long tenure as maître d’ at the famed Waldorf Hotel, Oscar had the city’s elite at his fingertips

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/4e/394e5ada-a90a-4459-91a0-fbeffb8b1e7b/nypldigitalcollections6cf030e0-48e1-0132-e0b0-58d385a7b928001w.jpg)

At 6 a.m. on March 13, 1893, a 26-year-old Swiss immigrant approached the doors of the Waldorf Hotel in mid-town New York City and turned the key, opening the grand building to the public for the first time. Surrounded by clerks and elevator boys, he waited a full minute for the arrival of the first guest, a representative of William Waldorf Astor, who had razed his own Fifth Avenue home to erect the 450-room hotel but lived in London and seldom visited. From the moment the doors were unlocked, however, it was Oscar Tschirky, the longtime maître d’, who made the place tick.

On the very next night, Oscar hosted an elaborate charity ball at the Waldorf for 1,500 with the New York Symphony. He soon greeted a Spanish duke, Punjabi maharaja, and the President of the United States. Widely known only by his first name, Oscar planned nine-course dinner menus and graciously answered thank-you notes. When guests returned to Europe by steamer, he sent grapefruits to their cabins.

It was a heady atmosphere for a young man from La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, a remote medieval town in the Jura Mountains. There, artisans had wound clocks for centuries; in New York, men talked of steel, railroads and electricity. Having once lived on a farm, Oscar was now surrounded by silk tapestries and Baccarat crystal. In both places, though, it helped to speak German and French; at the Waldorf, a composer from Berlin or a diplomat from Paris was immediately understood.

Unlike other hotels at the time, the Waldorf was not just a place for travelers to rest, but for locals to mingle. Wealthy, young New Yorkers, tired of their parents’ formal rituals and claustrophobic parlors, were lured out of private homes to entertain in public. The Waldorf gave them the same attentiveness that they received from hired help in their own dining rooms. Social climbing became a spectator sport. In the hotel corridors, leather settees encouraged gawking, while the storied Palm Room restaurant’s glass walls ensured that diners remained on display. As one contemporary quipped, the Waldorf brought “exclusiveness to the masses.” Anyone with money was welcome.

Oscar was the hotel’s public face, as essential to the atmosphere as the inlaid mahogany. New York had 1,368 millionaires; he learned their names. Such personal service, ever rare, became the hotel’s most valuable asset. It’s why J. Pierpont Morgan was a regular—only Oscar could serve him—and international dignitaries booked rooms. In his 50 years at the Waldorf, Oscar waited on every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to FDR and was awarded medals from three foreign governments. In an increasingly populous and anonymous city, Oscar understood that everyone wanted to be known.

Ten years prior to the Waldorf’s opening, Oscar and his mother had stepped off a transatlantic ship themselves. They took a horse-drawn cab up Broadway, which was strung with flags to celebrate the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, and glimpsed telegraph poles, flower shops and elevated trains. As Oscar described it decades later in Karl Schriftgiesser’s 1943 biography Oscar of the Waldorf, his older brother, a hotel cook, was living on Third Avenue; Oscar dropped his bags at the apartment and went out to find a job. Within a day, he was working as a busboy at the Hoffman House, clearing empty glasses of sherry cobbler at tables of Manhattan’s elite.

Oscar learned to be clean, attentive, and sincere. Guests warmed to his modesty and wide, kind face. An amateur weight lifter and bicycle racer, he had a sturdy build that projected discipline. Early on, the owner of the Hoffman House, Ned Stokes, tapped Oscar to work Sundays on his yacht, telling him to keep any cash left over from poker games. But when he found a spare $50 on the table, Oscar balked at accepting such a prodigious tip. Stokes, an infamous oil man, laughed and told him to clear it up.

By the time he heard about the opulent hotel going up on Fifth Avenue, Oscar was in charge of the private dining rooms at Delmonico’s, the city’s best restaurant, and was ready for a change. Astor’s cousin, a regular there, put Oscar in touch with the Waldorf’s general manager, George Boldt. Oscar showed up to the interview with a stack of testimonials from prominent New Yorkers (including industrialist John Mackay, crooked financier “Diamond Jim” Brady and the actress Lillian Russell.) He started in January 1893 at salary of $250 a month—about $6,000 today—and buried himself in the unglamorous details of ordering silverware and hiring staff.

The Waldorf cost $4 million to build and grossed that much in just its first year. Its 13 brick-and-brownstone stories were a German Renaissance confection of spires, gables and balconies. In 1897, it was joined by a sister property, the Astoria, located next door, making it the largest hotel in the world, but it was torn down in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building. (A new Waldorf-Astoria was built uptown on Park Avenue in the 1930s.)

The original Waldorf, with Oscar as its public face, opened on the eve of a depression and specialized in tone-deaf displays of wealth. While impoverished New Yorkers formed bread lines downtown, financiers smoked in an oak-paneled café modeled on a German castle. The ladies’ drawing room, apparently without irony, reproduced Marie Antoinette’s apartment. Irresistibly ostentatious, it became the de facto headquarters of the late Gilded Age.

Most evenings, Oscar greeted guests outside the Palm Room and, based on their social standing, decided whether there was, in fact, a spare table for dinner. He stood with a hand on the velvet rope, something he invented to manage crowds but which only heightened the restaurant’s popularity. “It seemed that when people learned they were being held out,” he recalled years later, “they were all the more insistent upon getting in.” His smile of recognition was currency: It meant that you belonged.

Yet Oscar was by nature more a gracious host than social arbiter. He made “both the great and the not-so-great feel at ease,” according to the Herald Tribune. When, with much fanfare, the Chinese diplomat Li Hung Chang visited the Waldorf, he took a liking to Oscar and asked to meet his sons. A reporter observed that “Oscar and his two little boys were the only people in New York who made the Viceroy smile.”

Oscar’s large, dark eyes looked on all guests with warmth and concern. Thoughtful gestures fill the pages of his correspondence, held in the archives at the New York Public Library.

If an acquaintance took ill, he sent a note and jar of jelly. If he found a request excessive—ceremonial doves, custom ice-cream boxes, or a parade of model battleships for a party—he never let on. Bringing dignity to a brash age, Oscar gingerly managed Western land speculators and played confidante to their wives. While he was at it, he subtly schooled Americans in fine European dining.

It all paid very well and made him famous. By 1910, Oscar was making $25,000 a year and held shares in the hotel. He and his wife owned a house on Lexington Avenue and a 1,000-acre farm upstate. Though never a chef, he devised simple recipes like the Waldorf salad, originally a combination of only apples, celery, and good mayonnaise, according to his 1896 cookbook. Its publication created a lifelong misconception that Oscar himself was at ease in the kitchen, when in fact he could barely scramble an egg.

As Oscar’s reputation spread nationwide, journalists mined him for advice on everything from Christmas menus (he suggested oysters, smelts, roast turkey, and mince pie) to the secret of a long life (a cocktail, well-shaken). In a typically breathless character sketch, the Baltimore Sun called him “an epicurean Napoleon” who was “the consulted in all emergencies, the friend and counselor of more people…than any other man in the city.” Even his trifling comments made headlines. When reporters gathered in his office in 1933 for his 70th birthday, Oscar admitted that his favorite meal was a simple plate of boiled beef and potatoes; the New York Times ran a story titled, “Oscar of Waldorf, 70, Hails Plebian Dish.”

In 1941, two years before he would retire, Oscar threw a luncheon that was more to his taste than the grand Waldorf banquets. He served pea soup, spring chicken, and string beans. Everything, even the fruit in the applejack, was grown on his New Paltz estate, which he was transferring to the Société Culinaire Philanthropique, a hospitality trade association. It would become a retreat and retirement community for chefs. Today, with the original Waldorf-Astoria long gone and the second iteration slated to be converted into condominiums, the Culinarians’ Home still exists, welcoming guests just as Oscar did more than a century ago.