What the New Cesar Chavez Film Gets Wrong About the Labor Activist

Despite the good intentions, the biopic misleads and distorts his role in the farm workers movement

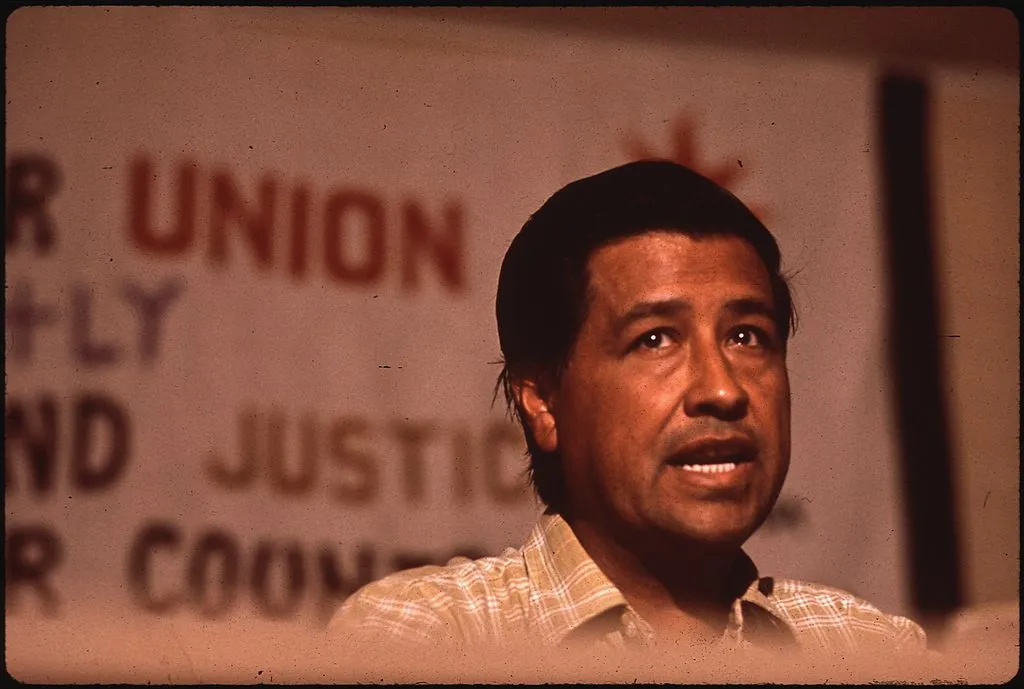

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/5f/135f5d13-d3c4-411b-bd34-130f6a96ccf9/cesar_chavez_by_matt_garcia.jpeg)

Most great men have one. Malcolm X has one. Gandhi has one. Mandela got one last year. And now, Cesar Chavez has his.

The biographical film or “biopic”—like Cesar Chavez, which came out this past weekend—lends itself to the creation of legends. In the case of Chavez, the legend is complicated by the fact that his story did not exactly lead to the liberation of the people he represented. Great strides were made during the heyday of the farm workers movement—namely the first contracts for farm workers and a California law that recognized their right to unionize. But field workers today suffer indignities familiar to those who worked in rural California prior to Chavez starting a union in 1962.

These facts are not the concern of Diego Luna, the Mexican niño prodigio turned director of the new film. In a recent appearance at UCLA, Luna told his audience, "We have to send a message to the [film] industry that our stories have to be represented. And with the depth and the complexity they deserve."

Fair enough. As a Mexican American and a historian, I too long for dignified cinematic portrayals of Latinos—if for no other reason than to impart histories to my students that convey the struggles for equality our people have initiated. College professors can only show John Sayles’ terrific 1996 film Lone Star, about a Texas border town, so many times. 2011’s A Better Life, about an undocumented gardener in Los Angeles, is a welcome but all too rare addition to the genre.

My yearnings, however, should not come at the expense of historical accuracy, as they do in Cesar Chavez. Having recently published a book on the United Farm Workers and Chavez, I could easily get very particular about the details. (Pointing out, for example, that Luna situates the 1973 picket-line murder of farm worker Juan de la Cruz prior to 1970.)

But in the new film, Luna’s omissions and alterations are really historical subversions and go well beyond the poetic license we should permit filmmakers. His interpretation, I suspect, is a product of his unsophisticated handling of U.S. identity politics. He rejects the multiethnic community that made up the farm workers movement in favor of a simplistic notion that Mexicans did all the work. Creating a hero comes at the expense of depicting an entire social movement.

The Filipino American National Historical Society has rightly come out against the film’s misrepresentation of labor leader Larry Itliong, and the erasure of others such as Philip Vera Cruz and Pete Velasco. They’ve also questioned Luna’s failure to acknowledge the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee--an organization made up largely of Filipinos--which initiated the 1965 grape strike. The strike functions as a turning point for the union’s formation in the film.

Similarly, any mention of white volunteers and organizers beyond Fred Ross, Cesar’s mentor, and Jerry Cohen, the talented leader of the UFW legal team, is absent. Several white ministers and students played a critical role in launching and sustaining the movement, including Reverend Jim Drake, who came up with the winning strategy of the boycott, not Chavez. As the film lumbers toward the epic signing of the first contracts in 1970, Luna’s most egregious distortion of history comes when he shows Chavez boarding a ship to London. In the film, the labor leader walks the wharf on the Thames River, lobbies dockworkers not to unload grapes, and appeals to consumers not to buy the fruit. Although this work actually happened, it was a young Jewish American volunteer, Elaine Elinson, who almost singlehandedly convinced the British and Scandinavian unions to keep the grapes out of Europe.

The film even fails to represent accurately the supporting cast of Mexican American activists in Cesar’s orbit. Gilbert Padilla, played by Yancey Arias, and Dolores Huerta, played by Rosario Dawson, come off as nothing more than a yes-man and yes-woman to Chavez when, in fact, they were distinguished organizers in their own right and effective innovators of new strategies, including the boycott. Only Helen Chavez, Cesar’s wife, is presented as a character with her own mind and story, a tribute to America Ferrera’s standout performance.

But the film probably does the greatest disservice to Cesar Chavez himself. The director opts out of the 1970s altogether, a period in which Chavez struggled with personal and professional demons, lost interest in organizing farm workers, and became invested in creating a community rather than solidifying gains made in the previous decade. Such a storyline would have done little to burnish his credentials as a civil and labor rights leader, but it would have made for a more dramatic and compelling film. More importantly, it would have made for a much more accurate portrait of the depth and complexity of the real man.These omissions reflect the limitations of the genre and the hero-making project of this film in particular. With rare exception, biopics elide complexity and avoid overt criticism of their subjects. This is why the most extraordinary and entertaining renditions of historical figures have often come via fictionalized characters, whether it be Orson Welles’ Charles Foster Kane based on William Randolph Hearst (Citizen Kane), Roman Polanski’s Noah Cross based on William Mulholland (Chinatown), or P. T. Anderson’s Daniel Plainview based on Edward Doheny (There Will Be Blood).

In fairness to Luna, Chavez was delivered to him with decades of historical baggage, thanks to hagiography and political stamps of approval from Robert Kennedy, Jerry Brown, and most recently, Barack Obama. Although new histories are now being written, including Miriam Pawel’s impressive biography, The Crusades of Cesar Chavez, it will take time for the public’s perception of the hero to catch up with the all-too-human Chavez. Sadly, Luna’s film does almost nothing to assist this move toward a new understanding of Cesar Chavez’s life and the successes and failures of the movement he led.

Matt Garcia is the director of the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University. His most recent book, From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement (University of California Press), won the Philip Taft Award for the Best Book in Labor History, 2013. He wrote this for Zocalo Public Square.