What Reviewers Said About the First Mac When It Debuted

They nitpicked the hardware, but reviewers appreciated the groundbreaking features that would redefine the personal computer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/82/c5820ed7-0a81-4b80-9b0b-f1b162b36fde/mac_1a.jpg)

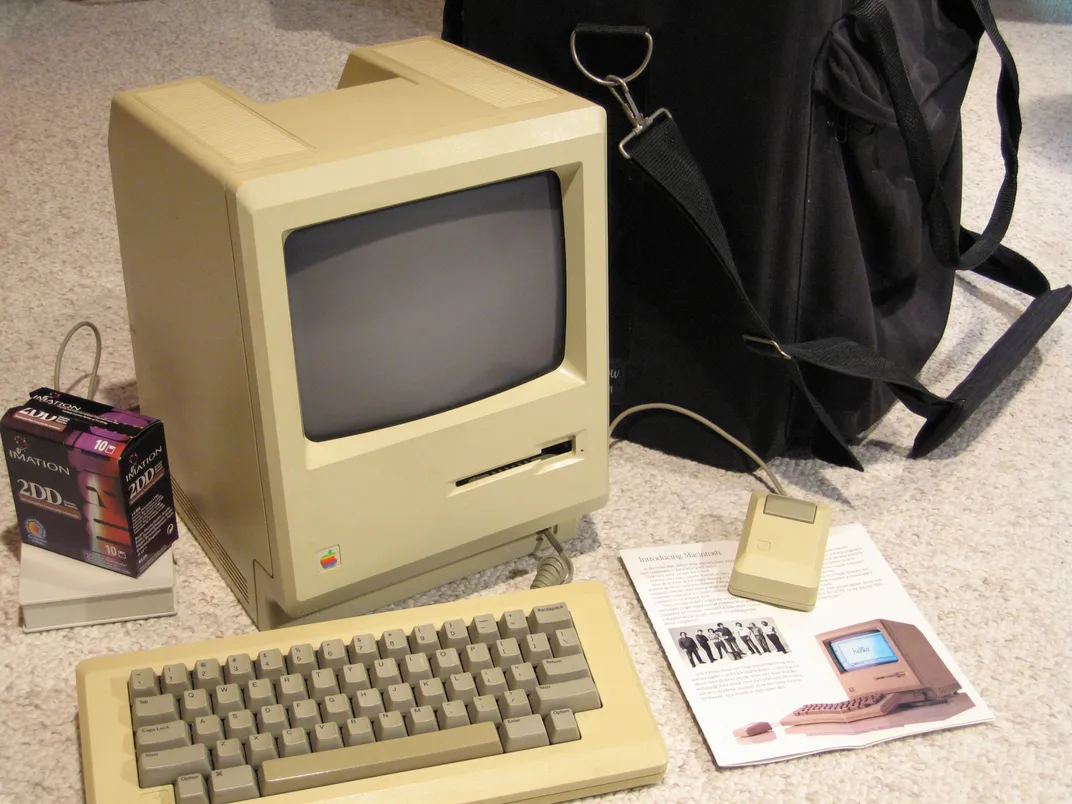

On January 24, 1984, a 28-year-old Steve Jobs appeared onstage in a tuxedo to introduce a new Apple computer that had been in the works for years: the Macintosh.

Two days earlier, during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII, Apple aired a commercial that brought already-high expectations for the Mac to a fever pitch. In the ad, a nameless heroine runs through a dystopian setting, where a face projected onto an enormous screen commands a room full of conformists to obey. Evading police in riot gear, the heroine smashes the screen with a giant hammer, freeing the audience. The message: IBM was 1984's Big Brother, and Mac was the audacious liberator.

Up on stage, after unzipping the 17-pound computer from a carrying case, plugging it in and turning it on, Jobs showed a feverishly cheering audience screenshots of killer applications like MacWrite and MacPaint. The device—designed around a user-friendly graphical user interface and mouse that debuted in the previous Lisa computer—was remarkably intuitive for non-experts, allowing them to use the mouse to select programs they wanted to run, rather than type in code.

On the whole, reviewers seem to have been impressed by the the features of the $2,495 machine. But when the New York Times' Erik Sandberg-Diment first sat down at the computer, he was less than thrilled with the screen size:

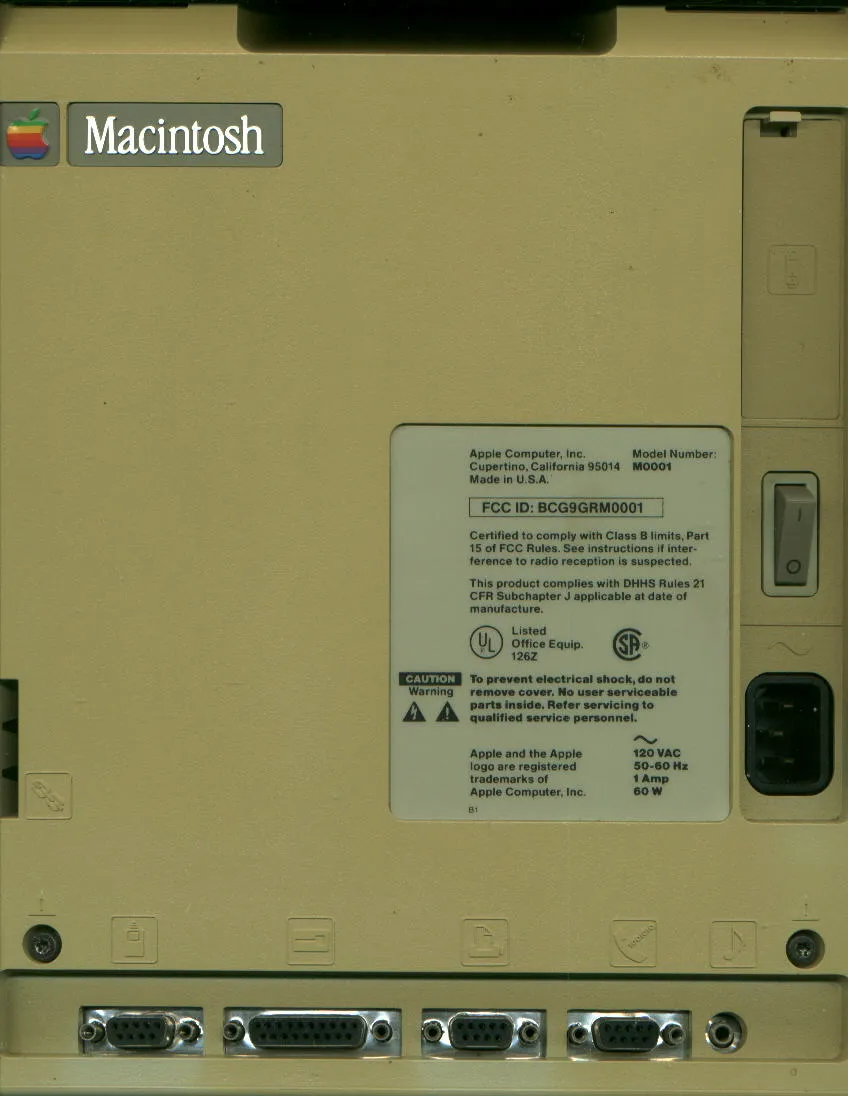

The first thing to take me by surprise as I sat down at the Macintosh was not the mouse pointer used to move the cursor on screen, which everyone has been expecting, but the size of the screen itself. With a scant nine-inch diagonal, it presents a diminutive five-by-seven viewing image. My personal dislike for small screens made me chalk up an immediate minus on the Mac's scorecard.

At the time, the Mac's main rival for the home user market was the IBM PCjr, which had a 14-inch monitor and cost $1,269. Sandberg-Diment also nitpicked other aspects of the Mac's hardware: the keyboard didn't include a number pad, and the screen was black-and-white.

To his credit, though, he appreciated that these concerns were dwarfed by the computer's unprecedented graphic resolution, intuitive operating system and innovative mouse. A smaller monitor didn't matter because the computer was so much easier to use.

"The Mac display makes all the other personal computer screens look like distorted rejects from a Cubist art school," he wrote. "The fundamental difference between the Mac and other personal computers is that the Macintosh is visually oriented rather than word oriented."

In a glowing review for the Los Angeles Times, Larry Magid expressed amazement over many of the metaphor and skeuomorphic features that would come to define the personal computer, surrounded by quotation marks that are remarkably quaint today.

"Once you've set up your machine, you insert the main system disk, turn on the power, and in a minute you are presented with the introductory screen. Apple calls it your 'desk top'. What you see on your screen looks a lot like what you might find on a desk," he wrote.

His analysis of the user-friendly visual interface—which was quickly copied by Microsoft and soon spread to virtually every personal computer—sounds strikingly like the awe we expressed after first seeing the iPhone's intutitive touch screen-controlled operating system in 2007.

"It uses a hand-held 'mouse'—a small pointing device which enables the user to select programs, and move data from one part of the screen to another," Magrid wrote. "When this process was described to me, it sounded cumbersome, especially since I'm already comfortable with using a keyboard. But the mouse is so much more intuitive. As infants we learned to move objects around our play pens. Using a mouse is an extension of that skill."

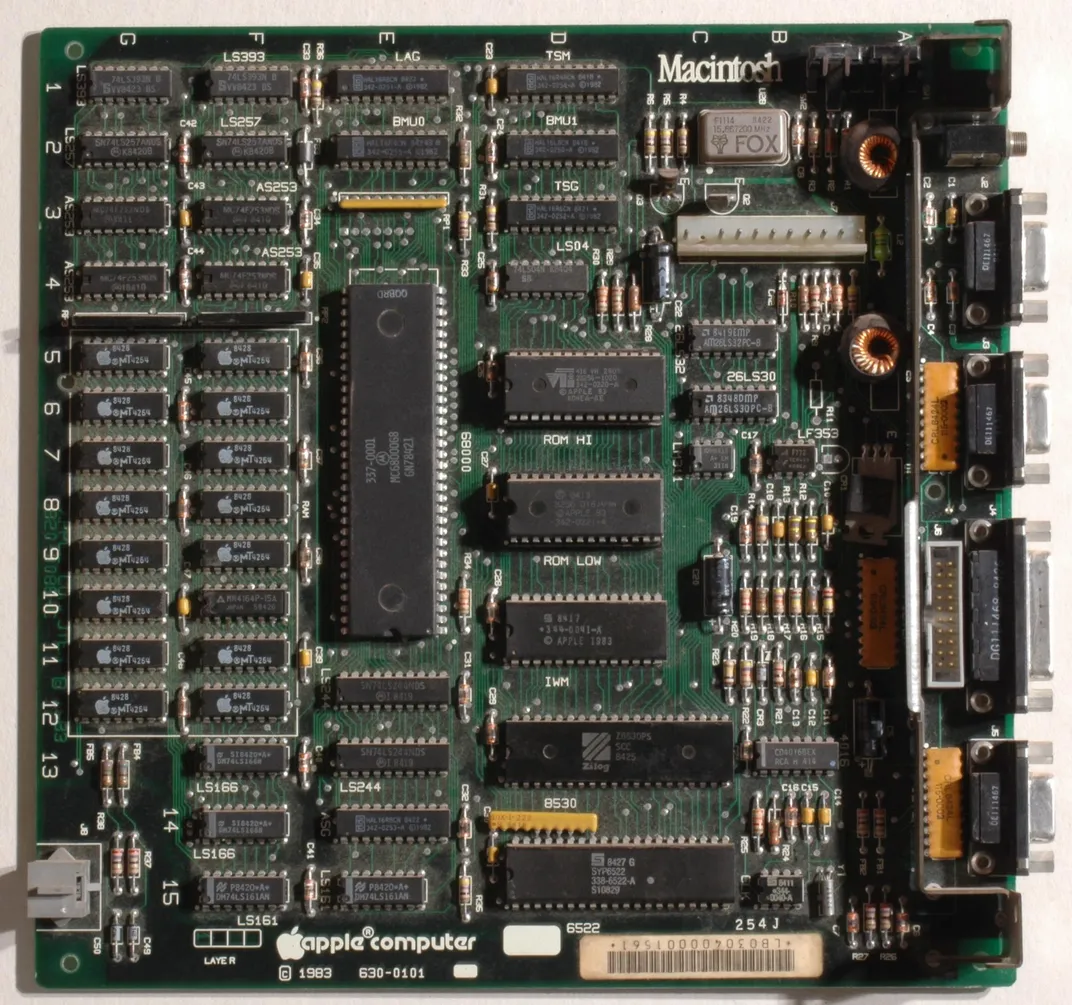

Writing in Byte, Gregg Williams comprehensively broke down the machine's specs and groundbreaking capabilities—and made a prediction about the Mac's future that was prescient, but also mistaken. "It will be imitated but not copied," he wrote. "To some people, Apple will be as synonymous with the phrase 'personal computer' as IBM is snynonymous with 'computer.'"

Williams was correct in anticipating how profoundly the Mac's features would appeal to the casual computer user. But he was wrong in that those capabilities wouldn't be thoroughly copied by Microsoft Windows, which could run on IBM and virtually every other brand of computer besides Mac. Eventually, in fact, Windows computers so thoroughly dominated the home user market that Williams' prediction was inverted: Windows became synonymous with PC, the exact opposite of Mac.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/cb/c7cbec6c-89cd-45c6-b1c8-fb8b9db57a30/mac_4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)