What the Six-Day War Tells Us About the Cold War

In 1967, Israel launched a preemptive attack on Egypt. The fight was spurred in part by Soviet meddling

:focal(530x576:531x577)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/52/dc523a26-fa96-49a0-ab1d-c630711016cd/ap_06071407004_copy.jpg)

In the 70 years since the United Nations General Assembly approved a plan to divide British Palestine in two—a Jewish state and an Arab one—the region of modern-day Israel has been repeatedly beset by violence. Israel has fought one battle after another, clinging to survival in the decades after its people were systematically murdered during the Holocaust. But the story of self-determination and Arab-Israeli conflicts spills out far beyond the borders of the Middle East. Israel wasn’t just the site of regional disputes—it was a Cold War satellite, wrapped up in the interests of the Soviets and the Americans.

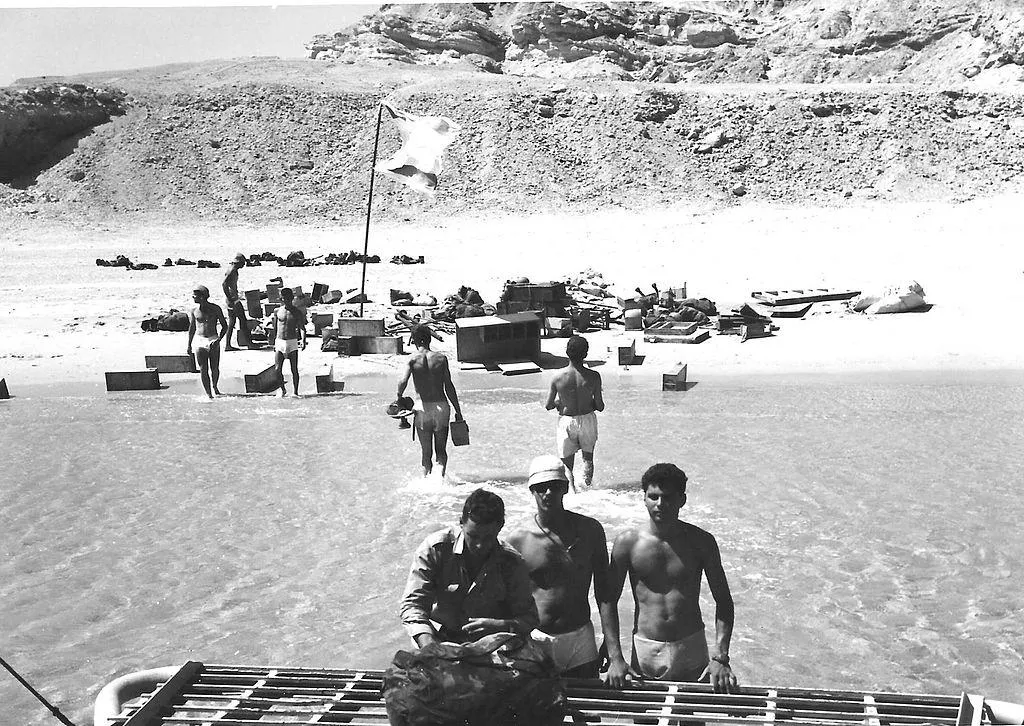

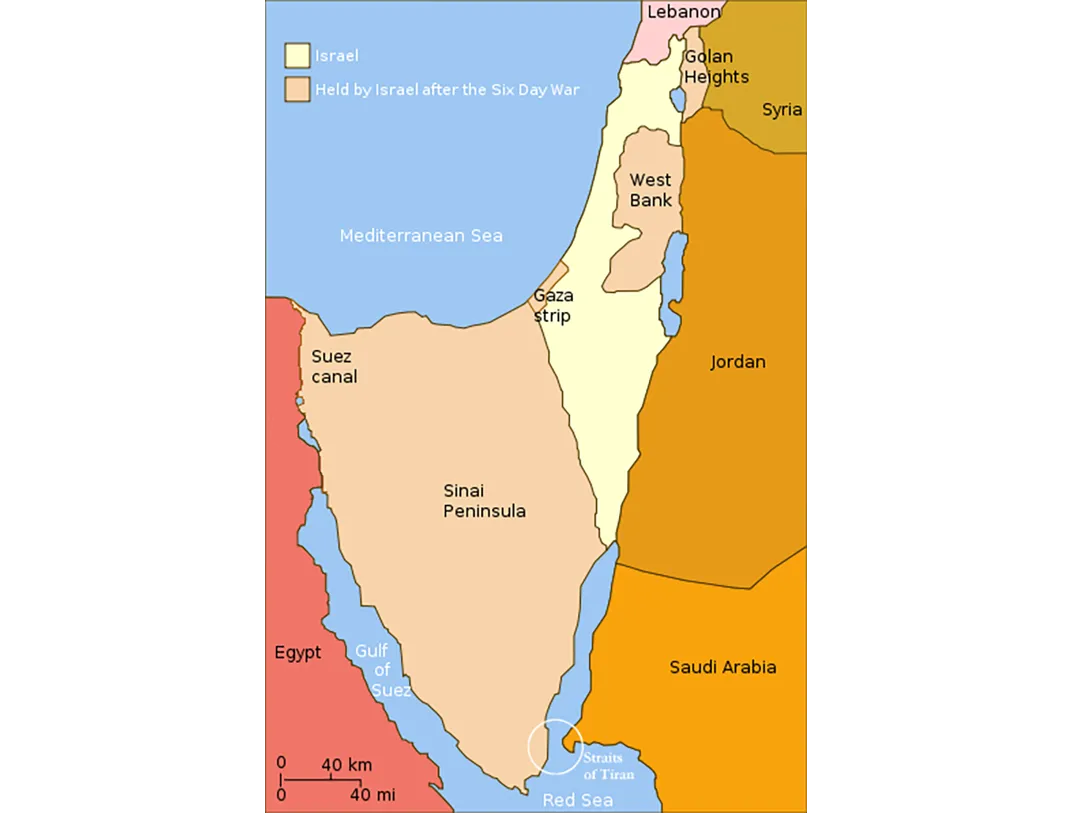

The U.S.S.R. started exerting regional influence in a meaningful way in 1955, when it began supplying Egypt with military equipment. The next year, Britain and the U.S. withdrew financing for Egypt’s Aswan High Dam project over the country’s ties with the U.S.S.R. That move triggered the Suez Crisis of 1956, in which Egypt, with the support of the USSR, nationalized the Suez Canal, which had previously been controlled by French and British interests. The two Western countries feared Egyptian President Nasser might deny their shipments of oil in the future. The summer of that year, Egypt also closed the Straits of Tiran (located between the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas) and the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, effectively creating a maritime blockade. Supported by Britain and France, Israel retaliated in October by invading Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The combined diplomacy of the U.N. and the Eisenhower administration in the United States brought the conflict to a conclusion, with Israel agreeing to return the territory it had captured and Egypt stopped the blockade. To lessen the chance of future hostilities, the UN deployed an Emergency Force (UNEF) in the region.

The Soviet Union continued its close relationship with Egypt after the Suez Crisis, working to establish itself as a power in the region. “This gave it strategic advantages such as the ability to choke off oil supplies to the West and threaten NATO’s ‘soft underbelly’ in Southern Europe,” say Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez, both associate fellows of the Truman Institute at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and authors of Foxbats Over Dimona and The Soviet-Israeli War, 1967-1973.

The U.S.S.R. wasn’t the only Cold War power with an eye on the Arab-Israeli situation. The Kennedy administration also hoped to shore up Arab support by developing a strong relationship with Egypt. In the early 1960s, Kennedy committed the U.S. to providing $170 million worth of surplus wheat to Egypt. That policy was eventually overturned, and the Soviet Union exploited it to grow closer to Nasser.

But Kennedy wasn’t just inserting himself into Arab affairs—he was also working to earn the trust of Israel. In August 1962, Kennedy overturned the previous decade of U.S. policy toward Israel (which stated the U.S. and European powers would support it, but not instigate an arms race). He became the first president to sell a major weapon system to Israel; the Hawk anti-aircraft missile was to be the first in a long line of military supplies Israel received from the U.S. (next up was the A-4 Skyhawk aircraft and M48A3 tanks, approved for sale by the Johnson administration).

While a humanitarian concern may have played a role in Kennedy’s decision, the larger world context was also critical: the U.S. needed a regional ally for the Arab-Israeli conflict, which was transforming into another Cold War stage where allies might mean access to oil.

Just ten years after the conclusion of the Suez Crisis, violence was again becoming a regular element of the region. In the 18 months before the Six-Day War, Palestinian guerillas launched 120 cross-border attacks on Israel from Syria and Jordan. They planted landmines, bombed water pumps, engaged in highway skirmishes, and killed 11 Israelis. Then in November 1966, a landmine killed three Israeli paratroopers near the border town of Arad. Israel responded with a strike on Samu, Jordan, since they believed Jordan had provided assistance to the Palestinian fighters. The attack resulted in the destruction of more than 100 houses, a school, a post office, a library and a medical clinic. Fourteen Jordanians died.

Quick work by American diplomats resulted in a U.N. resolution condemning Israel’s attack, rather than a more immediate escalation of hostilities, but the U.S. intervention did nothing to solve the ongoing problem of Palestinian attacks against Israel.

Which brings us to May 1967, when the U.S.S.R. provided faulty intelligence to Nasser that Israel was assembling troops on Syria’s border. That report spurred the Egyptian president to send soldiers into Sinai and demand the withdrawal of UNEF forces. Egypt then closed the Straits of Tiran to Israel once more, which the Eisenhower administration had promised to consider as an act of war at the end of the Suez Crisis.

The U.S.S.R. were concerned with more than just Sinai; they were also gathering intelligence in Soviet aircraft sent out of Egypt to fly over the Israeli nuclear reactor site of Dimona, according to research by Ginor and Remez.

“If Israel achieved a nuclear counter-deterrent, it would prevent the U.S.S.R. from using its nuclear clout to back up its Arab clients, and thus might destroy the Soviets’ regional influence,” Ginor and Remez said by email. “There was also a deep-seated fear in Moscow of being surrounded by a ring of Western-allied, nuclear-armed pacts.”

For Roland Popp, a senior researcher at the Center for Security Studies, the Soviet Union may have had real reason to think Israel would eventually be a threat, even if the Sinai report they provided Egypt was wrong. And for Egypt, responding may have been a calculated policy rather than a hotheaded reaction, considering that the U.N. had told them the intelligence was faulty.

“I think in retrospect, Nasser wanted an international crisis,” Popp says. “It didn’t matter if the Israelis mobilized troops or not. What mattered was that history had showed the Israelis were hellbent on punishing Syria. The Arabs weren’t capable of militarily containing Israel anymore. Israeli fighter planes could penetrate deep into Syrian and Egyptian airspace without being challenged.”

But Popp also adds that it’s still almost impossible to reconstruct the true motives and beliefs of the protagonists, because there’s little material available from the incident.

Whatever the leaders of Egypt and the Soviet Union may have been thinking, their actions caused acute terror in Israel. Many worried about an impending attack, by an air force armed with chemical gas or by ground troops. “Rabbis were consecrating parks as cemeteries, and thousands of graves were dug,” writes David Remnick in The New Yorker.

Meanwhile, the U.S. remained convinced that Nasser had no real intention of attacking. When President Johnson ordered a CIA estimate of Egypt’s military capabilities, they found only 50,000 in the Sinai Peninsula, compared with Israel’s 280,000 ground forces. “Our judgment is that no military attack on Israel is imminent, and, moreover, if Israel is attacked, our judgment is that the Israelis would lick them,” Johnson said. He cautioned Israel against instigating a war in the region, adding ominously, “Israel will not be alone unless it decides to do it alone.”

For Israelis, it was a moment of crisis. Wait for the enemy to attack and potentially destroy their nation, having not yet made it to its 20th year? Or take the offensive and strike first, risking the ire of the U.S.?

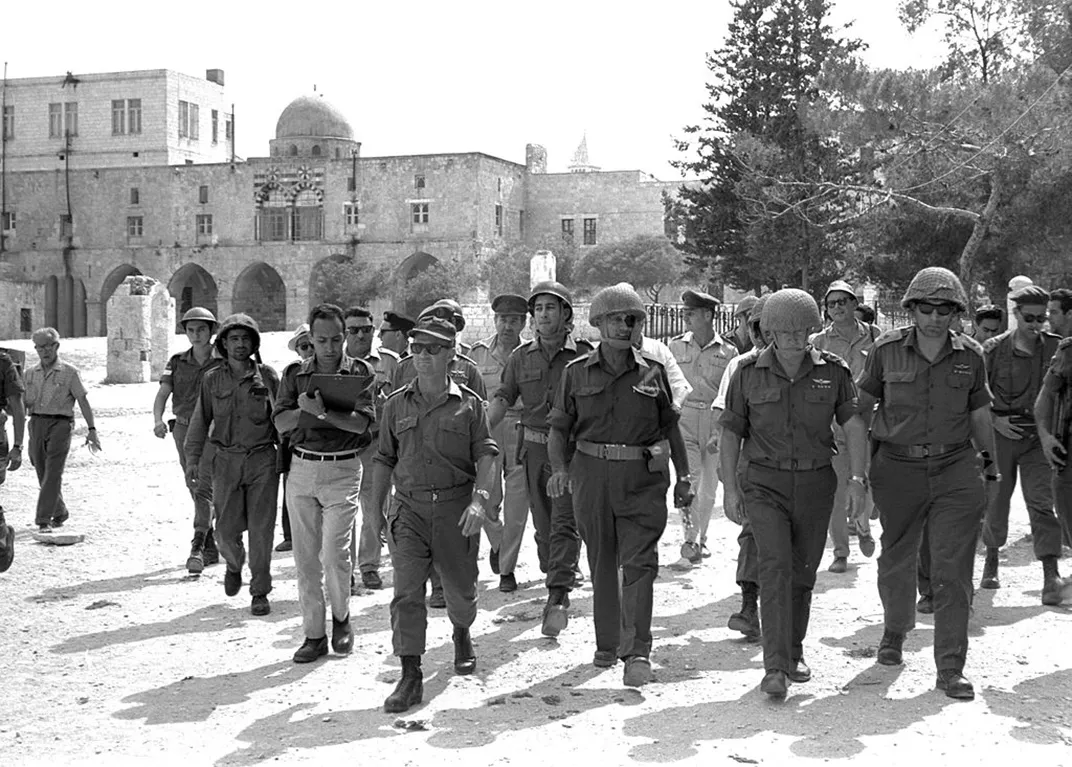

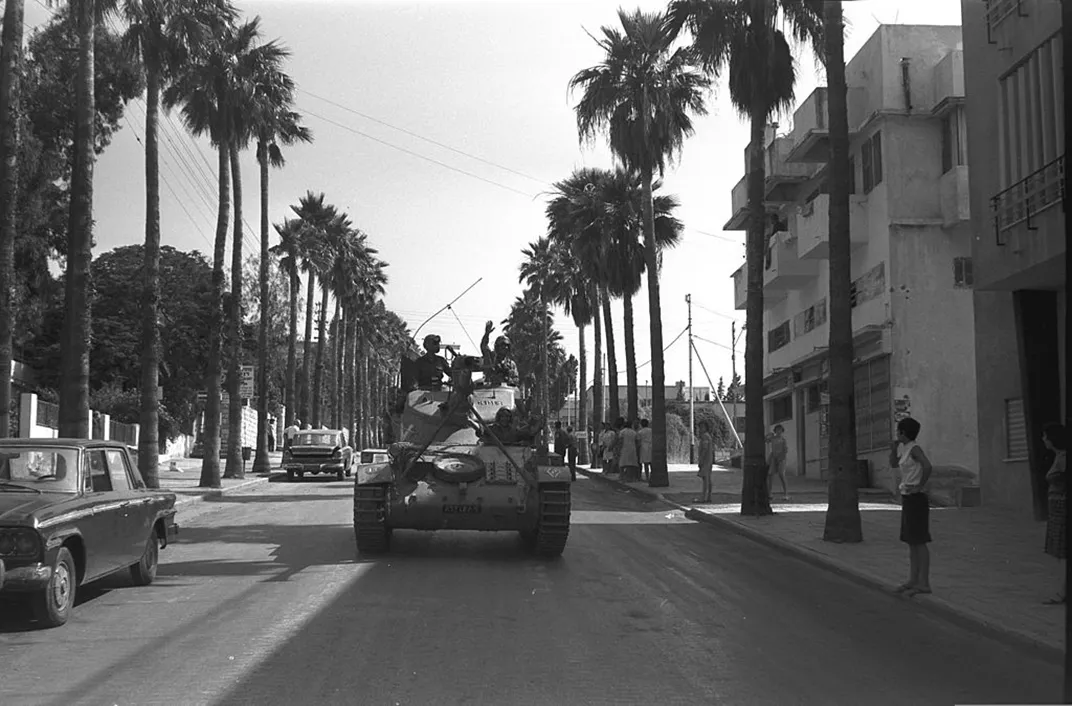

Ultimately, the latter option was chosen. Early on the morning of June 5, 1967, the Israel Air Force launched a surprise attack and destroyed Nasser’s grounded air force, then turned their sights to the troops amassed on the borders of Syria and Jordan. Within six days, the entire fight was over, with Israel dramatically overpowering their neighbors. In the process Egypt lost 15,000 men and Israel around 800. Israel also gained Sinai and Gaza from Egypt, the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria. The little nation had quadrupled its territory in a week.

The immediate aftermath of the war was celebrated in Israel and the U.S., but “the Johnson administration knew the Israeli victory had negative aspects,” Popp says. It meant a more polarized Middle East, and that polarization meant a window of opportunity for the Soviet Union. “There was a good chance [after the war] to find some kind of deal. But you have to understand, the Israelis just won a huge military victory. Nothing is more hurtful to strategic foresight than a huge victory. They didn’t feel any need whatsoever to compromise.”

Most of the territory Israel had won has stayed occupied, and the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian territories today seems as intractable as ever. At this point the U.S. has given more than $120 billion to Israel since the Six-Day War, reports Nathan Thrall, and Israel receives more military assistance from the U.S. than from the rest of the world combined. Today about 600,000 Israelis—10 percent of the nation’s Jewish citizens—live in settlements beyond the country’s 1967 borders. And for Palestinians and Israelis alike, those settlement shave meant terrorism, counterattacks, checkpoints and ongoing hostility.

“What greater paradox of history,” Remnick writes of the Six-Day War’s legacy. “A war that must be won, a victory that results in consuming misery and instability.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)