What Will Happen to Stone Mountain, America’s Largest Confederate Memorial?

The Georgia landmark is a testament to the enduring legacy of white supremacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/2e/292ef1bc-0fce-4123-89ba-de05382ddf40/c6bj03.jpg)

Baltimore uprooted General Lee under the cover of night. New Orleans removed its four Confederate statues to mixed reactions—some voicing relief, others, disapproval. And with the violence that followed the events in Charlottesville, when white nationalists killed one counter-protestor and injured 19 more, the question of how America deals with its history of racism has continued to grow in urgency.

But what’s a state to do when the monument in question is carved 42 feet deep and 400 feet above ground into a granite mountain, with figures of General Lee, General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis larger than the presidential visages of Mount Rushmore?

“We must never celebrate those who defended slavery and tried to destroy the Union… the visible image of Stone Mountain’s edifice remains a blight on our state and should be removed,” said Stacy Abrams, a Democratic candidate for Georgia governor, on Twitter in the days after the Charlottesville violence. And while Abrams is far from the only voice to call for the memorial’s removal, her call has been met by many Georgians who want the memorial to remain untouched.

With arguments raging across the country about the validity of Confederate monuments and whether they offer valuable history lessons or simply perpetuate the inaccurate “Lost Cause” mythology, Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial offers an example of the dark past of some monuments—and shows how hard their removal may be.

A Brief History of a 15-Million-Year-Old Mountain

At 1,683 feet tall, with a base circumference of 3.8 miles, Stone Mountain is an imposing feature in the otherwise even terrain. The granite block is a monadnock, or isolated mountain, created by a pocket of magma trapped underground 300 million years ago and only coming to the surface, through uplift and erosion, 15 million years ago.

As early as 4000 B.C., Paleo-Indians were drawn to the imposing mountain. Soapstone bowls and other artifacts recovered by archaeologists testify to the mountain’s earliest visitors. Researchers later found stone walls erected atop the mountain, likely constructed sometime between 100 B.C. and 500 A.D..

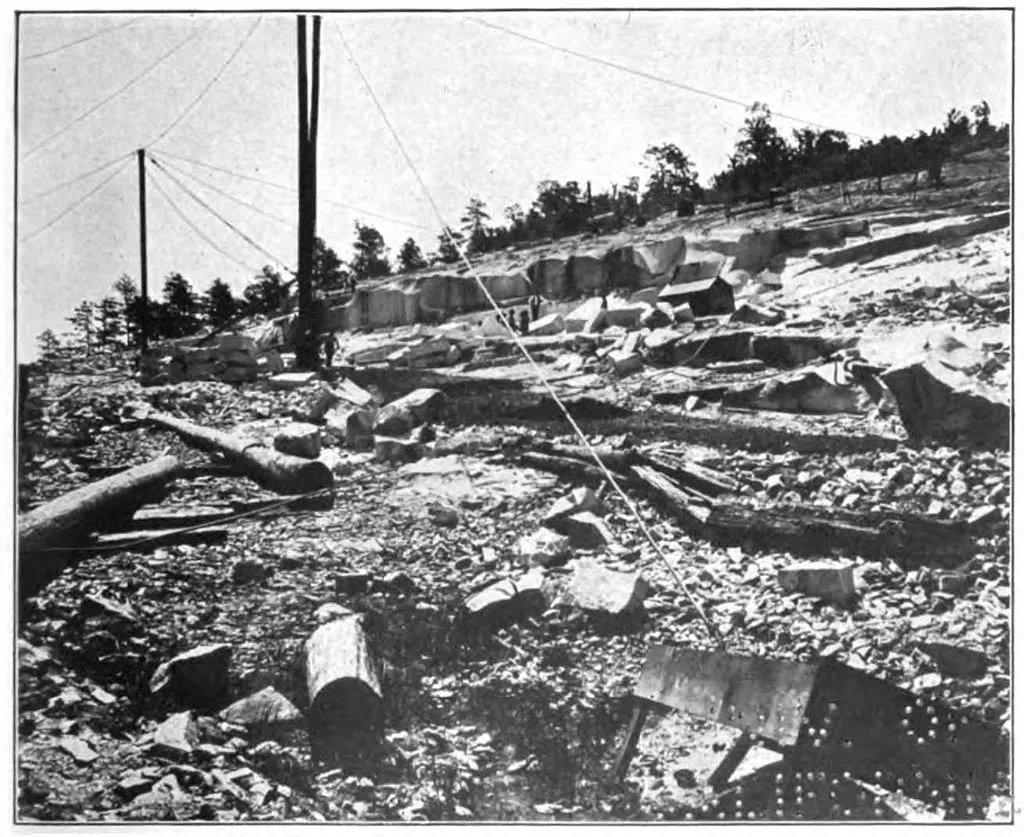

But it wasn’t until the 19th century that humans began exploiting the unique geologic structure on a more massive scale. In 1869, Stone Mountain Granite and Railway Co. began a systematic effort to mine the mountain for stone. That work was taken over by the Venable Brothers in 1882, whose workers harvested 200,000 paving blocks daily, in addition to other sizes of blocks.

With its uniform color, the granite became a coveted building material. Blocks from the Stone Mountain quarry were shipped across the country and around the world. They form the steps on the east wing of the U.S. Capitol; they’re in the locks of the Panama Canal, the structure of Arlington Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., and the Imperial Hotel building in Tokyo; and the blocks were used in dozens of courthouses and post offices across America.

But for all its architectural impact, Stone Mountain had yet to achieve its greatest claim to fame and notoriety. That would come in 1916, with a Civil War widow and a sculptor who later carved Mount Rushmore.

The Birth of a Memorial

“Just now, while the loyal devotion of this great people of the South is considering a general and enduring monument to the great cause ‘fought without shame and lost without dishonor,’ it seems to me that nature and Providence have set the immortal shrine right at our doors,” wrote newspaper editor John Temple Graves for the Atlanta Georgian on June 14, 1914.

His argument was simple, and less provocative than a statement he’d made on lynching a decade earlier (in which he argued lynching was the most useful tool in preventing rape, since “the negro is a thing of the senses… [and] must be restrained by the terror of the senses”). Graves believed the South deserved a monument to its Confederate heroes. Stone Mountain was a literal blank slate, just waiting for a suitable memorial to be carved into it.

Among those Southern citizens who read Graves’s editorial and others like it was C. Helen Plane, a member of the Atlanta United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded in 1895) and honorary “Life President” of the group. At 85, Plane fought as passionately for the memory of her husband and other Confederate soldiers killed in the Civil War as she had done decades earlier. She brought the issue of a memorial before both the city and state chapters of the UDC, quickly gaining the group’s support. While the UDC briefly considered such notable artists as Auguste Rodin to carve the features of General Lee into Stone Mountain, they ultimately settled on Gutzon Borglum.

But after visiting Stone Mountain, Borglum was convinced the UDC hadn’t been ambitious enough in their idea for a bust of Lee. He proposed what would be a 1,200-foot-long carving featuring 700 to 1,000 figures, with Lee, Jackson and Davis in the foreground and hundreds of soldiers behind them. The monumental work would require eight years and $2 million to complete, though Borglum estimated the main figures could be finished for just $250,000 (almost $6 million today).

“The Confederacy furnished the story, God furnished the mountain. If I can furnish the craftsmanship and you will furnish the financial support, then we will put there something before which the world will stand amazed,” Borglum announced before an audience of potential sponsors in 1915.

While the amount Borglum required seemed impossibly high, Plane pushed forward with her fundraising efforts, writes David Freeman in Carved in Stone: The History of Stone Mountain. Plane also secured a land deed from the Venable family, with patriarch Sam Venable even inviting Borglum to his home at the foot of the mountain.

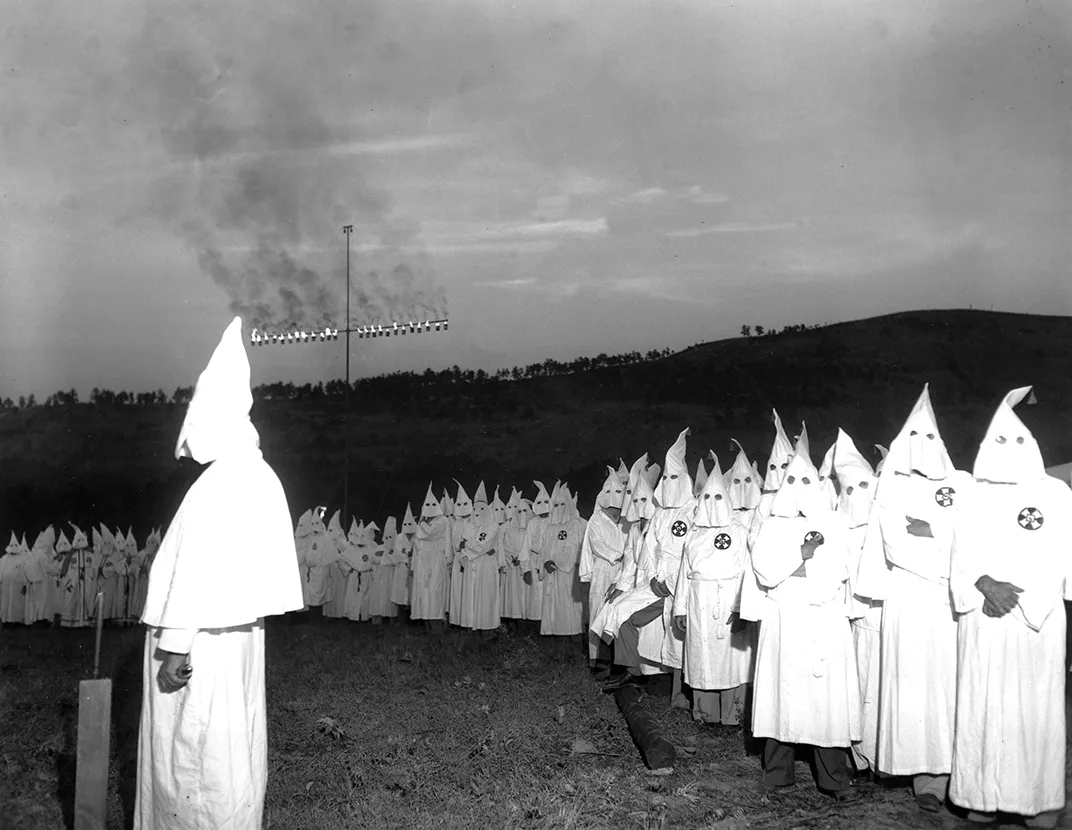

But the sculptor wasn’t the only person Venable welcomed to his property in the fall of 1915. He also befriended William Simmons, who ushered in the modern era of the Ku Klux Klan, founding the Second KKK at the top of Stone Mountain on November 25, 1915. That night, more than a dozen men gathered to become part of a resurgent white supremacy group that had mostly died out in the late 1800s. Inspired by the film Birth of a Nation, they burned a cross and swore their loyalty to the Klan, ushering in a new era of white nationalist terrorism.

Venable himself, who was part of the ceremony, quickly rose through the ranks of the KKK, allowing the group regular use of his grounds. As Paul Stephen Hudson and Lora Pond Mirza write in Atlanta’s Stone Mountain: A Multicultural History, “Their meeting place for decades was known as the ‘Klan Shack’ in Stone Mountain Village.”

But the overlap between the memorial and the Klan didn’t end with their geographical origins. At one point, Borglum considered including the KKK in his monument at the prompting of Plane, who wrote:

“The Birth of a Nation will give us a percentage of next Monday’s matinee. Since seeing this wonderful and beautiful picture of Reconstruction in the South, I feel that it is due to the Ku Klux Klan which saved us from Negro domination and carpet-bag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain. Why not represent a small group of them in their nightly uniform approaching in the distance?”

Although Borglum ultimately declined to include the figures in his carving, he agreed the KKK should have some recognition in the memorial, perhaps in a room carved out of the mountain. But none of his plans were destined to be achieved. By 1924 he had only completed Lee’s head, having been delayed by World War I, and a disagreement between Borglum and the managing association resulted in him leaving the project in 1925. But he wasn’t between jobs for long; Borglum went on to work on Mount Rushmore, a project that lasted him from 1927 till 1941.

Meanwhile, the Klan’s membership exploded to more than 4 million members, and in 1925 they marched on Washington, D.C. Wherever the group popped up, acts of terror committed against innocent African-Americans, Catholics and immigrants were sure to follow.

Reclaiming the South from the Civil Rights Movement

With only three years to go before the land deed from the Venables was set to expire (they had granted 12 years to finish the memorial), a second sculptor was brought in. But Augustus Lukeman barely had time to remove the work Borglum had done and start work on a carving of three figures on horseback when he was forced to abandon the project in 1928.

The deed expired, the Venable family took back their property, and the mountain remained untouched for 36 years. Although the Georgia state government attempted to gain recognition for Stone Mountain from the National Park Service, they were informed that scarring from the earlier granite quarries and the incomplete carvings destroyed the mountain’s natural value.

But with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that segregated schools were unconstitutional, and the growing influence of the Civil Rights Movement, the time had come for renewed action. “So long as Marvin Griffin is your governor, there will be no mixing of the races in the classrooms of our schools and colleges of Georgia,” Griffin informed his constituents in 1955 during his inaugural address. With help from the Georgia General Assembly, Griffin went on to purchase the mountain, using $1 million in public funds. He then made the Stone Mountain Memorial Association a state authority, meaning the governor would appoint the board of directors but the association would receive no tax dollars. To historian Grace Elizabeth Hale, the motivation for doing so couldn’t be clearer.

“State politicians formed Stone Mountain Park as part of an effort to ground the white southern present in images of the southern past, a sort of neo-Confederatism, and halt nationally mandated change in the region,” Hale writes. “For the governor and other supporters of the new plans, the completion of the carving would demonstrate to the rest of the nation that ‘progress’ meant not black rights, but the maintenance of white supremacy.”

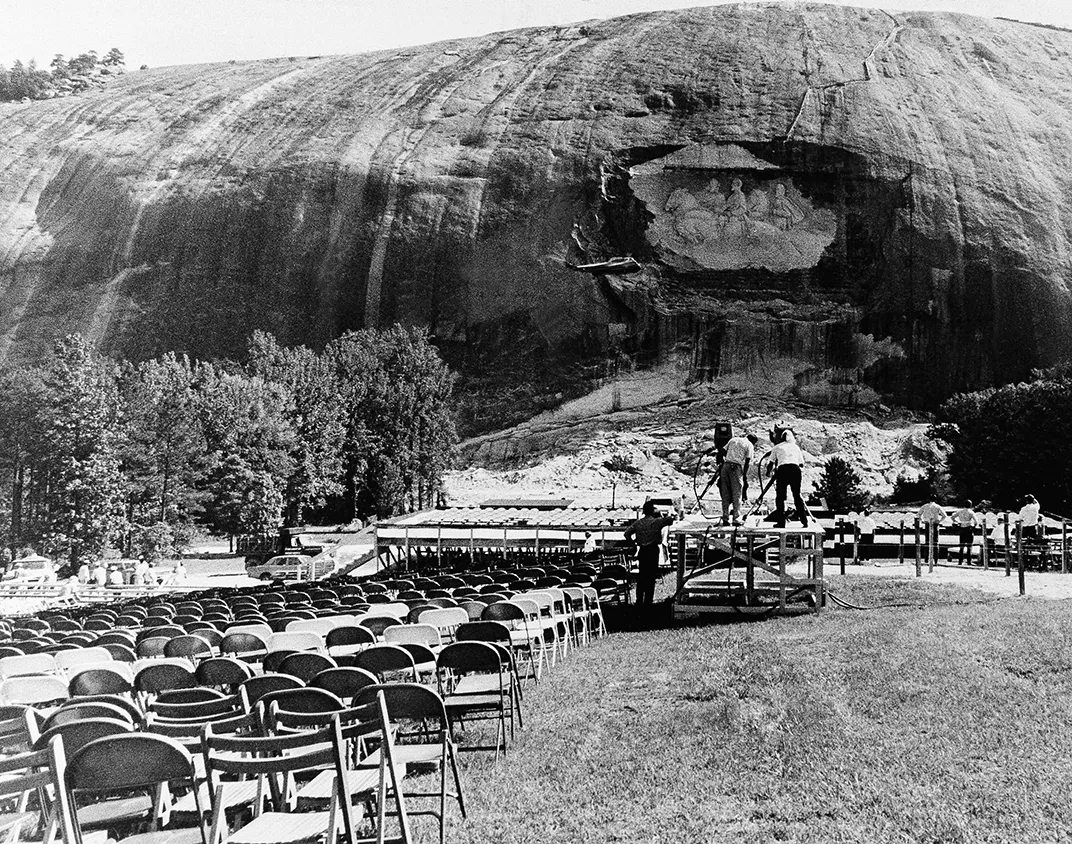

After Walter Kirkland Hancock was chosen to lead the sculpting efforts, work resumed in 1964 after a nearly-40-year hiatus. The dedication ceremony was held May 9, 1970, and the memorial was finally completed in 1972, with fine enough detail that the eyebrows and belt buckles were visible, the sculpture large enough that a grown man could stand inside one of the three horse’s mouths. The memorial became the largest high relief sculpture in the world, depicting Davis, Lee and Jackson on horseback, their figures stretched across three acres.

An early version of the park beneath the sculpture included a replica plantation, where slave quarters were described as “neat” and “well furnished” in promotional materials. The slaves were called “hands” or “workers,” Hale writes, and black actor Butterfly McQueen was hired to provide visitors with information about the park.

Sandblasting the Confederacy

Today, with 4 million visitors coming to the park each year, the mountain has changed little but the message has shifted. While nature and the memorial are still featured, its theme-park attractions include a 4-D movie theater, a farmyard, miniature golf, a dinosaur-themed playground and more. As far as educational experiences are concerned, a museum includes exhibits on the monument’s history and geology, and an adapted version of the plantation, called “Historic Square” features original and replica buildings and relays information about the antebellum period.

While the violence at Charlottesville spurred new debates over Confederate monuments, controversy surrounding the Stone Mountain Memorial is nothing new. As part of a 2001 political compromise to change the segregation-era state flag so it no longer included symbols of the Confederacy, lawmakers in Georgia’s General Assembly agreed to a statute that protects plaques, monuments and memorials dedicated to military personnel of the U.S. and the Confederate States of America. This, of course, includes Stone Mountain.

“Many members of the [Georgia Legislative Black Caucus] weren’t completely comfortable with it, but we thought that was a compromise to make,” says Lester Jackson, a Georgia state senator from Savannah. “Fast forward 15 years and we need to go back and revisit that.”

In 2018, Jackson and others plan on introducing a resolution in the Georgia state government that would establish a study of all the Confederate monuments in the state. The study will provide evaluations of the monuments based on when they were erected and with what intentions, and recommendations for how to move forward in removing or replacing them.

“When we start removing the symbols of hate and separatism and racism, that’s an important start to becoming one nation of one people,” Jackson says.

But the political process would be lengthy and likely controversial, considering 62 percent of people surveyed in a recent poll believe Confederate statues should remain standing, reports Clare Malone at FiveThirtyEight. And that’s not even taking the practicality of the project into consideration.

“The removal of the carving is not a trivial matter,” said Ben Bentkowski, president of the Atlanta Geological Society, by email. “You just can’t come in the night and remove it.”

Because the carving is 42 feet deep into the mountain, and hundreds of feet wide and tall, even controlled blasting could be dangerous for workers and bystanders. That said, the granite itself is solid, so sandblasting the sculpture wouldn’t affect the structural integrity of the mountain. And although he couldn’t provide a definite estimate for the cost of such an undertaking, Bentkowski believed it would “take millions of dollars to do it safely and not leave just a blast-scarred face of the mountain.”

Another solution goes in the opposite direction of destruction: why not add more to the sculpture? Figures proposed to balance history out have included Martin Luther King, Jr. and, more facetiously, Atlanta-based hip-hop duo Outkast. But this, too, would be a costly endeavor and is currently outlawed under the 2001 statute.

While Abrams and others have called for the sculpture’s removal, politicians on the opposite side of the issue have come to its defense. “Instead of dividing Georgians with inflammatory rhetoric for political gain, we should work together to add to our history, not take from it,” said Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle of Abrams’ position, reports the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

There’s no easy answer when the monument in question is carved into a mountain, when Confederate generals continue to provoke strong emotions. What the debate boils down to is whose version of history will endure. And even when you have a 1,000-foot-granite wall at your disposal, it will never be enough space to capture the complexity of the nation’s centuries-long struggle with the legacy of slavery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)