The History of American Impeachment

There’s a precedent that it’s not just for presidents

:focal(1485x771:1486x772)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/0a/5d0a9727-0703-4da0-bdcc-48d42f8b8d10/ap_731121013.jpg)

In April 1970, Congressman Gerald Ford provided a blunt answer to an old question: “What is an impeachable offense?”

Ford, then the House minority leader, declared, “An impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.” At the time, he was leading the charge to impeach Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a staunch liberal he accused of financial impropriety.

Ford’s memorable definition may not be textbook, but it certainly sums up the spirit of American impeachments—judicial and otherwise. But what does the Constitution itself say about impeachment?

As the Constitution’s framers sweated and fretted through the Philadelphia summer 230 years ago, the question of impeachment worried Benjamin Franklin. America’s elder statesman feared that without a means to remove a corrupt or incompetent official, the only resort would be assassination. As Franklin put it, this result would leave the political official “not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character.” Perhaps he had Julius Caesar and the Roman Senate in mind.

Ultimately, the framers agreed with Franklin. Drawn from British parliamentary precedent, impeachment under the Constitution would be the legislature’s ultimate check on executive and judicial authority. As the legislative branch, Congress was granted the power to remove the president, vice president, “and all civil officers of the United States” from office upon impeachment and conviction.

There was some debate about which crimes would be impeachable, but the framers left us with “Treason, Bribery or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Though the first two are pretty clear-cut, the rest of the definition leaves considerably more wiggle room. But the Constitution offers much more clarity on the process itself.

There is, first, an important difference between impeachment and conviction. It is the basic distinction between an indictment—being formally charged with a crime—and being found guilty of that crime.

The process begins in the House of Representatives, which has the sole power to impeach. In modern times, impeachment proceedings begin in the House Judiciary Committee, which investigates and holds hearings on the charges. The committee may produce an impeachment resolution that usually contains articles of impeachment based on specific charges. The House then votes on the resolution and articles, and can impeach by a simple majority.

Then comes the trial. Under the Constitution, the Senate has the sole power to hear the case, with House members acting as prosecutors. Attorneys for the accused can present a defense and question witnesses. The accused may even testify. If the president or vice president has been impeached, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the trial. In other cases, the vice president or the president pro tempore of the Senate is the presiding officer.

At the end of the hearing, the Senate debates the case in closed session, with each senator limited to 15 minutes of debate. Each article of impeachment is voted on separately and conviction requires a two-thirds majority—67 of the 100 senators.

To date, the Senate has conducted formal impeachment proceedings 19 times, resulting in seven acquittals, eight convictions, three dismissals, and one resignation with no further action.

Gerald Ford knew how high that bar was set. In 1970, he failed in his attempt to impeach Douglas. The FDR-appointed liberal justice had already survived an earlier impeachment attempt over his brief stay of execution for convicted spy Ethel Rosenberg. This time, the supposed offense was financial impropriety, but Ford and others also clearly balked at Douglas’s liberal views. The majority of the House disagreed, and Douglas stayed on the bench.

So far, only two American presidents have been impeached and tried in the Senate: Andrew Johnson—Lincoln’s successor—and Bill Clinton. Both were acquitted. Richard Nixon would certainly have been impeached had he not resigned his office in August 1974.

Of the other impeachment cases since 1789, one was of a senator—William Blount of Tennessee, case dismissed in 1799—and one a cabinet officer, Secretary of War William Belknap, who was acquitted in 1876. Most of the other impeachment cases have involved federal judges, eight of whom have been convicted.

Among those impeached judges was Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. In 1805, the Senate acquitted Chase after a trial notorious for its partisan politics. Vice President Aaron Burr, who presided over the Senate proceedings, was praised for his evenhanded conduct during the trial. Of course, Burr had recently killed former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel. He returned to Washington to oversee the Chase trial while himself indicted for murder in New York and New Jersey. Never arrested or tried in Hamilton’s death, Burr escaped impeachment when his term expired.

After Nixon’s close encounter with impeachment in the summer of 1974, Gerald Ford secured another spot in the history books as the first man to become Commander in Chief without having been elected president or vice president. He set another precedent with the pardon of his disgraced predecessor. Ford’s bare-knuckles dictum about the politics of impeachment still reflects the reality of Washington.

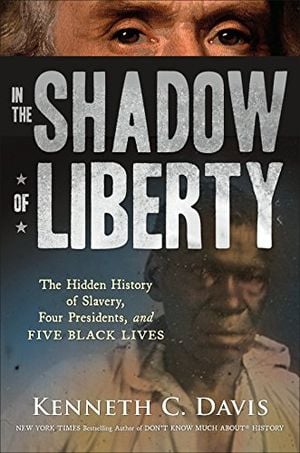

Kenneth C. Davis is the author of Don’t Know Much About History, Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and, most recently, In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives. His website is www.dontknowmuch.com.