When Newspapers Reported on Gun Deaths as “Melancholy Accidents”

A historian explains how a curious phrase used by the American press caught his eye and became the inspiration for his new book

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/29/432968ae-9869-4fd8-a620-3c7dcd24a556/42-26407210_resize.jpg)

Earlier this month, a gun rights activist made national headlines when her four-year-old son shot her in the back with her handgun while she was driving. Her story, unsurprisingly, drew intense scrutiny. A Facebook page she operated featured posts such as, “My right to protect my child with a gun trumps your fear of my gun,” which in turn lead to many online commenters to take a seemingly perverse, outsized pleasure in her suffering. One Slate reader commented on a story about the case, “While it’s good she didn’t die, she got what she deserved.” (Meanwhile, her county Sheriff’s office is pursuing misdemeanor charges for the unsafe storage of a firearm and, according to The Gainsville Sun, the state has opened a child protective investigation.)

Though the story has a distinctly 21st-century feel to it, at its core, it’s a story older than our country, and that it reached a wide and vociferous audience is, actually, nothing new either. Accidental gun deaths and injuries, especially those inflicted on family members, are as American as apple pie – at least according to American religious history scholar Peter Manseau.

In 2012, while at work on his previous book, One Nation Under Gods, Manseau discovered a genre of newspaper reports dating back to colonial America called “melancholy accidents.” As he explains in the introduction to his new book, Melancholy Accidents: Three Centuries of Stray Bullets and Bad Luck, “Though these accident reports also took note of drownings, horse tramplings, and steamship explosions, guns provided their assemblers with the most pathos per column inch.” Over four years, Manseau read and collected hundreds of these reports, ultimately gathering more than 100 of them into his book, which contains reports spanning nearly two centuries of American history.

Melancholy accidents “bridge a gap not of geography or politics, but of time,” Manseau writes about the reports. In America, the news media continues to write news stories about accidental gun deaths, and it seems unlikely the feed will ever stop. As one report from 1872 reads, “We thought a good strong frost would put an end to shot-gun accidents, but people still blaze away at themselves.”

And, as Manseau discovered in his research, the accidents themselves are not the only constant. The way we react to them has remained surprisingly similar, too. From the time when we called these deaths and injuries “melancholy accidents” through to today, the age of the hashtag #gunfail, history has shown us to be a people who can’t live with their guns, but won’t live without them.

Manseau spoke to Smithsonian.com about his research, the book, and what he calls the “alternate history of guns in America” that he discovered in the melancholy accident reports.

You mention in the introduction that you stumbled upon the phenomenon of “melancholy accidents” while doing historical research. What were you researching when you discovered melancholy accidents and when did you realize you wanted to collect these accidents and publish them?

My last book, One Nation Under Gods, told the story of religion in America from the point of view of religious minorities, going back into the early 18th century. I was reading a lot of newspaper accounts looking for evidence of religious minorities, and while I was doing that research, I kept coming across this phrase “melancholy accidents.”

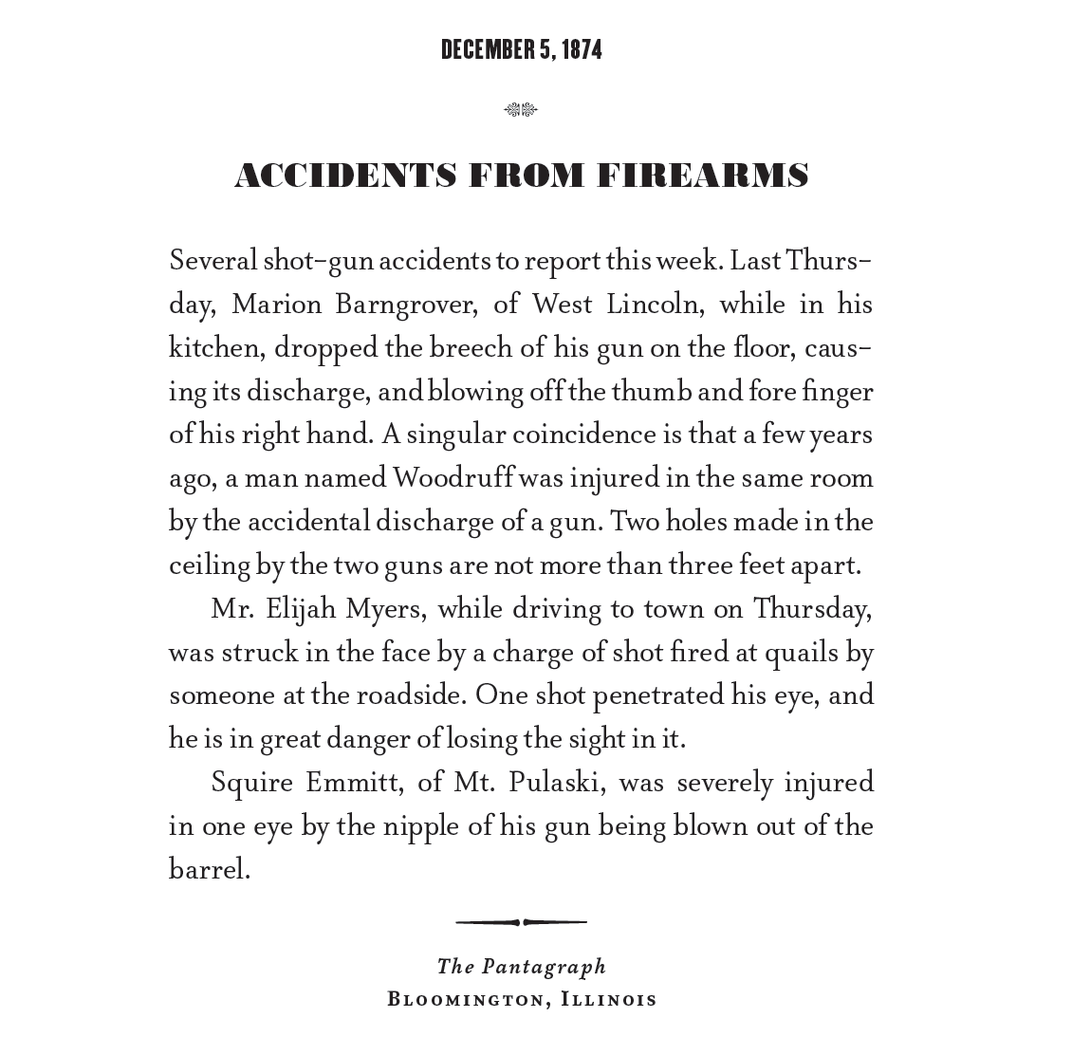

This was a genre of newspaper reporting that seems to have started in England and was brought to colonial America very early on. It would often refer to people drowning in rivers or being blown up by steam ships and that sort of thing, but what seemed most common for “melancholy accidents” was that they were gun accidents. They were reports of musket exploding or misfiring, killing the person who was using it or someone who happened to be unfortunate enough to be nearby.

It began to seem to me that the genre of gun accident reports has been part of American journalism from the very beginning. The stories spoke to each other across the centuries as this genre of journalism, this type of American storytelling that endured no matter what changes were going on politically or within the population as it changed. That struck me as a fascinating thing, that here was something that remained unchanging in American culture throughout the centuries.

Had you heard of “melancholy accidents” before?

Other scholars have noted them, but not specifically having to do with guns so, after I discovered them for myself, I began to research them.

This is my sixth or seventh book, and it was a great relief as a writer to write with other people's words, to compile these reports and let them speak for themselves. I found that they had a power that is difficult to bring in your own writing.

How systematic were you in looking for them? Is the book a small representative slice of all of the melancholy accidents reported from 1739 to 1916 or is this the grand total of melancholy accidents on public record?

I really could have included, without exaggeration, hundreds more. These were published in dozens of newspapers for centuries. I continue to find new ones, in fact, and often I'll find a new one and think, “I wish I had included that in the book.” They are really such a fascinating window on lives lived long ago.

Many of them are just so haunting. The style of early American newspaper writing is, in some ways, very spare and yet, in other ways, is very florid in its language. There’s something about them. They’re so different from the way we write stories now, or different from the way we often read stories now. It gives them this haunting quality. They linger and you can really feel the anguish felt by the people on the page.

Why did you stop at 1916?

I could have continued well past 1916, all the way up to today, certainly. I chose 1916 because it is 100 years before today exactly, but also because something seems to happen with the arrival of the First World War to the way violence is spoken about in the American press. It also seems the be the end of this phrase “melancholy accidents.” It doesn't turn up in the press at all as far as I can remember after that. In the 20th century, it began to seem archaic in a way it wasn’t before and so it seemed to me a natural stopping point.

Can you talk about some of the things you realized about America’s relationship with guns through history?

One of the things that I kept running into was this idea of divine indifference. We think of colonial America and the young United States as being a very religious place, and yet when you read these gun accident reports, they give this sense of feeling that if you come in contact with guns, you're ruled suddenly, entirely by fate, that God takes no interest in how people are interacting with guns, and there's no question or lament about this: How did this happen? How do bad things happen to good people? It's just a feeling that if we choose to make guns a part of our lives, this is bound to be part of our experience, and we are bound to experience this again and again.

How has gun culture in our country evolved over time?

Guns play a very different role in American society today than they used to. Once upon a time, they were, for many people, tools that you would use for sustenance. You might feel you needed to have them for protection if you are living in remote places and need to defend yourself against wolves and bears and whatnot. They were very practical tools for early Americans.

For Americans today, they seem to be far more often tools of enjoyment and tools of hobbyists, and that very fact makes them entirely different objects as far as what they mean to Americans. That, to me, makes them far less necessary. And yet, as they have become less necessary, they have also become a symbol of the clash between those who use them for enjoyment and those who fear those who use them for enjoyment. They've become a symbol of this clash within the culture in a way that they were not in early American history.

Have the ways that we’ve struggled to come to terms with accidental gun deaths changed?

I guess we've come to terms with them in the sense that they keep happening, and we all just throw up our hands about it and say, “Well, that's what happens when you have guns in your life, that's what happens when you have so many guns in your country, when you have as many guns in the United States as there are people.” They're bound to intersect in these fatal ways very often, and so there's a sense of resignation, this helplessness that this is bound to continue to happen.

And that’s very similar to what I found in these early accident reports, this feeling that if you have objects in your life that are designed to kill, you have to assume that they will do so very often, even when you don't want them to. The feeling of helplessness in the face of guns endures.

The reason I collected these stories and chose to retell them the way I did, was that I hoped to provide a kind of corrective to the stories that we usually tell about guns. Guns within American culture, the way we think and talk about them, there's so much determined by the mythology of the frontier or the mythology of the western. We think of guns as being these heroic machines that allow for the preservation or protection of freedom. And yet I started to wonder as I collected these stories, what if that is not the most enduring meaning of guns? What if the most enduring meaning is not heroism, but tragedy? What if accidents are really what happens far more often with guns than them being used as they are intended? I wanted to propose another, an alternate history of guns in America, through these primary sources to let them speak for themselves.

I really didn't write the book with any kind of political agenda, though. I have no problem with hunting culture or responsible gun use, people who choose to own and use guns for recreation. I have no problem with any of that, and I don't expect that anyone's going to read this book and suddenly say, "I had no idea how dangerous guns could be!"

Gun owners know that best of all. They know far better than people who never get close to them how dangerous they can be. But I did want to open up this view of the past that shows how these accidents are far from a modern phenomenon. These small-scale tragedies have shaped our experience with guns entirely from the beginning. I am, first of all, a person interested in the stories and to me, that’s how these accidents reports resonate.

Some of these are stunningly tragic; others have a note of dark humor. Were there any melancholy accidents that stayed with you or affected you most?

The ones that stay with me for their tragedy are usually the parents who accidentally take the lives of their children. The telling of those stories, with just a sentence or a detail, make it so easy to imagine yourself into that situation and know the pain they must have felt. For me those are the most haunting.

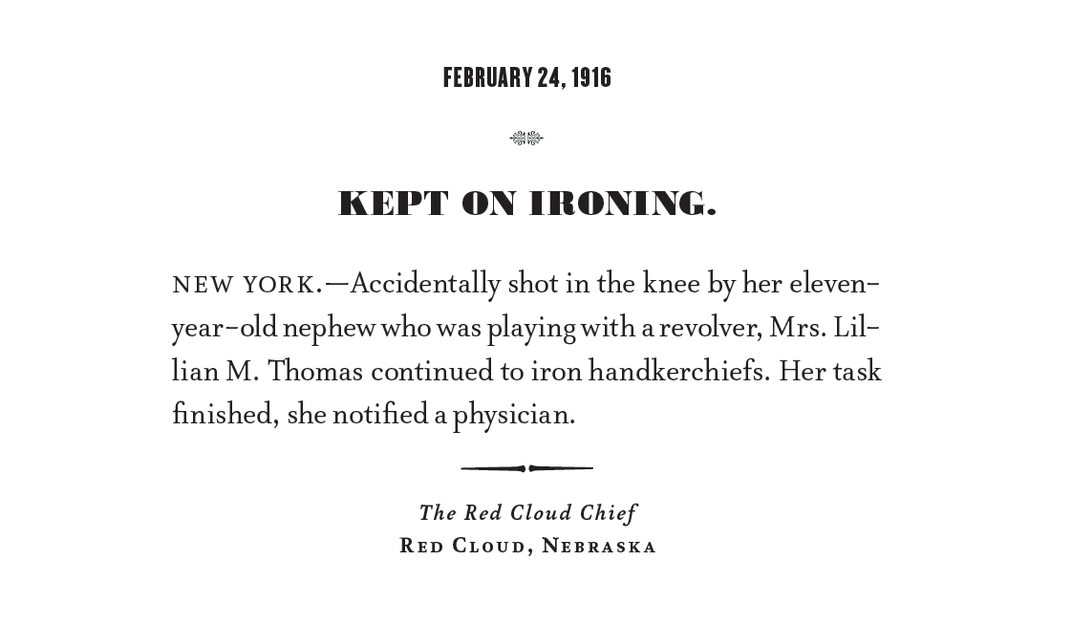

But again and again I would find these accident reports that you just couldn’t help laughing at. One I'm thinking about right now is a woman who was doing her ironing, she's ironing handkerchiefs, and she's accidentally shot in the leg. The accident report is careful to note that she finished her ironing before she called a physician. It's a very funny situation to read on the page. It's also suggestive of the way the accidents, all told, are taken in stride.

Every day there's a new gun accident in the news. When we read about them, we either find them absurd and funny or terribly tragic, and yet we take them in stride, we go about our business, because this is what life with guns is, it's what it means. We hear the gunshot and we go on with our ironing.

How long did the project take?

The book actually began as a little piece I wrote for the New Yorker three years ago this month. But they just lingered with me, the idea of them. And so I kept looking for them. I began finding them accidentally, but then I began looking for them, and that's when I couldn't stop. It became this obsession for a little while, finding these and wanting to show them to world. All told, off and on it was probably a matter of four years I spent wondering about melancholy accidents.

Was it difficult to do so much research on private and personal tragedies?

I didn’t find it ultimately depressing. The interesting thing about the melancholy accidents is that they are ultimately not about death. They are ultimately about the living, about the people who survive and how they deal with this tragedy. That's true of any stories of tragedy, I think. It's ultimately about what comes next and what we can learn from it. I think they raise questions that anyone living asks about what it means to be alive and how we endure in the face of such tragedies.

One that topic, some of the reports talk about the grief that the shooters feel afterwards, how they dealt with it for the rest of their lives. Has that changed over time?

The accident reports go into such detail of the grief these people felt, whether it was a brother who accidentally killed his sister and then they had to try to stop him from taking his own life after seeing what he had done, or the father who accidentally killed his child and then the report notes that he himself died of a broken heart weeks later… I imagine that the feelings of grief have changed very little, no matter how much the technology of the weapons has changed or the way we think about weapons as a culture has changed. That part seems, to me, to endure.

A difficult part of being involved in a tragedy like this today is that you probably can't escape it in the way that you could then. The digital trail of having your name associated with one of these things is going to follow you for the rest of your life. With the book coming out, I've been doing more research on gun accidents more recently, and I happened to come across an article from sometime in the early 90s. It showed a picture of a little boy with his mother, and it noted that the little boy had accidentally killed his baby sister with gun. I thought, “That little boy in the early 90s is now a grown man. No doubt he still lives with that.” And his story, his pain, is there to be found by anyone who happens to stumble across it online. It's a way that the tragedy continues to echo.