When America’s Titans of Industry and Innovation Went Road-Tripping Together

Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and their friends traveled the country in Model Ts, creating the Great American road trip in the process

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/6c/af6c0163-854d-40e1-9dae-e17faf4f9764/sf22408-edit.jpg)

Road trips are synonymous with American life—but they weren’t always so. In the early 20th century, a few celebrity friends gave the tradition of disappearing down a lonesome highway a jump-start.

When Henry Ford debuted the Model T in 1908, not everyone appreciated its promise. The famous nature writer John Burroughs denounced it as a “demon on wheels” that would “seek out even the most secluded nook or corner of the forest and befoul it with noise and smoke.” Ford was a fan of Burroughs and a keen bird watcher. He believed his affordable family car would grant greater access to the American wilderness. He sent the disgruntled writer a new Model T as a peace offering.

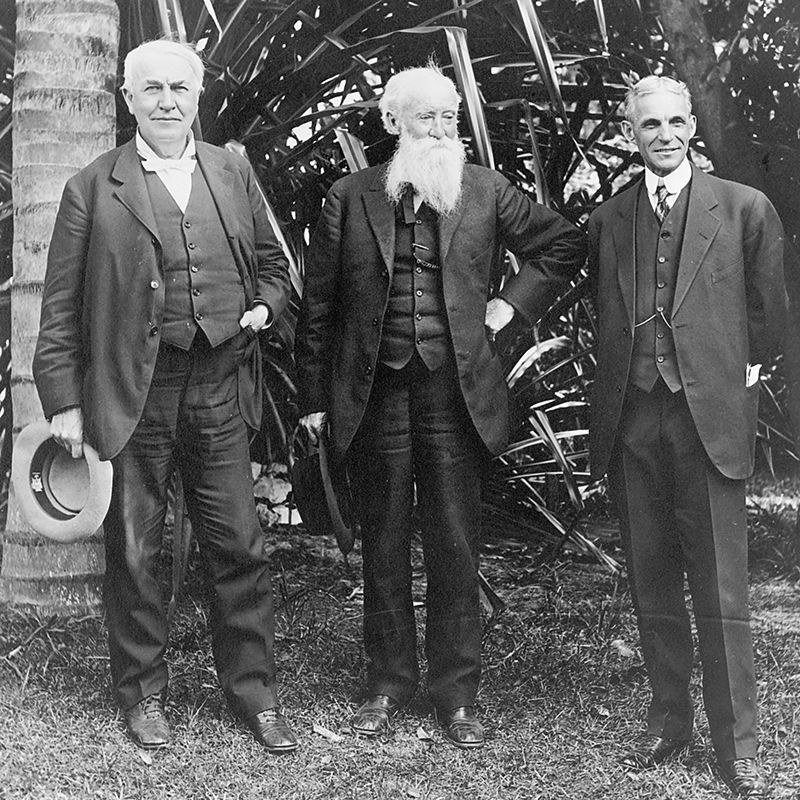

It worked. “Out of that automobile grew a friendship,” Ford wrote in his memoirs. “And it was a fine one.” Ford introduced Burroughs to two other titans of American industry: inventor Thomas Edison and tire manufacturer Harvey Firestone. Between 1914 and 1924, these influential men loaded their autos with camping gear and embarked on a series of historic road trips.

The self-titled “Vagabonds” toured the Everglades, the Adirondacks, the Catskills and the Smoky Mountains. They cruised down California’s sparkling coast and threaded through the maple forests of Vermont, reveling in the break from their duties as national powerbrokers. The annual forays into the wild lasted two weeks or longer.

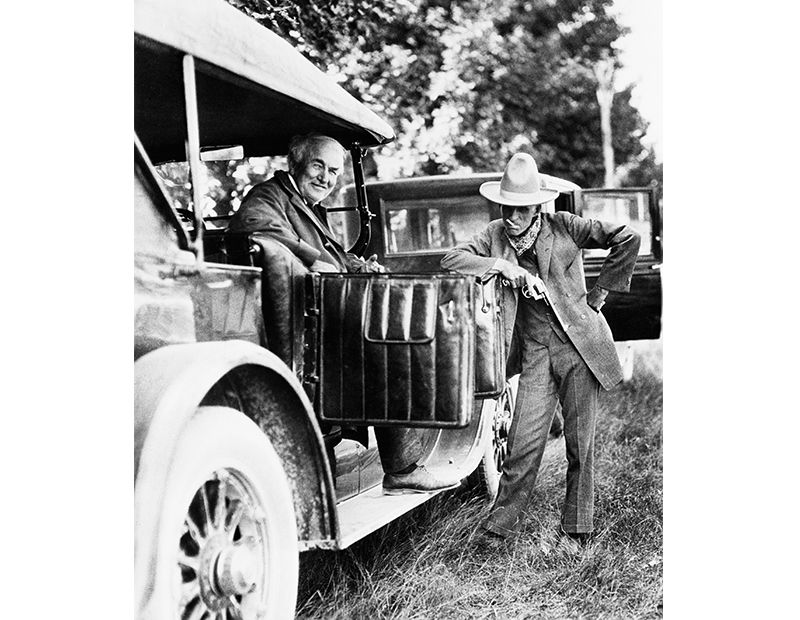

At an average clip of 18 miles per hour, the caravan of Tin Lizzies chugged along across a changing America. Paved roads were sparse then, and interstate highways non-existent. Hand-drawn road signs warned: “DRIVE SLOW-DANGEROUS AS THE DEVIL.” Edison usually chose the route. He rode in the front car, acting as captain and navigating pitted dirt roads with a compass and a handful of atlases. The intrepid inventor preferred back roads and avoided major towns. He made an exception for the brand new Lincoln Highway. Still under construction, it was touted as the first cross-country motorway that would eventually connect New York to San Francisco.

Roadside cafés, service stations and infrastructure to support auto touring did not yet exist, but that was no trouble for these pioneers. Ford served as the energetic mechanic. He soldered busted radiators back together and organized tree-climbing, wood-chopping and sharp-shooting contests during pit stops. Firestone supplied the meals and impromptu poetry recitations. The elder Burroughs, with his Whitman-esque white beard and back-to-nature philosophy, led botanical hikes wherever camp was pitched. He taught the others to identify the local plants and birdsong.

Burroughs chronicled the gang’s adventures in “A Strenuous Holiday,” an essay published posthumously. “We cheerfully endure wet, cold, smoke, mosquitoes, black flies, and sleepless nights, just to touch naked reality once more,” he wrote.

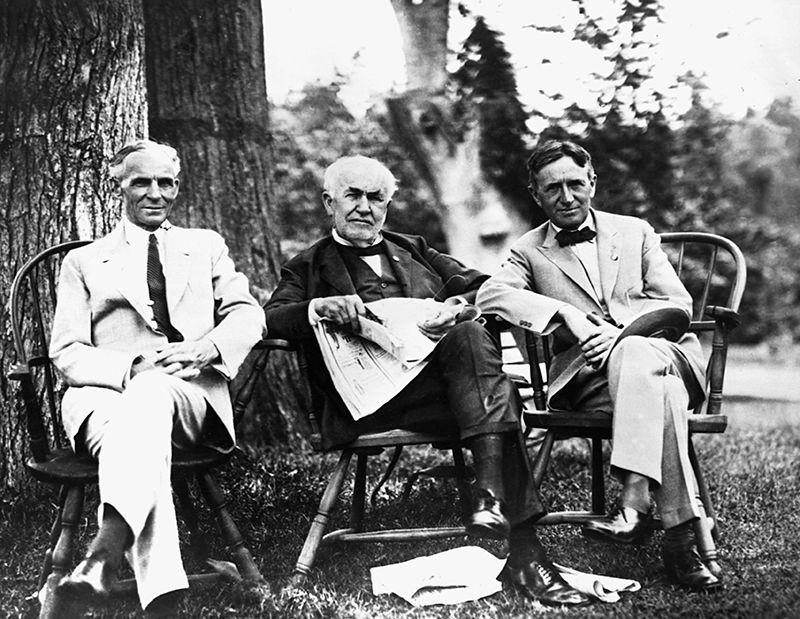

Naked reality was a slight exaggeration for these genteel outings. It’s true that Edison encouraged his comrades to “rough it” and forbade shaving during the trips. But the men often broke that rule—particularly when their wives tagged along. And the gourmet kitchen staff still wore bow ties.

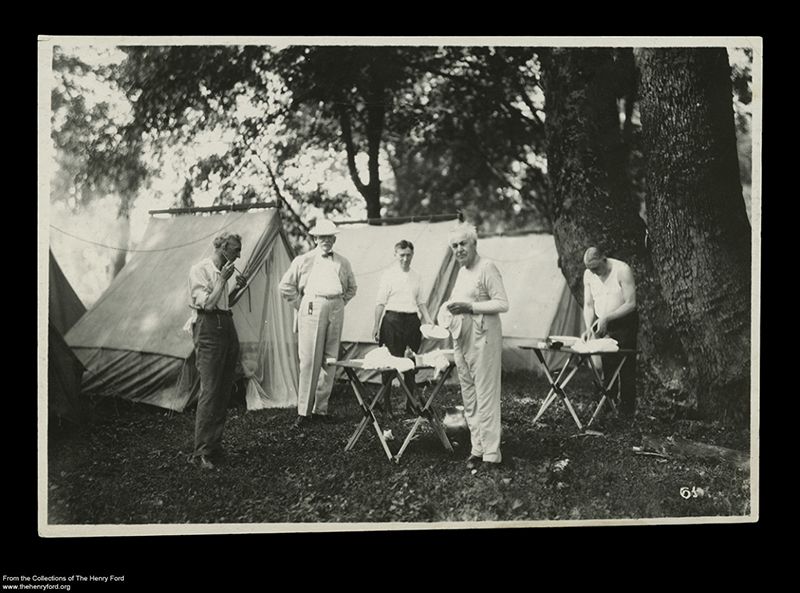

That’s right: gourmet kitchen staff. The Vagabonds’ entourage sometimes included as many as 50 of Ford’s vehicles, heaps of supplies, personal attendants, an official film crew and a truck customized with a refrigerator and gas stove. Burroughs dubbed this mobile kitchen the “Waldorf-Astoria on wheels.” At each stop, support crew erected a communal dinner table—a huge wooden circle with a built-in rotating Lazy Susan. Each man had his own ten-foot-square canvas tent monogrammed with his name and outfitted with a cot and mattress. After sunset, Edison illuminated the campsite with lamps and a generator of his own invention. And what road trip is complete without music? On at least one expedition, the sophisticated travelers toted along a player piano.

“It often seemed to me,” Burroughs observed, “that we were a luxuriously equipped expedition going forth to seek discomfort.”

During their many adventures, the road trippers picked apples for an orchard owner, helped a farmer cradle his crop of oats and hitched a short ride on a passing locomotive. They stopped to inspect mills and waterways. Ford lamented the sight of so many country streams unharnessed, their ever-flowing power going to waste. Edison collected sap-filled plants on the roadside, in hopes of supplying Firestone with alternatives to natural rubber for his tire business.

At night, as the stars slowly rotated overhead, conversation ranged from politics and poetry to the economy and the war in Europe. In 1921, the Vagabonds welcomed one of Firestone’s longtime friends into their ranks: President Warren Harding. The surrounding woods were patrolled by the Secret Service.

The yearly outings afforded the famous friends a chance to unwind—and proved effective advertising for Ford automobiles and Firestone tires. Newspapers across the country ran headlines such as “Millions of Dollars Worth of Brains off on a Vacation” and “Genius to Sleep Under Stars.” People poured into theaters to watch silent movies that Ford’s film crew shot while on the road. Americans discovered the wonders of exploring their own countryside from behind the wheel.

Everywhere the Vagabonds went, they attracted attention. Fans lined the streets of country towns when the caravan passed through. Parades of new automobile owners followed the entourage to the city limits. By 1924, the celebrity campers were too well known to continue. The privacy of their carefree adventures was compromised and the trips ceased. But by that point, the fantasy of the glamorous road trip had come alive in America’s collective imagination.