When Art Fought the Law and the Art Won

The Mapplethorpe obscenity trial changed perceptions of public funding of art and shaped the city of Cincinnati

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/68/60681756-03a2-45b2-9bb0-42c6ac6cef66/image_2.jpg)

Twenty-five years ago, art was put on trial in a highly publicized and political showdown. The Mapplethorpe obscenity trial—the first time a museum was taken to court on criminal charges related to works on display—became one of the most heated battlefronts in the era’s culture wars. Taking place over two weeks in the fall of 1990, the resulting attention challenged perceptions of art, public funding, and what constituted “obscenity.” A quarter century on, the trial’s impact can still be felt, and is being recognized in Cincinnati, the city where it all took place, with a series of events and exhibits.

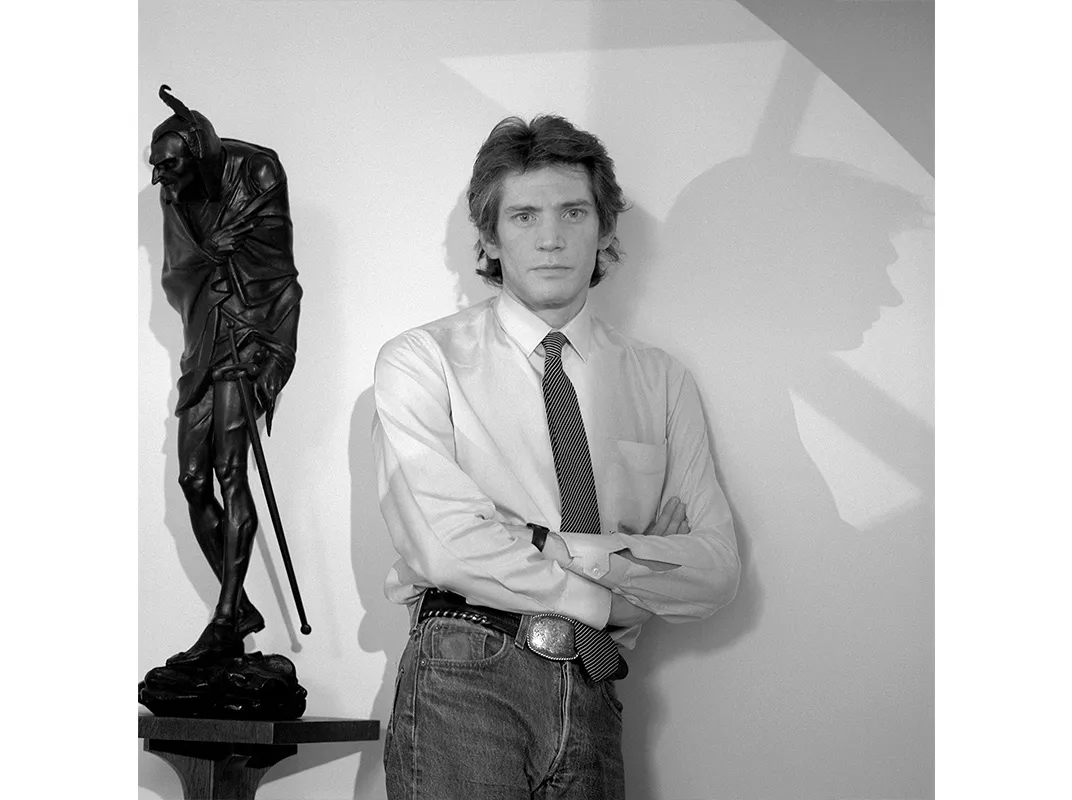

“It sort of never goes away,” says Dennis Barrie, who served as the director of the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) from 1983–1992, and found himself and his institution in the center of a national controversy. “Something will pop up on quite a regular basis about what happened.”

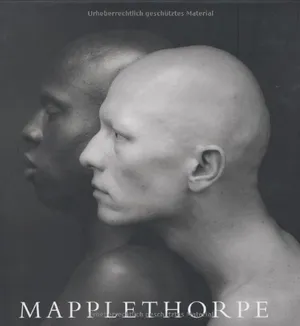

At issue was The Perfect Moment, a retrospective exhibition of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. He had risen to national prominence through his black-and-white depictions of 1970s New York, including celebrities (Andy Warhol, Philip Glass, Deborah Harry), nudes, and graphic depictions of sadomasochism. “Robert sought to elevate aspects of male experience, to imbue homosexuality with mysticism,” as his longtime roommate and occasional collaborator Patti Smith said of his work in her memoir of their relationship, Just Kids. The show’s approximately 175 images captured the range of Mapplethorpe’s subjects over his 25-year career, grouping them into three “portfolios:” nude portraits of African-American men (the “Z” portfolio), flower still lifes (“Y”) and homosexual S&M (“X”).

“The ‘X’ portfolio was tough material for some,” says Raphaela Platow, the museum’s current director.

The show was not for everyone, but Barrie and the CAC board felt its artistic importance could hardly be questioned. The show was especially timely considering Mapplethorpe had died of complications from AIDS just a few months earlier, raising interest in the artist and his portfolio.

The exhibit originally showed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Philadelphia, where it generated some local concerns about a few of the images—particularly some of the more sexually graphic ones, as well as a pair featuring nude children—though generally the show received enthusiastic reviews. But as the survey made its way to Ohio, touring through Chicago and Washington, D.C., controversy began to build.

As Barrie was attending a conference of museum directors several months before The Perfect Moment was scheduled to open in his museum, word arrived that D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery had withdrawn its plan to exhibit Mapplethorpe’s work. The American Family Association, a conservative watchdog group, had been urging politicians to demand that the Corcoran’s National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) funding be eliminated if it went through with the retrospective; its director backed down in the face of pressure.

“That announcement really swept through the room like wildfire,” says Barrie. “All of us who were directors of museums recognized that a door had opened up for hostile censorship against our organizations.”

It was a warning shot for Barrie, and though it might be expected that a museum in Cincinnati would be less likely to draw the kind of attention of one in the nation’s capital, he and the CAC board decided to take precautions. The city was by most measures more conservative than average, prohibiting peep shows, adult bookstores, and strip clubs.

The CAC played offense by lobbying community members for public support for the show, reaching out to politicians and media outlets. They also prepared their defense by securing the services of public relations professionals who had dealt with arts-related controversies in the past, as well as first-amendment lawyer H. Louis Sirkin.

“We really thought at one point that we had won over the city,” says Barrie.

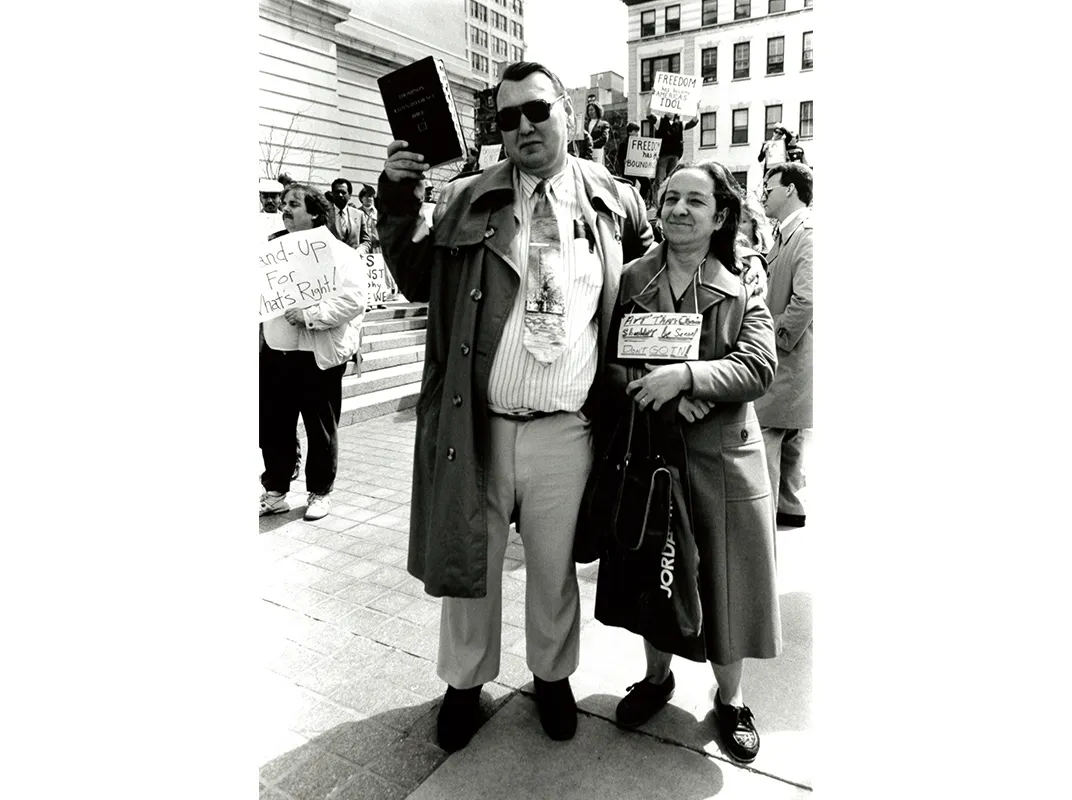

But he underestimated the forces amassing against envelope-pushing works of art, stoked by figures like North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms. Locally, the Citizens for Community Values launched a publicity and letter-writing campaign against the show, calling it “child pornography” and sending thousands of letters demanding the exhibition be cancelled and that funding be pulled from the Fine Arts Fund (an umbrella campaign to raise funds for eight cultural organizations in the city).

“It was a very significant, very well-orchestrated campaign against the exhibition, the Contemporary Arts Center, and the Fine Arts Fund,” says Barrie. “Suddenly a national battle had landed in Cincinnati.”

CAC board chairman Chad P. Wick resigned when local companies threatened to pull business from his employer, Central Trust Co., despite the fact it had no connection to the show. and the city’s law enforcement officials announced that they would personally review the retrospective to see if it violated the law. The pictures I have seen certainly have been criminally obscene,” Hamilton County Sheriff Simon Leis said at the time.

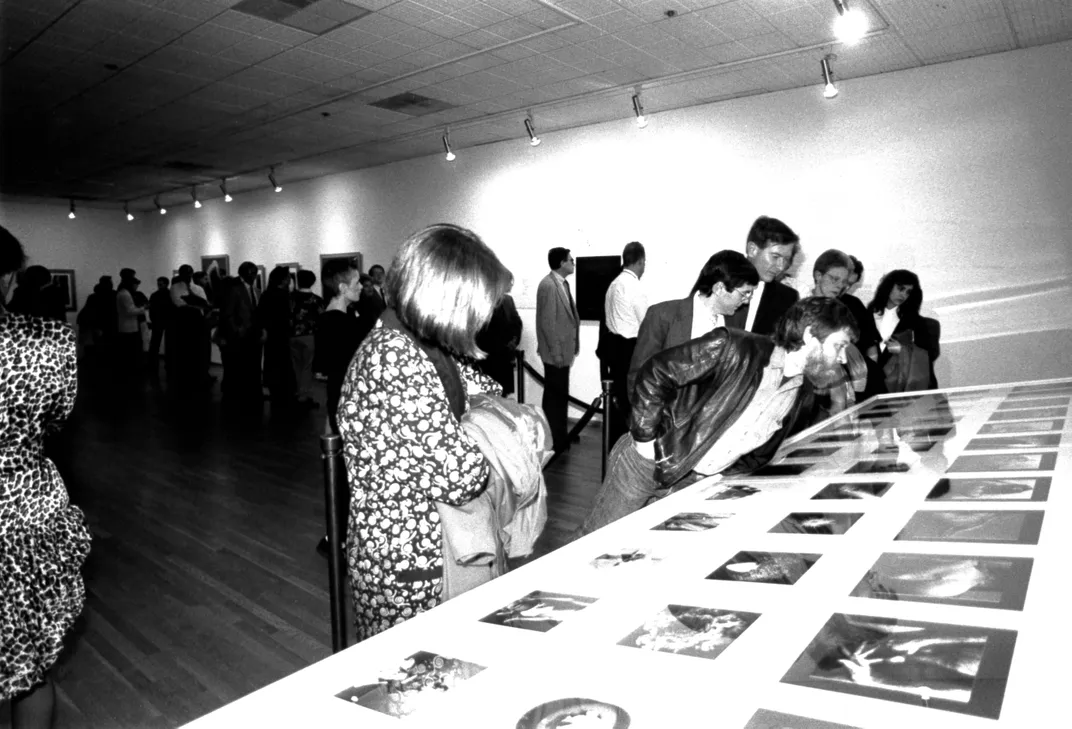

On April 6, the night before the show was scheduled to open to the public, a members preview drew far higher attendance than previous events, with more than 4,000 people in attendance and coverage by local and national media. Besides some protestors, the preview went off peacefully. Barrie was pleasantly surprised.

“I thought we dodged a bullet,” he says. “But it was the next day, when we technically opened to the public, that the vice squad decided to come in.”

A little before noon on opening day, a grand jury issued four criminal indictments—two against the museum and two against Barrie himself for pandering obscenity and illegal use of a minor in nudity oriented materials. Seven of Mapplethorpe’s photos were deemed obscene—two portraits of children and five of explicit male sexual behavior. At about 2:30 p.m., some 20 law enforcement officials entered the museum and presented the CAC officials with the indictments, kicking out the visitors while they videotaped the exhibition to collect evidence.

Outside, hundreds of demonstrators gathered, carrying signs both for and against the display of the work.

“Many of the complaints were made by people who had never seen Mapplethorpe’swork,” says Platow.

“It became like a game of telephone where it grew into something it never was,” adds Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center curator Steven Matijcio, who was just a child when the exhibition opened, and would not fully appreciate the event’s import until studying art at University of Toronto in 1998.

An exception to this “game of telephone” was National Review editor William F. Buckley, one of the show’s most prominent critics who made a point of stopping by the show later in its run to see the photos for himself. “Are we taking the position that any creation executed by an artist is ‘art’—and that it should be immune from criticism?” he asked readers. “Let us suppose that an artist painted a synagogue in the shape of a swastika. Would we be obliged to withhold criticism of the painting, in deference to the liberties of the artist?”

“I went out to talk to him and introduced myself and he said, ‘Oh, I know who you are,’” says Barrie. “He walked through the exhibit with one of our curators and when he came back out I asked, ‘How did you like the exhibition?’ He said, ‘Wonderful exhibition, wonderful. There are only 13 images for which you should go to jail.’”

But no arrests were made on opening day and no photos were seized. It was up to a Cincinnati jury to decide whether or not Barrie and the museum were smut-peddlers.

**********

Fortunately for them, the museum had a lawyer who knew his way around the First Amendment.

H. Louis Sirkin (now senior counsel for Cincinnati-based firm Santen & Hughes) had made a name for himself defending the oft-targeted adult bookstores and video shops in the region, litigating against the Citizens for Community Values a few times before they set their sights on Mapplethorpe.

But Sirkin had never defended a museum against criminal obscenity—nobody had—so this was a new challenge. Usually he would bring in psychologists to argue that adult videos and books were not obscene—that sexual behavior was perfectly normal. But in this case, he set out to argue that art doesn’t have to be pretty, that it might make one uncomfortable and might not be appreciated until much later.

“I wanted to show that this was a really critical time in American history,’” says Sirkin. “You don’t have to like it, you don’t have to come to the museum.”

During evidentiary hearing, Sirkin argued that the prosecution should not be able to present just the seven photos out of the more than 170 shots in the exhibit—that together they composed a body of work that had to be considered as a whole. Just as it would be misguided to judge the merits of a novel based only on a five-page sex scene. But the prosecution prevailed, and the jurors were prohibited from seeing any more than the seven pictures in question.

As the trial began, on September 24, 1990, Sirkin directed his focus to voir dier—the selection of jurors.

“The key to obscenity cases is what you can do in picking the jury,” he says. The prosecution worked to select jurors with little interest in museums, from the outlying parts of the county, and who didn’t seem likely to support the anti-censorship perspective.

The defense anticipated that a jury of conservative Cincinnatians could make it a more difficult case to win. Even as he prepared to take the case to the federal level, Sirkin worked to appeal to the local jurors’ sense of individual freedom. It took four days for the two sides to agree on the jurors.

The prosecution presented the photos in the most salacious way possible while the defense played down the sensationalism and emphasized the images’ artistic value. Sirkin was able to pull from a deep bench of expert witnesses eager to make the case for art—especially art that challenged conventional values and tastes.

“We had our pick of every art director in the country,” says Sirkin, including the heads of museums in Cleveland, Philadelphia and Minneapolis.

After several days of testimony, both sides made their closing arguments and the jury began deliberations on October 5.

They returned after two hours with a verdict: Not guilty on all charges.

Sirkin’s pitch that people should be able to view what they wanted proved as effective as the case for Mapplethorpe’s artistic value. After the trial, Barrie was contacted by three members of the jury, who told him that they were “infuriated that the judge would not let us see all the work.” The prosecution’s campaign to keep the rest of the photos from the jurors had backfired.

The case has left a positive legacy for the CAC, and for Barrie, who went on to help defend offensive song lyrics at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum.

“People see the CAC as a champion of the arts,” says Matijcio. “We’re still always trying to be challenging and topical, to draw on work that’s relevant and of the moment.”

The CAC is honoring the 25th anniversary of the controversy with a symposium, co-presented by biennial art photography show FotoFocus Cincinnati, this October. Barrie, Sirkin, Platow, and officials from other museums will speak on the panel “The Exhibition, The Contemporary Arts Center, and Arts Censorship,” discussing the case and its impact. A second panel will look at “The Artist’s Circle and Studio,” discussing Mapplethorpe’s work and approach to his art, while “Curators Curate Mapplethorpe” will gather curators from the J. Paul Getty Museum, FotoFocus, and elsewhere in a discussion.

The anniversary is also being recognized artistically, with the opening on November 6 of After the Moment: Reflections on Robert Mapplethorpe. The show includes guest curators who are showing a number of works inspired by the original Mapplethorpe retrospective, including a subsection of images from photographers connected with the Images Center for Photography at around the time of the trial, whose own shows were cancelled or impacted by the controversy.

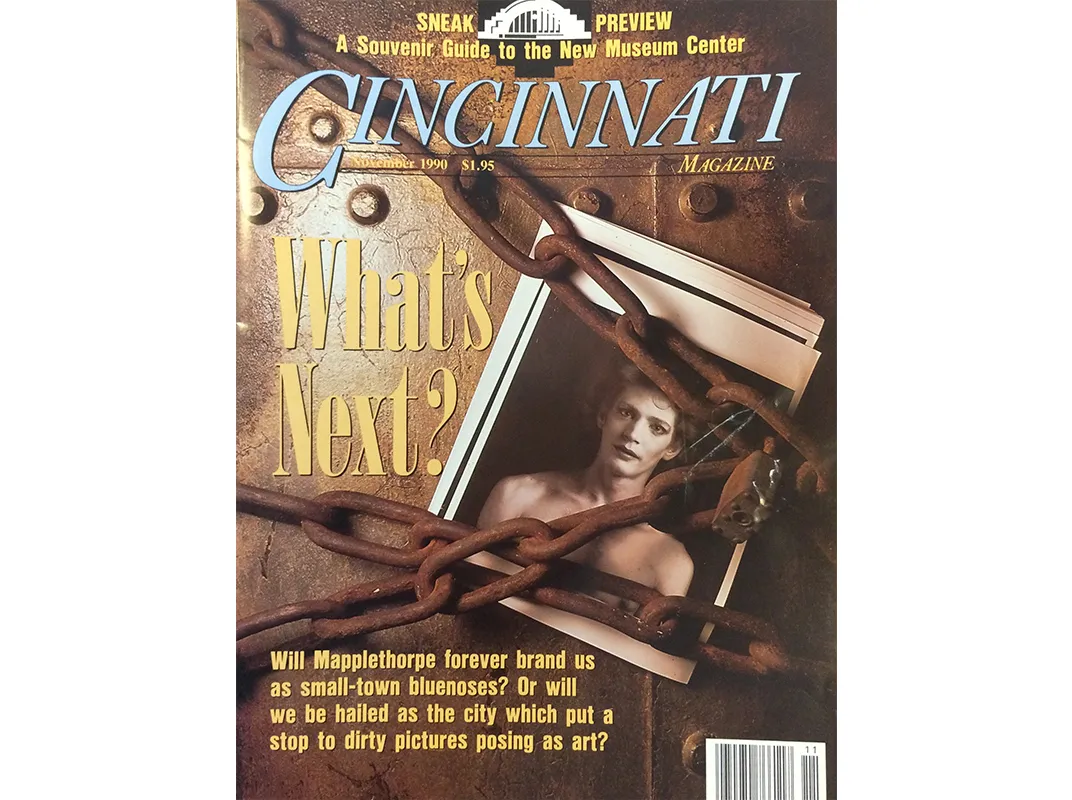

Cincinnati itself, at the time seen as outright hostile towards the arts, has also grown into an unlikely advocate for the arts. ArtWorks, an ambitious public-arts campaign, has erected dozens of murals by local artists throughout the city, launched an initiative posting reproductions of classic pieces from the Art Museum of Cincinnati all around town.. Rather than shying away from controversial issues, the city’s museums are addressing them in shows such as drawn at the University of Cincinnati’s Philip M. Meyers Jr. Memorial Gallery, addressing the police shooting of Samuel DuBose. While the editors of Cincinnati Magazine once fretted that the Mapplethorpe controversy might “forever brand us as small-town bluenoses,” the city continues working to change this perception.

While the cultural battle lines have shifted compared to a quarter century ago, Matijcio emphasizes that some things still have not changed: the power of Mapplethorpe’s work.

“Those photos are still challenging,” he says. “They continue to reverberate.”

Mapplethorpe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)