When the British Wanted to Camouflage Their Warships, They Made Them Dazzle

In order to stop the carnage wrought by German U-Boats, the Allied powers went way outside the box

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/85/74852b88-6ff2-42d0-9add-caff6075cb8c/hms_kildangan_iwm_q_043387.jpg)

In late October 1917, King George V spent an afternoon inspecting a new division of Britain’s merchant naval service, the intriguingly named “Dazzle Section”.

The visit came during one of the worst periods in war that had already battered British sea power. German U-boat technology was a devastating success; fully one-fifth of Britain’s merchant ships, ferrying supplies to the British Isles, had been sunk by the end of 1916. The next year brought fresh horror: Desperate to grind down the Allies and bring an end to this costly war, the Kaiser declared unrestricted submarine warfare on January 31, 1917, promising to torpedo any ship that came within the warzone. Imperial U-boats made good on that promise – on April 17, 1917 a U-boat torpedoed a hospital ship, the HMHS Lanfranc, in the English Channel, killing 40 people, including 18 wounded German soldiers. “Hun Savagery” read the headlines. The Lanfranc’s sinking was outrageous, but it was by no means the only one – between March and December 1917, British ships of all kinds were blown out of the water at a rate of 23 a week, 925 ships by the end of that period.

So it was imperative that what George V was about to see worked.

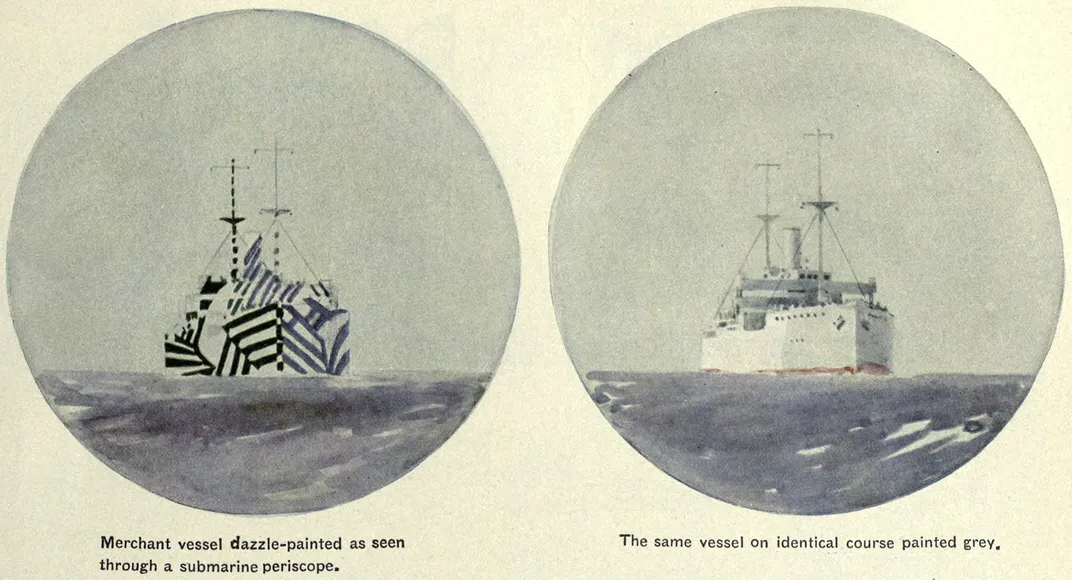

The King was shown a tiny model ship, painted not standard battleship gray, but in an explosion of dissonant stripes and swoops of contrasting colors. The model was mounted on a turntable set against a seascape backdrop. George was then asked to estimate the ship’s course, based on his observations from a periscope fixed about 10 feet away. The King had served in the Royal Navy before the death of his older brother put him first in line for the throne, and he knew what he was doing. “South by west,” was his answer.

“East-southeast” came the answer from Norman Wilkinson, head of the new department. George V was astounded, dazzled even. “I have been a professional sailor for many years,” the confounded King reportedly said, “and I would not have believed I could have been so deceived in my estimate.”

Dazzle, it seems, was a success.

How to camouflage ships at sea was one of the big questions of World War I. From the early stages of the war, artists, naturalists and inventors showered the offices of the United States Navy and the British Royal Navy with largely impractical suggestions on making ships invisible: Cover them in mirrors, disguise them as giant whales, drape them in canvas to make them look like clouds. Eminent inventor Thomas Edison’s scheme of making a ship appear like an island – with trees, even – was actually put into practice. The S.S. Ockenfels, however, only made it as far as New York Harbor before everyone realized what a bad and impractical idea it was when part of the disguise, a canvas covering, blew away. Though protective coloring and covers worked on land, the sea was a vastly different environment. Ships moved through changing light and visibility, they were subject to extreme weather, they belched black smoke and bled rust. Any sort of camouflage would have to work in variable and challenging conditions.

Wilkinson’s innovation, what would be called “dazzle,” was that rather than using camouflage to hide the vessel, he used it to hide the vessel’s intention. Later he’d say that he’d realized that, “Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer – in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as the course on which she was heading.”

In order for a U-boat gunner to fire and hit his target from as far as 1,900 meters away (and not closer than 300 meters, as torpedoes required at least that much running distance to arm), he had to accurately predict where the target would be based on informed guesses. Compounding the difficulty was the fact that he had typically less than 30 seconds to sight the target ship through the periscope, or risk the periscope’s wake being seen and giving away the submarine’s location. Typical U-boats could only carry 12 very expensive and very slow torpedoes at a time, so the gunner had to get it right the first time.

“If you’re hunting for ducks, right, all you have to do is lead the target and it’s a simple process. But if you’re a submarine aiming at a ship, you have to calculate how fast a ship is going, where is it going, and aim the torpedo so that they both get to the same spot at the same time,” says Roy Behrens, a professor at the University of Northern Iowa, author of several books on Dazzle camouflage and the writer behind the camouflage resource blog Camoupedia. Wilkinson’s idea was to “dazzle” the gunner so that he would either be unable to take the shot with any confidence or spoil it if he did. “Wilkinson said you had to only be 8 to 10 degrees off for the torpedo to miss. And even if it were hit, if [the torpedo] didn’t hit the most vital part, that would be better than being hit directly.”

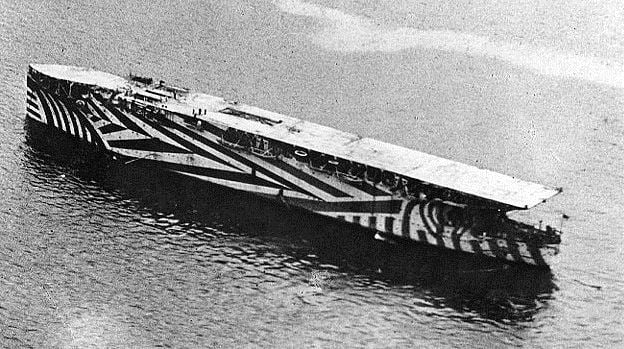

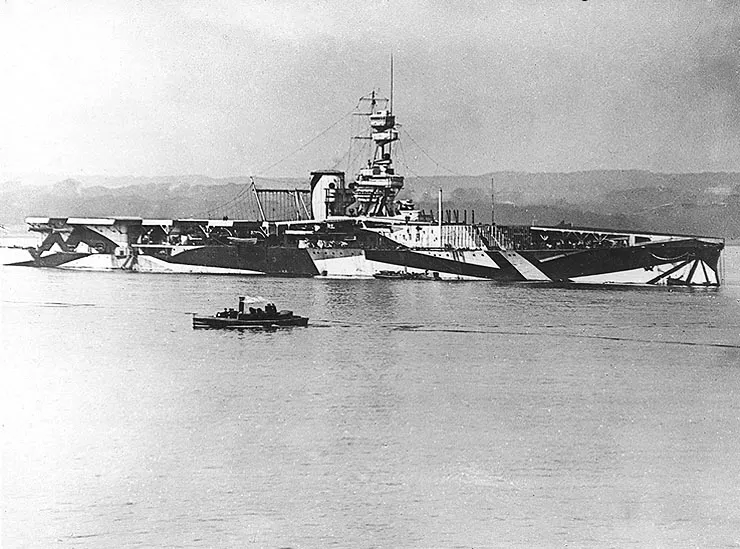

Wilkinson used broad swathes of contrasting colors—black and white, green and mauve, orange and blue—in geometric shapes and curves to make it difficult to determine the ship’s actual shape, size and direction. Curves painted across the side of the ship could create a false bow wave, for example, making the ship seem smaller or imply that it was heading in a different direction: Patterns disrupting the line of the bow or stern made it hard to tell which was the front or back, where the ship actually ended, or even whether it was one vessel or two; and angled stripes on the smokestacks could make the ship seem as if it was facing in the opposite direction. One American dazzle camoufleur (the actual term for a camouflage artist) referred to the optical distortion concept undergirding Dazzle as “reverse perspective”, also known as forced perspective and accelerated perspective, optical illusions that create a disconnect between what the viewer perceives and what is really happening (think of all those photos of tourists holding up the Leaning Tower of Pisa). In practice, that meant that the system did have its limitations – it could only be applied to ships that would be targeted by periscopes, because it worked best when seen from the low-down viewpoint of a U-boat gunner.

Dazzle Camouflage from Joe Myers on Vimeo.

“It’s counterintuitive. People can’t really believe that you could interfere with the visibility of something by making it more highly visible, but they don’t understand how the human eye works, that something needs to stand out from the background and hold together as an integral figure,” says Behrens.

Wilkinson was, in some ways, an unlikely innovator. At 38, he was known as talented painter of landscapes and maritime scenes – his painting of Portsmouth Harbour went down in the smoking rooms of the Titanic. Nothing in his work augers the kind of modern, avant garde aesthetic that Dazzle possessed. But crucially, Wilkinson had both an understanding of perspective and a relationship with the Admiralty and merchant shipping authorities. An enthusiastic yacht racer, he’d joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserves at the outbreak of war. In 1917, he was a lieutenant in command of an 83-foot patrol launch that swept the central English Channel for mines, according to Nicholas Rankin in his book, A Genius For Deception: How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars. And where other innovators, including John Graham Kerr, a Scottish naturalist whose similar camouflage ideas were used briefly and discarded by the Royal Navy, failed, Wilkinson’s straightforward charisma helped his rather outré idea be taken seriously by important people, wrote Peter Forbes in Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage.

After earning support for the idea, Wilkinson was given the chance to test his theory in the water. The first ship to be dazzled was a small store ship called the HMS Industry; when it was launched in May 1917, coastguards and other ships sailing the British coast were asked to report their observations of the vessel when they encountered it. Enough observers were sufficiently confused that by the beginning of October 1917, the Admiralty asked Wilkinson to dazzle 50 troopships.

Though the new initiative had backing from both the Merchant Navy and the Royal Navy, it was still operating on a wartime budget. The Royal Academy of Arts offered up four unused studios for headquarters and Wilkinson went to work with a team of 19– five artists, three model makers, and 11 female art students who hand-colored the technical plans for the final designs (one later became Wilkinson’s wife). Each design not only had to be unique to prevent U-boat crews from getting used to them, but they also had to be tailored to individual ships. Wilkinson and his artists designed schemes first on paper, and then painted them on tiny, rough-hewn wooden models, which they’d place in the mock seascape George V saw. The models were examined through periscopes in various lighting. Designs were chosen for “maximum distortion”, Wilkinson later wrote, and handed off to the art students to map out on technical drafts, to be then executed by ship painters on ships in dry dock. By June 1918, less than a year after the division was created, some 2,300 British ships were dazzled, a number that would swell to more than 4,000 by the end of the war.

The United States, which joined the war on April 6, 1917, was then grappling with as many as six systems of camouflage, most of which peddled low visibility or invisibility to private ship owners. The Navy, however, had little confidence in the claims of diminished visibility and moreover, was also dealing with the fact that many of its ships had been German ships – meaning that the enemy knew their speed and vulnerabilities. When news of the dazzle system and its ability to mask the speed and kind of ships reached Britain’s new ally, a young Franklin Roosevelt, then assistant to the secretary of the navy, agreed to meet with Wilkinson to discuss it. After another successful demonstration of dazzle, in which a confused U.S. admiral reportedly exploded, “How the hell do you expect me to estimate the course of a God-damn thing all painted up like that?”, Wilkinson was asked to help set up an American dazzle department under the Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair. Wilkinson spent five weeks in the U.S., with Everett Warner, an artist and Naval Reserve officer who would head up the Washington, D.C. dazzle subsection, as his host. Chummy as that sounds, it wasn’t.

“There was a lot of fighting or jealousy or whatever between the U.K. and the U.S.,” says Behrens with a chuckle. “If you go to the correspondence, you find that the American artists are making fun of [Wilkinson] and all sort of that thing. Warner arrived at the idea that Wilkinson didn’t know what he was doing and that what he was doing was quite haphazard.”

However the British and American departments felt about each other, they were still creating visually disruptive designs that on the face of it, were very much alike: Broad stripes and curves of white, black, green, blue, spiky and jagged and very Modern art. This was not lost on contemporary journalists, who branded the dazzled ships a “futurist’s bad dream” and “floating Cubist paintings”, as well as “an intoxicated snake”, “a Russian toyshop gone mad”, and a “cross between a boiler explosion and a railroad accident”. That dazzle bore such a similarity to burgeoning movements in art wasn’t lost on the artists, either – Picasso even claimed that Dazzle was actually his idea.

But Modern art, which had been introduced in America at the 1913 Armory Show, was an object of derision and suspicion for contemporary newspapers. “Very frequently in newspapers and magazines, they were trying to explain it to the public and I think [the public] had great difficulty believing it was legitimate,” says Behrens. “But on the other hand, that’s why it was fascinating.” This amusement and fascination in equal measure reflected how the public saw dazzle. It was lampooned in newspaper cartoons, of course – one image shows painters tarring a road in dazzle patterns – but its distinctive look also popped up on bathing suits and dresses, cars and window displays. “Dazzle balls”, for which attendees dressed in dazzle-inspired costumes, gained popularity as ways to raise money for the war effort.

Still, convincing Naval personnel dazzle was more than just fun was difficult. “I had a large of collection of [correspondence from] experienced Navy officers and ship captains making fun of it. It made them sick that their pristine ship was painted with all these Jezebel patterns,” says Behrens, noting that the idea of these flashy ships seemed to subvert their sense of military order. The ships were so wild that some American observers started calling them “jazz” ships, after the improvisational style of popular contemporary music. But Warner, who applied a scientific rigor to understanding how his designs worked, rejected that comparison. Dazzle was, he said, “firmly grounded in the book of Euclid” on geometric principles of visual disruption and proportion, and was not the work of a “group of crazy Cubists”, Behrens recounted in his book, False Colors.

However founded on science it was, determining whether Dazzle actually worked is difficult. In theory, it should work: Behrens found that in 1919, near the end of the war, an MIT engineering student studied the efficacy of individual designs using one of the original model observation theaters provided by the Navy. Three sets of observers were given the same test that George V and the unnamed American naval commander failed. Designs that yielded a higher degree of course error were considered successful; the most successful were off by as much as 58 degrees, when just 10 degrees would be sufficient for a fired torpedo to miss its target. Similarly, in 2011, researchers from the University of Bristol determined that dazzle patterns could disrupt an observer’s perception of the speed of a moving target, and could even have a place on modern battlefields.

But lab conditions are hardly real life. Forbes, in his book, writes that the Admiralty commissioned a report on dazzled ships that came out in September 1918. The statistics were less than conclusive: In the first quarter of 1918, for example, 72 percent of dazzled ships that were attacked were sunk or damaged versus 62 percent of non-dazzled, implying that dazzle did not minimize torpedo damage.

In the second quarter, the statistics reversed themselves: 60 percent of attacks on dazzled ships ended in sinking or damage, compared to 68 percent of non-dazzled. More dazzled than non-dazzled ships were being attacked in the same period, 1.47 percent versus 1.2 percent, but fewer of the dazzled ships were sunk when hit. The Admiralty concluded that though dazzle probably didn’t hurt, it also probably wasn’t helping. American dazzled ships fared better – of the 1,256 ships dazzled between March 1 and November 11, 1918, both merchant and Naval, only 18 were sunk – perhaps owing to the different seas in which American ships were sailing. Ultimately, Behrens said it’s difficult to retroactively determine whether dazzle was truly a success, noting, “I don’t think it will ever be clear.”

And in truth, it didn’t matter whether dazzle actually worked or not: Insurance companies thought it did and therefore lowered premiums on dazzled ships. At the same time, the Admiralty’s investigation into dazzle noted that even if it didn’t work, morale on dazzled ships was higher than on non-dazzled and that was reason alone to keep it.

By November 1918, however, the war was over, though the battle between Wilkinson and the Scottish naturalist Kerr over who actually invented dazzle was just heating up. Kerr argued that he’d introduced the Admiralty to a similar idea back in 1914 and demanded recognition. The Admiralty eventually sided with Wilkinson and awarded him £2,000 for dazzle; for years after, however, Kerr never gave up the idea that he’d been cheated and the two men would trade snide comments through the next war. But exactly what they were fighting over was soon forgotten. Ships require frequent painting – it’s part of what keeps them preserved – so the Allied vessels lost their dazzled coating under a more sober gray. Though World War II saw a resurgence of dazzle in an effort to hide a ship’s class and make, its use was limited and dazzle’s legacy was again buried under layers of maritime paint.

Sort of. Because though dazzle’s influence on naval warfare may have been short-lived, its impact on art and culture remains significant even now. Dazzle, though functional in its intent, was also part of a wave of Futurism, cubism, expressionism, and abstract art that eroded the centuries of representational art’s dominance. The look of dazzle later re-emerged in 1960s Op-art, which employed similar techniques of perspective and optical illusion, and in the mass market fashion that followed. Even today, dazzle remains fashionable, recalled in the aggressive patterns of designers like Jonathan Saunders, or more directly referenced in the “Urban Dazzle” collection of French sportswear designer Lacoste, the Dazzle rainboots from Hunter, and upscale British handbag label Mulberry’s Dazzle collection.

“Dazzle is just everywhere, it’s such a successful visual design system. It’s hugely attractive… I think it’s been used – plundered as it were – but used as a kind of inspiration certainly in fashion,” notes Jenny Waldman, director of 14-18 Now, an ambitious arts program working in partnership with the Imperial War Museum, the British government, and U.K. arts organizations to commemorate the centenary of the World War I. Dazzle was everywhere but on ships – even if the designs themselves weren’t forgotten, the link between them and the war was. “There are a lot of great untold stories, and the dazzle ship is a kind of whopping great untold story,” says Waldman.

That changed, however, when in 2014, 14-18 Now called on contemporary artists to dazzle real-life vessels. Explains Waldman, “The brief was very much to be inspired by the dazzle ships rather then try to recreate the Dazzle designs or functionality in any way.”

Finding artists, Waldman says, was easier than finding ships, but they eventually managed to locate three. The Snowdrop, designed by Sir Peter Blake, the artist who created the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, is actually a working ferry on the River Mersey in Liverpool and will be operational through December 2016. The other two ships recently finished their deployment: The Edmund Gardner, an historic pilot ship in drydock outside the Mersey Maritime Museum in Liverpool, was painted in green, orange, and black stripes by Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez and the HMS President, which is permanently docked on the River Thames, was dazzled in grey, black, white and orange by artist Tobias Rehberger. The President is one of only three surviving Royal Navy ships that served in the First World War; called the HMS Saxifrage when it was built in 1918, it was actually dazzled by Wilkinson and his team during its tour of duty.

So far, more than 13.5 million people have seen, visited, or sailed on the dazzled ships and 14-18 Now recently announced that a fourth ship, the MV Fingal, a former lighthouse tender docked at the Port of Leith in Edinburgh, will be dazzled by Scottish artist Ciara Phillips. The ship will be unveiled in late May, in time for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

“The wonderful thing about our ships is that they are very big and they’re very public, and the Mersey ferry you can go on, it makes them hugely accessible,” says Waldman. The fact that they show very well on social media has helped to spread the story of the dazzle ships. The ships also speak, as Waldman says, to “the power of contemporary art to reveal and explore the unknown stories of the First World War.” Waldman continued, “People see the dazzle ferry and they think, ‘I want to go on that, that looks phenomenal’ and when they’re on it, they find out more. And then they tell their friends and 13-and-a-half million people now know about the dazzle ships.”

So perhaps this time, the story of the dazzle ships and their place in the science and art of making war won’t be forgotten.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)