When Churchill Dissed America

Our exclusive first look at the diaries of King George VI reveals the Prime Minister’s secret hostility to the United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/c0/50c0e858-5845-432b-9ca1-2a1b0db40bd3/churchill-letterbox-web-v2.jpg)

The gift of a common tongue is a priceless inheritance and it may well someday become the foundation of a common citizenship,” Winston Churchill prophesied in his famous speech at Harvard University on Monday, September 6, 1943. “I like to think of British and Americans moving about freely over each other’s wide estates with hardly a sense of being foreigners to one another.” His mother having been born in Brooklyn of American parentage, Churchill believed that he personified what he later called the “special relationship” between the United Kingdom and the United States. It was long a theme of his: He had been making speeches on the subject of Anglo-American unity of action since 1900, and in 1932 had signed a contract for his book A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, which emphasized the same thing.

“If we are together nothing is impossible,” he continued that day in 1943. “If we are divided all will fail. I therefore preach continually the doctrine of the fraternal association of our two peoples...for the sake of service to Mankind.” He proclaimed that doctrine for the rest of his life—indeed, on the day he resigned the premiership in April 1955 he told his cabinet, “Never be separated from the Americans.” Throughout a political career that spanned two-thirds of a century, Churchill never once publicly criticized the United States or the American people. In all of his 16 visits to the United States between 1895 and 1961, with eight as prime minister and almost half of them after 1945, he studiously confined himself to public expressions of support and approbation.

Yet as I discovered while writing my new biography, Winston Churchill: Walking With Destiny, he often took a very different stance in private. From a variety of new sources—including the wartime diaries of King George VI in the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, opened to me by the gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen—it is clear that Churchill regularly expressed searing criticism of the United States, and especially the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. The newly published diaries of Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London from 1932 to 1943; verbatim War Cabinet records that I discovered at the Churchill Archives; and the papers of Churchill’s family, to which I have been given privileged access, all provide confirmation.

As the first Churchill biographer to be allowed to research the king’s unexpurgated wartime diaries, I was surprised at the depth of ire that Churchill sometimes directed toward Britain’s greatest ally, indeed in many ways Britain’s savior. Much can be put down to the frustration he naturally felt toward American military nonintervention in Europe until after Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, but there was a good deal of anti-American venting thereafter, too. Churchill’s relationship with his mother country was much more complex than the Harvard speech and the rest of his public stance implied.

Although he had enjoyed his first trip to the United States in 1895, at age 20, Churchill’s initial attitude toward Anglo-American unity was sarcastic, bordering on the facetious. When his mother, the socialite Jennie Jerome, proposed publishing a magazine dedicated to promoting that idea in March 1899, he wrote from Calcutta, where he was serving as a junior cavalry officer, that the motto she wanted to adopt—“Blood is thicker than water”—had “long ago been relegated to the pothouse Music Hall.” He sneered at her concept of printing the Union Jack crossed with the Stars and Stripes on the front cover as “cheap” and told her that the “popular idea of the Anglo American alliance—that wild impossibility—will find no room among the literary ventures of the day.”

From the beginning, his attitude was one of clear-eyed, unsentimental realpolitik. “One of the principles of my politics,” he told his mother in 1898, “will always be to promote the good understanding between the English-speaking communities....As long as the interests of two nations coincide as far as they coincide they are and will be allies. But when they diverge they will cease to be allies.”

Churchill fully appreciated the United States’ entry into World War I in April 1917. “There is no need to exaggerate the material assistance,” he wrote in his book The World Crisis, but “the moral consequence of the United States joining the Allies was indeed the deciding cause in the conflict.” Without America, the war “would have ended in a peace by negotiation, or, in other words, a German victory.”

In the 1920s, Churchill was highly critical of the United States’ determination to build a fleet equal in power and tonnage to the Royal Navy’s. “There can really be no parity between a power whose navy is its life and a power whose navy is only for prestige,” he wrote in a secret cabinet memorandum in June 1927, while he was chancellor of the exchequer. “It always seems to be assumed that it is our duty to humour the United States and minister to their vanity. They do nothing for us in return but exact their last pound of flesh.” The next month he went much further, writing that although it was “quite right in the interests of peace” to say that war with the United States was “unthinkable,” in fact “everyone knows this is not true.” For, however “foolish and disastrous such a war would be, we do not wish to put ourselves in the power of the United States....Evidently on the basis of American naval superiority, speciously disguised as parity, immense dangers overhang the future of the world.” The next year, speaking after dinner to the Conservative politician James Scrymgeour-Wedderburn at Churchill’s country house, Chartwell Manor in Kent, he said that the U.S. was “arrogant, fundamentally hostile to us, and that they wish to dominate world politics.”

Herbert Hoover’s election to the presidency in November 1928 made matters worse, because of his tough stance on British repayment of war debts and the effect that had on the economy, which Churchill was still stewarding as chancellor of the exchequer. “Poor old England,” he wrote to his wife, Clementine. “She is being slowly but surely forced into the shade.” Clementine wrote back to say that he should become foreign secretary, “But I am afraid your known hostility to America might stand in the way. You would have to try and understand and master America and make her like you.” But his hostility to America was not known beyond the cognoscenti inside government, as he assiduously kept it out of his many speeches.

The outbreak of World War II naturally intensified Churchill’s determination to allow no word of public criticism to drop from his lips, especially of Roosevelt. “Considering the soothing words he always uses to America,” noted his private secretary, Jock Colville, nine days after Churchill became prime minister in May 1940, “and in particular to the President, I was somewhat taken aback when he said to me, ‘Here’s a telegram for those bloody Yankees. Send it off tonight.’” During the Battle of Britain, Churchill said the Americans’ “morale was very good—in applauding the valiant deeds done by others!” A week before Roosevelt was re-elected in November 1940, Colville recorded in his diary that Churchill said he “quite understood the exasperation which so many English people feel with the American attitude of criticism combined with ineffective assistance; but we must be patient and we must conceal our irritation.”

Any hope Churchill had that Roosevelt’s electoral victory might bring the United States into the war against the Nazis had evaporated by New Year’s Day 1941, when Britain faced bankruptcy because it had to pay cash for all the munitions and food it was buying from the United States. Churchill told Colville, “The Americans’ love of doing good business may lead them to denude us of all our realisable resources before they show any inclination to be the Good Samaritan.”

As well as expressing these criticisms to his private secretary and to some cabinet colleagues, Churchill also told the monarch what he really thought of Roosevelt and the Americans. His relations with King George VI were not initially good when he became prime minister, largely because Churchill had supported the king’s elder brother Edward VIII (later the Duke of Windsor) during the abdication crisis four years earlier. But during the months of the Fall of France, the Battle of Britain and the London Blitz they swiftly improved, and by 1941 Churchill was confiding in the king at their private lunches at Buckingham Palace every Tuesday. They served themselves from a sideboard so that no servants need be present, and after each meeting the king wrote in his diary what Churchill had told him.

His diary is held in the Royal Archives at the top of the Round Tower at Windsor Castle. The tower’s origins may be traced to the 11th century, soon after the Norman Conquest, but King George IV added the top floor in the early 19th century. Because there are no elevators, every trip to the summit involves a mini-workout, which is rewarded by magnificent views of Berkshire and the surrounding counties. But I had little time to gaze out the window as I made the most of my extraordinary opportunity to examine King George VI’s diary, which I was allowed to do one blue-leather-bound volume at a time, and under constant oversight, even on trips to the lavatory (though the staff, even while providing such eagle-eyed supervision, was unfailingly able and friendly).

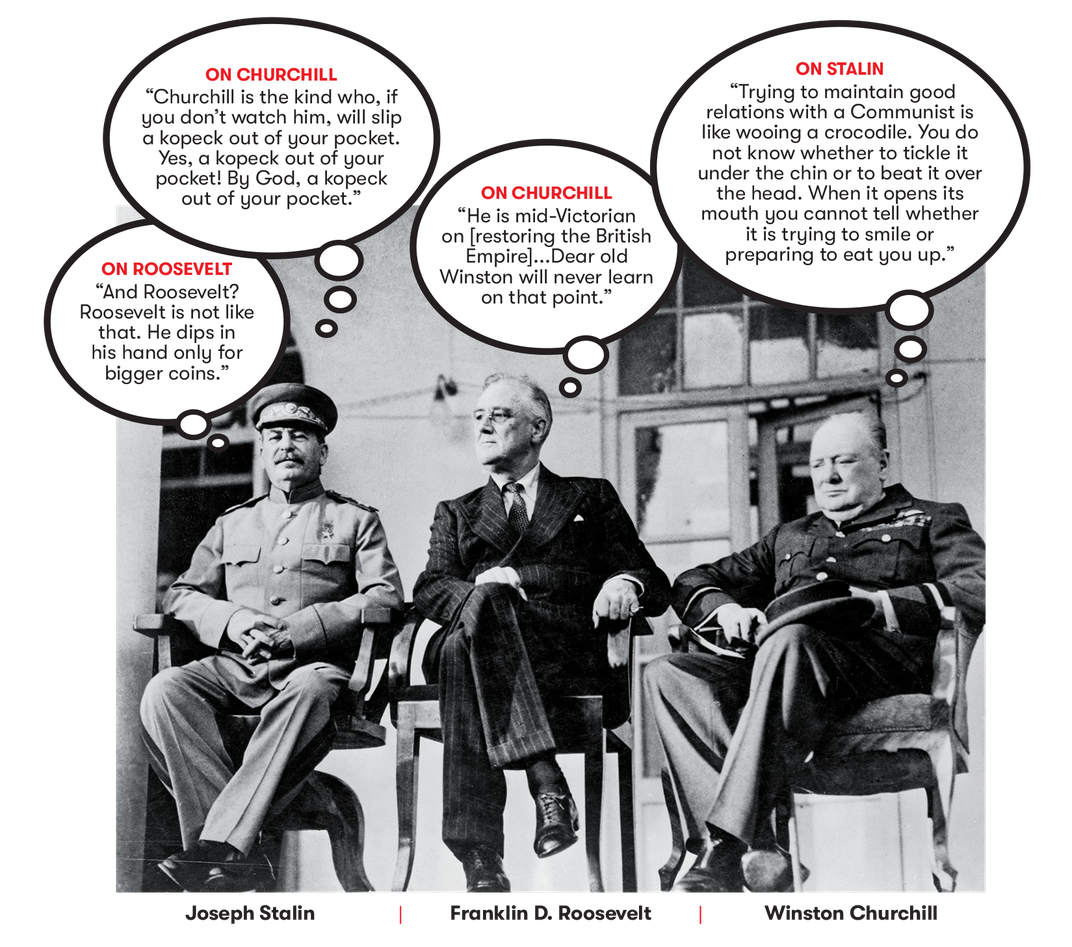

“The Americans are all talk and do nothing while Japan lands fresh forces in Sumatra, Sarawak and elsewhere,” the prime minister complained to the king soon after Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941. A month later he insensitively added, of the dangers of a Japanese invasion of Australia, “The U.S. fleet would have prevented this from happening had her fleet been on the high seas instead of at the bottom of Pearl Harbour.” That April, as the Japanese Navy threatened Allied shipping in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, he said, “We are in a hole, and the USA fleet is in San Francisco doing nothing to help.” On New Year’s Day 1943, Churchill said of future Allied strategy, “We have to collaborate with the Americans over these matters as we cannot do them without their help. They are so slow in training their army and getting it over here.”

Churchill was clearly jealous of the leading position the Americans had assumed through their vastly superior production of war materiel by the spring of 1943. “Winston is keen on an Imperial Conference,” the king noted that April, “so as to discuss the question of putting up a united British Commonwealth and Empire front to show the world and USA that we are one unity. The Americans are always saying they are going to lead the postwar world.” A week later the prime minister expressed his (completely unfounded) suspicions that the “USA really wants to fight Japan and not Germany or Italy.” By October he was insisting, “The USA cannot have Supreme Commanders both here and in the Mediterranean and we must not allow it. The Med is our affair and we have won the campaigns there.” That was not true, either, as the king must have known. The U.S. Army fully shared the trials of the Italian campaign from the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 onward, and indeed it was the American general Mark Clark who was the first to enter Rome, on June 5, 1944.

In March 1944, Churchill likened the strategic situation in Europe to “a Bear drunken with victory in the east, and an Elephant lurching about in the West, [while] we the UK were like a donkey in between them which was the only one who knew the way home.” By July 4, nearly a month after D-Day, he was reporting to the king that, over his pleas to Roosevelt to fight in the Balkans rather than the South of France, “He was definitely annoyed at FDR’s reply, and put out that all our well thought-out plans had been ignored by him and [the U.S. Joint] Chiefs of Staff.” A month later he worried that with Gens. George S. Patton and Omar Bradley advancing faster in Germany than Gen. Bernard Montgomery, “The two Americans may want to separate their army from ours which would be very stupid.”

Yet there was not a whisper of this antipathy in Churchill’s telegrams to the Americans, let alone in his public references in the Commons and his broadcasts to his allies. He ripped up many bad-tempered telegrams to Roosevelt before sending much more temperate ones. In particular he kept private his resentment that the Americans did not support taking a tougher stance against the Soviet Union over Polish integrity and independence after the Yalta Conference of February 1945. “Winston was not satisfied with FDR’s reply to his telegram re Poland,” the king noted on March 13. “It was much too weak and the Russians want to be told matters strongly.”

The next month, Churchill told Clementine, “Undoubtedly I feel much pain when I see our armies so much smaller than theirs. It has always been my wish to keep equal, but how can you do that against so mighty a nation with a population nearly three times your own?”

It was impossible. But while Churchill is often accused of appeasing the United States, in fact he promoted Anglo-American unity because it served Britain’s best interests. His public reticence to criticize the United States reflected two aspects of his character that were often to the fore throughout his political career. The first was his capacity ruthlessly to sacrifice the trivial and the short-term for the greater prize. The second was his powerful sense of personal and national destiny. He foresaw a time when Britain would need the United States desperately.