When Don the Talking Dog Took the Nation by Storm

Although he ‘spoke’ German, the vaudevillian canine captured the heart of the nation

:focal(632x228:633x229)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/9d/089d4192-f858-4c6a-a932-7037a2548cbd/don-talking-dog.jpg)

In the heyday of American vaudeville—roughly 1880 to 1930—few shows were complete without an animal act or two.

Rats in little jockey costumes rode cats around racetracks. Elephants waltzed and danced the hula. Kangaroos boxed, sea lions juggled, monkeys pedaled bicycles and smoked cigarettes.

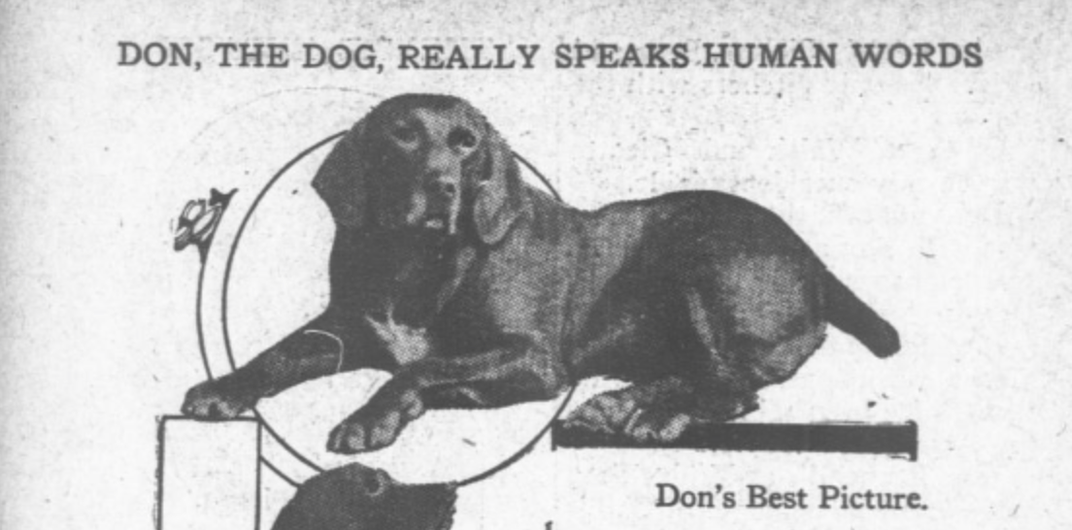

But no animal act seemed to get as much notice as Don the Talking Dog, a sensation from the moment he debuted in 1912. Variously described a German hunting dog, forest dog, setter, or pointer, the 8-year-old Don was acclaimed as “the canine phenomenon of the century.”

With a vocabulary that ultimately reached eight words—all in German—Don had garnered attention in the United States as early as 1910, with breathless newspaper reports from Europe. According to some accounts, his first word was haben(“have” in English), followed by “Don,” kuchen(“cake”), and hunger (same word in English and German).

Theoretically, this allowed him to form the useful sentence: Don hunger, have cake—although most accounts say he typically spoke just one word at a time, and only when prompted by questions. He later added ja and nein (“yes” and “no”), as well as ruhe (“quiet” or “rest”) and “Haberland” (the name of his owner).

Vaudeville was designed as family entertainment suitable for all ages. While less prestigious than “legitimate” theater (think Hamlet), it was a considerable step up from its competitor, burlesque, which tended to be more risqué (think scantily clad dancing girls.) It also catered to Americans of all socioeconomic groups, from the well-established middle class to freshly arrived immigrants—basically anybody with the 25 cents to $1.50 it cost to buy a ticket.

Though centered on Broadway and other prime locations around Manhattan, with lavish theaters that could seat several thousand patrons, vaudeville also flourished in cities large and small across the U.S. Performers would go on a “circuit” from city to city, often starting in New York, gradually making their way to the west coast, and then looping back again. Some acts would also travel to England, continental Europe, Australia and South Africa, where vaudeville (sometimes called “variety”) was popular, as well.

The vaudeville historian Trav S.D., author of No Applause—Just Throw Money, thinks the fact that Don “spoke” German may have been part of his appeal, given the large German immigrant population in New York City at the time. “I wouldn’t be shocked to hear that many German-Americans went out to see their canine countryman utter a few words of their native language out of sheer patriotism and nostalgia,” he told Smithsonian.com.

Don arrived in the U.S. in 1912 at the invitation of the vaudeville impresario and publicity genius William Hammerstein. Hammerstein had hyped Don’s pending visit by putting up a $50,000 bond (more than $1.25 million in today’s dollars) in case the dog died between London and New York; Lloyd’s of London had supposedly refused to insure him. “This makes Don the most valuable dog in the world,” the New York Times reported.

“Don will sail on the Kronprinz Wilhelm next Wednesday,” the Times noted. “A special cabin has been engaged in order to insure his safety.”

When Don’s ship docked, he was greeted like any other visiting celebrity, met by ship reporters hoping for some lively quotes. Unfortunately, as the New York Evening World’s reporter noted, Don was “too seasick on the way over to converse with anybody. As yet, therefore, his opinion of the New York skyline and other local sights is unknown.”

Don would stay in the States for the next two years, appearing first at Hammerstein’s prestigious Roof Garden theater on 42nd Street in New York City, where he performed on the same bill as escape artist Harry Houdini. He then toured the country, performing in Boston, San Francisco, and other cities.

Not every performer of Houdini’s caliber would share the bill with an animal act. Some considered it undignified. Others objected to the way the animals were sometimes treated, especially the often-cruel methods used to train them. Among the latter group were the legendary French actress Sarah Bernhardt, who appeared on the vaudeville stage late in her career, and the hugely popular but now largely forgotten American singer Elsie Janis. Janis once wrote that, “any man who earns his money by the hard, cruel work of dumb beasts should not be known.”

Don seems to have had it relatively easy, though. Wherever he appeared, his act consisted of answering a series of questions served up by his regular straight man and interpreter, a vaudeville veteran known as Loney Haskell. Haskell became so attached to Don, according to the famous New York celebrity columnist O.O. McIntyre, “that in one-night stands he slept in the dog’s kennel.”

Off stage, Don’s purported ability to talk was taken seriously even in academic circles. Lending some credence to the notion that a dog might actually converse, the inventor Alexander Graham Bell had once claimed that as a young man he taught his Skye terrier to say “How are you grandmamma?”

On a 1913 visit to San Francisco, Don and his handlers called on J. C. Merriam, a respected paleontologist at the University of California at Berkeley, who, if contemporary newspaper accounts are to be believed, was “astonished” and “declared his belief that the dog can reason and think for himself.”

Earlier, the respected journal Science had another explanation, based on statements by a University of Berlin professor who had also examined Don. His conclusion, the journal reported in May 1912, was that “the speech of Don is… to be regarded properly as the production of sounds which produce illusions in the hearer.”

In other words, Don’s audience was hearing what it wanted (and had paid) to hear—a genuine talking dog.

The trade paper Variety came to a similar verdict in several enthusiastic, if appropriately skeptical, reviews of the act. “The trained growls which emanate from his throat can readily be mistaken for words,” one reviewer concluded.

Despite his relatively limited vocabulary, Don also became a pioneering celebrity endorser, in his case for Milk-Bone dog biscuits. Referring to Don as “the most valuable money-making dog in the world,” newspaper ads claimed that the cash-cow canine “is fed only on Maltoid Milk-Bone—the Best Food for Your Dogs Too.”

After two years in the U.S., Don seems to have retired and returned to his homeland. Haskell calculated that their stage performances paid Don $92 per word, the equivalent of about $2,300 a word today. That meant his full eight-word performance would have returned the modern equivalent of $18,400—presumably enough to keep him in cakes and/or Milk-Bones for life. (And vaudeville acts typically performed multiple times a day.)

Don reportedly died at home, near Dresden, Germany, in late 1915, when he would have been about 12. His last words, if any, seem to have gone unrecorded.

There would be other “talking” dogs, including Rolf, a German-born terrier who supposedly communicated by a sort of Morse code of his own invention and also solved addition and subtraction problems (circa 1915), and Queen, “positively the only dog in the world that speaks the English language” (circa 1918). Singing dogs had their day, too.

The phenomenon would gradually die out as vaudeville yielded the stage to other forms of entertainment, especially motion pictures. Author Trav S.D., who pays attention to such matters, says he isn’t aware of any “talking” dog acts on the scene today. However, he notes, there are plenty of amateurs to be seen (and heard) on YouTube.

But no dog, however vocally gifted, is likely to capture the American public’s imagination quite like Don. A top dog, if there ever was one.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)