When Emancipation Finally Came, Slave Markets Took on a Redemptive Purpose

During the Civil War, the jails that held the enslaved imprisoned Confederate soldiers. After, they became rallying points for a newly empowered community

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/76/e6764f66-e7a1-4975-86cf-d64350642f99/3a49959r.jpg)

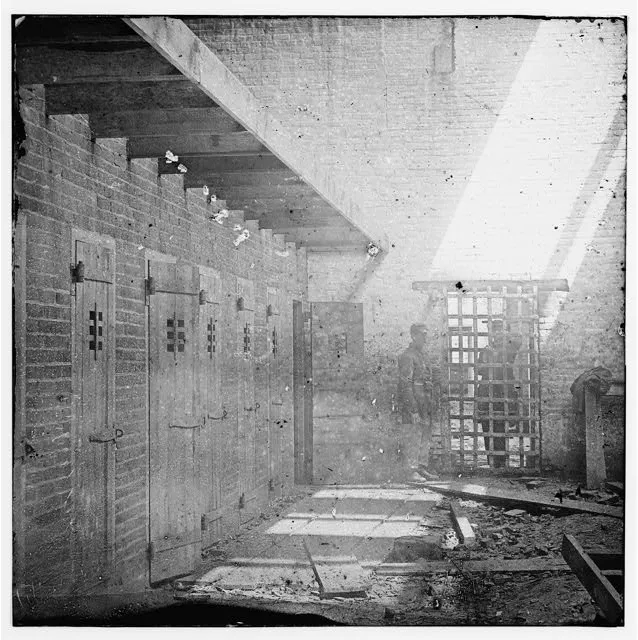

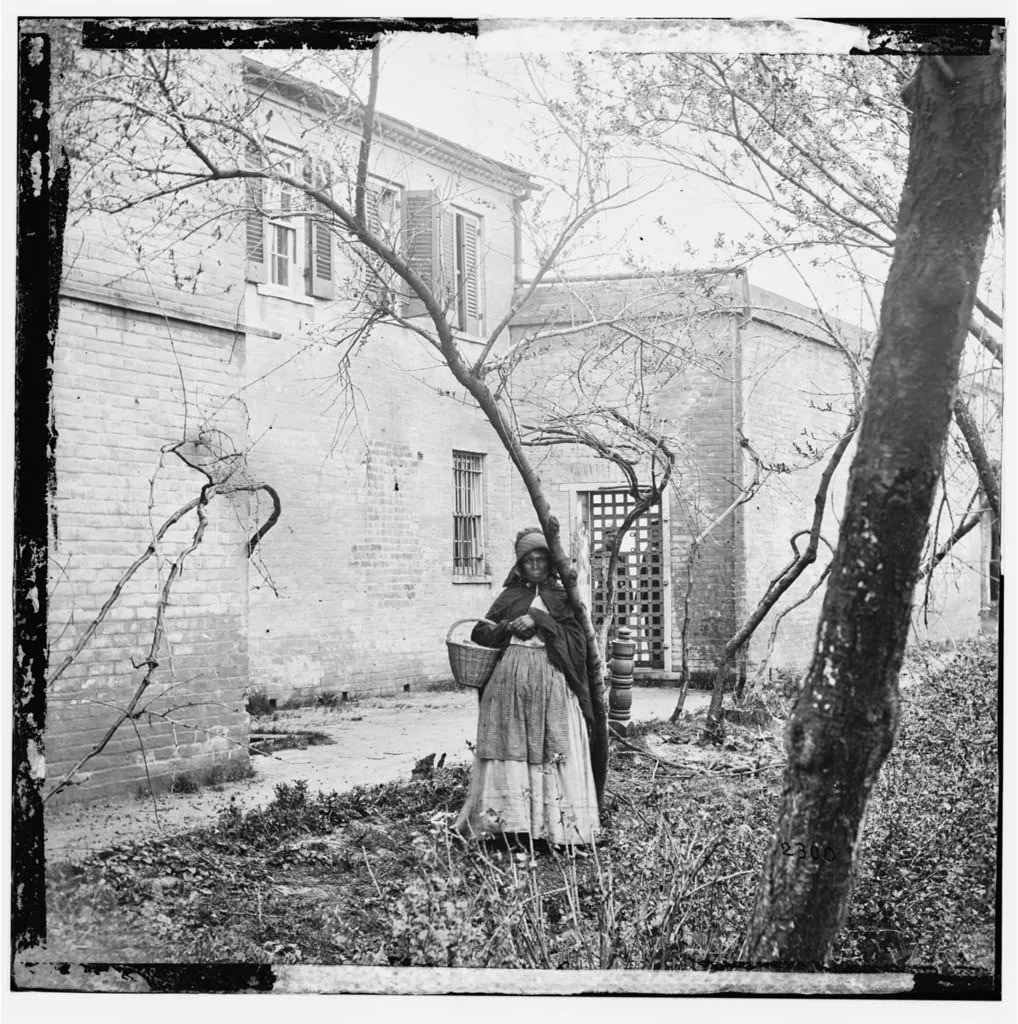

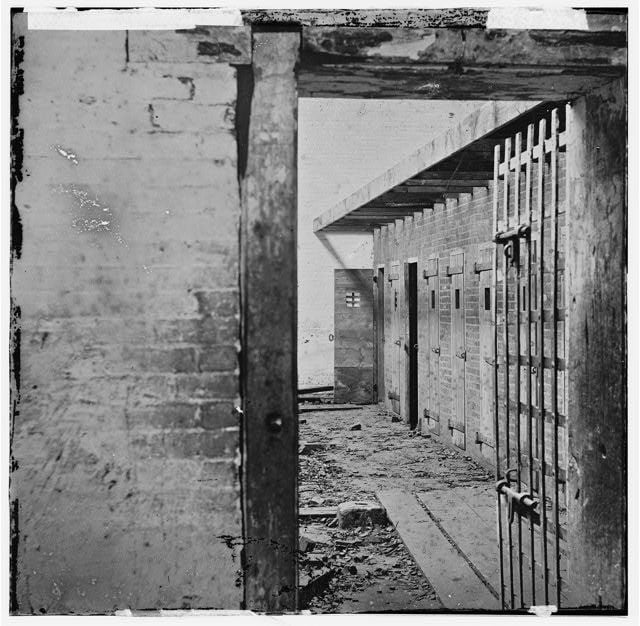

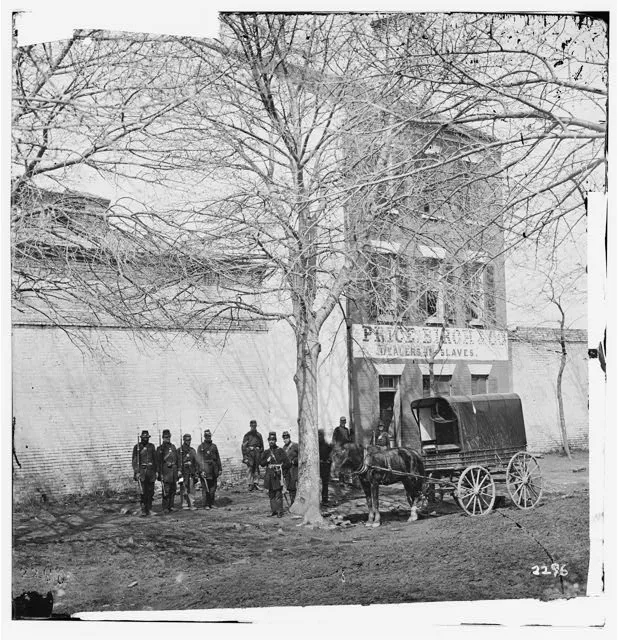

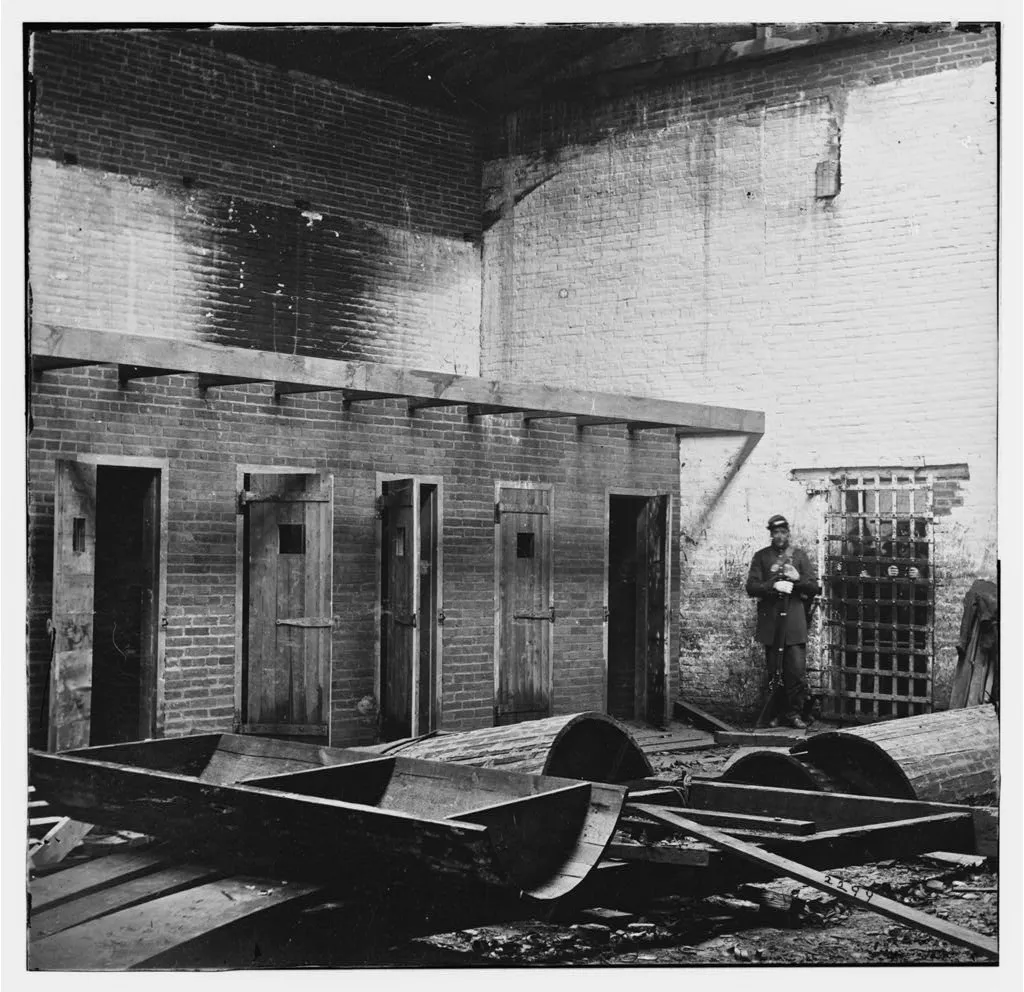

For decades before the Civil War, slave markets, pens and jails served as holding cells for enslaved African-Americans who were awaiting sale. These were sites of brutal treatment and unbearable sorrow, as callous and avaricious slave traders tore apart families, separating husbands from wives, and children from their parents. As the Union army moved south during the Civil War, however, federal soldiers captured and repurposed slave markets and jails for new and often ironic functions. The slave pens in Alexandria, Virginia, and St. Louis, Missouri, became prisons for Confederate soldiers and civilians. When one inmate in St. Louis complained about being held in such “a horrible place,” an unsympathetic Unionist replied matter-of-factly, “Yes, it is a slave-pen.” Other slave markets, such as the infamous “Forks of the Road” at Natchez, Mississippi, became contraband camps—gatherings points for black refugees from bondage, sites of freedom from their masters, and sources of protection and assistance by Union soldiers.

Ex-slaves relished seeing these paradoxical uses of the old slave pens. Jermain Wesley Logan had escaped slavery to New York in 1833 and returned to Nashville in the summer of 1865, where he found his elderly mother and old friends he had not seen for more than 30 years. “The slave-pens, thank God, have changed their inmates,” he wrote. In place of “the poor, innocent and almost heartbroken slaves” who for years had been held captive there as they awaited sale to the Deep South, Loguen found “some of the very fiends in human shape who committed those diabolical outrages.”

Loguen turned his eyes to the heavens. “Their sins have found them out,” he wrote, “and I was constrained to give God the glory, for He has done a great work for our people.”

During and after the war freedmen and women used old slave jails as sites of public worship and education. A black Congregational church met at Lewis Robard’s slave jail in Lexington, Kentucky, while Robert Lumpkin’s notorious brick slave jail in Richmond became the home of a black seminary that is now known as Virginia Union University, a historically black university. “The old slave pen was no longer the ‘devil’s half acre’ but God’s half acre,” wrote one of the seminary’s founders. For slave markets to become centers of black education was an extraordinary development since southern states had prohibited teaching slaves how to read and write.

In December 1864, the local slave market at the corner of St. Julian Street and Market Square in Savannah became a site for black political mobilization and education. A white observer noted the irony of the new use of this place. “I passed up the two flights of stairs down which thousands of slaves had been dragged, chained in coffle, and entered a large hall,” he wrote. “At the farther end was an elevated platform about eight feet square,—the auctioneer’s block. The windows were grated with iron. In an anteroom at the right women had been stripped and exposed to the gaze of brutal men.”

Now, instead of men and women begging unsympathetic buyers and sellers for mercy, a black man was leading a group of the emancipated in prayer, “giving thanks to God for the freedom of his race, and asking for a blessing on their undertaking.” After the prayers, the group broke into song. “How gloriously it sounded now,” wrote the white observer, “sung by five hundred freedmen in the Savannah slave-mart, where some of the singers had been sold in days gone by! It was worth a trip from Boston to Savannah to hear it.”

The next morning, black teachers sat on the auctioneer’s platform in that same room, teaching a school of 100 young black children. “I listened to the recitations, and heard their songs of jubilee,” wrote the witness. “The slave-mart transformed to a school-house! Civilization and Christianity had indeed begun their beneficent work.” Such joy reflected an incredible change. This site “from which had risen voices of despair instead of accents of love, brutal cursing instead of Christian teaching.”

When Union forces entered Charleston, South Carolina, in February 1865, they found the buildings of the business district silent and badly damaged. Prior to the war Charleston had been one of the largest slave markets in the South, and slave traders plied their wares openly and proudly in the city. The slave dealers had set up shop in a slave mart in a “respectable” part of town, near St. Michael’s Church, a seminary library, the courthouse, and other government buildings. The word “MART” was emblazoned in large gilt letters above the heavy iron front gate. Passing through the outer gate, one would enter a hall 60-feet long and 20-feet wide, with tables and benches on either side. At the far end of the hall was a brick wall with a door into the yard. Tall brick buildings surrounded the yard, and a small room to the side of the yard “was the place where women were subjected to the lascivious gaze of brutal men. There were the steps, up which thousands of men, women, and children had walked to their places on the table, to be knocked off to the highest bidder.”

Walking along the streets, northern journalist Charles C. Coffin saw the old guardhouse where “thousands of slaves had been incarcerated there for no crime whatever, except for being out after nine o’clock, or for meeting in some secret chamber to tell God their wrongs, with no white man present.” Now the guardhouse doors “were wide open,” no longer patrolled by a jailor. “The last slave had been immured within its walls, and St. Michael’s curfew was to be sweetest music thenceforth and forever. It shall ring the glad chimes of freedom,—freedom to come, to go, or to tarry by the way; freedom from sad partings of wife and husband, father and son, mother and child.”

While Coffin stood gazing at these sites, imaging innumerable scenes of hopelessness and horror, a black woman named Dinah More walked into the hall and addressed him. “I was sold there upon that table two years ago,” she told him. “You never will be sold again,” Coffin replied; “you are free now and forever!” “Thank God!” replied More. “O the blessed Jesus, he has heard my prayer. I am so glad; only I wish I could see my husband. He was sold at the same time into the country, and has gone I don’t know where.”

Coffin went back to the front of the building and took down a gilt star from the front of the mart and, with the assistance of a freedman, he also removed the letters “M-A-R-T” and the lock from the iron gate. “The key of the French Bastile hangs at Mount Vernon,” wrote Coffin, “and as relics of the American prison-house then being broken up, I secured these.”

Coffin next went to the offices of the slave brokers. The cellar dungeons were complete with bolts, chains and manacles for securing captives to the floors. Books, papers, letters and bills of sale were strewn upon the floor. He picked up some papers and read them. Their callous disregard of human life and feeling was appalling. One stated, “I know of five very likely young negroes for sale. They are held at high prices, but I know the owner is compelled to sell next week, and they may be bought low enough so as to pay. Four of the negroes are young men, about twenty years old, and the other a very likely young woman about twenty-two. I have never stripped them, but they seem to be all right.”

Another offered to “buy some of your fancy girls and other negroes, if I can get them at a discount.” A third spoke of a 22-year-old black woman: “She leaves two children, and her owner will not let her have them. She will run away. I pay for her in notes, $650. She is a house woman, handy with the needle, in fact she does nothing but sew and knit, and attend to house business.”

Taking in these horrors, Coffin thought that perhaps some of the Massachusetts abolitionists, like Governor John A. Andrew, Wendell Phillips, or William Lloyd Garrison, might like to speak from the steps of the slave mart. Within a month, such a scene would take place. Coffin sent the steps northward to Massachusetts, and on March 9, 1865, Garrison gave a rousing speech while standing on them at Music Hall in Boston. Garrison and Coffin stood on the stage, which also featured the large gilt letters, “MART” and the lock from the iron door where black women had been examined for sale. The audience raised “thunders of applause” and waved “hundreds of white handkerchiefs for a considerable interval.”

And Garrison took great pride in the proceedings. “I wish you could have seen me mounted on the Charleston slave auction-block, on Thursday evening of last week, in Music Hall, in the presence of a magnificent audience, carried away with enthusiasm, and giving me their long protracted cheers and plaudits!” Garrison wrote to a friend. A few days later the “slave steps” went to Lowell, Massachusetts, where Garrison, Coffin and others delivered speeches celebrating the end of slavery and the Civil War. The audience applauded wildly as they listened to the speakers at the steps.

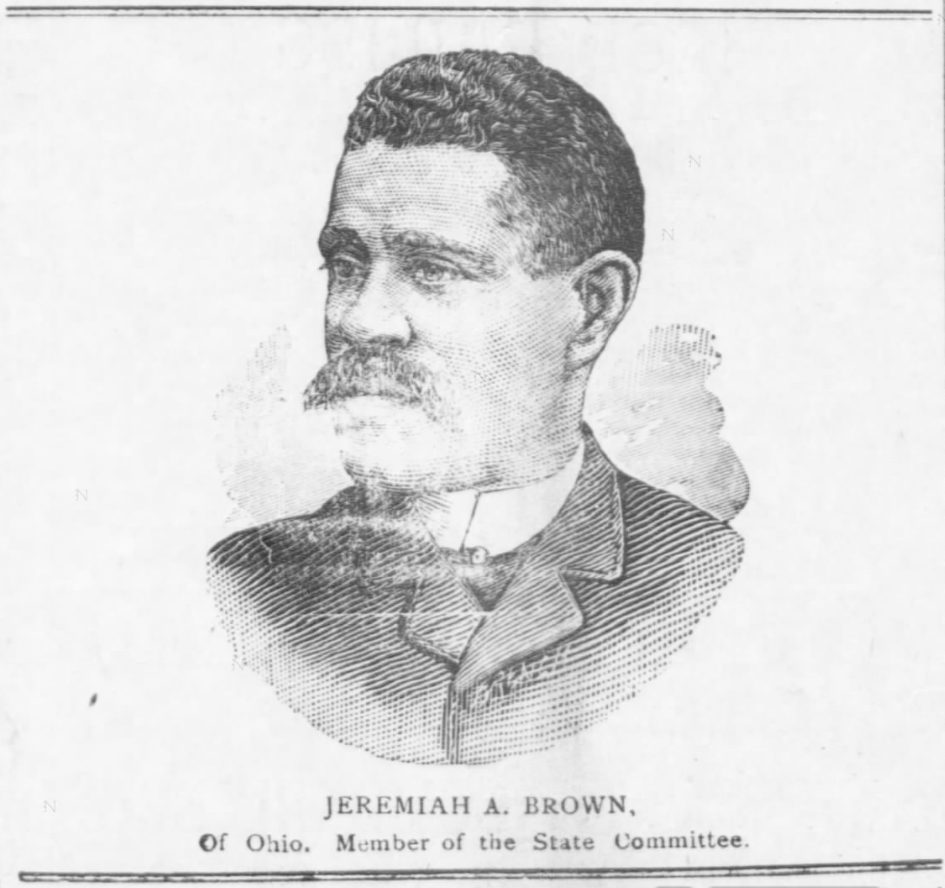

In the postwar era, slave markets and jails served as signposts of how far the nation had come since the Civil War. In 1888 a group of Ohio state legislators traveled to New Orleans, where they saw the Planters’ House, which still featured the words “Slaves for sale” painted on the outside wall. Now, however, the house served as “the headquarters for colored men in New Orleans.” Seeing these men “now occupying this former slave market, as men and not as chattels, is one of the pleasing sights that cheer us after an absence of thirty-two years from the city,” wrote Jeremiah A. Brown, a black state legislator traveling with the group. Upon visiting the old slave market in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1916, another African-American man similarly reflected on the meaning of this old “relic of slavery” and “the wonderful progress made.” He concluded, “The Lord hath done great things for us, whereof we are glad.”

The open-air market at St. Augustine still stands today in the middle of the city’s historic quarter. In the twentieth century it became a focal point for anti-discrimination protests in the city. In 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr., led nonviolent civil rights marches around the building, but violence broke out there between civil rights marchers and white segregationists on other occasions. In 2011, the city erected monuments to the “foot soldiers”—both white and black—who had marched in St. Augustine for racial equality in the 1960s. The juxtaposition of the market with the monuments to the Civil Rights Movement tells a story powerful of change over time in American history.

Several former slave markets now house museums about African-American history. The old slave mart in Charleston, South Carolina, has been interpreting the history of slavery in that city since 1938. More recently, the Northern Virginia chapter of the Urban League established the Freedom House museum at its headquarters in Alexandria—the old slave pen that had become a prison for Confederates during the Civil War. Further west, the slave pen from Mason County, Kentucky, is now on display at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati. Historical markers also commemorate the sites of slave markets throughout the nation, reminding the public that human beings were not only bought and sold in the South. In 2015, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio unveiled a marker about the slave trade in Lower Manhattan. And those slave steps from Charleston? According to the South Carolina museum, they are believed to be in a collection in Boston, but their true location is unclear.

The transformation and commemoration of old slave markets into educational institutions and sites of political mobilization serve as powerful reminders of the massive social change that swept through the United States during the Civil War. Four million enslaved human beings became free between 1861 and 1865, forever escaping the threat of future sale. And nearly 200,000 black men donned the blue uniform of the Union so that they, too, could join in the fight for freedom. The old abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison sensed this transformation when he delivered his address at Music Hall in Boston, while standing on the steps of the Charleston slave mart. “What a revolution!” he exulted.