When the Idea of Home Was Key to American Identity

From log cabins to Gilded Age mansions, how you lived determined where you belonged

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/07/b40762a3-ea18-440a-9410-6564ac3e7dc4/white-wimtba-on-home-image-16.jpg)

Like viewers using an old-fashioned stereoscope, historians look at the past from two slightly different angles—then and now. The past is its own country, different from today. But we can only see that past world from our own present. And, as in a stereoscope, the two views merge.

I have been living in America’s second Gilded Age—our current era that began in the 1980s and took off in the 1990s—while writing about the first, which began in the 1870s and continued into the early 20th century. The two periods sometimes seem like doppelgängers: worsening inequality, deep cultural divisions, heavy immigration, fractious politics, attempts to restrict suffrage and civil liberties, rapid technological change, and the reaping of private profit from public governance.

In each, people debate what it means to be an American. In the first Gilded Age, the debate centered on a concept so encompassing that its very ubiquity can cause us to miss what is hiding in plain sight. That concept was the home, the core social concept of the age. If we grasp what 19th-century Americans meant by home, then we can understand what they meant by manhood, womanhood, and citizenship.

I am not sure if we have, for better or worse, a similar center to our debates today. Our meanings of central terms will not, and should not, replicate those of the 19th century. But if our meanings do not center on an equivalent of the home, then they will be unanchored in a common social reality. Instead of coherent arguments, we will have a cacophony.

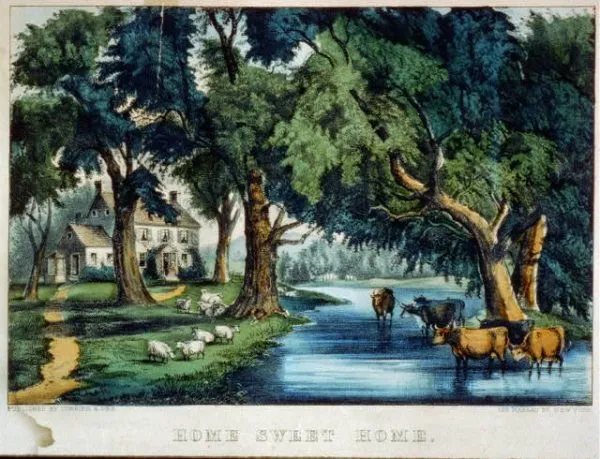

When reduced to the “Home Sweet Home” of Currier and Ives lithographs, the idea of “home” can seem sentimental. Handle it, and you discover its edges. Those who grasped “home” as a weapon caused blood, quite literally, to flow. And if you take the ubiquity of “home” seriously, much of what we presume about 19th-century America moves from the center to the margins. Some core “truths” of what American has traditionally meant become less certain.

It’s a cliché, for example, that 19th-century Americans were individualists who believed in inalienable rights. Individualism is not a fiction, but Horatio Alger and Andrew Carnegie no more encapsulated the dominant social view of the first Gilded Age than Ayn Rand does our second one. In fact, the basic unit of the republic was not the individual but the home, not so much isolated rights-bearing-citizen as collectives—families, churches, communities, and volunteer organizations. These collectives forged American identities in the late-19th century, and all of them orbited the home. The United States was a collection of homes.

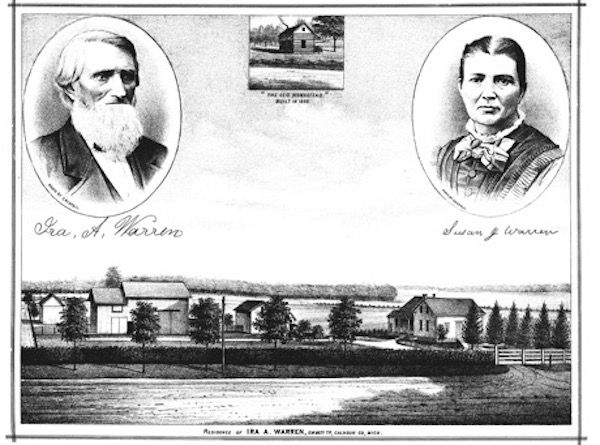

Evidence of the power of the home lurks in places rarely visited anymore. Mugbooks, the illustrated county histories sold door to door by subscription agents, constituted one of the most popular literary genres of the late-19th century. The books became monuments to the home. If you subscribed for a volume, you would be included in it. Subscribers summarized the trajectories of their lives, illustrated on the page. The stories of these American lives told of progress from small beginnings—symbolized by a log cabin—to a prosperous home.

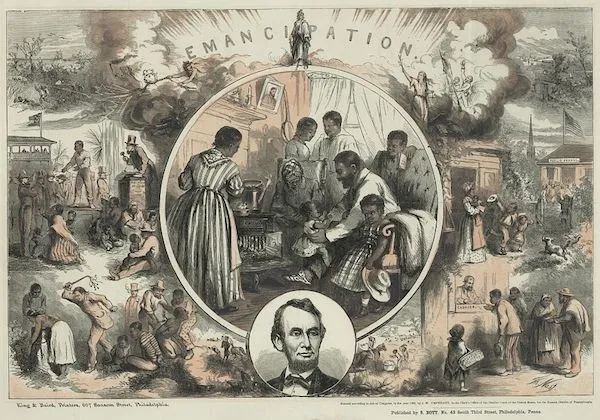

The concept of the home complicated American ideas of citizenship. Legally and constitutionally, Reconstruction proclaimed a homogenous American citizenry, with every white and black man endowed with identical rights guaranteed by the federal government.

In practice, the Gilded Age mediated those rights through the home. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments established black freedom, citizenship, civil rights, and suffrage, but they did not automatically produce homes for black citizens. And as Thomas Nast recognized in one of his most famous cartoons, the home was the culmination and proof of freedom.

Thus the bloodiest battles of Reconstruction were waged over the home. The Klan attacked the black home. Through murder, arson, and rape, Southern terrorists aimed to impart a lesson: Black men could not protect their homes. They were not men and not worthy of the full rights of citizenship.

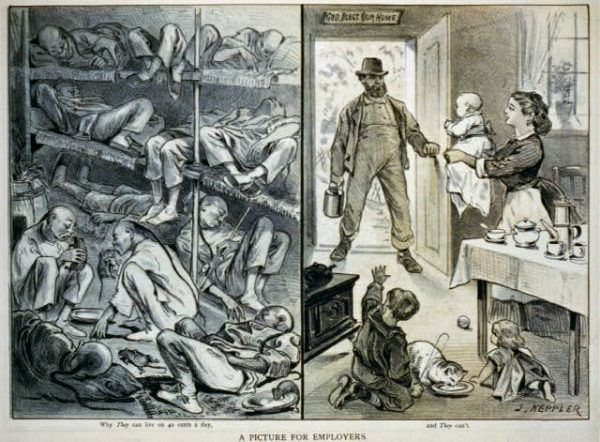

In attacking freedpeople, terrorists sought to make them cultural equivalents of Chinese immigrants and Indians—those who, purportedly, failed to establish homes, could not sustain homes, or attacked white homes. Their lack of true homes underlined their supposed unsuitability for full rights of citizenship. Sinophobes repeated this caricature endlessly.

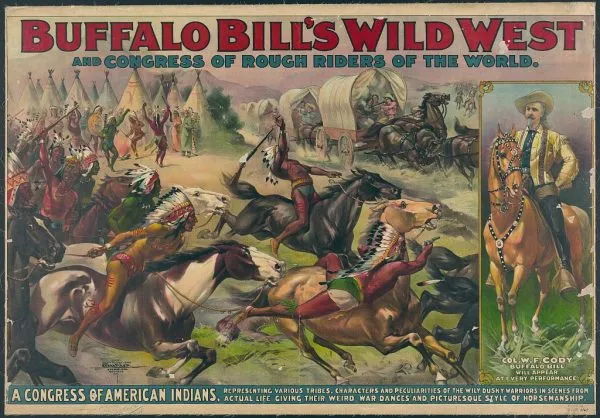

In the iconography of the period, both so-called “friends” of the Indian and Indian haters portrayed Indians as lacking true homes and preventing whites from establishing homes. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had Indians attacking cabins and wagon trains full of families seeking to establish homes. They were male and violent, but they were not men. Americans decided who were true men and women by who had a home. Metaphorically, Indians became savages and animals.

Even among whites, a category itself constantly changing during this and other eras, the home determined which people were respectable or fully American. You could get away with a lot in the Gilded Age, but you could neither desert the home nor threaten it. Horatio Alger was a pedophile, but this is not what ultimately cost him his popularity. His great fault, as women reformers emphasized, was that his heroes lived outside the home.

Position people outside the home and rights as well as respectability slip away. Tramps were the epitome of the era’s dangerous classes. Vagrancy—homelessness—became a crime. Single working women were called “women adrift” because they had broken free of the home and, like Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, threatened families. (Carrie broke up homes but she, rather than the men who thought they could exploit her, survived.) European immigrants, too, found their political rights under attack when they supposedly could not sustain true homes. Tenements were, in the words of Jacob Riis, “the death of the home.”

As the great democratic advances of Reconstruction came under attack, many of the attempts to restrict suffrage centered on the home. Small “l” liberal reformers—people who embraced market freedom, small government, and individualism but grew wary of political freedom—sought to reinstitute property requirements. Failing that, they policed voting, demanding addresses for voter registration, a seemingly simple requirement, but one that required permanent residences and punished the transience that accompanied poverty. Home became the filter that justified the exclusion of Chinese immigrants, Indian peoples, eventually African-Americans, transients, and large numbers of the working poor.

The home always remained a two-edged sword. American belief in the republic as a collection of homes could and did become an instrument for exclusion, but it could also be a vehicle for inclusion. Gilded-Age social reformers embraced the home. The Homestead Act sought to expand the creation of homes by both citizens and non-citizens. When labor reformers demanded a living wage, they defined it in terms of the money needed to support a home and family. Freedpeople’s demands for 40 acres and a mule were demands for a home. Frances Willard and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union made “home protection” the basis of their push for political power and the vote for women. Cities and states pushed restrictions on the rights of private landholders to seek wealth at the expense of homes. In these cases, the home could be a weapon for enfranchisement and redistribution. But whether it was used to include or exclude, the idea of home remained at the center of Gilded-Age politics. To lose the cultural battle for the home was to lose, in some cases, virtually everything.

The idea of home has not vanished. Today a housing crisis places homes beyond the reach of many, and the homeless have been exiled to a place beyond the polity. But still, the cultural power of the home has waned.

A new equivalent of home—complete with its transformative powers for good and ill—might be hiding in plain sight, or it could be coming into being. When I ask students, teachers, and public audiences about a modern equivalent to the Gilded-Age home, some suggest family, a concept increasingly deployed in different ways by different people. But I have found no consensus.

If we cannot locate a central collective concept which, for better or worse, organizes our sense of being American, then this second Gilded Age has become a unique period in American history. We will have finally evolved into the atomized individuals that 19th-century liberals and modern libertarians always imagined us to be.

The alternative is not a single set of values, a kind of catechism for Americans, but rather a site where we define ourselves around our relationships to each other rather than by our autonomy. We would quarrel less over what we want for ourselves individually than over what we want collectively. Articulating a central concept that is the equivalent of the 19th-century idea of home would not end our discussions and controversies, but it would center them on something larger than ourselves.

I wish I could announce the modern equivalent of home, but I am not perceptive enough to recognize it yet. I do know that, once identified, the concept will become the ground that anyone seeking to define what it is to be an American must seize.

Richard White, the Margaret Byrne Professor of American History at Stanford University, is the author of The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896. He wrote this essay for What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.