When New York City Tamed the Feared Gunslinger Bat Masterson

The lawman had a reputation to protect—but that reputation shifted after he moved East

![]()

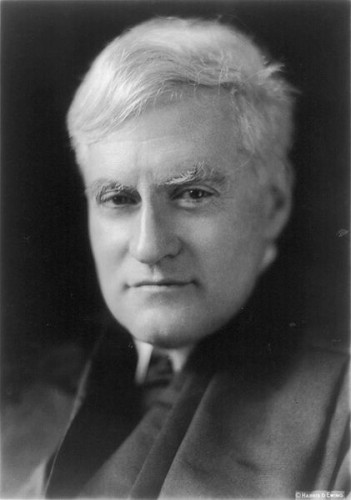

Bat Masterson spent the last half of his life in New York, hobnobbing with Gilded Age celebrities and working a desk job that saw him churning out sports reports and “Timely Topics” columns for the New York Morning Telegraph. His lifestyle had widened his waistline, belying the reputation he had earned in the first half of his life as one of the most feared gunfighters in the West. But that reputation was built largely on lore; Masterson knew just how to keep the myths alive, as well as how to evade or deny his past, depending on whichever stories served him best at the time.

Despite his dapper appearance and suave charm, Masterson could handle a gun. And despite his efforts to deny his deadly past, late in his life he admitted, under cross-examination in a lawsuit, that he had indeed killed. It took a future U.S. Supreme Court justice, Benjamin Cardozo, to get the truth out of Masterson. Some of it, anyway.

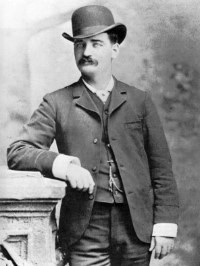

William Barclay “Bat” Masterson was born in Canada in 1853, but his family—he had five brothers and two sisters—ultimately settled on a farm in Sedgwick County, Kansas. At age 17, Masterson left home with his brothers Jim and Ed and went west, where they found work on a ranch near Wichita. “I herded buffalo out there for a good many years,” he later told a reporter. “Killed ‘em and sold their hides for $2.50 apiece. Made my living that way.”

Masterson’s prowess with a rifle and his knowledge of the terrain caught the attention of General Nelson Appleton Miles, who, after his highly decorated service with the Union Army in the Civil War, had led many a campaign against American Indian tribes across the West. From 1871-74, Masterson signed on as a civilian scout for Miles. “That was when the Indians got obstreperous, you remember,” he told a reporter.

Masterson was believed to have killed his first civilian in 1876, while he was working as a faro dealer at Henry Fleming’s Saloon in Sweetwater, Texas. Fleming also owned a dance hall, and it was there that Masterson tangled with an Army Sergeant who went by the name of Melvin A. King over the affections of a dance-hall girl named Mollie Brennan.

Masterson had been entertaining Brennan after hours and alone in the club when King came looking for Brennan. Drunk and enraged at finding Masterson with her, King pulled a pistol, pointed it at Masterson’s groin, and fired. The shot knocked the young faro dealer to the ground. King’s second shot pierced Brennan’s abdomen. Wounded and bleeding badly, Masterson drew his pistol and returned fire, hitting King in the heart. Both King and Brennan died; Masterson recovered from his wounds, though he did use a cane sporadically for the rest of his life. The incident became known as the Sweetwater Shootout, and it cemented Bat Masterson’s reputation as a hard man.

News of a gold strike in the Black Hills of South Dakota sent Masterson packing for the north. In Cheyenne, he went on a five-week winning streak on the gambling tables, but he tired of the town and had left when he ran into Wyatt Earp, who encouraged him to go to Dodge City, Kansas, where Bat’s brothers Jim and Ed were working in law enforcement. Masterson, Earp told him, would make a good sheriff of Ford County someday, and ought to run for election.

Masterson ended up working as a deputy alongside Earp, and within a few months, he won election to the sheriff’s job by three votes. Right away, Masterson was tasked with cleaning up Dodge, which by 1878 had become a hotbed of lawless activity. Murders, train robberies and Cheyenne Indians who had escaped from their reservation were just a few of the problems Masterson and his marshals confronted early in his term. But on the evening of April 9, 1878, Bat Masterson drew his pistol to avenge the life of his brother. This killing was kept apart from the Masterson lore.

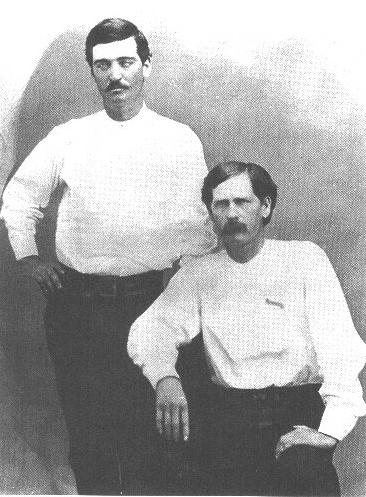

City Marshal Ed Masterson was at the Lady Gay Saloon, where trail boss Alf Walker and a handful of his riders were whooping it up. One of Walker’s men, Jack Wagner, displayed his six-shooter in plain sight. Ed approached Wagner and told him he’d have to check his gun. Wagner tried to turn it over to the young marshal, but Ed told Wagner he’d have to check it with the bartender. Then he left the saloon.

A few moments later, Walker and Wagner staggered out of the Lady Gay. Wagner had his gun, and Ed tried to take it from him. A scuffle ensued, as onlookers spilled out onto the street. A man named Nat Haywood stepped in to help Ed Masterson, but Alf Walker drew his pistol, pushed it into Haywood’s face and squeezed the trigger. His weapon misfired, but then Wagner drew his gun and shoved it into Masterson’s abdomen. A shot rang out and the marshal stumbled backward, his coat catching fire from the muzzle blast.

Across the street, Ford County Sheriff Bat Masterson reached for his gun as he chased Wagner and Walker. From 60 feet away, Masterson emptied his gun, hitting Wagner in the abdomen and Walker in the chest and arm.

Bat then tended to his brother, who died in his arms about a half hour after the fight. Wagner died not long afterward, and Walker, alive but uncharged, was allowed to return to Texas, where Wyatt Earp reported that he later died from pneumonia relating to his wounded lung.

Newspapers at the time attributed the killing of Jack Wagner to Ed Masterson; they said he had returned fire during the melee. It was widely believed that this account was designed to keep Bat Masterson’s name out of the story to prevent any “Texas vengeance.” Despite the newspaper accounts, witnesses in Dodge City had long whispered the tale of the Ford County sheriff calmly shooting down his brother’s assailants on the dusty street outside the Lady Gay.

Masterson spent the next 20 years in the West, mostly in Denver, where he gambled, dealt faro in clubs and promoted prize fights. In 1893 he married Emma Moulton, a singer and juggler who remained with Masterson for the rest of his life.

The couple moved to New York in 1902, where Masterson picked up work as a newspaperman, writing mostly about prizefighting at first, but then also covering politics and entertainment in his New York Morning Telegraph column, “Masterson’s Views on Timely Topics.” A profile of him written about him 20 years before in the New York Sun followed Masterson to the East Coast, cementing the idea that he had killed 28 men out west. Masterson never did much to dispute the stories or the body count, realizing that his reputation did not suffer. His own magazine essays on life on the Western frontier led many to believe he was exaggerating tales of bravery for his own benefit. But in 1905, he played down the violence of his past, telling a reporter for the New York Times, “I never killed a white person that I remember—might have aimed my gun at one or two.”

He had good reason to burnish his reputation. That year, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Masterson deputy U.S. marshal for the Southern District of New York—an appointment he held until 1912. Masterson began traveling in higher social circles, and became more protective of his name. So he was not pleased to find that a 1911 story in the New York Globe and Commercial Advertiser quoted a fight manager named Frank B. Ufer as saying Masterson had “made his reputation by shooting drunken Mexicans and Indians in the back.”

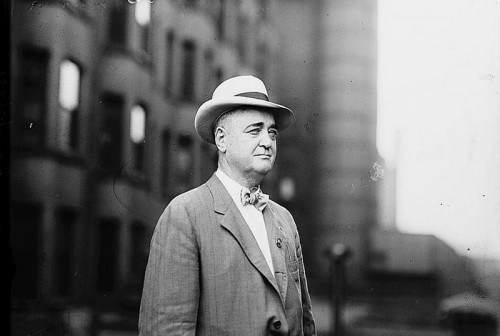

Masterson retained a lawyer and filed a libel suit, Masterson v. Commercial Advertiser Association. To defend itself, the newspaper hired a formidable New York attorney, Benjamin N. Cardozo. In May 1913, Masterson testified that Ufer’s remark had damaged his reputation and that the newspaper had done him “malicious and willful injury.” He wanted $25,000 in damages.

Future Supreme Court justice Benjamin Cardozo cross-examined Bat Masterson in a libel trial in 1913. Photo: Wikipedia

In defense of the newspaper, Cardozo argued that Masterson was not meant to be taken seriously—as both Masterson and Ufer were “sporting men” and Ufer’s comments were understood to be “humorous and jocular.” Besides, Cardozo argued, Masterson was a known “carrier of fire arms” and had indeed “shot a number of men.”

When questioned by his attorney, Masterson denied killing any Mexicans; any Indians he may have shot, he shot in battle (and he could not say whether any had fallen). Finally, Cardozo rose to cross-examine the witness. “How many men have you shot and killed in your life?” he asked.

Masterson dismissed the reports that he had killed 28 men, and to Cardozo, under oath, he guessed that the total was three. He admitted to killing King after King had shot him first in Sweetwater. He admitted to shooting a man in Dodge City in 1881, but he wasn’t certain whether the man died. And then he confessed that he, and not his brother Ed, had shot and killed Wagner. Under oath, Bat Masterson apparently felt compelled to set the record straight.

“Well, you are proud of those exploits in which you killed men, aren’t you?” Cardozo asked.

“Oh, I don’t think about being proud of it,” Masterson answered. “I do not feel that I ought to be ashamed about it; I feel perfectly justified. The mere fact that I was charged with killing a man standing by itself I have never considered an attack upon my reputation.”

The jury granted Masterson’s claim, awarding him $3,500 plus $129 in court costs. But Cardozo successfully appealed the verdict, and Masterson eventually accepted a $1,000 settlement. His legend, however, lived on.

Sources

Books: Robert K. DeArment, Bat Masterson: The Man and the Legend, University of Oklahoma Press, 1979. Robert K. DeArment, Gunfighter in Gotham: Bat Masterson’s New York City Years, University of Oklahoma Press, 2013. Michael Bellesiles, Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture, Soft Skull Press, 2000.

Articles: “They Called Him Bat,” by Dale L. Walker, American Cowboy, May/June 2006. “Benjamin Cardozo Meets Gunslinger Bat Masterson,” by William H. Manz, New York State Bar Association’s Journal, July/August 2004. “‘Bat’ Masterson Vindicated: Woman Interviewer Gives Him ‘Square Deal,’ ” by Zoe Anderson Norris, New York Times April 2, 1905. “W.B. ‘Bat’ Masterson, Dodge City Lawman, Ford County Sheriff,” by George Laughead, Jr. 2006, Ford County Historical Society, http://www.skyways.org/orgs/fordco/batmasterson.html. ”Bat Masterson and the Sweetwater Shootout,” by Gary L. Roberts, Wild West, October, 2000, http://www.historynet.com/bat-masterson-and-the-sweetwater-shootout.htm. “Bat Masterson: Lawman of Dodge City,” Legends of Kansas, http://www.legendsofkansas.com/batmasterson.html. “Bat Masterson: King of the Gunplayers,” by Alfred Henry Louis, Legends of America, http://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-batmasterson.html.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)