When a Quake Shook Alaska, a Radio Reporter Led the Public Through the Devastating Crisis

In the hours after disaster struck Anchorage, an unexpected figure named Genie Chance came to the rescue

:focal(2485x894:2486x895)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/27/6b27e4f8-73a7-4e08-8a23-d4bf0b3ebb86/genie_with_mic.jpg)

“This is Genie Chance, reporting from inside the Public Safety Building,” she began from her new post at the Anchorage, Alaska, police station. The scuttle and din of everyone working around her bled into her microphone as she spoke.

It was about 8:30 pm, on Good Friday, March 27, 1964. Three hours earlier, just before sundown, the most powerful earthquake ever measured in North America struck Alaska; the epicenter was 75 miles east of Anchorage. In those days, the state of Alaska was still brand-new and often disregarded as a kind of free-floating addendum to the rest of America. But Anchorage was Alaska’s biggest and proudest city, a modern-day frontier town that imagined it was a metropolis, straining to make itself real.

Genie Chance was a working mother and part time radio reporter at local radio station KENI who’d hustled to the police station within minutes of the quake to gather information to report. Now, with everyone scrambling, Anchorage’s police chief had effectively made her the city’s public information officer: It would be up to her to decide whether to put the information and requests people passed to her over the air.

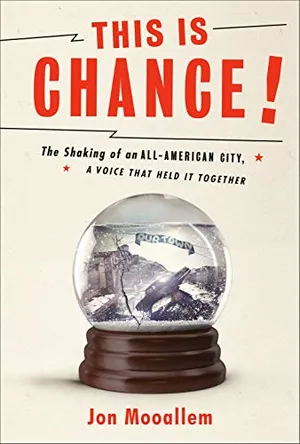

This Is Chance!: The Shaking of an All-American City, A Voice That Held It Together

Drawing on thousands of pages of unpublished documents, interviews with survivors, and original broadcast recordings, This Is Chance! is the hopeful, gorgeously told story of a single catastrophic weekend and proof of our collective strength in a turbulent world.

Anchorage’s city manager swept through, ordering Genie to put out a call for diesel fuel. A public health official stood over her shoulder while she repeated his instructions for purifying snow for drinking water. A police lieutenant requested that an electrician hurry to Presbyterian Hospital. While Genie made one announcement, others zipped onto the counter in front of her. “Providence Hospital needs six cases of six-inch plaster of Paris,” she said. “All electricians and plumbers at Fort Richardson, please go to Building 700 immediately.”

It was stressful; the responsibility was daunting. The highways out of Anchorage appeared to be impassable. The airport and railways were closed. Genie understood that everyone would be trapped together inside this crippled city for the foreseeable future—in the snow, in the dark, with no electricity, in below-freezing temperatures. Under those circumstances, she felt, “mass hysteria would have meant total destruction.” She continued to worry about the possibility, even the inevitability, of such a breakdown of civil society, and felt it was her responsibility to stave off that mayhem.

She found herself scrutinizing each new bit of information that reached her: Was it knowledge the public could handle, or would it generate panic? And how much could she withhold before listeners turned suspicious and stopped trusting her? It also seemed possible that the accuracy of any given piece of information could have slipped, as messages made their way from the far corners of Anchorage into the building like so many games of telephone. Lots of people bringing Genie messages were volunteers, after all— ordinary citizens, many of whom seemed no more qualified to handle such a crisis than Genie was—and everyone was working so quickly that much of the knowledge circulating was imperfect or incomplete.

Earlier, for example, the city attorney informed Genie that the municipal court building could be opened up as a shelter for those who’d evacuated their homes, but also asked her who was in charge of inspecting the structure to ensure it was safe. Genie had no idea. It was unsettling, in retrospect, that Anchorage’s city attorney was asking her.

She wondered how she had wound up in this role. Shouldn’t authority figures, like the police chief and the city manager, be talking over the radio themselves? She suspected the public might trust those men’s voices more than hers. The previous June, Genie had covered the crash of a Northwest Orient Airlines flight chartered by the military to transport nearly a hundred soldiers and their family members from Washington State to Anchorage. The plane had gone down in the ocean, killing everyone aboard. Genie had reported on the search effort tirelessly for three days. But when a correspondent for NBC’s national newscast called her station from New York, looking to air its coverage of the crash, he asked the station to send a male reporter to redo all of Genie’s interviews. It felt too unorthodox, or unserious, for a woman’s voice to inform the American people of a tragedy. Only after the correspondent took it up with his bosses did he agree to put Genie on the air.

Yet here she was in the middle of a disaster—without any instructions or guidelines. People kept coming into the building and hurrying straight to Genie’s counter, entrusting her with the starkest damage reports and updates. “I don’t know why,” she later explained; merely standing behind a microphone seemed to give her a sufficient air of authority. As the night wore on and information kept raining in sideways, everyone seemed to move around the building so quickly, “with this brilliant, tense look in their eyes,” Genie said—“everybody doing a job.” Then, around 9:30 p.m., a sturdy-looking, middle-aged man in the uniform of a high-ranking military officer walked calmly out of that feverish blur of bodies and beamed a small, confident smile in Genie’s direction. He sat down beside her and watched patiently as she stood talking, waiting his turn.

The man seemed to occupy a different atmosphere than everyone else in the lobby, to have coasted toward her in a small depressurized pocket of his own. Genie knew many of the commanding officers at the two military bases outside Anchorage, yet this officer at the Public Safety Building was unfamiliar to Genie. Finally, when she could spare a second, she turned and asked him, “Who are you?”

“I’m Carroll,” he said.

Major General Thomas P. Carroll was adjutant general of Alaska’s National Guard. He happened to be overseeing a training encampment north of Anchorage that week and had immediately ordered his soldiers onto trucks and led them into town. “I have 150 men here,” he told Genie. They were waiting outside, ready to pitch in.

The military had been working with the city since earlier that evening, deploying drivers and vehicles and tanks of potable water— whatever resources it could. Still, something about Carroll’s appearance at the Public Safety Building felt viscerally reassuring for Genie, and seemed to generate the first surge of genuine relief she’d experienced since learning that her two younger children unharmed at home. Carroll just projected competence. (The man had once single- handedly gunned down 18 ambushing Nazis at once; he was prepared to tackle this mess, too.)

Carroll told Genie he needed her help as well. He was looking for a way to reach Juneau, the state capital. Lines of communication were still scarce, and Carroll wanted official permission from the governor to keep his guardsmen on duty. Genie told him to go out to the parking lot and find a ham radio operator named Walt Sauerbier.

Among the many citizens of Anchorage who’d leapt into action that evening was a small legion of amateur ham radio operators. Anchorage was said to have more hams per capita than any other state at the time; it was an amusing hobby to get people through the winter, and an easy way for Alaskans to stay in touch with family. A number of hams in the city had previously organized themselves into a preparedness group and practiced emergency communications during nuclear war simulations. After the quake, many flocked to the parking lot of the Public Safety Building or took up posts at other critical locations around Anchorage, hunkering in their radio-equipped cars to function as a kind of substitute telephone service.

The man Genie had hooked up with, Walt Sauerbier, had been among the first to show up. He was a 61-year-old mechanic who’d been driving around, idly chatting on his mobile unit with someone in Hawaii, when the quake struck. He would work at the Public Safety Building, sending and receiving messages, for 16 straight hours.

Carroll went outside to find Sauerbier and returned to Genie’s police counter a few minutes later. He told Genie he’d reached the governor’s office, and everything was squared away: Carroll’s National Guardsmen were now officially at Anchorage’s disposal. Genie reported this news over KENI, then pulled Carroll in for an interview on the air.

“You got here so quickly!” she began. “You got your group right in the spirit and you arrived at the Public Safety Building in such short order.”

Well, Carroll explained, it was lucky that the earthquake struck during the Guard’s annual two- week training at Camp Denali. “This is the one time of year when all of the guardsmen, from approximately 75 villages and cities in Alaska, are here in Anchorage,” he said. Many of Carroll’s men were Alaska Natives from remote villages around the state: so-called Eskimo Scouts, drawn from the Aleut, Athabascan, Inupiat, Tlingit, and other ethnic groups that had been disproportionately represented in Alaska’s National Guard since World War II, when the military armed and organized Native men to protect the territory’s coastlines from a potential Japanese invasion. “This was our last day of camp,” Carroll said. “We were all starting for home at midnight tonight— though those plans have been canceled.”

Carroll appeared impervious to the ruthless disorder that had swallowed Anchorage. Four weeks later, however, that randomness would rear up again and claim him: Carroll would plummet into Prince William Sound aboard a C-123 twin-engine cargo plane after taking off from the town of Valdez. He had just dropped off the governor to examine the earthquake and tsunami damage there. All four people on board were killed.

***

The military was projecting that a tsunami might shoot up Cook Inlet and strike the city of Anchorage. Tidal waves had already thrashed the towns of Valdez, Seward and Kodiak, and the villages of Kaguyak, Old Harbor and Chenega, and would continue radiating outward from Alaska all night, barging down the coast. The water shattered a small town in British Columbia, wiped out a bridge in Washington State, and carried houses away in Oregon, as well as drowning four children who’d been camping on a beach there with their parents. The town of Crescent City, California, at the Oregon border, sustained a direct hit: a series of four waves, escalating into a monstrous wall of water, which leveled the downtown and killed 11 people. The wave action in the Pacific would still be ferocious enough, as it traveled south, to sink boats in a marina near San Francisco and damage a dock in Los Angeles—until, finally, 22-and-a-half hours later, the last of its energy petered out in a few four-foot-high swells slapping the banks of western Antarctica at the bottom of the world.

Genie first broadcast a tsunami alert for Anchorage an hour earlier and, since then, two fire trucks had been patrolling the city’s coastal neighborhoods, blasting orders to evacuate. Now a police dispatcher pressed Genie to warn Anchorage again; another radio station, he explained, had been mistakenly announcing that the danger had passed. Genie leaned into her microphone. “Please,” she warned, “any of you in the lowland areas, get out of the lowland areas and head for the hills! Please, don’t be overconfident!” There was pleading in her voice, as though, if she said it forcefully enough, it might repel that other, incorrect information off the airwaves.

Other times, when the station’s broadcasters clicked over to her for an update, she tried to smooth the frantic churn of announcements into something more conversational, interviewing more people who, like Major General Carroll, passed by her post in the building.

Each stunned, eyewitness account on the radio that night appeared to help people in Anchorage find the contours of this sinister abstraction they were living through— and to locate their places in it. For nearly five minutes, the earthquake had overpowered everyone. But now so many stories described people switching back on and spontaneously helping one another— reclaiming their roles, collectively, as protagonists in the disaster. “Anchorage has sustained a large amount of damage,” Genie would eventually tell her listeners, “and it’s been a shattering blow to a very proud people. However, many of us have enjoyed— actually, taken a great deal of pride in— seeing the way the people of Anchorage can rise to the occasion.”

Excerpt is adapted from This is Chance!: The Shaking of an All-American City, a Voice That Held it Together by Jon Mooallem, to be published by Random House on March 24, 2020

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.