The Coal Strike That Defined Theodore Roosevelt’s Presidency

To put an end to the standoff, the future progressive champion sought the help of a titan of business: J.P. Morgan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/66/1266ea09-9ec3-4f34-aa68-3685985fc01b/gettyimages-804459858.jpg)

The early morning whistles blew across Pennsylvania’s coal country on May 12, 1902. But 147,000 men and boys didn’t heed the summons to the mines. On that Monday they wouldn’t dig out the anthracite coal, or cart it above ground, or break it into pieces suitable for the homes, offices, factories, and railroads that depended on it. They wouldn’t show up on May 13 or the 162 days that followed.

The anthracite coal miners worked in dangerous conditions, were often underpaid and in debt, and knew the hardship to come. The coal barons expected to wait them out. The strike that began that May would become one of the greatest labor actions in American history. It was a confrontation between a past where power was concentrated and a future where it was shared, and it would define the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt had taken office eight months earlier, in September 1901, after President William McKinley was assassinated by a disgruntled former factory worker. Roosevelt retained McKinley’s cabinet, promised to follow his business-friendly policies, and accepted the counsel of McKinley’s closest advisor to “go slow.”

But not for long. In February 1902, Roosevelt’s attorney general, Philander Knox, announced that the Department of Justice would prosecute the railroad company just created by the nation’s most influential businessman for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. Northern Securities, a combination of three rail lines that dominated the Northwest, was now the second-biggest company in the world and its owner, John Pierpont Morgan, already controlled the biggest: United States Steel.

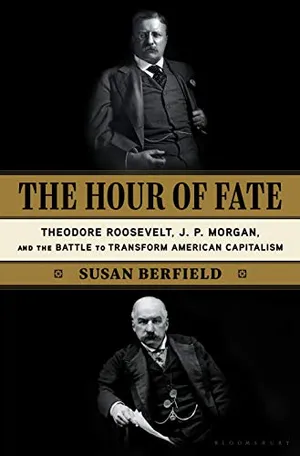

The Hour of Fate: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, and the Battle to Transform American Capitalism

A riveting narrative of Wall Street buccaneering, political intrigue, and two of American history's most colossal characters, struggling for mastery in an era of social upheaval and rampant inequality.

As the 20th century began, few people could avoid everyday encounters with monopolies: businesses trading oil, salt, meat, whiskey, starch, coal, tin, copper, lead, oil cloth, rope, school slate, envelopes and paper bags were pooled and combined and rarely held to account. Once settled in his new job, Roosevelt aimed to guarantee that, as America’s prosperity took hold, the laws applied to the country’s elite and its poor alike—to its agitated laborers, and its heralded capitalists. He wanted to assert the primacy of government over business.

A month into the coal strike—as railroads and factories began to conserve their coal supplies—it looked as though the President might get involved. Several people suggested how: just as Roosevelt and Knox had taken on Northern Securities, they could prosecute Morgan’s coal cartel for the same offense. (Morgan also controlled the most important railroads in Pennsylvania, which controlled the coal fields.) Or Roosevelt could ask the Board of Trade and Transportation to help resolve the strike.

George Perkins, a friend of Roosevelt’s and partner of Morgan’s, suggested Roosevelt do neither. Taking action would be a fatal mistake, he said. He told Roosevelt he was going to give Knox the same advice. No need. Knox had already come to the same conclusion. Roosevelt replied that he had no intention of doing anything just yet.

He did, though, send his labor secretary, Carroll Wright, to speak with leaders of the United Mine Workers, which organized the strike, and executives at the coal companies and suggest a compromise. But the coal barons rejected Wright’s recommendations and Roosevelt had no legal sway to enforce them.

Inaction always vexed Roosevelt. He was almost ready to test how far his presidential power would go.

Roosevelt wrote a note to Knox in August asking again why the government couldn’t challenge the legality of the coal cartel: “What is the reason we cannot proceed against the coal operators as being engaged in a trust? I ask because it is a question continually being asked of me.” The reason, Knox told him, again, is that the railroads had shrewdly organized the coal companies’ cooperation, making prosecution difficult under the Sherman Act. He wanted to wait for the ruling on the Northern Securities case before proceeding. Not the answer Roosevelt wanted. But he also knew that a legal solution, if there was one, would come too late.

By early September, the Washington Monument had run out of coal to operate its new electric elevator for the thousands of tourists who visited every month. Unscrupulous businessmen in cities throughout the Northeast and Midwest were buying most of the remaining supply and charging four times the normal price. The Post Office threatened to shut down, and public schools warned they might not be able to remain open past Thanksgiving.

Roosevelt was restless, fretful. He knew he would be blamed for remaining idle while Americans suffered. “Of course we have nothing whatever to do with this coal strike and no earthly responsibility for it. But the public at large will tend to visit on our heads responsibility for the shortage,” he wrote a friend.

Prices increased at laundries, bakeries, cafés, restaurants. Landlords raised the rent on apartments. Hotels charged more for rooms. Landowners sold their timber. In Chicago, residents tore out wooden paving from their streets to use as fuel. Railroads gave their employees old crossties to burn. Trolley lines limited service. Some manufacturers had to get by with sawdust in their furnaces. Pennsylvania steel mill owners said they might be forced to impose mass layoffs.

The president consulted governors and senators about how to bring the strike to a peaceful end. Their efforts yielded no results, though. The president heard from business leaders so desperate they proposed he take over the coal mines. “There is literally nothing, so far as I have yet been able to find out, which the national government has any power to do in the matter,” Roosevelt responded in a letter to Henry Cabot Lodge, a senator from Massachusetts and close friend. “That it would be a good thing to have national control, or at least supervision, over these big coal corporations, I am sure,” he wrote. “I am at my wits’ end how to proceed.”

Instead he had to rely on his moral authority. No president had ever shown much sympathy to workers on strike. Rutherford Hayes sent federal troops to quell a national railroad strike in 1877. Grover Cleveland sent troops to break the Pullman strike in 1894. But Roosevelt didn’t think coal country was in danger of erupting. He was more worried about a winter of misery, of sickness, starvation, and darkness. People might freeze to death; others could riot. He understood how panic could outrun reality.

The time had come for him to intervene directly. In early October, he invited the coal executives and the union leader, John Mitchell, to Washington in an attempt to mediate a settlement. Roosevelt appealed to the executives’ patriotism: “Meet the crying needs of the people.” They said they would—as soon as the miners capitulated. Later in the day, the president sternly asked again if they would consider trying to resolve the miners’ claims as operations resumed. They answered with a resounding no. No, they wouldn’t offer any other proposals. No, they wouldn’t ever come to a settlement with the union. No, they didn’t need the President to tell them how to manage their business. The conference was over.

“Well, I have tried and failed,” Roosevelt wrote that evening to Ohio Senator Mark Hanna, who earlier had also tried and failed to end the strike. “I would like to make a fairly radical experiment . . . I must now think very seriously of what the next move shall be. A coal famine in the winter is an awful ugly thing.” Nationalizing the coal mines would be a fairly radical experiment and an unprecedented expansion of presidential power.

The president mentioned his scheme to a leading Republican politician who responded with alarm: “What about the Constitution of the United States? What about seizing private property for public purposes without due process?” Roosevelt took hold of the man’s shoulder and almost shouted: “The Constitution was made for the people and not the people for the Constitution.” Then he let the rumor spread that he planned to take over the mines.

First, though, he made one final attempt to end the strike without force by turning to an unlikely solution: J.P. Morgan himself. They were fighting over Northern Securities in the courts and at odds over the very notion of a more expansive federal government. But now Morgan seemed to be the only one who could end the coal barons’ intransigence. They didn’t all owe their jobs to him, but if they lost his support, they wouldn’t last long. Morgan had hoped the matter would resolve itself, but he, too, was worried about a winter of disorder. He also feared that the public hostility toward the coal industry might spread to his other, more profitable, companies.

Morgan agreed to meet with Elihu Root, another former corporate lawyer and Roosevelt’s secretary of war. The financier and the president each trusted Root more than they trusted each other. Root joined Morgan on his yacht Corsair, anchored in the waters around Manhattan, on a Saturday in mid-October, and over five hours they drafted a plan that would end the strike and create an independent commission—appointed by Roosevelt—to hear the complaints of the mine owners and their employees. Morgan insisted the executives sign off on the compact, which they did. A few days later, the union leaders and the strikers did too. By the end of the month, the miners were back at work.

The Anthracite Coal Strike Commission convened in Pennsylvania in November, calling on miners, mine owners and union officials to publicly share their concerns and defend their demands. Their testimony continued through the winter. In March 1903, the commission’s report was published; its findings were final. The owners agreed the miners’ workday should be cut from ten to nine hours, and they awarded a retroactive 10 percent wage increase to the miners, admitting that a 10 percent price increase in coal was likely. The commissioners did not recognize the United Mine Workers’ union. That, they said, was beyond the scope of their mandate. But they stated that all workers had the right to join unions and that employers would ultimately benefit from collective bargaining. The commission created a permanent six-member board of conciliation to rule on disputes between the miners and their employers.

Both sides could, and did, consider the conclusions a victory. The union said it was pleased to win a wage increase. The coal executives said they were gratified that the union hadn’t won recognition. Roosevelt congratulated the commissioners and invited them to a dinner to celebrate their success.

The president knew that even as he had set a precedent for the federal government to get involved in labor disputes, he couldn’t have done so without the biggest of the titans: Morgan. In the moment—and even more so in the next years, as he pushed a progressive agenda —Roosevelt considered his intervention in the strike one of the great achievements of his presidency. He wrote Morgan a heartfelt note of thanks. Morgan apparently never sent a reply.

Susan Berfield is the author of The Hour of Fate: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, and the Battle to Transform American Capitalism and an investigative journalist at Bloomberg Businessweek and Bloomberg News.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.