When Steve Fossett Became the Magellan of the Skies

Ten years ago, the pioneering adventurer took off in pursuit of a new record in circumnavigation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/89/50897d65-375f-41ca-b549-01d6d348b2eb/mar2015_e01_nationaltreasure.jpg)

On February 28, 2005, temperatures hovered just above freezing on a late afternoon in Salina, Kansas. I stood on the tarmac as the world-record-breaking adventurer Steve Fossett prepared to take off in the single-occupant plane he had commissioned. Painted a vivid red, white and blue, the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer resembled a giant praying mantis, the wings spanning 114 feet, the head a huge jet engine, the body a claustrophobic 3- by 7-foot cockpit. (Today the plane resides in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Udvar-Hazy Center.)

In the GlobalFlyer, designed for maximum fuel storage and minimum weight, Fossett hoped to make the first solo circumnavigation of the globe without stopping or refueling. Every inch of the 4,000-pound catamaran-shaped plane was filled with fuel—18,000 pounds in 13 tanks, 82 percent of the plane’s weight. The crew called it the “flying gas tank.”

Fossett’s friend and the mission’s sponsor, Sir Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Galactic, was on hand, holding the hatch open for Fossett. “I’ll be back in a couple of days,” Fossett predicted lightly. Fossett hugged his wife, Peggy, gave the rest of us a thumbs up, touched the Boy Scout emblem painted next to the cockpit as a good-luck gesture and crouched to enter. Branson sealed the hatch. A shuttle bus transported us to the end of the two-mile runway as Fossett prepared for takeoff.

GlobalFlyer raced toward us down the runway, gaining speed, thundering like an avalanche as Fossett lifted off. The plane roared overhead—only to dip sharply, as if it were going to crash. A split second later, the aircraft righted itself, catapulted into the dusk, headed east and disappeared. It would maintain an altitude of about 45,000 feet for most of the flight.

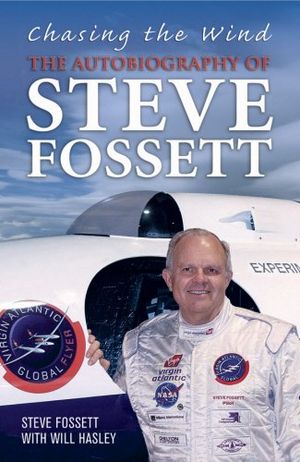

At the time, Fossett and I were collaborating on his memoir, Chasing the Wind. I later asked him about the moment when it looked to everyone as if the plane was going down. “I didn’t mean to scare anyone,” Fossett told me. “I was just leveling off so that I could ascend faster. The GlobalFlyer had never taken off carrying this much weight.” Fossett had been concerned, he recalled, “that the wings might dislodge on takeoff from the weight of the fuel. When I hit the last marker on the runway, I pulled back hard on the throttle and surged upward. I was alive! Thrilled and on my way!”

No sooner had Fossett taken off, however, than a series of potentially catastrophic problems surfaced—a temporary failure of the GPS navigation system, a fuel leak, a total loss of the backup oxygen supply essential to survive any steep emergency descent.

Despite the risk, Fossett insisted on continuing. Cooperative tail winds pushed him back to Salina faster than he had anticipated. At 1:37 on the afternoon of March 3, after being aloft for 67 hours, he landed. A marching band played. Thousands of people cheered. Journalists from around the world had camped out to report on his return. A wobbly Fossett climbed out of the cockpit, hugged his wife and shouted to the crowd: “This was a big one!” Branson dashed up with a bottle of champagne.

Fate finally caught up with Fossett, on September 3, 2007. He took off alone on a pleasure jaunt in a single-engine, two-seat plane about 90 miles southeast of Reno, Nevada. His disappearance launched a massively intensive and expensive search and instigated one of the first crowdsourced attempts to locate a missing person by scouring satellite images. Thirteen months later, the wreckage at last was pinpointed after a hiker discovered Fossett’s aviation license in a ziplock bag near Mammoth, California.

But on that heady night when Fossett returned to Salina, Branson offered the tribute that would define his friend: “He is the adventurer’s adventurer.”

Related Reads

Chasing the Wind: The Autobiography of Steve Fossett