A towering Muppet with shaggy blue fur and a bulbous orange nose bursts through the doors of an animated schoolhouse, plops his oversized sneakers onto a skateboard and joins a gaggle of children racing to Ulitsa Sezam—“Sesame Street” in Russian. The creature’s name is Zeliboba, and he greets young viewers in the opening sequence of this foreign-language adaptation of the iconic American children’s show.

As the title scene continues, audiences see kids playing soccer, fishing and riding on a horse-drawn carriage piled high with hay—a nod to the rural culture of the former Soviet Union. The children jump into a hot air balloon and sail into the sky with Zeliboba and two other Muppet pals, Kubik and Businka. All the while, a jaunty tune plays, promising wonder and adventure:

In the world—there’s so much interesting,

Completely unknown.

You’ll discover this for yourself

On Sesame Street, on Sesame Street.

“Ulitsa Sezam” bounded onto TV screens across the former Soviet Union in October 1996, nearly five years after the collapse of the U.S.S.R. It was a complicated era, simultaneously fraught with instability and rife with the hope that a new generation of children would grow up in a freer society than the one that had preceded it. Helmed by the Children’s Television Workshop, the American organization behind “Sesame Street,” “Ulitsa Sezam” sought to teach young viewers the skills they would need to thrive in a nascent market economy, with Muppets serving as fluffy mascots of democratic values.

From the Soviet collapse to “Sesame Street”

The “Sesame Street” spinoff set out to be the first Russian-language educational TV program aimed specifically at preschoolers. The project received support from both American and Russian government officials. “If we do not reform our education, we can hardly hope that we will reform our society,” said Elena Lenskaya, a director in Russia’s Ministry of Education, during a 1992 U.S. congressional hearing on the planned adaptation.

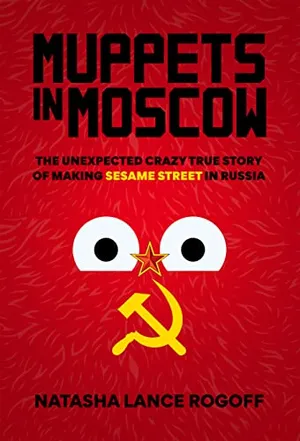

Yet the co-production endured a relentless slew of challenges, including financing woes, the invasion of its offices by armed soldiers and thorny conflicts as the cheery ethos and bold aesthetic of “Sesame Street” ran headlong into Russia’s rich, but markedly different, cultural traditions. Time and again, “Ulitsa Sezam” had to be salvaged from the brink of collapse by passionate teams on both sides of the Atlantic. It’s a tumultuous tale lovingly chronicled in Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia, a new book by American journalist, TV producer and filmmaker Natasha Lance Rogoff.

Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia

More than just a story of a children’s show, this book provides a valuable perspective of Russia’s people, their culture, and their complicated relationship with the West that remains relevant even today.

The Children’s Television Workshop (CTW)—now known as Sesame Workshop—recruited Rogoff to executive produce “Ulitsa Sezam” in 1993. Since her days reading Gogol and Dostoyevsky in high school, Rogoff had been enthralled by Russia. “I just thought that these writers were speaking to me,” she says.

In college, Rogoff moved to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) as an exchange student, ultimately becoming fluent in the Russian language. She spent more than ten years in the region, reporting for NBC News and CBS News, and illuminating life in the Soviet Union with documentaries like 1985’s “Rock Around the Kremlin,” which explored the underground Russian rock scene. She stayed in Moscow after the U.S.S.R.’s collapse to direct “Russia for Sale: The Rough Road to Capitalism,” a documentary spotlighting the struggles of everyday citizens during a period of great flux.

Though she had ample experience working in Russia, the job offer from the CTW gave Rogoff pause. She had never produced a kids’ television series, for one. She also wondered whether fuzzy cast of monsters on “Sesame Street,” beloved by American little ones, would similarly resonate with children of the former U.S.S.R.

Within weeks of its premiere on November 10, 1969, the original “Sesame Street” had become a “cultural phenomenon,” according to the New Yorker. The series was created by Joan Ganz Cooney, a producer for New York public television who hoped to use TV as a medium for educating young children and preparing them for elementary school—a novel idea at the time. Aimed at children from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, “Sesame Street” was rooted in specific learning objectives shaped by a multidisciplinary group of experts. The show also featured a diverse, integrated cast, deliberately challenging the marginalization of Black Americans then prevalent both on television and in society.

The first international “Sesame Street” co-production launched in 1972, with Brazil’s “Vila Sésamo.” To date, some 30 countries around the globe have created their own version of the series. International adaptations are “developed in partnership with local production houses, governments and educators,” per NBC News, and care is taken to address the specific needs of the region hosting the show. For example, South Africa’s “Takalani Sesame,” which debuted in 2000, later introduced an HIV-positive Muppet in an effort to combat stigma and discrimination in a country with high HIV prevalence.

In 1973, a Soviet Communist Party newspaper denounced the international expansion of “Sesame Street” as “a clear example of veiled neocolonialism in cultures.” But the fall of the Soviet Union opened the doors to cultural exchange with the West—and the chance to participate in this heady era of transition proved “too enticing” to Rogoff. “To have the empire suddenly implode and then have this opportunity to create a program that would bring new skills and new ideas to children across the whole former Soviet Union was just an incredible opportunity,” she says.

There was another reason that Rogoff agreed to take the job: “I didn’t anticipate the level of difficulty that we’d have, or the dangers that we’d face.”

The fall of an empire

During the seven decades of its existence, the Soviet Union grew to encompass 15 republics across Europe and Asia, becoming one of the world’s most powerful nations. But when the fall of the empire arrived, it came quickly.

In the late 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev, a Communist Party leader, attempted to overhaul the country’s inert bureaucracy and sluggish economy through two key platforms: glasnost, or “openness,” which eased repressive censorship policies, and perestroika, or “restructuring,” which incorporated a degree of market economy principles into the Soviet economy by loosening price controls and encouraging limited private businesses, among other measures.

This move to invigorate the nation through transparency and reform “brings up fresh ideas of how to run state enterprises better. It involves people in politics again,” says Juliane Fürst, a historian at the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History in Germany. But Gorbachev’s policies also opened the door to disarming revelations about the Soviet regime’s inefficiencies, corruption and long history of atrocities. “Basically, everything starts to accelerate,” Fürst explains, “to such an extent that the state completely loses control.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d6/75/d6758163-77b9-4e32-b105-dd60a0204f5a/the_live_ring_campaign_around_the_kgb_building_in_moscow.jpeg)

Boris Yeltsin, an advocate of democracy and market economies, emerged as the nation’s most important political player. By December 1991, the Soviet Union had collapsed, with Yeltsin at the head of an independent Russia. But “vaguely outlined goals—democracy, market economy, national rights—gave little guidance” at the dawn of this new era, writes historian Ronald Grigor Suny in The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the U.S.S.R. and the Successor States.

When it came to the economy, Russian officials opted for an aggressive approach, lifting price controls on most items—which led to soaring inflation—and implementing the mass privatization of enterprises that had once been controlled by the state. The government introduced a voucher system that allowed Russian citizens to buy shares in former state industries, but it was a complex scheme that benefited few ordinary people. The economy “went into a tailspin,” Suny writes, and “for the bulk of people, poverty [became] the norm.” A few resourceful individuals, however, made their fortunes buying up newly privatized businesses—including television stations. “To many Russians,” notes Encyclopedia Britannica, “it seemed that bandit capitalism had emerged.”

Economic challenges during this period were compounded by a rise in crime that the state was unable to suppress. “Corruption was widespread,” according to Suny. “The rule of law, which had been one of the initial goals of perestroika, continued to elude the Russian political system.”

Adapting “Sesame Street” for a new audience

Into this turbulent landscape came “Sesame Street” and its mission of bringing “sunny days” to former Soviet nations. But the confounding, sometimes perilous nature of conducting business in Russia was consistently made clear—starting with Rogoff’s efforts to find a Russian broadcast partner to supplement American government funding for “Ulitsa Sezam.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/7d/fa7dbaaf-6898-4b9a-8fdf-a9daa044811e/p22.jpg)

On the ground in Moscow, Rogoff and journalist Leonid Zagalsky secured an offer from Boris Berezovsky, an oligarch who owned part of a leading Russian television network. “Only someone like Berezovsky, with his shady connections, could possibly bankroll a big production like ours,” Rogoff recalls Zagalsky telling her. But the arrangement fell through after Berezovsky’s car was bombed in a failed assassination attempt. Later, “Ulitsa Sezam” found a supporter in Vladislav Listyev, a beloved television journalist and executive who sought to purge his television network of corruption. He was murdered shortly after promising to help broadcast the show.

Danger arrived on the production’s doorstep when its offices were raided by soldiers toting AK-47s, who, for reasons that remain unclear to Rogoff, confiscated scripts, equipment and set designs—even a life-size Elmo that served as the office mascot. In Muppets in Moscow, Rogoff writes that one of the show’s producers planted herself between the soldiers’ weapons and a fax machine so she could finish sending the budget for “Ulitsa Sezam” to the CTW. Another member of the team tried to rescue Elmo, but the soldier who grabbed the Muppet seemed keen to hang on.

Nearly three decades after these incidents, Rogoff remains full of admiration for the television workers who persisted through trying conditions to bring “Ulitsa Sezam” to life. They “were brave people,” she says, “who were committed to creating a better future for Russia’s children and an open society.” But Rogoff and her colleagues didn’t always coalesce without friction. As she writes in her book, “cultural battles … touched almost every aspect of the show.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f7/e6/f7e6805a-0b13-4436-a0aa-2d73d4a12caa/p15.jpg)

The CTW made sincere efforts to ground “Ulitsa Sezam” in the culture of its target audience. All of the show’s original production was based in Moscow (around 40 percent of the series consisted of segments from the American show, dubbed into Russian); episodes featured the work of Russian artists, composers, scriptwriters, puppeteers and actors. Educators were recruited from across Russia and several former Soviet republics to shape the show’s educational framework. Still, Rogoff often found herself wrangling with colleagues over ideas that simply didn’t align with the “Sesame Street” brand.

According to Rogoff, the team fought “tremendous battles” over the music director’s insistence that “Ulitsa Sezam” include only classical music, citing Russia’s “world-renowned” classical music tradition. “One of the great features of most of our ‘Sesame Street’ programs around the world is diverse, innovative music written for a comedy show,” Rogoff explains. “This argument took several months [to resolve].”

Even the Muppets, icons of “Sesame Street” and so endearing to American eyes, became a source of contention. The show’s Russian producers found the monsters “too strange-looking,” Rogoff writes—and too naked. They suggested that “Ulitsa Sezam” instead feature wooden puppets modeled after traditional characters from Russian puppet theater. As one producer told Rogoff, “Russia has a long, rich and revered puppet tradition dating to the 16th century. We don’t need your American ‘Moppets’ in our children’s show.”

Despite its good-faith intentions, the “Ulitsa Sezam” project collided with a robust legacy of Russian artistry, including “a really rich and very charming” children’s TV culture, says Christine Evans, a historian at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the author of Between Truth and Time: A History of Soviet Central Television. Politically driven programs showing children participating in state youth organizations, among other activities, made up some of the Soviet broadcast lineup. But there were alternative options for young viewers, too, like the “Mister Rogers”-esque “Good Night, Little Ones!” and “beautiful, melancholy and spiritual cartoons,” Evans says.

She cites, as an example, the famed cartoons of Yuri Norstein, described in 2005 by the Washington Post as “not just the best animator of his era, but the best of all time.” The animals in his films, which aired on TV, “are very kind, and they think very seriously about life,” Evans says. “There are moral values that might not be so different [from] what ‘Sesame Street’ was about promoting: caring for one’s peers, being polite and respectful, kindness.”

Still, adds Evans, the visuals of “Sesame Street” were “different and distinctive” from what Rogoff’s Russian colleagues were accustomed to seeing on TV. The post-Soviet period was a difficult time of transition for television workers, who were “fairly high prestige” in the socialist state, the historian explains. “Then the ’90s hit, they lose the state’s funding for culture and media collapses.” Professionals who had been leading comfortable lives and considered themselves cultural leaders suddenly struggled to make ends meet.

“You can see the affront it represents to say, ‘Let us teach you about puppets,’ even though that wasn’t the intention, presumably,” Evans adds.

By her own description, Rogoff’s previous experience as a journalist and documentarian had positioned her as “an observer” of Soviet society. She soon realized that “Ulitsa Sezam” required a different approach, one that was more deeply immersed in the region’s history and culture. “If we were attempting to promote progressive values and encourage openness in the society,” she says, “we would have to take into consideration Russia’s past and how Russians wanted to educate their children in the future.”

The legacy of “Ulitsa Sezam”

When “Ulitsa Sezam” made its debut in 1996, it was a distinctly “Sesame Street” creation with a uniquely Russian flair. The show featured three new Muppets designed by the Jim Henson Company but shaped by the input of the Russian team. Zeliboba, for instance, was a forest creature who lived in a large treehouse, nestled into a canopy of six-pointed leaves resembling the foliage of oak trees in Russia. Contemporary musicians contributed original melodies to the show, but Katya, one of the series’ human characters, was especially fond of classical music. The cast also included actors representing ethnic minorities from across the former Soviet Union, modeling diversity in a region beset by ethnic conflicts.

“Ulitsa Sezam” stayed true to its educational objectives, using fun-loving Muppets to teach valuable skills for life in a market economy. Rogoff fondly recalls a scene centered on politeness. At a local bakery, Zeliboba holds the door open for Aunt Dasha, a human character. Aunt Dasha praises him for being polite, which so tickles Zeliboba that every time she tries to leave the shop, he closes the door and reopens it. Many “pleases,” “thank-yous” and “you’re-welcomes” are sprinkled throughout the exchange.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/c6/8dc6e712-d8ab-4500-a27a-194ec70ad0d0/p17.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/d0/f4d05744-cd60-407f-b808-b3f02e8ecd58/p17_copy.jpg)

Rogoff left the CTW in 1998, but “Ulitsa Sezam” stayed on the air until 2010, when it lost support from “[Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s people at the television networks,” according to Muppets in Moscow. Hopeful visions of a democratic, open society in Russia—visions that gave rise to “Ulitsa Sezam” and propelled it through challenging moments—ultimately failed to materialize. Relations between Russia and the West have deteriorated, with the war in Ukraine exacerbating Russia’s fraught position on the world stage.

Even amid forces too great for one Muppet (or three) to change, Rogoff believes “Ulitsa Sezam” made an impact. She recalls receiving thousands of fan letters, including one from a girl who wrote, “I love ‘Ulitsa Sezam,’ and especially love Zeliboba, because he’s not afraid to make mistakes.” The note lingers in Rogoff’s mind as a testament to the strength of the show’s messaging, which encouraged values like curiosity, fallibility and free expression.

“Ulitsa Sezam” also exuded a “warm, open, friendly” feel during times that were often destabilizing and difficult. “I wasn’t naive,” says Rogoff of the harsh reality of life in 1990s Russia. “But I hoped that there were people who could change it. I hoped that our show would contribute to that change, and I believe it did.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/6d/d86def4b-5466-4ad7-97a0-2cf718cc4b28/gettyimages-1186286231.jpg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(815x590:816x591)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/82/9c824442-8422-4a9f-97b9-f347dcc8700a/p23.jpg)