On the night of May 27, 1754, Lt. Col. George Washington led a party of Virginia soldiers out of an encampment in the Ohio Valley. The conditions were horrid—a night “as black as pitch,” as the young commander recorded in his journal. An unceasing rain made the dark woods even more impervious to the soldiers and warriors.

Washington was only 22 years old, his mouth still full of teeth. The uniform he wore was likely a woolen officer’s coat showing his allegiance to the British empire—he was a loyal subject of King George II. He and his Virginia Regiment of a little over 100 effective soldiers were the tip of His Majesty’s spear in North America. Their assignment: to finish building a fort that would anchor Britain’s control over the Ohio Valley.

But as Washington and his men marched westward over the Appalachian Mountains, they received stunning news: The French had already captured their intended destination, known as Trent’s Fort. Hundreds of French troops had aimed over a dozen cannons at the British soldiers stationed there and forced their surrender.

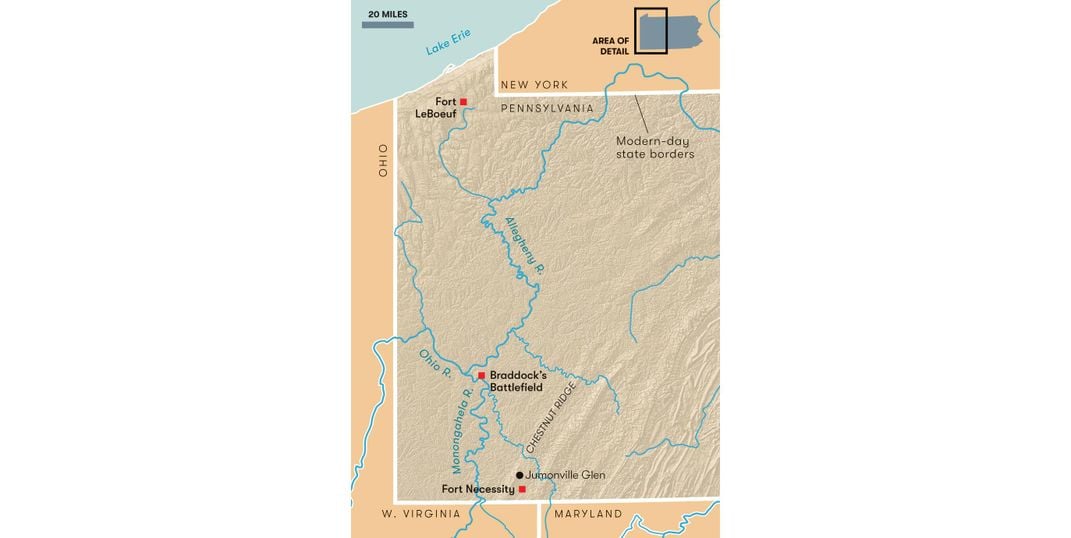

By May 24, Washington had encamped at the Great Meadows, one of the few open clearings amid the dark Appalachian woods. There he received word from a man named Tanaghrisson, an Ohio Iroquois, that an army of French soldiers was coming to attack his men. French tracks were spotted only five miles from the camp, and Washington sent out 75 of his best soldiers to search for the French party. Then his Indian allies found the spot where the French were camping, hidden in a glen near the crest of a mountain ridge.

On May 27, the men who remained with Washington—a small party of 40 British soldiers and perhaps seven or eight Ohio Iroquois allies—marched five miles and climbed 700 feet up the steep eastern face of Chestnut Ridge. Seven soldiers got lost as they stumbled in the rain over the ridgeline’s many rocks, spurs and draws. By the time the remaining 33 men crested the ridge, they were exhausted and soaked.

As the sun began to rise, the soldiers struggled to operate their muskets amid the lingering dampness. It was around 7 a.m. on May 28 when the Virginians, advancing in single file, came to the rocky precipice overlooking the French camp. Washington was at the head of the column and the first to spot the French who, he later reported, scrambled for their muskets.

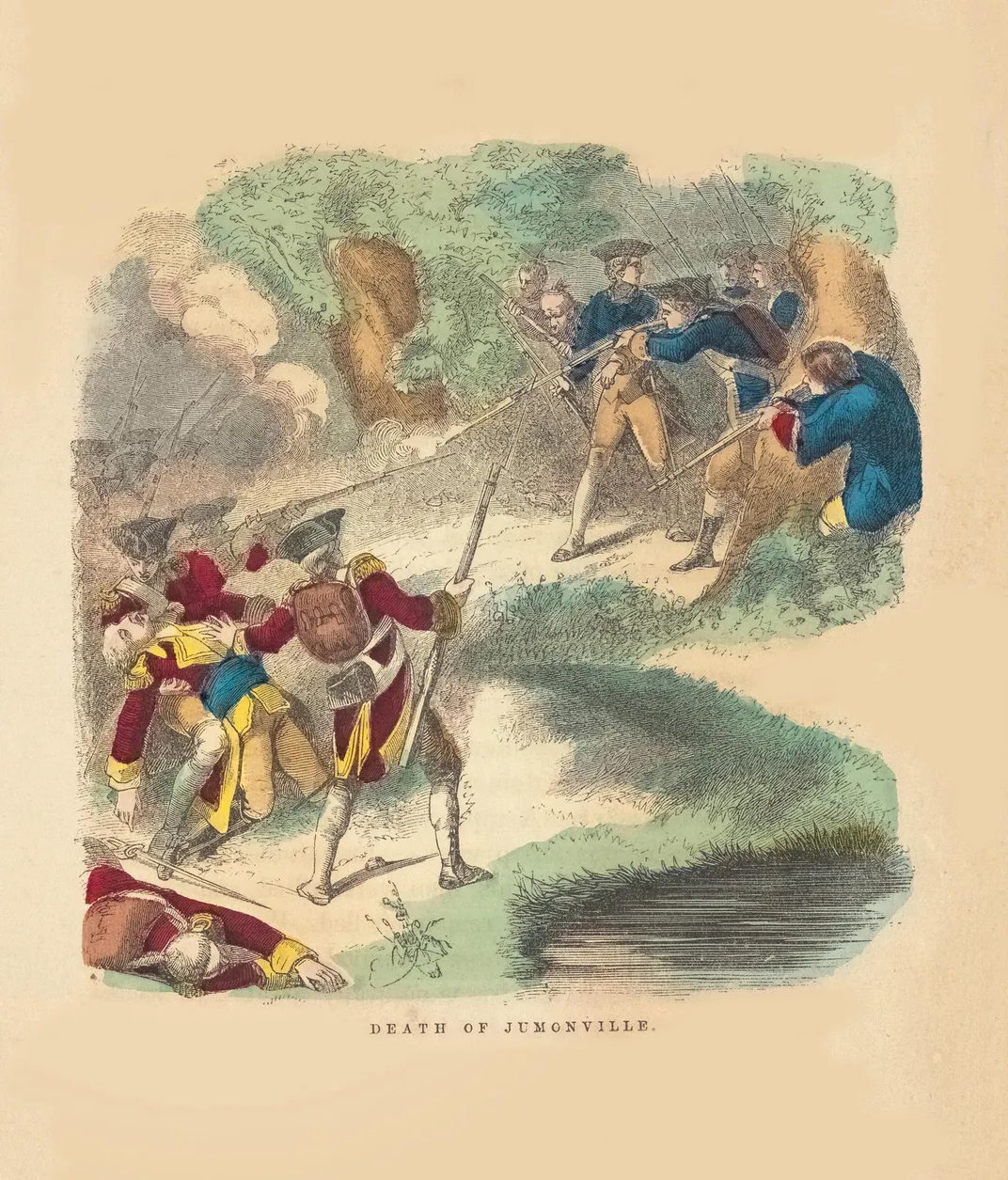

The battle lasted only 15 minutes. At least ten French soldiers fell, most of them killed by Washington’s Indian allies. One of those dead Frenchmen was the party’s commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. The mountain glen was a macabre scene of unburied and scalped French corpses, with a Frenchman’s decapitated head stuck upon a pole.

Historians have long identified this skirmish in the woods as the spark that ignited the French and Indian War. But there’s an untold dimension to this story, as I discovered several years ago, digging through colonial papers in the British National Archives. This evidence, previously unreported, suggests that the man who would become America’s first president might have been more complicated a leader—and more culpable for starting a seven-year-long global war—than history has led us to believe.

* * *

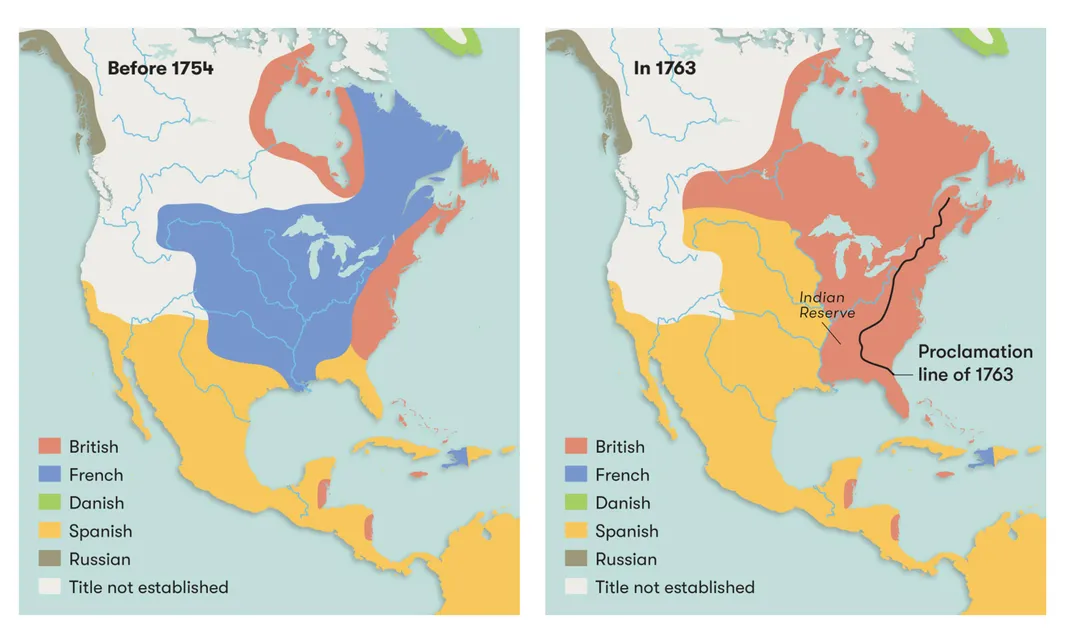

The French and Indian War is one of those conflicts we learned about in history classes, but we tend to be hazy on the details. That’s partly because it all took place a generation before the Revolutionary War, a time most Americans don’t think much about. It’s also because the name is a bit confusing: It was a conflict between British and French colonists, with Indian nations as allies on both sides. Back then, the colonists on the Atlantic seaboard were still loyal to Britain. French influence extended far inland, and it was starting to expand into the Ohio Valley, edging into Pennsylvania. The British had more people and resources, but the French had access to important waterways, including the Great Lakes and the Mississippi. As the French philosopher Voltaire wrote around the time of the Jumonville affair: “So complicated are the political interests of the present times that a shot fired in America shall be the signal for setting all Europe together by the ears.”

At that time, the Indians in the Ohio Valley were still independent and powerful, and both sides needed them as military and trading partners. The French had cultivated a broad network of Indian alliances by the 1740s. In response, the British tried to inflate the power of the Six Nations—the Iroquois Confederacy that dominated much of the Northeast. In particular, they elevated an Ohio Iroquois leader named Tanaghrisson, treating him as a spokesman for all the Ohio nations. The British dubbed Tanaghrisson the “Half King.” Yet he didn’t actually speak for all the Ohio Indians. He’d come on the scene only in the late 1740s and his role was never recognized by the French, who thought him “more English than the English.”

In the summer of 1753, the French started acting more brazenly. They sent 2,600 soldiers into the region, building a fort on the shore of Lake Erie and another at the headwaters of nearby Le-Boeuf Creek. Both the British officials in Virginia and their Indian allies in Ohio were alarmed.

That’s when Washington walked onto the stage of history. At the end of 1753, Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie asked him to lead a diplomatic expedition to warn the French to leave their forts. Washington had been in the militia less than a year, but he’d worked as a surveyor starting at the age of 16, and the governor knew this experience would help him navigate the frontier as he led the 500-mile trek from Williamsburg, Virginia, to Fort LeBoeuf.

The group reached Fort Le-Boeuf on December 11, 1753, accompanied by Tanaghrisson and other Ohio Indians. The French commandant received the party with great civility, even sent them home with supplies, but he rebuffed Governor Dinwiddie’s demands. Still, Washington’s journey had allowed him to gather valuable intelligence: He’d learned that the French were assembling a flotilla of small boats to carry them to the Forks of the Ohio, where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers met to form the Ohio River, and where the British planned to build a small but strategic fort.

After Washington returned, his journal of the expedition was published in Williamsburg and London, spreading the young officer’s fame. In early 1754, Dinwiddie promoted him to second in command of the Virginia Regiment—and sent him back to the Ohio Valley, this time to complete the fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Although he wasn’t instructed to start a war, he had the authority to restrain any French interlopers and, if necessary, “kill & destroy” them.

Following the May 28 battle, when French officials learned that Ensign Jumonville had been killed by British colonists and their Indian supporters, their anger boiled over. According to French accounts, Jumonville and his men were preparing to deliver a diplomatic summons to the British, not take up arms against them. In fact, they insisted, Jumonville had tried to get the British to stop firing so he could speak to them. One report even claimed that Jumonville had been shot through the head while one of his fellow soldiers was in the process of reading a message to the British. The French portrayed Washington’s ambush as the brutal murder of a diplomatic official.

Some sources—including a British newspaper—reported that Tanaghrisson himself had killed Jumonville. One telling of that story, by a British deserter, added an especially brutal twist: As Jumonville lay wounded after the battle, Tanaghrisson approached him and remarked, “Tu n’es pas encore mort, mon père”—“You are not yet dead, my father.” He lifted his tomahawk and planted the blade in Jumonville’s skull.

Centuries later, it’s still not clear who is to blame for the bloody incident. Had the French been planning to attack the British all along? Or had the British opened fire hastily, or been manipulated by their Indian allies? Dinwiddie, for his part, had always blamed his Indian allies for starting the whole thing, telling his superiors back in London: “This little Skirmish was by the Half-King & their Indians, we were as auxiliaries to them.”

A few years ago, I was sitting in the sprawling reading room of the British National Archives in Kew. The enormous bound volume on the table before me was part of a collection called the Colonial Office papers. This trove of colonial documents included official correspondences, maps, legal and military records, and Indian treaties.

I was intrigued by the location and date of one document in particular: It was entitled “A Treaty with the Indians at Camp Mount Pleasant October 18th 1754.” Camp Mount Pleasant was a British outpost along the upper Potomac River in what is now western Maryland. In the fall of 1754, a group of British Army officers gathered there with Ohio Iroquois, Delaware and Shawnee leaders to renew their alliance and hear their grievances. Through an interpreter, a British scribe recorded the Indians’ speeches word-for-word with quill and ink over a total of ten pages.

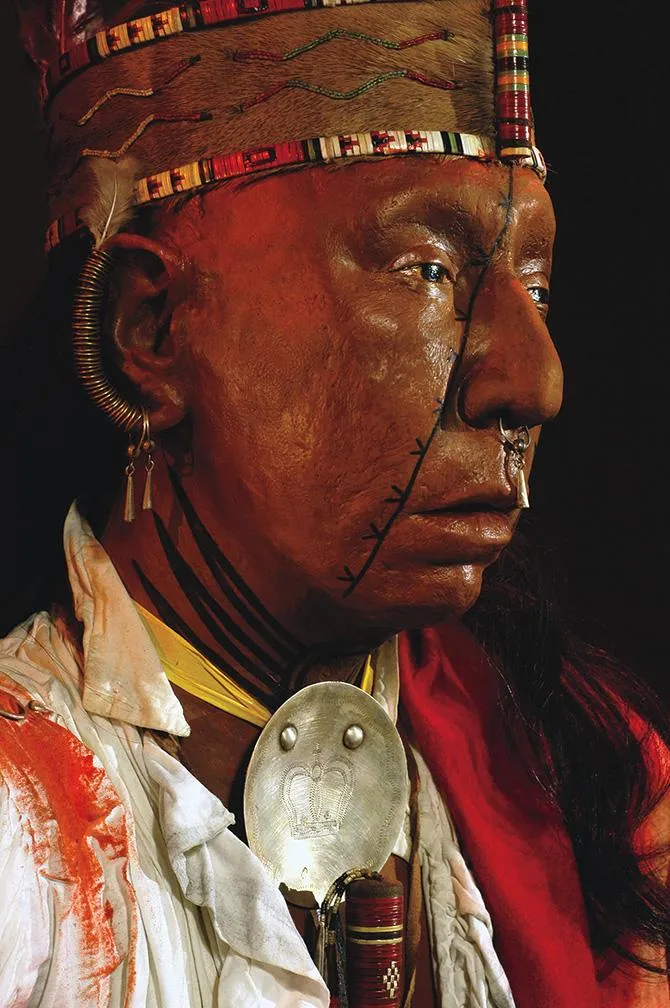

One speech had been delivered by a man identified as a “Chief Warrior” of the Ohio Iroquois. The French had driven the chief warrior and his people from their lands in the Ohio Valley, and they were now living as refugees among the British. The chief warrior began bluntly, telling the British officers: “We are all Soldiers and Warriors. Some sharp words will now pass between us. We shall talk like drunken Men.”

Those “sharp words” turned into an extended account of the major events that had brought them to their current crisis—from Washington’s 1753 diplomatic mission to the French conquest of the Forks of the Ohio River and the Jumonville affair. Hidden in plain sight was a new document pertaining to none other than George Washington and the Indian allies who had supported him.

Not believing my good fortune, I went back to the existing histories and confirmed that this October 1754 treaty had never been transcribed, analyzed or even cited by previous scholars writing on Washington and the Jumonville affair. It provided a rare eyewitness account of the opening scenes of the French and Indian War.

Who was this “Chief Warrior”? The treaty minutes provide no clues, other than that he was known “to have a true Heart” to the British alliance. Perhaps the speaker was Kanuksusy, a Seneca man whom Washington had once described as a “great Warrior.” Or perhaps it was Silver Heels, who went on to one of the most remarkable British military careers of any Indian warrior, fighting with distinction in the Ohio Valley, New York, South Carolina and even on the West Indies island of Martinique.

The chief warrior voiced his suspicion that “the King of England and the French King had made an Agreement to cut us off”—that both European powers were conspiring to divide and conquer the Indians. As the chief warrior told the British, certain events and revelations had “given us some Reason to suspect you.”

The chief warrior then described his own involvement in the Jumonville affair. The young George Washington he described was neither a valiant hero nor a bloodthirsty aggressor. Instead, he was an earnest but headstrong 22-year-old who, simply put, wasn’t very good at cultivating allies.

History Lesson

The chief warrior complained that after he and his fellow Ohio Iroquois escorted Washington from their encampment in Logstown to Fort LeBoeuf in 1753, Washington “left us there, came through the Woods, and never thought it worth his while to come to Logs Town, or near us and give us any Account of the Speeches that passed between him and the French at the Fort which he promised to do.” Washington had seemed more interested in making his report to Governor Dinwiddie than cultivating Indian allies.

The chief warrior had also witnessed the French takeover of Trent’s Fort in April 1754. He reported that the British had surrendered meekly in the face of 600 French marines and militia—the largest European military force that had yet been seen in the Ohio River Valley. But the chief warrior noted that Tanaghrisson, the “Half King,” had tried to stir up conflict during the surrender, warning the French not to trespass on Ohio Iroquois lands, where he had given permission for the English to build a trading post. Tanaghrisson had even pushed a French officer, and “a Scuffle” ensued. If cooler heads had not prevailed, the chief warrior told the group, “they would not have left one Frenchman alive upon the spot.”

This telling of the story offers an important new angle on the origins of the Jumonville affair. It indicates that the French had humiliated Tanaghrisson, dealing with him as an English puppet and exposing his lack of influence. After the incident, Tanaghrisson’s band of 80 to 100 men, women and children had fled the area, taking refuge with their British allies to the east. Tanaghrisson had a vendetta against a particular French officer named Michel Pépin, also known as La Force. Only a few weeks earlier, La Force had spoken at Tanaghrisson’s settlement of Logstown, threatening his band of Ohio Iroquois that “You have but a short Time to see the Sun, for in Twenty Days You and Your Brothers the English shall all die.” By the end of May 1754, when Tanaghrisson reported to Washington that a French “armey” was on its way to “strike the first English they see,” Tanaghrisson believed that the French—especially the feared La Force—were plotting to kill him and his followers.

The three parties met amid a perfect storm of misunderstandings. The Ohio Iroquois band believed they were being pursued by the French. The French considered themselves diplomats, delivering a summons to the British to leave French lands—much like the summons Washington had delivered to the French some months earlier. And the British were advancing with the information they’d gathered from Tanaghrisson and others, believing the French were coming for them with violent intentions.

When it comes to the battle itself, the chief warrior’s account surpasses all other eyewitness accounts in its level of tactical detail. In particular, no other account provides as much insight on how Indian warriors guided the young Washington in his first combat action—an ambush. The Indians directed him to “go up the Hill, straight to the French where they were, not above fifty Yards off, when they must come in Sight of the French Camp below them.”

While the warriors sent the Virginian toward the rocky precipice, the Indians descended into the hollow: “The Half King with his Warriors went to the left to intercept them if they should go that Way, and Monacatootha with another young Warrior Cherokee Jack went to the Right.”

One line from the chief warrior’s speech struck me above all others: “Col. Washington begun himself and fired and then his people.” Washington himself always took responsibility for ordering his company to open fire, but the chief warrior’s report takes this even further, claiming that Washington literally fired the first shot. Perhaps it was a signal to his soldiers and his Indian allies to commence the attack, or perhaps he was taking aim at a French adversary. Either way, if true, it heightens Washington’s moral responsibility in the whole affair.

The chief warrior contended that the French traded volleys with the English, “two or three Fires of as many Pieces as would go off, being rainy Weather.” The French “having taken to their Heels and running, happening to run the Way the Half King was with his Warriors, eight of them met with their Destiny by the Indian Tomayhawks.” The stunned French survivors fled back in the opposite direction, only to run headlong into Monacatootha and Cherokee Jack, who presented the prisoners to Washington, adding that “we had blooded the Edge of his Hatchet a little.”

One Frenchman, named Monceau, managed to slip into the woods and spread news of the skirmish. The rest were now prisoners huddled near the British, hoping that they would not be tomahawked. Three Virginians were wounded—a strong indication that the French had managed to return fire earlier in the battle. One Virginian had been killed.

The chief warrior, however, revealed what Washington failed to report about one of his casualties—that the Virginians “unluckily shot their own Man,” who had gotten ahead of their lines in the chaos of battle.

The chief warrior’s account mentions La Force numerous times, but never Ensign Jumonville—an omission that supports the notion that the Iroquois were more focused on the hated La Force. His account also says nothing of the French reading any summons. It does relate that the Half King angrily shouted at La Force: “You came after me to take my Life and my Children.” He then raised his tomahawk over La Force, declaring, “Now I will let you see that the Six Nations can kill as well as the French.” But according to the chief warrior, La Force took refuge behind Washington, who “interposed” and prevented his death.

Immediately following the skirmish, Tanaghrisson sent French scalps to various Native groups to announce his deed. But if Tanaghrisson had expected this to somehow galvanize Ohio Indians against the French and restore his own authority, he had woefully misjudged the geopolitics of the entire Ohio Valley. By 1754, Ohio Shawnees had already declared “perpetual war” against the English, while other Delaware and Iroquois bands were firmly committed to the French alliance.

The chief warrior’s speech also described what happened after the battle. Washington and his men eventually returned to the Great Meadows, where they began building a fort. According to the chief warrior, Tanaghrisson had encouraged Washington to fortify elsewhere. No Indian warrior wanted to fight a European-style battle in what Tanaghrisson called “that little thing upon the Meadow.” But Washington had few options.

On July 3, 1754, Fort Necessity, as it was called, was attacked by a group of 600 Frenchmen and about 100 of their Indian allies seeking vengeance. The group’s commander, Capt. Louis Coulon de Villiers, was Jumonville’s older brother. Washington’s side suffered severe casualties. The British accepted French terms for an honorable surrender of the post.

Or so they thought. Washington missed important language in the surrender document: It stated that Villiers and his men had acted only to avenge Jumonville’s “assassination.” In the pouring rain and darkness, Washington’s translator provided a faulty translation of the document. Washington maintained that he never would have signed it had he known of that charge, but the political damage was done.

The Ohio Iroquois allies were absent for all of this; by that time, they had become thoroughly disappointed with their British allies. Following Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity, some Ohio Iroquois took refuge on the Pennsylvania frontier, while other prodigals returned to their French father in due time. The chief warrior left an unflattering portrait of Washington as a leader who “never consulted with us nor yet to take our Advice.” Tanaghrisson also described Washington as a “good-natured man but had no Experience,” complaining that the young Virginian “took upon him to command the Indians as his Slaves.”

* * *

News of Washington’s defeat broke like a thunderclap when it reached imperial officials in London in August 1754. The British government intervened by sending Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock with two regiments of regular troops to accomplish what the colonists could not. But Braddock requested that Washington serve as an aide.

In July 1755, Washington had the chance to reclaim his reputation when Braddock’s expedition met with disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela. About ten miles east of what is now Pittsburgh, Braddock’s men were attacked by an alliance of French and Indian warriors. The British column fell into confusion as the Indian warriors formed a half moon around it. Braddock had multiple horses shot out from under him and ultimately was wounded through the lung himself. Two out of three British soldiers were wounded or killed during the four-hour battle.

Washington had multiple bullet holes through his clothes, but by all accounts, behaved with extraordinary poise under fire and tried to rally the remaining troops after Braddock was wounded. When Braddock died a few days later, Washington took his sash and kept it at Mount Vernon as a memento.

Washington’s heroism at the Monongahela eclipsed his earlier failures. Indeed, the military experience that he gained during the French and Indian War—along with his integrity—were the reasons the Continental Congress selected him as commander in chief of the Continental Army in 1775.

By that time, memory of Washington’s culpability in the Jumonville affair had waned significantly. The British had emerged victorious from the French and Indian War, or the Seven Years’ War as it was known in a global context: When the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France surrendered all of its North American territories east of the Mississippi.

But the peace between France and Britain didn’t last long. In 1778, the French signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States, which pitted them against Britain in the American War for Independence. Ironically, this meant the French were now supporting their old foe, George Washington—apparently willing to overlook the fact that he had once unintentionally confessed to the assassination of Ensign Jumonville.

What became of the Ohio Iroquois? Their alliance with the British brought them few rewards, as British settlers expanded onto their Ohio lands in the 1760s. The Revolutionary War dislocated them even farther. Some Ohio Iroquois descendants today are part of the Seneca-Cayuga Nation in Oklahoma.

Tanaghrisson never lived to see any of this. After the Jumonville affair, he and his people relocated to a plantation in central Pennsylvania. While waiting there in exile, Tanaghrisson caught pneumonia and died in early October 1754—a fictional viceroy over an Ohio kingdom that existed only in the British imperial imagination.

Braddock's Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution

Braddock's Defeat was the defining generational experience for many British and American officers, including Thomas Gage, Horatio Gates, and, perhaps most significantly, George Washington. A rich battle history driven by a gripping narrative and an abundance of new evidence, Braddock's Defeat presents the fullest account yet of this defining moment in early American history.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/e0/3fe0356a-4f89-4a0c-8492-8a914109b33d/oct2019_c02_chiefwarriorcrop.jpg)