Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed

The Transcontinental Railroad connected East and West—and accelerated the destruction of what had been in the center of North America

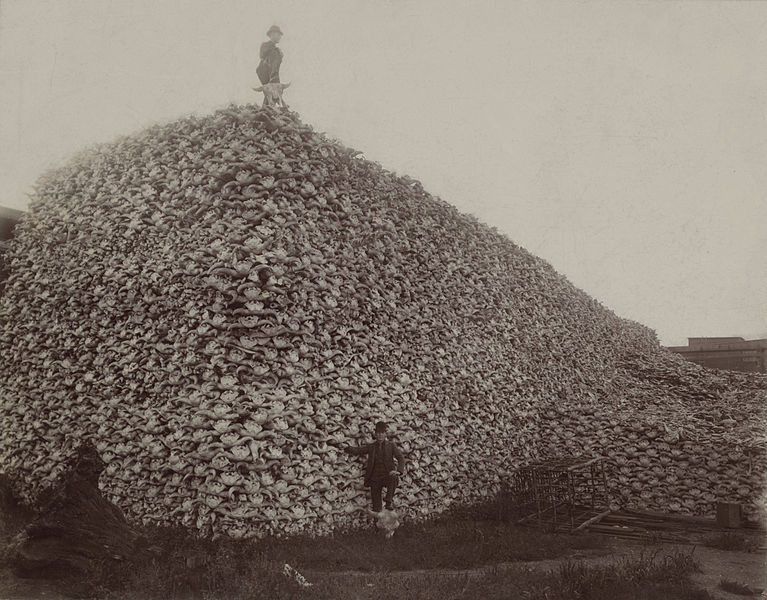

A pile of American bison skulls in the mid-1870s. Photo: Wikipedia

The telegram arrived in New York from Promontory Summit, Utah, at 3:05 p.m. on May 10, 1869, announcing one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the century:

The last rail is laid; the last spike driven; the Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1086 miles west of the Missouri river and 690 miles east of Sacramento City.

The telegram was signed, “Leland Stanford, Central Pacific Railroad. T. P. Durant, Sidney Dillon, John Duff, Union Pacific Railroad,” and trumpeted news of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. After more than six years of backbreaking labor, east officially met west with the driving of a ceremonial golden spike. In City Hall Park in Manhattan, the announcement was greeted with the firing of 100 guns. Bells were rung across the country, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. Business was suspended in Chicago as people rushed to the streets, celebrating to the sounding of steam whistles and cannons booming.

Back in Utah, railroad officials and politicians posed for pictures aboard locomotives, shaking hands and breaking bottles of champagne on the engines as Chinese laborers from the West and Irish, German and Italian laborers from the East were budged from view.

Not long after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, railroad financier George Francis Train proclaimed, “The great Pacific Railway is commenced.… Immigration will soon pour into these valleys. Ten millions of emigrants will settle in this golden land in twenty years.… This is the grandest enterprise under God!” Yet while Train may have envisioned all the glory and the possibilities of linking the East and the West coasts by “a strong band of iron,” he could not imagine the full and tragic impact of the Transcontinental Railroad, nor the speed at which it changed the shape of the American West. For in its wake, the lives of countless Native Americans were destroyed, and tens of millions of buffalo, which had roamed freely upon the Great Plains since the last ice age 10,000 years ago, were nearly driven to extinction in a massive slaughter made possible by the railroad.

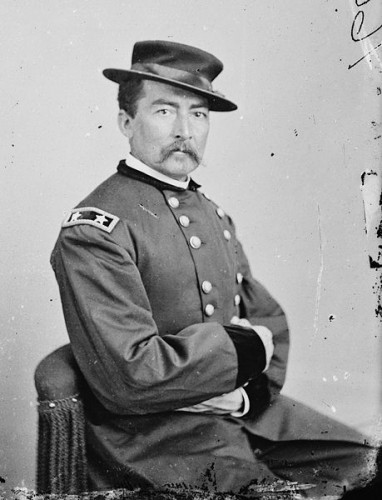

Following the Civil War, after deadly European diseases and hundreds of wars with the white man had already wiped out untold numbers of Native Americans, the U.S. government had ratified nearly 400 treaties with the Plains Indians. But as the Gold Rush, the pressures of Manifest Destiny, and land grants for railroad construction led to greater expansion in the West, the majority of these treaties were broken. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s first postwar command (Military Division of the Mississippi) covered the territory west of the Mississippi and east of the Rocky Mountains, and his top priority was to protect the construction of the railroads. In 1867, he wrote to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, “we are not going to let thieving, ragged Indians check and stop the progress” of the railroads. Outraged by the Battle of the Hundred Slain, where Lakota and Cheyenne warriors ambushed a troop of the U.S. Cavalry in Wyoming, scalping and mutilating the bodies of all 81 soldiers and officers, Sherman told Grant the year before, “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children.” When Grant assumed the presidency in 1869, he appointed Sherman Commanding General of the Army, and Sherman was responsible for U.S. engagement in the Indian Wars. On the ground in the West, Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan, assuming Sherman’s command, took to his task much as he had done in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, when he ordered the “scorched earth” tactics that presaged Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Early on, Sheridan bemoaned a lack of troops: “No other nation in the world would have attempted reduction of these wild tribes and occupation of their country with less than 60,000 to 70,000 men, while the whole force employed and scattered over the enormous region…never numbered more than 14,000 men. The consequence was that every engagement was a forlorn hope.”

The Army’s troops were well equipped for fighting against conventional enemies, but the guerrilla tactics of the Plains tribes confounded them at every turn. As the railways expanded, they allowed the rapid transport of troops and supplies to areas where battles were being waged. Sheridan was soon able to mount the kind of offensive he desired. In the Winter Campaign of 1868-69 against Cheyenne encampments, Sheridan set about destroying the Indians’ food, shelter and livestock with overwhelming force, leaving women and children at the mercy of the Army and Indian warriors little choice but to surrender or risk starvation. In one such surprise raid at dawn during a November snowstorm in Indian Territory, Sheridan ordered the nearly 700 men of the Seventh Cavalry, commanded by George Armstrong Custer, to “destroy villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and to bring back all women and children.” Custer’s men charged into a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, cutting down the Indians as they fled from lodges. Women and children were taken as hostages as part of Custer’s strategy to use them as human shields, but Cavalry scouts reported seeing women and children pursued and killed “without mercy” in what became known as the Washita Massacre. Custer later reported more than 100 Indian deaths, including that of Chief Black Kettle and his wife, Medicine Woman Later, shot in the back as they attempted to ride away on a pony. Cheyenne estimates of Indian deaths in the raid were about half of Custer’s total, and the Cheyenne did manage to kill 21 Cavalry troops while defending the attack. “If a village is attacked and women and children killed,” Sheridan once remarked, “the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack.”

The Transcontinental Railroad made Sheridan’s strategy of “total war” much more effective. In the mid-19th century, it was estimated that 30 milion to 60 million buffalo roamed the plains. In massive and majestic herds, they rumbled by the hundreds of thousands, creating the sound that earned them the nickname “Thunder of the Plains.” The bison’s lifespan of 25 years, rapid reproduction and resiliency in their environment enabled the species to flourish, as Native Americans were careful not to overhunt, and even men like William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was hired by the Kansas Pacific Railroad to hunt the bison to feed thousands of rail laborers for years, could not make much of a dent in the buffalo population. In mid-century, trappers who had depleted the beaver populations of the Midwest began trading in buffalo robes and tongues; an estimated 200,000 buffalo were killed annually. Then the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad accelerated the decimation of the species.

Massive hunting parties began to arrive in the West by train, with thousands of men packing .50 caliber rifles, and leaving a trail of buffalo carnage in their wake. Unlike the Native Americans or Buffalo Bill, who killed for food, clothing and shelter, the hunters from the East killed mostly for sport. Native Americans looked on with horror as landscapes and prairies were littered with rotting buffalo carcasses. The railroads began to advertise excursions for “hunting by rail,” where trains encountered massive herds alongside or crossing the tracks. Hundreds of men aboard the trains climbed to the roofs and took aim, or fired from their windows, leaving countless 1,500-pound animals where they died.

Harper’s Weekly described these hunting excursions:

Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; and a most interesting and exciting scene is the result. The train is “slowed” to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

Hunters began killing buffalo by the hundreds of thousands in the winter months. One hunter, Orlando Brown brought down nearly 6,000 buffalo by himself and lost hearing in one ear from the constant firing of his .50 caliber rifle. The Texas legislature, sensing the buffalo were in danger of being wiped out, proposed a bill to protect the species. General Sheridan opposed it, stating, ”These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

The devastation of the buffalo population signaled the end of the Indian Wars, and Native Americans were pushed into reservations. In 1869, the Comanche chief Tosawi was reported to have told Sheridan, “Me Tosawi. Me good Indian,” and Sheridan allegedly replied, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” The phrase was later misquoted, with Sheridan supposedly stating, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Sheridan denied he had ever said such a thing.

By the end of the 19th century, only 300 buffalo were left in the wild. Congress finally took action, outlawing the killing of any birds or animals in Yellowstone National Park, where the only surviving buffalo herd could be protected. Conservationists established more wildlife preserves, and the species slowly rebounded. Today, there are more than 200,000 bison in North America.

Sheridan acknowledged the role of the railroad in changing the face of the American West, and in his Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army in 1878, he acknowledged that the Native Americans were scuttled to reservations with no compensation beyond the promise of religious instruction and basic supplies of food and clothing—promises, he wrote, which were never fulfilled.

“We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this they made war. Could any one expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

Sources

Books: Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army to the Secretary of War, The Year 1878, Washington Government Printing Office, 1878. Robert G. Angevine, The Railroad and the State: War, Politics and Technology in Nineteenth-Century America, Stanford University Press 2004. John D. McDermott, A Guide to the Indian Wars of the West, University of Nebraska Press, 1998. Ballard C. Campbell, Disasters, Accidents, and Crises in American History: A Reference Guide to the Nation’s Most Catastrophic Events, Facts on File, Inc., 2008. Bobby Bridger, Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West, University of Texas Press, 2002. Paul Andrew Hutton, Phil Sheridan & His Army, University of Nebraska Press 1985. A People and a Nation: A History of the United States Since 1865, Vol. 2, Wadsworth, 2010.

Articles: “Transcontinental Railroad,” American Experience, PBS.org, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/introduction/tcrr-intro/ ”Buffalo Hunting: Shooting Buffalo From the Trains of the Kansas Pacific Railroad,” Harper’s Weekly, December 14, 1867. : “Black Kettle,” New Perspectives on the West, PBS: The West, http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/a_c/blackkettle.htm ”Old West Legends: Buffalo Hunters,” Legends of America, http://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-buffalohunters.html “Completion of the Pacific Railroad,” Hartford Courant, May 11, 1869.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)