On January 20, 1989, my father-in-law, George H.W. Bush, was inaugurated as the 41st president of the United States. My 7-year-old twin daughters got cold during the parade, so they went back to their grandparents’ new home at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The staff members were still wildly moving the Reagans out and the Bushes in—they have about six hours to make that switch from one president to the next. By the time the new residents arrive in the evening, their clothes are hanging in the closet, their pictures are on the walls, and everything they’ve brought with them has found a place in their new home.

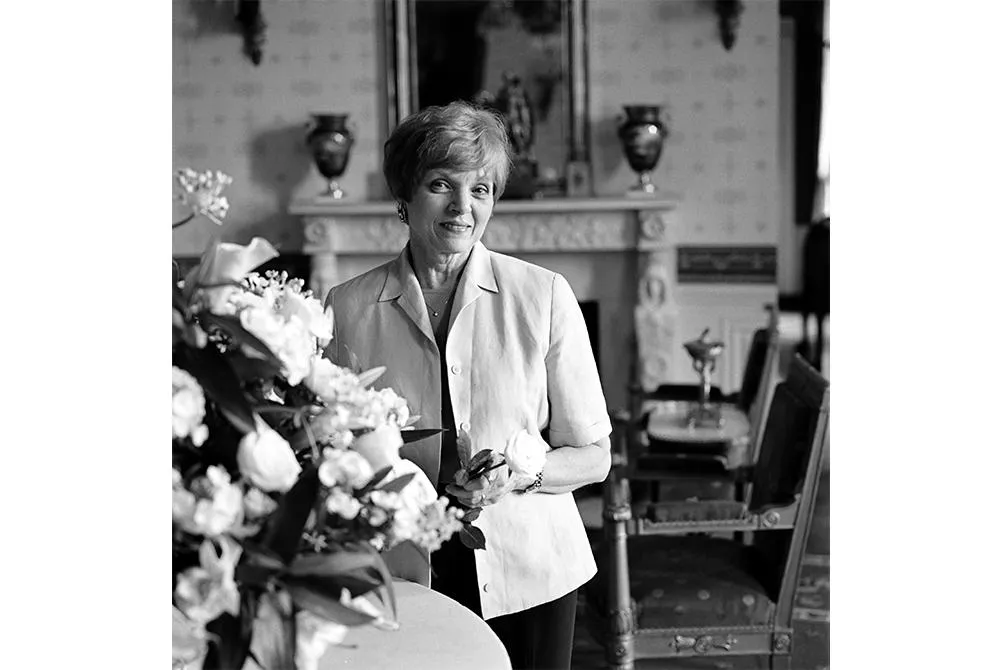

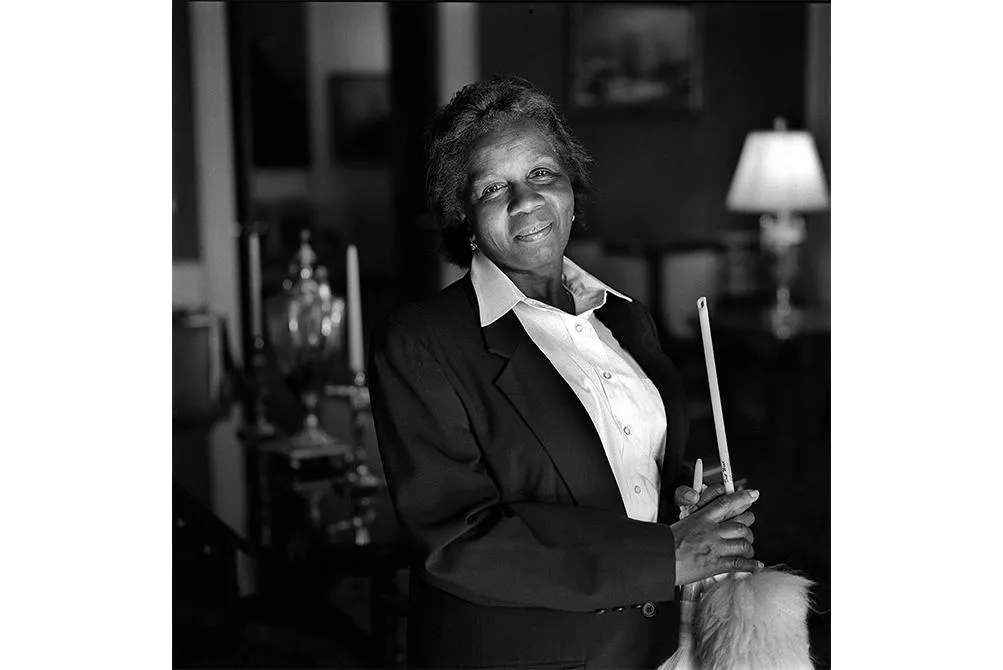

When little Barbara and Jenna showed up that day, the place was still a whirlwind, so Nancy Clark, the White House florist, met them at the door and took them down to the floral shop in the basement. She helped them each make a bouquet for their grandparents’ new bedside tables. Nineteen years later, Nancy was the florist for Jenna’s wedding.

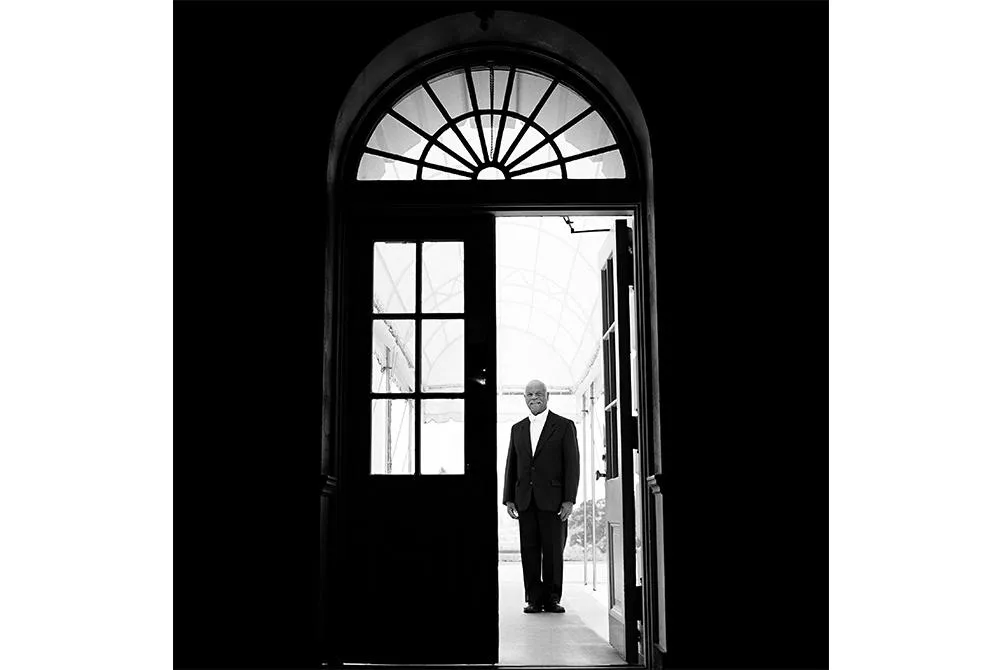

Many people don’t realize that members of the White House staff often stay for decades. The doorman who greeted us each morning, Wilson Roosevelt Jerman, served 11 presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower to Barack Obama. He died of Covid-19 this past May. All the other men and women shown in this article, who were photographed during my husband’s presidency, are still working at the White House.

The people on staff will do just about anything to make you comfortable. That’s their job. George was shocked at first when two men, Sam Sutton and Fidel Medina, introduced themselves to him as his personal valets. George insisted he didn’t need help getting dressed and undressed. His father smiled and said, “You’ll get used to it.”

We were always careful not to take advantage of the staff’s dedication. Barbara and Jenna learned that early on, when their grandfather had just become president. They were playing in the bowling alley and decided to pick up the phone to order food. You can imagine what Barbara Bush thought about two 7-year-old girls doing this! She rushed down to the bowling alley and told them, “This is not a hotel! This is a home. And you’ll never do that again.”

I didn’t need to do much to manage the staff. The usher’s office did that, and they were all so good at what they did. The chefs came up with our daily menus and they knew what we liked. I chose Cris Comerford to be our head chef—she’s still there. She can certainly cook incredibly fancy meals, but you don’t want to have filet mignon every day. Sometimes you just want a hamburger—or if you’re George, a hot dog.

I got more involved when it came to official events. Before we had a state dinner, I helped the florists choose appropriate colors for each country. You didn’t want the centerpieces to have the colors of the guest’s enemy’s flag. We also tried to include a nod to the country on the menu. In the days leading up to the event, the staff would fix one of the items for our family supper and say, “This is what we’re thinking of serving at the dinner.” That was a lot of fun.

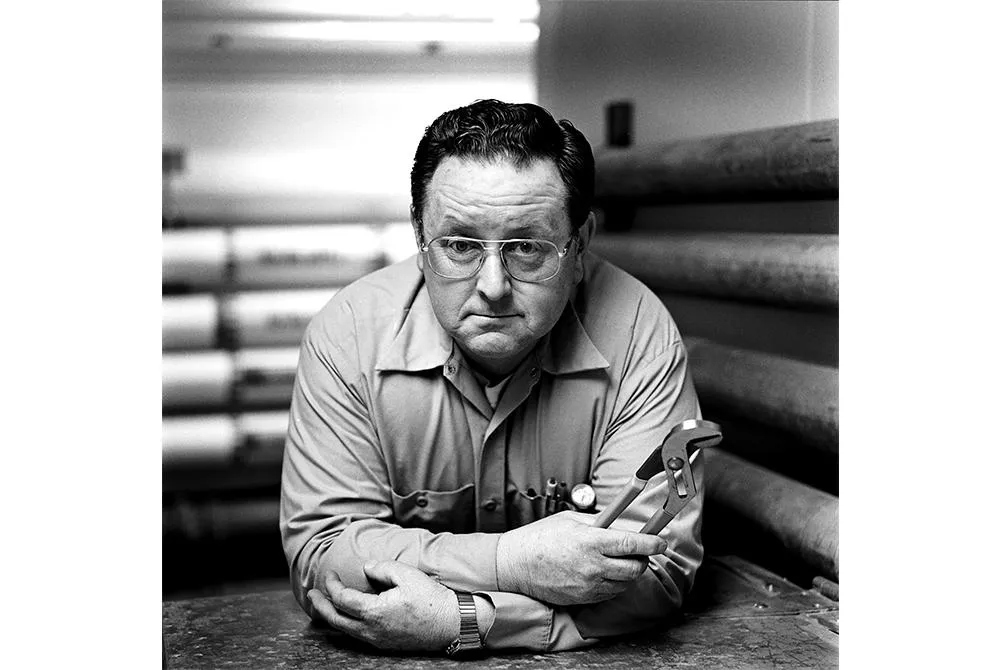

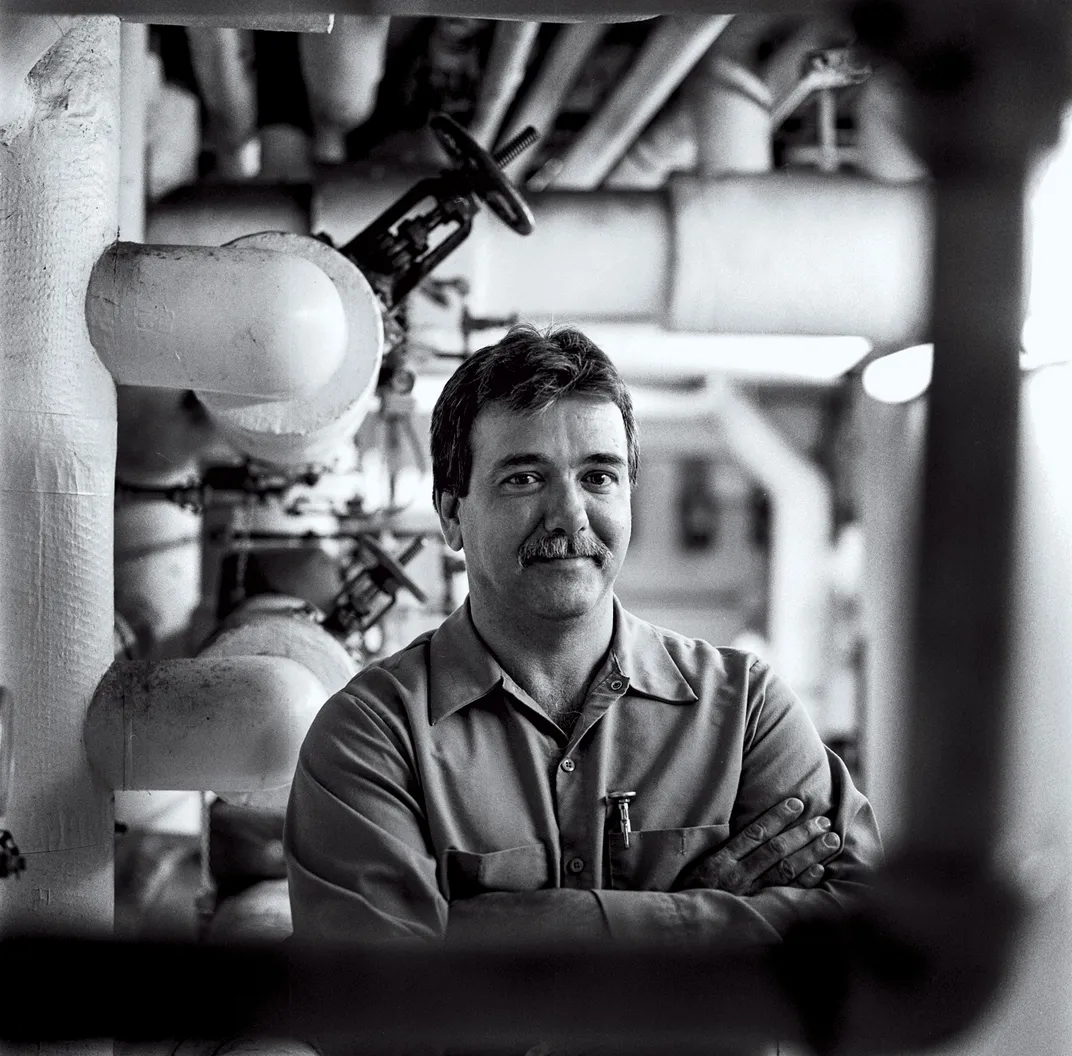

Christmas was another major undertaking. Our first year, 2001, I chose the theme “Home for the Holidays.” Roland Mesnier, our pastry chef, made a replica of the original White House as it looked before British troops set it on fire in 1814. Our carpenters, plumbers and electricians used original floor plans to build 18 scale models of presidents’ homes, from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello to Lyndon B. Johnson’s ranch.

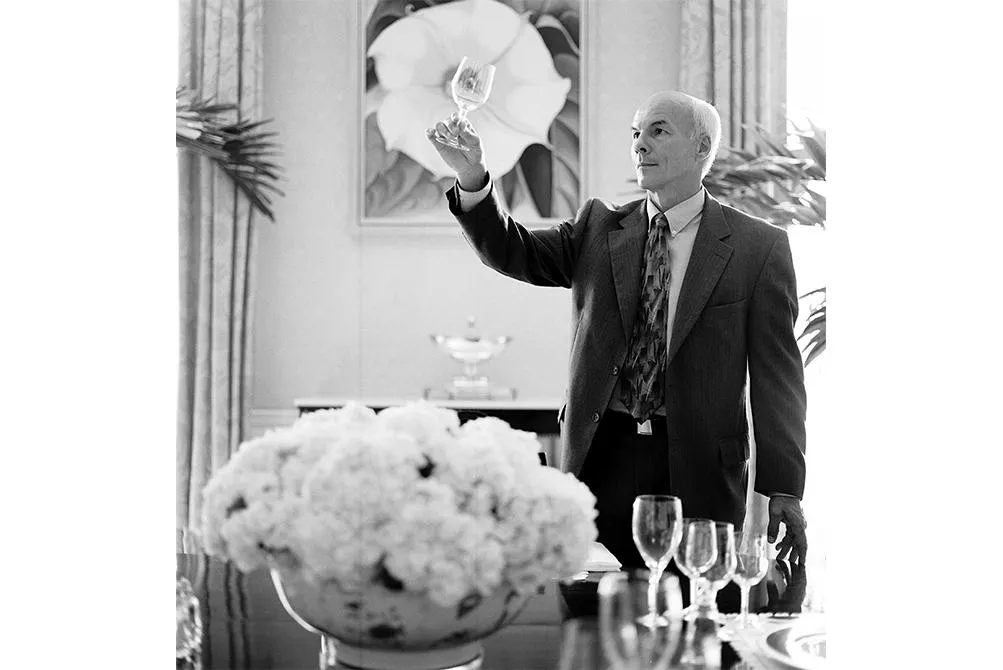

Over the years, the staff became like our friends and family. As Barbara Bush used to say, you could be changing your clothes and a staff member could accidentally open the door to vacuum. They see you in a really intimate way. It was the chief usher, Gary Walters, who saw how unhappy my mother-in-law was with her official portrait and suggested she have a new one painted. She took his advice and we unveiled her new portrait in January 2005, two weeks before George began his second term.

We rarely heard stories about previous presidential families. The chief usher is especially strict about making sure that no one discusses any family’s private life. That makes the current family feel secure. You know that if your children act out and you fuss at them, no one’s going to tell.

But even though the staff doesn’t talk about them, you’re aware of all the other families who have lived in the White House before you. The furniture in the Lincoln bedroom was really the Lincolns’ furniture. Every day, I walked past the black lacquer screen Nancy Reagan added to the upstairs hallway. The walls of our dining room were covered with the light, cheerful fabric the Clintons had chosen. And our staff members had served other presidents before us.

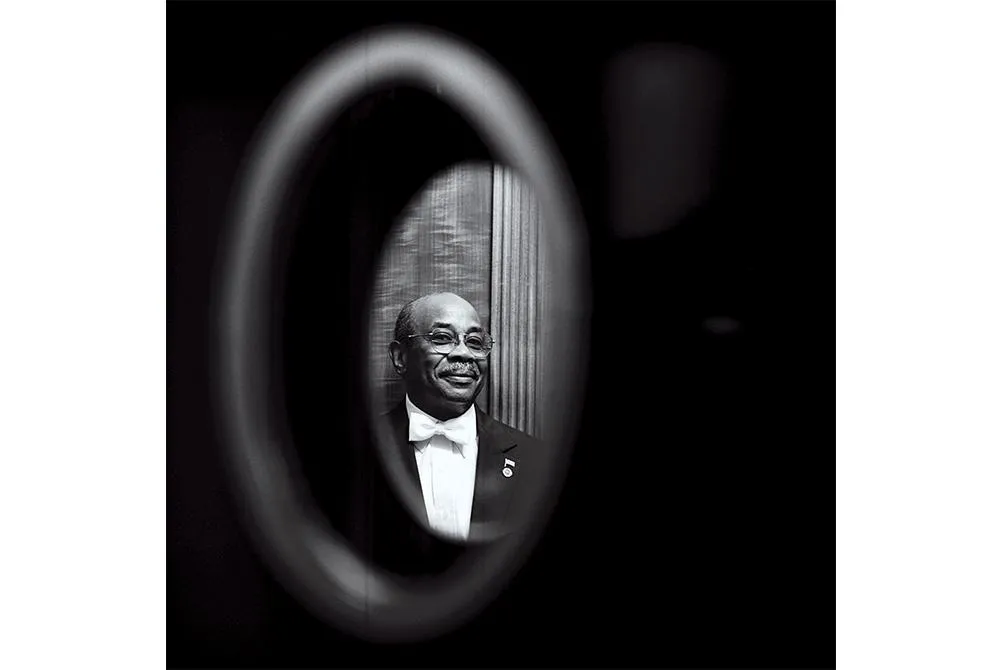

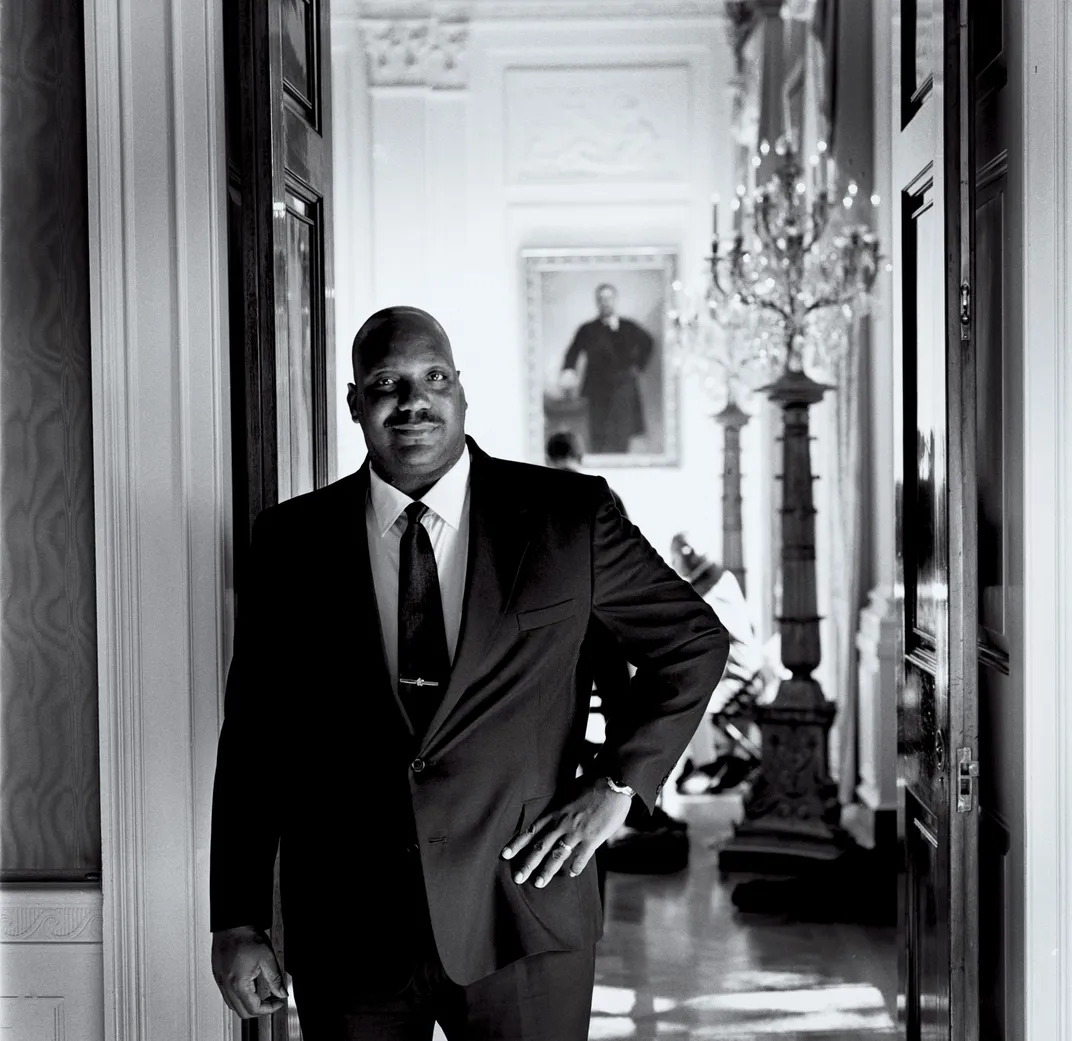

When Barbara Bush died in 2018, Melania Trump brought Buddy Carter, a White House butler, and George Hainey, a former maître d’, down to Houston for the funeral. My father-in-law was so glad to see them, and what made it even more special was that three other former presidents who were there—President Obama, President Clinton and my husband—knew those men well. All of our families hugged them.

There’s great continuity in that, and it’s part of a larger continuity that’s made our country as stable as it is. There are so many government workers who serve from president to president. I see that as the big ballast of the ship of state.

The same sense of continuity carries through inside the White House, in very personal ways. When we gave the Obamas their tour, my daughters remembered visiting their grandfather as little girls and they showed Sasha and Malia how to slide down the ramp that comes down from the solarium in the private quarters.

It must be jarring for the staffers when a new president moves in, but you’d never know it. They welcome the new family, and don’t miss a beat when a president comes home on Inauguration Day, whether it’s for the first or second time. That’s what they’re there for—to serve the president of the United States—and they’re very serious about it. They know they’re the stewards of the presidency itself.

Editor's note: This story went to press before the recent Covid-19 outbreak at the White House.

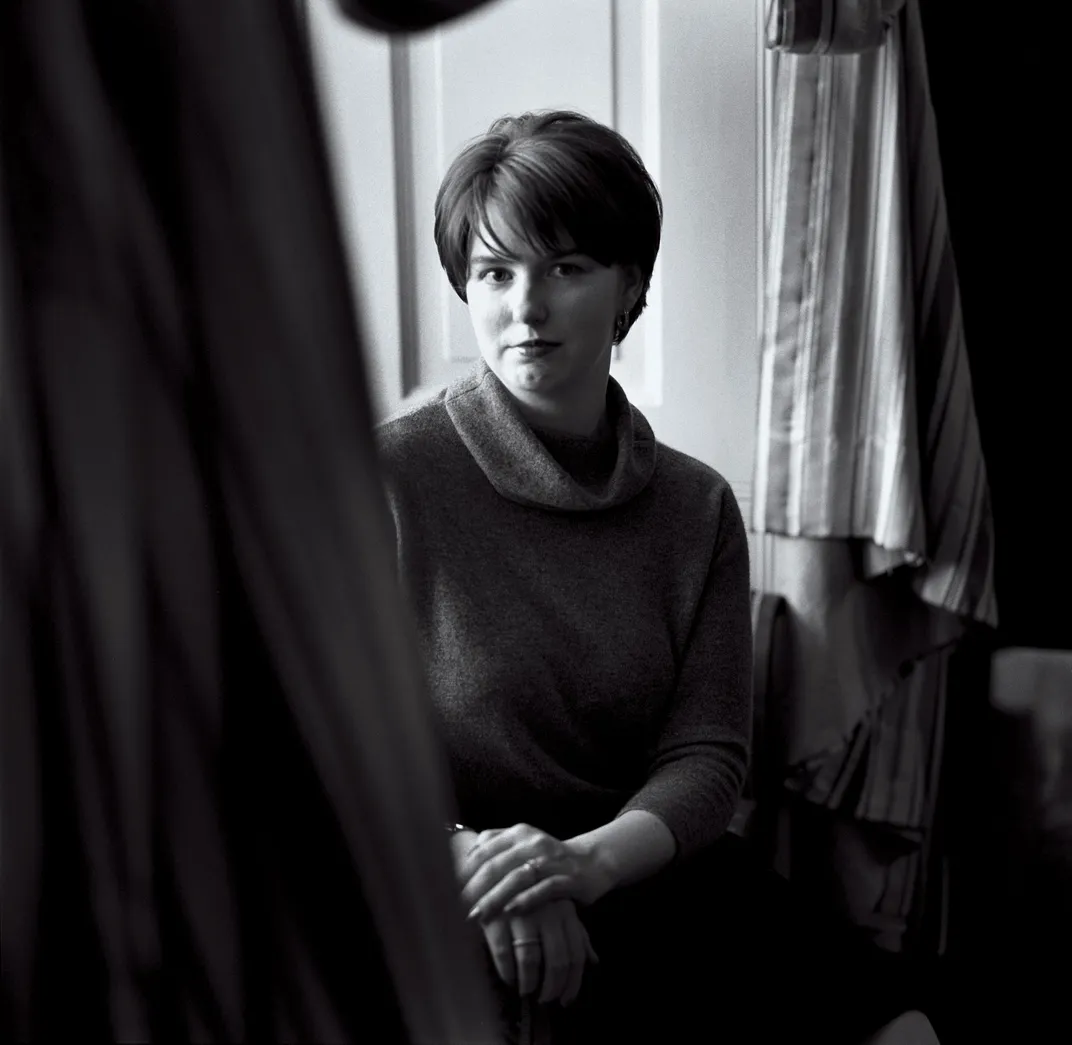

An earlier version of this story misidentified the photo of Nancy Clarke as Nancy F. Mitchell. Smithsonian regrets the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/0d/9c0dfbf7-dd6c-4f5f-83aa-0197c09484c1/mobile.jpg)

:focal(961x180:962x181)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/c9/a1c9974f-360a-41d5-9422-3383d9cae552/white-house-opener-replacement.jpg)