Who Were Cleopatra’s Rivals for Mark Antony’s Love?

The Roman general’s third and fourth wives, Fulvia and Octavia, adopted varying strategies for luring their husband away from the queen of Egypt

Cleopatra VII, queen of Egypt, remains one of the most notorious women of the ancient world. Her relationships with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony were a source of particular scandal, not least in Rome. The statesman Cicero, for one, summed up his feelings about her with a simple “I hate the queen.” But far less talked about today are the women who arguably had the most reason to despise her. Fulvia and Octavia, the Roman-born wives of Antony, became Cleopatra’s staunchest love rivals. Their stories—replete with episodes of revenge, bloodshed and genital-centered missiles—deserve to be much better known.

Fulvia was married to Antony when the Roman general and politician embarked upon his affair with Cleopatra. Hailing from a wealthy family in central-western Italy, she had been twice married and twice widowed before her relationship with Antony began. A cousin of the late Caesar, Antony held an impressive military record. Fulvia played a part in the forging of her husband’s alliance with Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew and heir (later known as Augustus), and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, another of Caesar’s allies. The so-called Second Triumvirate, which empowered the three men to rule the empire between them, was fortified by the engagement of Fulvia’s daughter from her first marriage, Claudia, to Octavian.

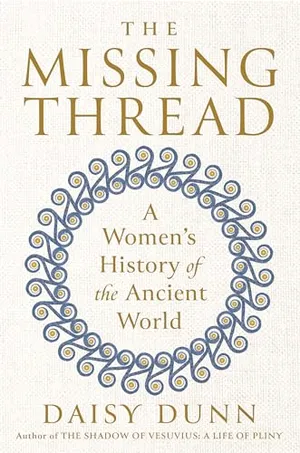

The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World

A dazzlingly ambitious history of the ancient world that places women at the center—from Cleopatra to Boudica, Sappho to Fulvia, and countless other artists, writers, leaders and creators of history

Fulvia suffered as a consequence of Antony’s longstanding enmity with Cicero. The orator repeatedly reproached the triumvirs for the threat they posed to the republican system. In his Philippics, a series of vitriolic speeches lambasting Antony, Cicero cast Fulvia as a bloodthirsty and rapacious villainess. Fulvia was said to have taken revenge after Cicero was killed by Antony’ soldiers in 43 B.C.E. She allegedly picked up his decapitated head, spat on it and punctured his tongue with her hairpins.

It was two years later that the tussle between Fulvia and Cleopatra began in earnest. In the aftermath of the Battle of Philippi, Antony had reconvened with the queen of Egypt, whom he’d previously met when she was a teenager. The civil war had seen him claim victory with Octavian over the Liberators who had assassinated Caesar in 44 B.C.E. Ancient historians made much of the attraction between victor and queen. Antony “was struck by her appearance and intelligence,” wrote the historian Appian, “and at once conquered by her, as if he were a youth, though in fact he was 40 years old.” Cleopatra knew that a relationship with Antony could be mutually beneficial. She required support from Rome. He required funds and support for a war that was brewing against the Parthians (of modern Iran).

As news of a serious relationship between Antony and Cleopatra spread to Rome, people naturally assumed that Fulvia would do anything in her power to bring him home. So it was that, when Fulvia stirred up a war in Italy in 41 B.C.E., she was believed to have acted simply out of jealousy and vindictive cunning.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d0/68/d068b024-2030-4404-9b2a-c3cb17c37900/fulvia_y_marco_antonio_o_la_venganza_de_fulvia_museo_del_prado.jpg)

Fulvia’s motivations were in fact more complex. The Perusine War saw her join forces with her brother-in-law Lucius in an effort to redress the balance of power in the triumvirate by championing Antony over Octavian. Fulvia had been personally offended by Octavian’s decision to divorce her daughter so he could marry another woman. The tension between former mother- and son-in-law grew so intense that Octavian claimed that Fulvia threatened him. “Either go to bed with me,” she supposedly said, “or fight me.” They chose to fight.

The war led to one of the bloodiest sieges in ancient history. Although power ostensibly lay with Lucius, a senior senator, the real power, according to Roman historian Cassius Dio, lay with Fulvia. She not only helped Lucius in raising legions, but also traveled to Praeneste (now Palestrina in central Italy), where “a sword was girded to her side and she gave signals to the soldiers and often even addressed them.”

Fulvia and Lucius sought refuge inside the city walls as Octavian’s forces began to hurl missiles. Several of the lead sling bullets the men discharged were inscribed with crude messages. “I’m aiming for Fulvia’s clitoris,” reads one, which has miraculously been recovered from the site. Octavian’s forces gained the upper hand and starved the citizens within the walls into submission. Fulvia and Lucius were spared.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/8b/618b6d2a-6e01-4f26-b0f4-063cf7e998b6/fulvia_antonia.jpg)

Antony made no hurry to return to Rome in the wake of the disaster. Cleopatra had become pregnant with his child, or rather, his children. In 40 B.C.E., she gave birth to twins, Cleopatra Selene, named after the moon, and Alexander Helios, named after the sun. A third child, Ptolemy Philadelphus, would follow. Antony had barely had time to get to know the children he had by Fulvia in Rome. Soon, Fulvia made the decision to travel to him with their two young boys.

But there was little time for a family reunion. Antony blamed Fulvia for the chaos of the Perusine War and blithely left her behind in Greece, where she had become sick, when he was summoned to a conference with Octavian in Italy. News reached him there that Fulvia had died of her illness.

“The death of this public affairs-obsessed woman who fanned the flames of war out of jealousy for Cleopatra,” wrote Appian, “seemed extremely profitable for both parties, who were freed of her.” The consensus remained that Fulvia had whipped up civil war in response to her husband’s affair with Cleopatra alone. Her efforts to help Antony were never recognized.

If Cleopatra believed she now had Antony to herself, she was wrong. As part of the renewal of his political alliance with Octavian, Antony agreed to marry the future emperor’s sister, Octavia. Cleopatra now had a new rival. Beautiful, level-headed and a recently widowed mother of three, Octavia was, by popular repute, “a most wonderful thing.” Antony was enthusiastic for the match yet made no effort to conceal from her his ongoing relationship with Cleopatra.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f0/e3/f0e379f6-6659-484c-bd27-3a67a2639d8b/angelica_kauffmann_-_virgil_reading_the_aeneid_to_augustus_and_octavia_hermitage.jpg)

Octavia and Antony soon had two daughters, Antonia the Elder and Antonia the Younger. Their relationship was strained, however, by Antony’s frequent absences and growing tensions with Octavian.

“If the worst should prevail and war occur,” Octavia told her brother, presciently, “it is the fate of one of you to conquer and the other to be conquered—it is unclear which way this will go—but in either case, my life will be misery.” According to Antony’s biographer Plutarch, Octavia foresaw that she was destined to become either the wife of the man who had killed her brother or the sister of the man who had killed her husband. She eventually took the initiative of sailing to Antony in a foreboding echo of Fulvia’s actions. Octavian was happy for his sister to go: If Antony was anything less than respectful toward her, he would have grounds for declaring war.

Octavia arrived in the east to a pile of letters from her errant husband. Antony asked that she proceed no further while he was on expedition. Frustrated but not deceived into believing that the Parthian War alone was keeping him, Octavia sent Antony a simple message. Where was she to send the luggage and presents she had brought for the soldiers? Her kindness was characteristic and delighted Antony, but Cleopatra viewed it as a ruse to entice him away. Fearful that Antony would abandon her in favor of his wife, Cleopatra stopped eating and came before him looking gaunt whenever he said that he had to leave. At one point, Antony was so afraid Cleopatra might kill herself that he put off a military campaign.

Plutarch believed that Cleopatra was indebted to Fulvia for teaching Antony to be obedient to domineering women. This may have been unfair, but the people of Rome felt increasingly sympathetic toward Octavia, especially after Antony instructed her to leave their home. Maintaining her dignity, Octavia agreed to do so, and she continued to care for not only the children she had by Antony, but Antony’s children by Fulvia, too. In 32 B.C.E., Antony filed for divorce from Octavia. He was now free to marry Cleopatra.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/02/e7/02e7021e-61f3-4078-be95-fef398c5801c/2560px-proculeius_weerhoudt_cleopatra_ervan_zich_te_doorsteken_rijksmuseum_sk-a-641.jpeg)

Octavia was determined that her brother not use her as an excuse to declare war on Antony, “since it was no fine thing to hear that, of the most powerful rulers, one plunged the Romans into civil war out of love for a woman, the other out of resentment on a woman’s behalf,” as Plutarch later wrote. But Octavian couldn’t help himself. The opportunity to triumph over his political partner had finally come.

Octavian had Antony’s will read aloud. Not only had Antony requested to be buried with Cleopatra when he died, the will purportedly said, but he had also appointed their children his heirs. The Roman Senate, fearing Egypt’s dominance over Rome, stripped Antony of his political powers. As a vote was passed to declare war on Cleopatra—and Cleopatra alone—Octavia’s worst fears were fulfilled.

The decisive battle was fought between Antony and Cleopatra on one side, Octavian on the other, on the waters off Actium in northwest Greece in 31 B.C.E. Cleopatra, commanding her own reserve armada, led an important breakthrough. But Octavian’s forces carried the day. Some ancient writers and poets, such as Horace, implied that the queen purposely led Antony to defeat in order to gain ownership of him as a partner. This is implausible, but she did ensure that she had a plan by which they might together elude servitude at the hands of Octavian.

The couple’s dual suicide rightly became one of the most famous passages in history. What is less remembered, though, is that in her final days, Cleopatra pleaded with Octavian for leniency by offering to send his wife and sister presents. Octavia may have been her love rival, but Cleopatra recognized her power and influence. Octavia became the last member of the love triangle standing. Ever magnanimous, she agreed to raise the surviving children of both Cleopatra and Fulvia together with her own. Love conquered rivalry.

Adapted from The Missing Thread: A Women’s History of the Ancient World by Daisy Dunn, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Daisy Dunn.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daisy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daisy.png)