Why Are Jim Thorpe’s Olympic Records Still Not Recognized?

In 1912, Jim Thorpe became the greatest American Olympian of all time, but not if you ask the IOC

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jim-Thorpe-Stockholm-631.jpg)

It’s been 100 years since Jim Thorpe dashed through the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, and we’re still chasing him. Greatest-evers are always hard to quantify, but Thorpe is especially so, a laconic, evasive passerby who defies Olympic idealizing. A breakfast of champions for Thorpe was no bowl of cereal. It was fried squirrel with creamed gravy after running all night in the woods at the heels of his dogs. Try catching up with that.

He was a reticent Sac and Fox Indian from the Oklahoma frontier, orphaned as a teenager and raised as a ward of government schools, uncomfortable in the public eye. When King Gustaf V of Sweden placed two gold medals around Thorpe’s neck for winning the Olympic pentathlon and decathlon and pronounced him the greatest athlete in the world, he famously muttered, “Thanks,” and ducked more illustrious social invitations to celebrate at a succession of hotel bars. “I didn’t wish to be gazed upon as a curiosity,” he said.

Thorpe’s epic performance in the 15 events that made up the pentathlon and decathlon at the 1912 Summer Games remains the most solid reflection we have of him. Yet even that has a somewhat shadowy aspect. The International Olympic Committee stripped his medals and struck his marks from the official record after learning that he had violated the rules of amateurism by playing minor-league baseball in 1909-10.

“Those Olympic records are the best proof that he was superb, and they aren’t official,” says Kate Buford, author of a new biography of Thorpe, Native American Son. “He’s like the phantom contender.”

Phantomness has left him open to stigma and errors. For instance, it was popularly believed that Thorpe was careless of his feats, a “lazy Indian” whose gifts were entirely bestowed by nature. But he was nonchalant only about celebrity, which he distrusted. “He was offhand, modest, casual about everything in the way of fame or eminence achieved,” recalled one of his teachers, the poet Marianne Moore.

In fact, Thorpe was a dedicated and highly trained athlete. “I may have had an aversion for work,” he said, “but I also had an aversion for getting beat.” He went to Stockholm with a motive: He wanted to marry his sweetheart, Iva Miller. Her family disapproved of the match, and Thorpe was out to prove that a man could make a good enough living at games to support a wife. Point proved: They would be married in 1913. Photographs of him at the time verify his seriousness of purpose, showing a physique he could only have earned with intense training. He was a ripped 185 pounds with a 42-inch chest, 32-inch waist and 24-inch thighs.

“Nobody was in his class,” says Olympic historian Bill Mallon. “If you look at old pictures of him he looks almost modern. He’s cut. He doesn’t look soft like the other guys did back then. He looks great.”

The physique was partly the product of hard labor in the wilderness of the Oklahoma Territory. By age 6, Thorpe could already shoot, ride, trap and accompany his father, Hiram, a horse breeder and bootlegger who would die of blood poisoning, on 30-mile treks stalking prey. Jim Thorpe was an expert wrangler and breaker of wild horses, which he studied for their beautiful economy of motion and tried to emulate. Clearly the outdoors taught him the famous looseness of movement so often mistaken for lassitude. “He moved like a breeze,” sportswriter Grantland Rice observed.

The discovery of Thorpe at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the government-run boarding institution for Native Americans he attended from 1904 to 1913, between bouts of truancy, is a well-worn story. In 1907 he was ambling across the campus when he saw some upperclassmen practicing the high jump. He was 5-foot-8, and the bar was set at 5-9. Thorpe asked if he could try—and jumped it in overalls and a hickory work shirt. The next morning Carlisle’s polymath of a football and track coach, Glenn “Pop” Warner, summoned Thorpe.

“Have I done anything wrong?” Thorpe asked.

“Son, you’ve only broken the school record in the high jump. That’s all.”

Carlisle, a hybrid trade school and academy, was devoted to the forcible cultural assimilation of American Indian children. Those who knew Thorpe as a schoolboy received the purest impression of him; before he was a champion at his peak, or a guarded celebrity, he was just a head ducker with an uncertain mouth who would have been happy to hunt and handle horses for the rest of his life. He hated the shut-in strictures of school, and he bolted every formal institution he attended.

Carlisle’s piano teacher, Verna Whistler, described Thorpe as guileless. “He had an open face, an honest look, eyes wide apart, a picture of frankness but not brilliance. He would trust anybody.” Moore was an unconventional young Bryn Mawr graduate when she went to work as a teacher at Carlisle. She taught typing, stenography and bookkeeping, basic courses designed to help students conduct their business in the white man’s world. She recalled Thorpe as “liked by all rather than venerated or idolized....[His] modesty, with top performance, was characteristic of him, and no back talk, I never saw him irascible, sour or primed for vengeance.” Moore noted that Thorpe “wrote a fine, even clerical hand—every character legible; every terminal curving up—consistent and generous.” His appearance on the gridiron, she said, was the “epitome of concentration, wary, with an effect of plenty in reserve.”

With students from 6 to college age, at its height Carlisle had an enrollment of no more than 1,000 pupils, yet on the collegiate playing fields it was the equal of the Ivy League powers, one of the more remarkable stories in American sports. This was partly thanks to Thorpe, who won renown in football, baseball, track and lacrosse, and also competed in hockey, handball, tennis, boxing and ballroom dancing. At track meets, Warner signed him up for six and seven events. Once, Thorpe single-handedly won a dual meet against Lafayette, taking first in the high hurdles, low hurdles, high jump, long jump, shot put and discus throw.

The result of all this varied activity was that he became highly practiced in two methods modern athletes now recognize as building blocks of performance: imitation and visualization. Thorpe studied other athletes as closely as he had once studied horses, borrowing their techniques. He was “always watching for a new motion which will benefit him,” Warner said.

Until 1912, Thorpe had never thrown a javelin or pole-vaulted. He was so inexperienced in the javelin that when he competed in the Eastern Olympic Trials in New York’s Celtic Park, he didn’t know he could take a running start. Instead he threw from a standing position with “the awkwardness of a novice,” according to a reporter. Nevertheless, he managed second place.

By the time Thorpe embarked for Stockholm aboard the ocean liner Finland with the rest of the U.S. Olympic contingent—among whom numbered a West Pointer named George Patton and a Hawaiian swimmer named Duke Kahanamoku—he was in the peak shape of his life and spent a good deal of his time tapering and visualizing. This led to the legend that he was merely a skylarker. Newspaperman Francis Albertanti of the New York Evening Mail saw Thorpe relaxing on a deck chair. “What are you doing, Jim, thinking of your Uncle Sitting Bull?” he asked.

“No, I’m practicing the long jump,” Thorpe replied. “I’ve just jumped 23 feet eight inches. I think that will win it.”

It’s a favorite game of sportswriters to argue the abstract question of which athletes from different eras would win in head-to-head competition. The numbers Thorpe posted in Stockholm give us a concrete answer: He would.

Thorpe began the Olympics by crushing the field in the now-defunct pentathlon, which consisted of five events in a single day. He placed first in four of them, dusting his competition in the 1,500-meter run by almost five seconds.

A week later the three-day decathlon competition began in a pouring rain. Thorpe opened the event by splashing down the track in the 100-meter dash in 11.2 seconds—a time not equaled at the Olympics until 1948.

On the second day, Thorpe’s shoes were missing. Warner hastily put together a mismatched pair in time for the high jump, which Thorpe won. Later that afternoon came one of his favorite events, the 110-meter hurdles. Thorpe blistered the track in 15.6 seconds, again quicker than Bob Mathias would run it in ’48.

On the final day of competition, Thorpe placed third and fourth in the events in which he was most inexperienced, the pole vault and javelin. Then came the very last event, the 1,500-meter run. The metric mile was a leg-burning monster that came after nine other events over two days. And he was still in mismatched shoes.

Thorpe left cinders in the faces of his competitors. He ran it in 4 minutes 40.1 seconds. Faster than anyone in 1948. Faster than anyone in 1952. Faster than anyone in 1960—when he would have beaten Rafer Johnson by nine seconds. No Olympic decathlete, in fact, could beat Thorpe’s time until 1972. As Neely Tucker of the Washington Post pointed out, even today’s reigning gold medalist in the decathlon, Bryan Clay, would beat Thorpe by only a second.

Thorpe’s overall winning total of 8,412.95 points (of a possible 10,000) was better than the second-place finisher, Swede Hugo Wieslander, by 688. No one would beat his score for another four Olympics.

Mallon, co-founder of the International Society of Olympic Historians, who has served as a consultant statistician to the IOC, believes that Thorpe’s 1912 performances establish him as “the greatest athlete of all time. Still. To me, it’s not even a question.” Mallon points out that Thorpe was number one in four Olympic events in 1912 and placed in the top ten in two more—a feat no modern athlete has accomplished, not even the sprinter and long-jumper Carl Lewis, who won nine Olympic gold medals between 1984 and 1996. “People just don’t do that,” Mallon says.

The Olympics weren’t the only highlights of 1912 for Thorpe. He returned to lead Carlisle’s football team to a 12-1-1 record, running for 1,869 yards on 191 attempts—more yards in a season than O.J. Simpson would run for USC in 1968. And that total doesn’t include yardage from two games Thorpe played in. It’s possible that, among the things Thorpe did in 1912, he was college football’s first 2,000-yard rusher.

Numbers like those are the ghostly outline of Thorpe’s athleticism; they burn through time and make him vivid. Without them, myth and hyperbole replace genuine awe over his feats, and so does pity at his deterioration from superstar to disgraced hero. The Olympic champion would become a barnstormer—major-league baseball player, co-founder of the National Football League and even pro basketball player—before winding up a stunt performer and Hollywood character actor. In his later life Thorpe struggled to meet financial obligations to his seven children and two ex-wives, especially during the Great Depression. He worked as a security guard, construction worker and ditch digger, among other things. When he contracted lip cancer in 1951 he sought charity treatment from a Philadelphia hospital, which led his opportunistic third wife, Patricia, to claim weepingly at a press conference that they were destitute. “We’re broke. Jim has nothing but his name and his memories. He has spent money on his own people and given it away. He has often been exploited.” Despite Patricia’s claims, however, they weren’t impoverished; Thorpe hustled tirelessly on the lecture circuit, and they lived in a modest but comfortable trailer home in suburban Lomita, California. He died there of heart failure in 1953 at age 64.

The IOC’s decision in 1912 to strip Thorpe’s medals and strike out his records was not just intended to punish him for violating the elitist Victorian codes of amateurism. It was also intended to obscure him—and to a certain extent it succeeded.

Thorpe’s public reserve didn’t help his cause. He refused to campaign for his reputation, or to fight for his Olympic medals. “I won ’em, and I know I won ’em,” he told his daughter Grace Thorpe. On another occasion he said, “I played with the heart of an amateur—for the pure hell of it.”

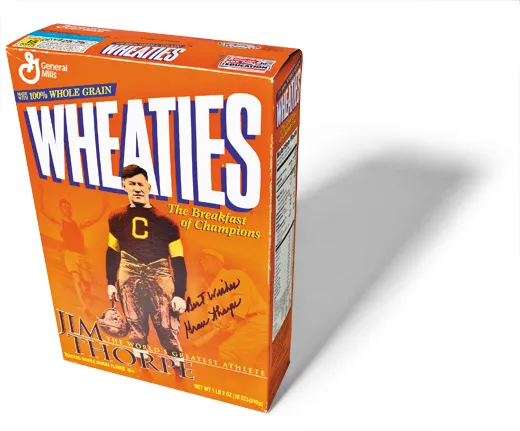

It’s an astonishing fact that the greatest athlete in American history would not appear on a Wheaties box, the ratification of champions, until 2001, and only after a tireless letter-writing campaign.

Here’s another fact: Thorpe’s Olympic victories still have not been properly reinstated in the official record.

It’s commonly believed that Thorpe at last received Olympic justice in October of 1982 when the IOC bowed to years of public pressure and delivered two replica medals to his family, announcing, “The name of James Thorpe will be added to the list of athletes who were crowned Olympic champions at the 1912 Games.” What’s less commonly known is that the IOC appended this small, mean sentence: “However, the official report for these Games will not be modified.”

In other words, the IOC refused even to acknowledge Thorpe’s results in the 15 events he competed in. To this day the Olympic record does not mention them. The IOC also refused to demote Wieslander and the other runners-up from their elevated medal status. Wieslander’s results stand as the official winning tally. Thorpe was merely a co-champion, with no numerical evidence of his overwhelming superiority. This is no small thing. It made Thorpe an asterisk, not a champion. It was lip service, not restitution.

On this 100-year anniversary of the Stockholm Games, there are several good reasons for the IOC to relent and fully recognize Thorpe as the sole champion that he was. Countless white athletes abused the amateurism rules and played minor-league ball with impunity. What’s more, the IOC did not follow its own rules for disqualification: Any objection to Thorpe’s status should have been raised within 30 days of the Games, and it was not. It was nice of the IOC to award replica medals to Thorpe’s family, but those are just souvenirs. After 100 years of phantom contending, Thorpe should enter the record as the incomparable that he was.