Why Footbinding Persisted in China for a Millennium

Despite the pain, millions of Chinese women stood firm in their devotion to the tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/48/ec4893b8-64b8-4e25-b21d-f5cdf8414cd6/main-collage.jpg)

For the past year I have been working with Britain’s BBC television to make a documentary series on the history of women. In the latest round of filming there was an incident that haunts me. It took place during a segment on the social changes that affected Chinese women in the late 13th century.

These changes can be illustrated by the practice of female foot-binding. Some early evidence for it comes from the tomb of Lady Huang Sheng, the wife of an imperial clansman, who died in 1243. Archaeologists discovered tiny, misshapen feet that had been wrapped in gauze and placed inside specially shaped “lotus shoes.” For one of my pieces on camera, I balanced a pair of embroidered doll shoes in the palm of my hand, as I talked about Lady Huang and the origins of foot-binding. When it was over, I turned to the museum curator who had given me the shoes and made some comment about the silliness of using toy shoes. This was when I was informed that I had been holding the real thing. The miniature “doll” shoes had in fact been worn by a human. The shock of discovery was like being doused with a bucket of freezing water.

Foot-binding is said to have been inspired by a tenth-century court dancer named Yao Niang who bound her feet into the shape of a new moon. She entranced Emperor Li Yu by dancing on her toes inside a six-foot golden lotus festooned with ribbons and precious stones. In addition to altering the shape of the foot, the practice also produced a particular sort of gait that relied on the thigh and buttock muscles for support. From the start, foot-binding was imbued with erotic overtones. Gradually, other court ladies—with money, time and a void to fill—took up foot-binding, making it a status symbol among the elite.

A small foot in China, no different from a tiny waist in Victorian England, represented the height of female refinement. For families with marriageable daughters, foot size translated into its own form of currency and a means of achieving upward mobility. The most desirable bride possessed a three-inch foot, known as a “golden lotus.” It was respectable to have four-inch feet—a silver lotus—but feet five inches or longer were dismissed as iron lotuses. The marriage prospects for such a girl were dim indeed.

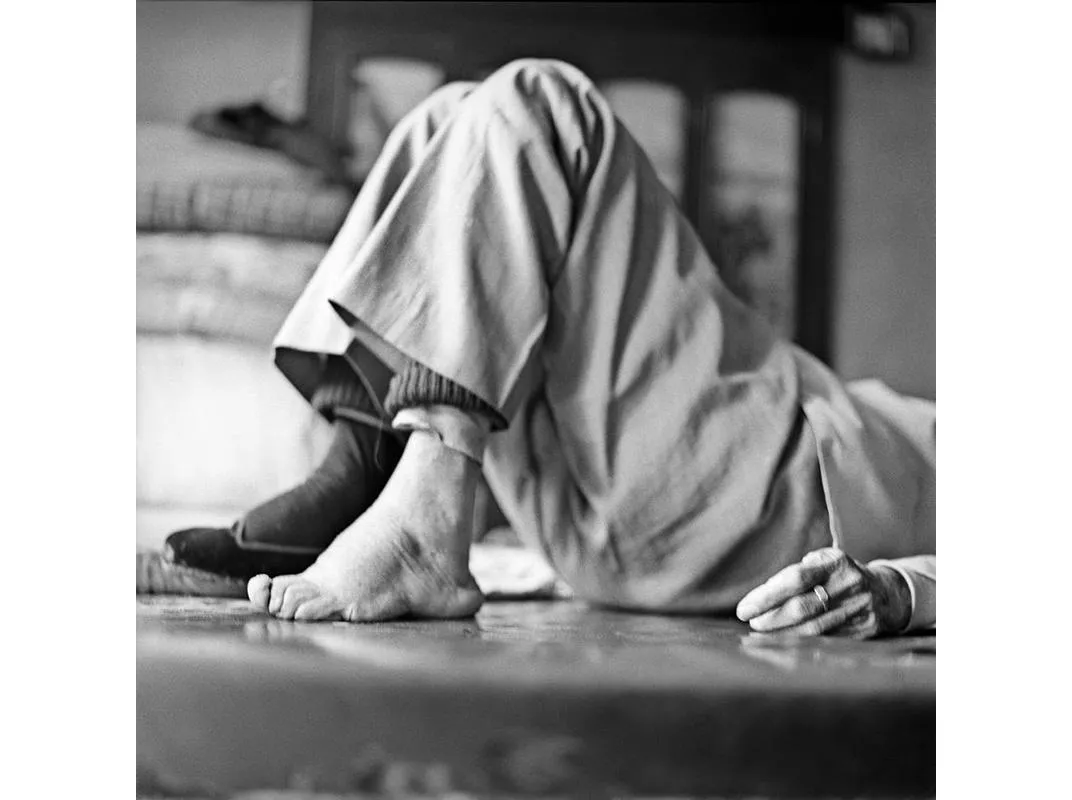

As I held the lotus shoes in my hand, it was horrifying to realize that every aspect of women’s beauty was intimately bound up with pain. Placed side by side, the shoes were the length of my iPhone and less than a half-inch wider. My index finger was bigger than the “toe” of the shoe. It was obvious why the process had to begin in childhood when a girl was 5 or 6.

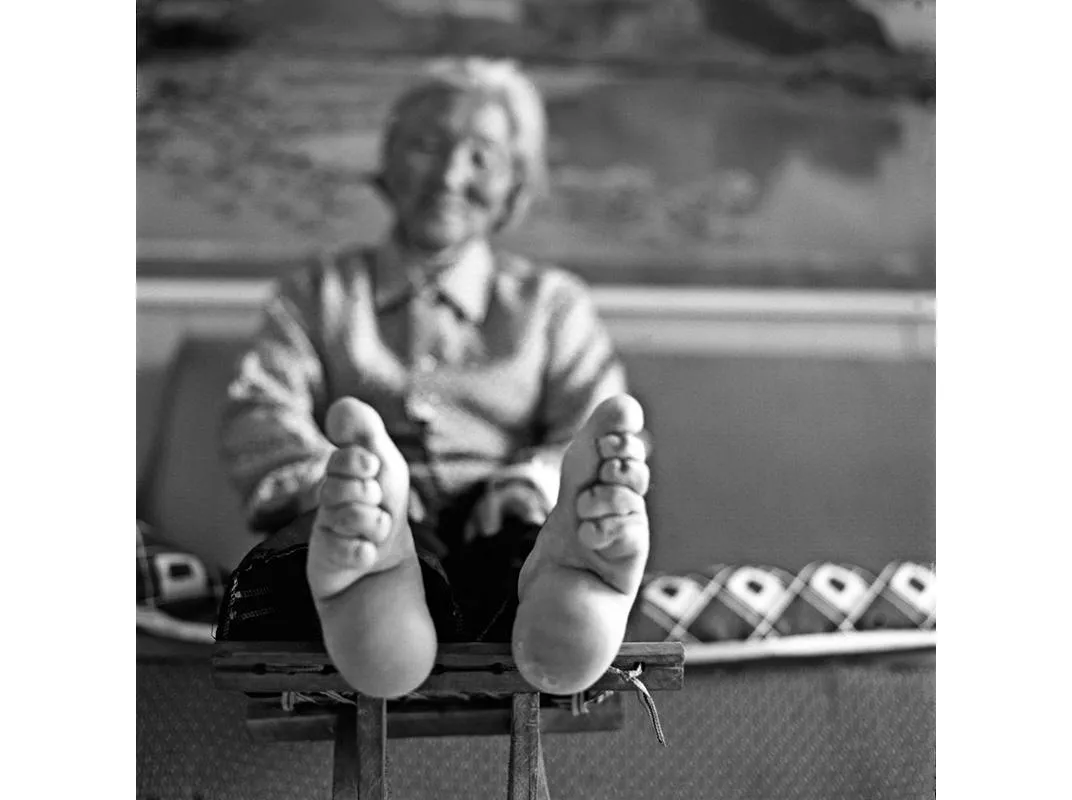

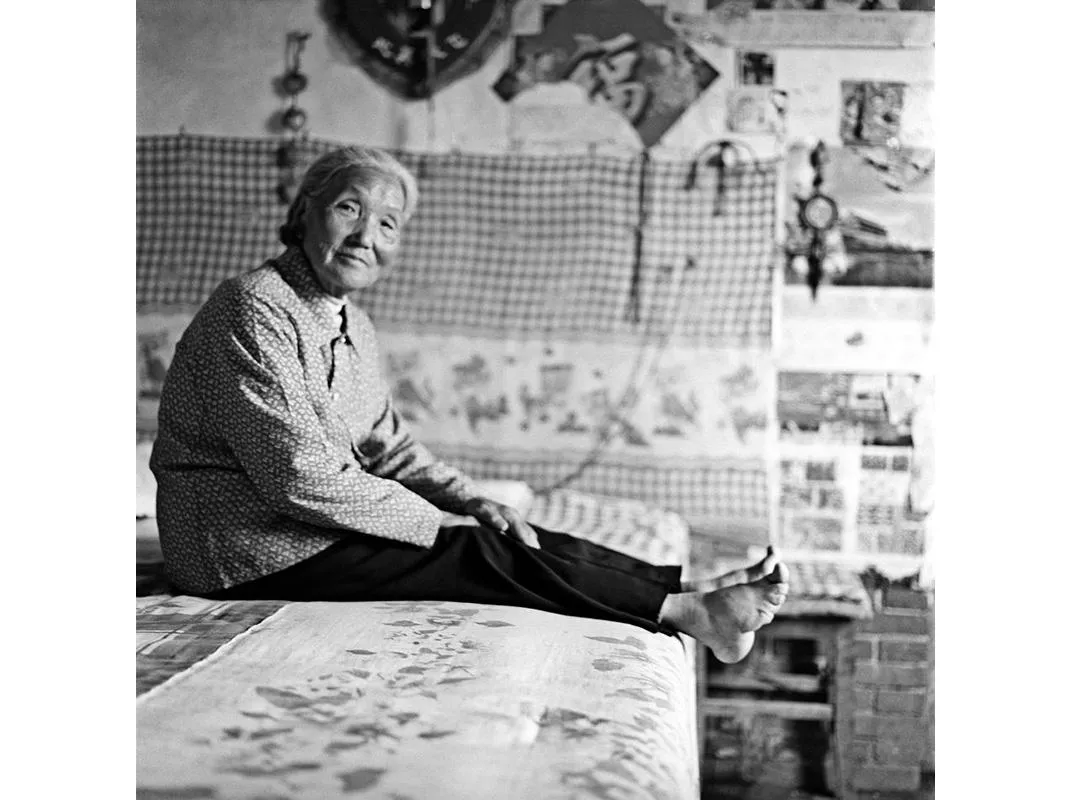

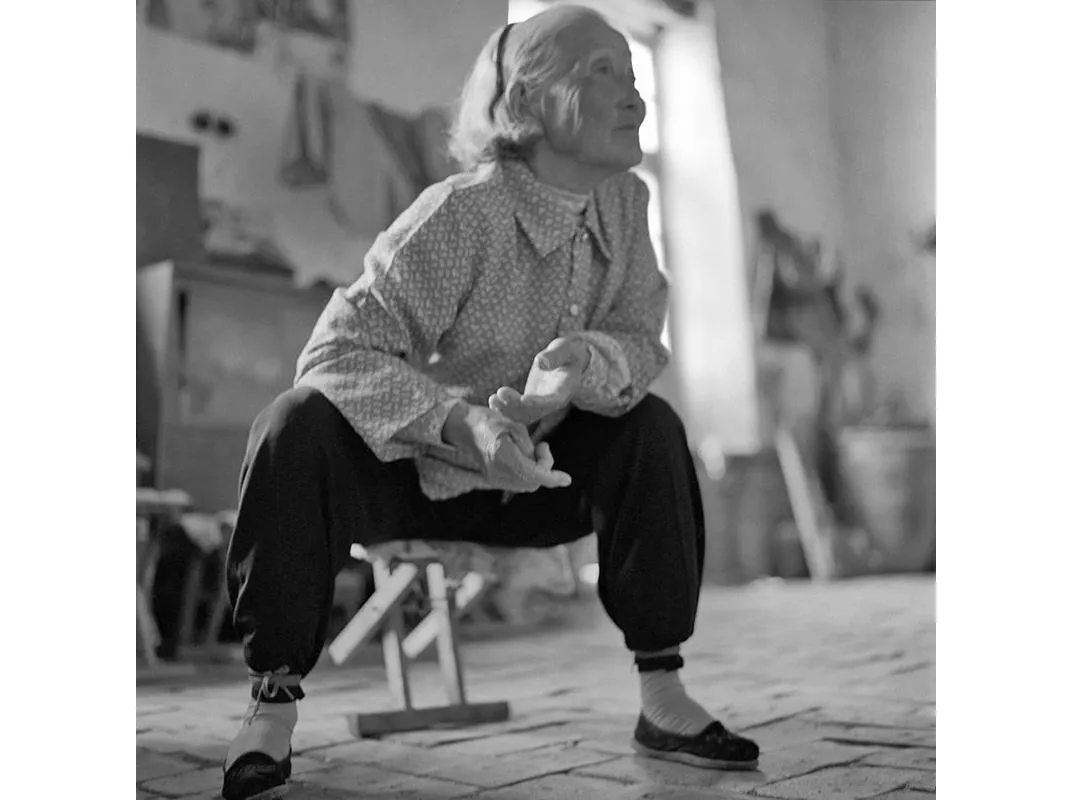

First, her feet were plunged into hot water and her toenails clipped short. Then the feet were massaged and oiled before all the toes, except the big toes, were broken and bound flat against the sole, making a triangle shape. Next, her arch was strained as the foot was bent double. Finally, the feet were bound in place using a silk strip measuring ten feet long and two inches wide. These wrappings were briefly removed every two days to prevent blood and pus from infecting the foot. Sometimes “excess” flesh was cut away or encouraged to rot. The girls were forced to walk long distances in order to hasten the breaking of their arches. Over time the wrappings became tighter and the shoes smaller as the heel and sole were crushed together. After two years the process was complete, creating a deep cleft that could hold a coin in place. Once a foot had been crushed and bound, the shape could not be reversed without a woman undergoing the same pain all over again.

***

As the practice of foot-binding makes brutally clear, social forces in China then subjugated women. And the impact can be appreciated by considering three of China’s greatest female figures: the politician Shangguan Wan’er (664-710), the poet Li Qing-zhao (1084-c.1151) and the warrior Liang Hongyu (c.1100-1135). All three women lived before foot-binding became the norm. They had distinguished themselves in their own right—not as voices behind the throne, or muses to inspire others, but as self-directed agents. Though none is well known in the West, the women are household names in China.

Shangguan began her life under unfortunate circumstances. She was born the year that her grandfather, the chancellor to Emperor Gaozong, was implicated in a political conspiracy against the emperor’s powerful wife, Empress Wu Zetian. After the plot was exposed, the irate empress had the male members of the Shangguan family executed and all the female members enslaved. Nevertheless, after being informed of the 14-year-old Shangguan Wan’er’s exceptional brilliance as a poet and scribe, the empress promptly employed the girl as her personal secretary. Thus began an extraordinary 27-year relationship between China’s only female emperor and the woman whose family she had destroyed.

Wu eventually promoted Shangguan from cultural minister to chief minister, giving her charge of drafting the imperial edicts and decrees. The position was as dangerous as it had been during her grandfather’s time. On one occasion the empress signed her death warrant only to have the punishment commuted at the last minute to facial disfigurement. Shangguan survived the empress’s downfall in 705, but not the political turmoil that followed. She could not help becoming embroiled in the surviving progeny’s plots and counterplots for the throne. In 710 she was persuaded or forced to draft a fake document that acceded power to the Dowager Empress Wei. During the bloody clashes that erupted between the factions, Shangguan was dragged from her house and beheaded.

A later emperor had her poetry collected and recorded for posterity. Many of her poems had been written at imperial command to commemorate a particular state occasion. But she also contributed to the development of the “estate poem,” a form of poetry that celebrates the courtier who willingly chooses the simple, pastoral life.

Shangguan is considered by some scholars to be one of the forebears of the High Tang, a golden age in Chinese poetry. Nevertheless, her work pales in significance compared with the poems of Li Qingzhao, whose surviving relics are kept in a museum in her hometown of Jinan—the “City of Springs”—in Shandong province.

Li lived during one of the more chaotic times of the Song era, when the country was divided into northern China under the Jin dynasty and southern China under the Song. Her husband was a mid-ranking official in the Song government. They shared an intense passion for art and poetry and were avid collectors of ancient texts. Li was in her 40s when her husband died, consigning her to an increasingly fraught and penurious widowhood that lasted for another two decades. At one point she made a disastrous marriage to a man whom she divorced after a few months. An exponent of ci poetry—lyric verse written to popular tunes, Li poured out her feelings about her husband, her widowhood and her subsequent unhappiness. She eventually settled in Lin’an, the capital of the southern Song.

Li’s later poems became increasingly morose and despairing. But her earlier works are full of joie de vivre and erotic desire. Like this one attributed to her:

...I finish tuning the pipes

face the floral mirror

thinly dressed

crimson silken shift

translucent

over icelike flesh

lustrous

in snowpale cream

glistening scented oils

and laugh

to my sweet friend

tonight

you are within

my silken curtains

your pillow, your mat

will grow cold.

Literary critics in later dynasties struggled to reconcile the woman with the poetry, finding her remarriage and subsequent divorce an affront to Neo-Confucian morals. Ironically, between Li and her near-contemporary Liang Hongyu, the former was regarded as the more transgressive. Liang was an ex-courtesan who had followed her soldier-husband from camp to camp. Already beyond the pale of respectability, she was not subjected to the usual censure reserved for women who stepped beyond the nei—the female sphere of domestic skills and household management—to enter the wei, the so-called male realm of literary learning and public service.

Liang grew up at a military base commanded by her father. Her education included military drills and learning the martial arts. In 1121, she met her husband, a junior officer named Han Shizhong. With her assistance he rose to become a general, and together they formed a unique military partnership, defending northern and central China against incursions by the Jurchen confederation known as the Jin kingdom.

In 1127, Jin forces captured the Song capital at Bianjing, forcing the Chinese to establish a new capital in the southern part of the country. The defeat almost led to a coup d’état, but Liang and her husband were among the military commanders who sided with the beleaguered regime. She was awarded the title “Lady Defender” for her bravery. Three years later, Liang achieved immortality for her part in a naval engagement on the Yangtze River known as the Battle of Huangtiandang. Using a combination of drums and flags, she was able to signal the position of the Jin fleet to her husband. The general cornered the fleet and held it for 48 days.

Liang and Han lie buried together in a tomb at the foot of Lingyan Mountain. Her reputation as a national heroine remained such that her biography was included in the 16th-century Sketch of a Model for Women by Lady Wang, one of the four books that became the standard Confucian classics texts for women’s education.

Though it may not seem obvious, the reasons that the Neo-Confucians classed Liang as laudable, but not Shangguan or Li, were part of the same societal impulses that led to the widespread acceptance of foot-binding. First and foremost, Liang’s story demonstrated her unshakable devotion to her father, then to her husband, and through him to the Song state. As such, Liang fulfilled her duty of obedience to the proper (male) order of society.

The Song dynasty was a time of tremendous economic growth, but also great social insecurity. In contrast to medieval Europe, under the Song emperors, class status was no longer something inherited but earned through open competition. The old Chinese aristocratic families found themselves displaced by a meritocratic class called the literati. Entrance was gained via a rigorous set of civil service exams that measured mastery of the Confucian canon. Not surprisingly, as intellectual prowess came to be valued more highly than brute strength, cultural attitudes regarding masculine and feminine norms shifted toward more rarefied ideals.

Foot-binding, which started out as a fashionable impulse, became an expression of Han identity after the Mongols invaded China in 1279. The fact that it was only performed by Chinese women turned the practice into a kind of shorthand for ethnic pride. Periodic attempts to ban it, as the Manchus tried in the 17th century, were never about foot-binding itself but what it symbolized. To the Chinese, the practice was daily proof of their cultural superiority to the uncouth barbarians who ruled them. It became, like Confucianism, another point of difference between the Han and the rest of the world. Ironically, although Confucian scholars had originally condemned foot-binding as frivolous, a woman’s adherence to both became conflated as a single act.

Earlier forms of Confucianism had stressed filial piety, duty and learning. The form that developed during the Song era, Neo-Confucianism, was the closest China had to a state religion. It stressed the indivisibility of social harmony, moral orthodoxy and ritualized behavior. For women, Neo-Confucianism placed extra emphasis on chastity, obedience and diligence. A good wife should have no desire other than to serve her husband, no ambition other than to produce a son, and no interest beyond subjugating herself to her husband’s family—meaning, among other things, she must never remarry if widowed. Every Confucian primer on moral female behavior included examples of women who were prepared to die or suffer mutilation to prove their commitment to the “Way of the Sages.” The act of foot-binding—the pain involved and the physical limitations it created—became a woman’s daily demonstration of her own commitment to Confucian values.

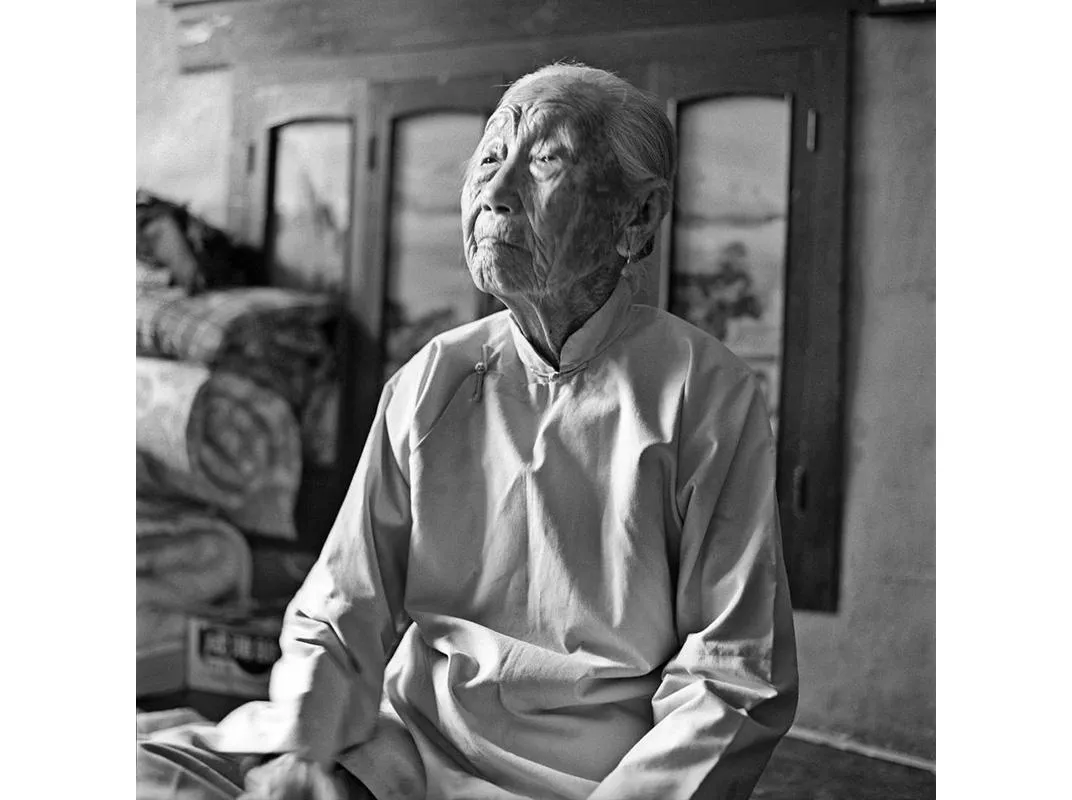

The truth, no matter how unpalatable, is that foot-binding was experienced, perpetuated and administered by women. Though utterly rejected in China now—the last shoe factory making lotus shoes closed in 1999—it survived for a thousand years in part because of women’s emotional investment in the practice. The lotus shoe is a reminder that the history of women did not follow a straight line from misery to progress, nor is it merely a scroll of patriarchy writ large. Shangguan, Li and Liang had few peers in Europe in their own time. But with the advent of foot-binding, their spiritual descendants were in the West. Meanwhile, for the next 1,000 years, Chinese women directed their energies and talents toward achieving a three-inch version of physical perfection.

Related Reads

Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet

Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amanda_Foreman.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amanda_Foreman.jpg)