Why French Authorities Placed a Young Pablo Picasso Under Surveillance

Police suspected the 19-year-old Spanish expatriate of harboring anarchist views

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8a/86/8a86ca18-e7c0-407d-a49d-f738875b4cf2/picasso.jpg)

Before Pablo Picasso became a household name, he was most familiar to the Paris police as a suspected anarchist. The assassination of French President Sadi Carnot by an Italian anarchist in 1894 had provoked a decade of social tensions in the country, on top of the infamous Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish army captain was wrongly convicted of selling military secrets to the Germans. During this period of political violence, authorities cracked down on a supposed influx of anarchist assassins and other subversive foreigners overrunning France.

Reading the record closely, one finds a remarkably aggressive program. On April 23, 1894, an official administrative note set out authorities’ guiding principles: “The police … will, using all its available officers, carry out surveillance of anarchists’ meeting places, their secret conversations, their points of connection, cabarets, etc. It goes without saying that the police employ some secret affiliates.”

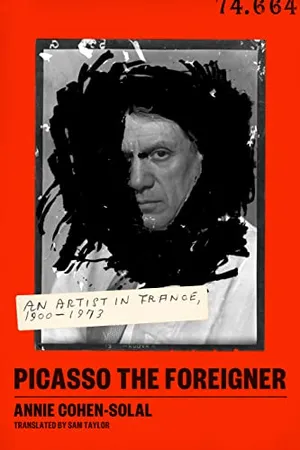

Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973

Born from her probing inquiry into Picasso's odyssey in France, which inspired a museum exhibition of the same name, historian Annie-Cohen Solal’s "Picasso the Foreigner" presents a bold new understanding of the artist’s career and his relationship with the country he called home.

Indeed, informers lurked in the 18th Arrondissement, just a few blocks away from the young Picasso’s studio on the Boulevard de Clichy, where the artist remained hard at work, fully focused on his art. “He is so meditative, so deep in silence,” his friend Jaime Sabartés noted, “that whoever sees him, from afar or close up, understands and keeps quiet. The faint murmur that rises from the distant street to the studio melts into this silence, which is broken only by the rhythmic creak of the chair on which his body moves with all its weight in the fever of creation.”

Contemplating the 64 works on cardboard that Picasso produced in just seven weeks ahead of his first show in June 1901—Absinthe Drinker, The Wait (Margot), Mother and Child, Dwarf Dancer and At the Moulin Rouge, among others—viewers encounter capsized characters painted in violent colors, with splashes of red that look like wounds. These are the people of Paris whom Picasso encountered in the rough urban streets, in the cafés and alleys of Montmartre: flamboyant dwarfs, glassy-eyed morphine addicts, flirtatious old women wearing too much makeup, weary mothers dragging their children behind them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1a/f8/1af8a9aa-541f-4156-983b-3d06530fefe0/008.jpg)

These tragic paintings reveal a world of poverty and exhaustion. Picasso had landed in this gloomy Parisian neighborhood with the help of a network of Catalans who had established themselves in Montmartre over the previous 20 years, after facing police repression of their own back home. They welcomed and helped the young, ambitious artist, who spoke not a word of French at first—and knew nothing of Parisian mores. Among this group was Pere Mañach, a brash and aggressive fellow who, in 1901, invited Picasso to stay in his apartment and organized the artist’s first major Paris show, at dealer Ambroise Vollard’s gallery.

In early May, a few hundred yards from Picasso’s studio, informers code-named Finot, Foureur, Bornibus and Giroflé—each sitting behind a pint of beer at a café in Montmartre—were listening, watching and asking questions. The four snitches were pale-faced men, diligent, dull-witted, producing notes, reporting gossip, copying texts.

The first police report on Picasso, written by Chief André Rouquier, was dated June 18. The timing here is crucial. Despite the prior existence of information on Picasso compiled by the friendly informers, it was a newspaper article published in Le Journal on June 17 that triggered and shaped the final document: the critic Gustave Coquiot’s review of Picasso’s joint exhibition with Francisco Iturrino, which had opened a week earlier at the Vollard gallery.

Coquiot praised Picasso as a “frenzied lover of modern life” and predicted that “in the future, the works of Pablo Ruiz Picasso will be celebrated.” But Rouquier seized on one point from the review: the lowliness of the artist’s subjects, who were “girls, fresh-faced or ravaged-looking,” such as “the sloven, the drunkard, the thief, the murderess,” or “beggars, abandoned by the city.” Then, building on the informers’ reports that had been gathering dust for several weeks, the chief quickly concocted a summary: “Picasso recently painted a picture showing foreign soldiers hitting a beggar who’d fallen to the ground. Moreover, in his room there are several other paintings showing mothers begging for charity from bourgeois men, who push them away.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/99/2a99101e-e4c2-47c6-b7a8-894045c237f2/012.png)

Swept along by the hysteria of the times—much like Maurice Barrès, a nationalist politician who frequently raged against “the foreigner [who], like a parasite, is poisoning us”—Rouquier deftly transformed Picasso’s paintings into evidence that could be used against him.

The policeman then stirred in bits of gossip gathered from the concierge of the apartment building where the painter was staying and added sweeping allegations and slanders: “He is visited by several known individuals. He receives a few letters from Spain, as well as three or four newspapers whose titles are unknown. He does not appear to use general mail delivery. His comings and goings are highly irregular; he goes out with Mañach every evening and does not return until quite late at night.” The report ended with this stunning payoff: “From the foregoing, it is concluded that Picasso shares the ideas of his compatriot Mañach who is granting him asylum. Consequently, he must be considered an anarchist.”

This conclusion blithely ignored the fact that Finot, Foureur, Bornibus and Giroflé had never spotted the artist at any anarchist meeting. The only thing he did was sign—along with many others—a December 1900 petition for an amnesty in support of Spanish deserters from the 1898 Spanish-American War. Sure enough, Picasso’s lack of military experience, along with later his decision not to volunteer to serve in the French Army during World War I, would be held against him in the next few police reports. On June 18, Rouquier—driven by his professional conscientiousness, his personal zeal and the generalized hysteria of the Third Republic—filed his report. A few days later, his direct superior would furiously underline in red pencil the words “he must be considered an anarchist.” (In truth, Picasso became a member of the French Communist Party in 1944.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0b/76/0b765cf2-eb73-4f00-9a1f-236f08b59e9e/014.jpg)

Today, the 64 paintings completed in spring 1901 by an intensely focused 19-year-old artist for his first exhibition in a Parisian gallery are considered undisputed masterpieces and sell for stratospheric sums. In 1901, however, those paintings were used as sufficient cause to surveil and harass the young man whose only fault was to have accepted the support of the Catalan colony. “Throughout the last two centuries, when examining French officialdom,” wrote the sociologist Gérard Noiriel, “we continually encounter this obsessive fear of ‘non-native cells’ … that might pursue political ends.”

In this way, the blessing of the Catalan network that welcomed Picasso to Montmartre—that quarter of Paris where “the world of pleasure met the world of anarchy,” as the French historian Louis Chevalier put it—would very quickly become a curse, as Picasso continued to be surveilled by the police for the next 40 years.

Excerpted from Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973 by Annie Cohen-Solal. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dfsa.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dfsa.png)