Spoken Latin Is Making a Comeback

Proponents of the teaching method argue that it encourages engagement with the language and the ancient past

It’s a sweltering summer day in Rome, so hot that the lines for the city’s free water fountains stretch as far as the eye can see. A group of American high schoolers is clustered under one of the few shade-providing trees in the Roman Forum. The students are huddled over their books, trying to piece together a Latin passage.

As the teenagers hunt for sentences’ subjects and direct objects, noting the use of the accusative case or struggling with the meaning of a word, their teacher offers advice primarily in Latin: “Quid significat?” they might ask. (“What does this word mean?”) Responding to queries about sentence structure or whether an adjective references a certain person, students respond “ita” for “yes” and “minime” for “no.”

The fact that these individuals are speaking Latin, a language most often seen in written form, is unusual in and of itself. But the more important aspect of the exercise is how the students are interacting with the text in a living way. They’re reading Plutarch’s depiction of Cicero’s death in the very place where, in 43 B.C.E., the famous orator’s cut-off hands were placed as a warning that the Roman Republic was ending and the empire was beginning.

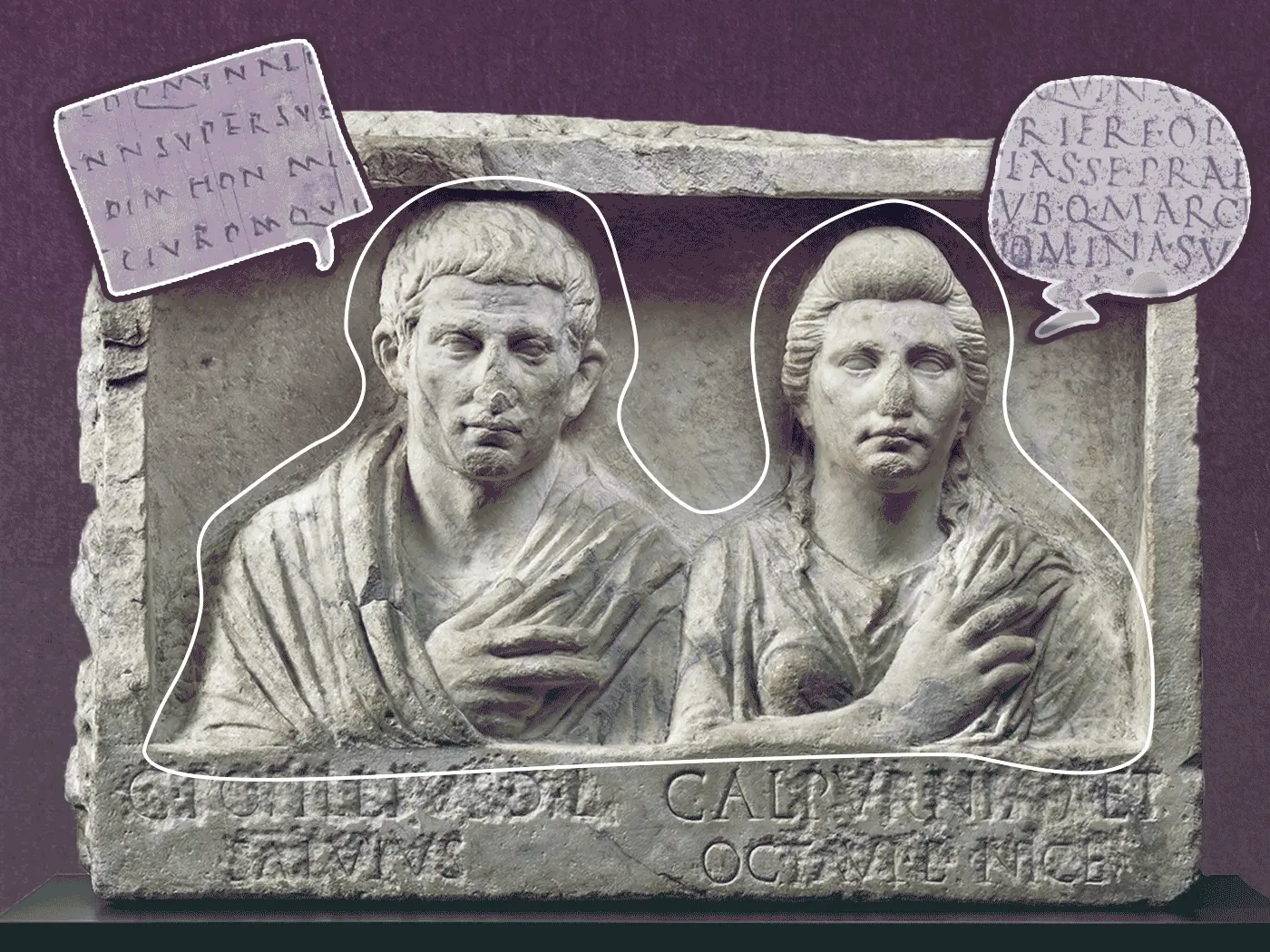

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/f2/45f291b7-7df4-43ad-b091-b03f553e94b0/35654258830_0dad893cc7_k.jpg)

Though Cicero didn’t exactly rise from the dust of the forum that July 2022 day, one instructor refers to the learning experience as a type of a séance. The excitement in the air is palpable as ancient Rome becomes less a place of words and books and more that of living, breathing humans. It’s hard to imagine the bustling forum as it once was—a site of power, religion and commerce, where Latin was spoken in a functional way. But as the teenagers speak the language, relishing its intonations and cadences, that image slowly clicks.

These students are part of the Paideia Institute’s flagship Living Latin in Rome program, which offers participants two weeks of intensive study in the heart of the ancient civilization. Headquartered in New York, the nonprofit promotes classical languages and literature through immersion programs held abroad, digital outreach and educational events in the United States. In addition to Living Latin in Rome (available for both high schoolers and students above age 18), Paideia offers Living Greek in Greece and Living Latin in Paris. All of these courses share the same underlying philosophy, encouraging students to actively use Latin and ancient Greek as living languages. Technically speaking, both are dead languages, meaning they’re “no longer learned as a first language or used in ordinary communication,” per Encyclopedia Britannica.

“Learning to express oneself in these long-dead languages fosters a unique personal connection with the ancient world that is powerful and enduring,” notes the institute on its website. “This relationship is further enriched when ancient literature is read, heard and spoken amidst the beautiful backdrop of the monuments of Greek and Roman culture in Greece and Italy.”

Teaching Latin in an active way isn’t exactly a new idea. Around the turn of the 20th century, W.H.D. Rouse, headmaster of the Perse School in Cambridge, England, advocated for a “direct method” of teaching in which students refrained from using English, instead speaking almost exclusively in ancient Greek and Latin.

Decades later, in the late 1970s, Father Reginald Foster started offering free spoken Latin courses almost every summer. The American Catholic priest was known in part for his ludi domestici, or “games to play at home,” which replaced homework with more engaging exercises. Paideia—founded by two of Foster’s students, Jason Pedicone and Eric Hewett, in 2010—continues this tradition by incorporating the game “Quis sum?” (“Who am I?”) into its lessons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9f/45/9f457790-13f4-4978-8e81-4ad2fb401d74/reginald_foster_certamen_capitolinum_1972_2.jpeg)

“For most classicists trained in the United States or in Great Britain, Latin was a learned, non-spoken language; it was not a language that one could converse in, like French or Spanish,” Leah Whittington, a literary scholar at Harvard University, told Smithsonian magazine in 2020. “But for Reginald, Latin was an everyday functional language that he used with his friends, his teachers, his colleagues, with himself and even in his dreams.”

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century C.E., Latin began to fall out of use—a decline solidified between 600 and 750. The Roman Catholic Church kept the language alive, but spoken Latin more broadly was eventually replaced by the Romance languages.

During the medieval period, students used a “direct method” of learning Latin, in which only “easy materials” were used in the first years of study, wrote religious scholar William Most in a 1962 teaching manual. Writings by Julius Caesar and Cicero were readings to work toward, not commonly taught texts as they are today. As Most explained, “The result was that when [students] finally did begin to study these works, [they were] in a good position to gain a real appreciation of them, for [they] had learned by that time to read, write and speak Latin with fluency.”

Latin curriculums changed dramatically in the 16th century, when the “grammar analysis” method, as Most calls it, advocated as “its chief objective” the translation and parsing of “a certain number of Latin lines per day.” Today, this method remains the framework of much Latin instruction. But spoken Latin is in becoming increasingly common in classrooms. According to a 2019 survey of 95 Latin teachers, the most frequently cited change in their teaching methods in the past 10 to 15 years was the introduction of active Latin techniques.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c2/af/c2af051d-d132-4221-91cd-5079c2e20476/screenshot_2023-02-13_at_111156_am.png)

Traditional teaching methods, like asking students to conjugate a verb on the spot or translate a complex Latin passage in front of their peers, can be tedious at best and nail-bitingly nerve-racking at worst. Spoken Latin classes engage participants in a different way, emphasizing understanding of and interaction with the language rather than rote tasks based on memorization and grammar. Instead of transitioning between Latin and English, spoken Latin keeps the cognition all in one language.

Writing for the Antigone journal in 2021, Melinda Letts, a Greek and Latin instructor at Jesus College—the only sub-school at the University of Oxford to teach classical languages in an active manner—described what spoken Latin looks like in her classroom. An average session begins with a greeting in Latin and the reading of a short passage. Discussion of the text, from its meaning to its vocabulary, takes place in Latin, with the teacher providing Latin synonyms of words the students don’t understand rather than their direct English translation.

The term “spoken Latin” is itself up for debate. Letts and Pedicone don’t use the descriptor, as it implies a constant use of Latin in the classroom. Pedicone prefers “living,” an adjective that reflects the full swath of activities Paideia offers, from memorization and theatrical performances to reading literature out loud.

Letts, meanwhile, uses the phrase “active Latin.” “We don’t call it immersive Latin because they can’t have [a fully] immersive experience,” she says. “They come in for their Latin lesson and go out for the rest of the day, but the lesson itself aims to be immersive.”

The Oxford teacher took an interest in active Latin after watching her students’ intense focus on translating texts. It was a process more akin to “code breaking” than really engaging with the literature, she recalls. In the Antigone article, Letts added that her goal “is to do everything I can to help [students] leave ‘translating’ behind and start to read the literature.”

Some of Oxford’s classics undergraduates study ancient Greek or Latin during high school, but others have no previous formal training. “It was increasingly clear to me that even students who had done Greek and Latin A-levels”—equivalent to Advanced Placement courses in the U.S.—“were often a long way from being able to read the language,” Letts says. “I began to think of trying to incorporate an oral element into my teaching, but I didn’t know how to go about doing so.”

Letts also drew inspiration from a weeklong spoken Latin trip hosted by Oxford Latinitas, a student organization-turned-company dedicated to studying ancient languages with the active method. The group was looking for faculty members to participate in the visit to Rome, and Letts, though nervous, jumped at the chance.

“For the first few days, it was uncomfortable, and it was frustrating,” she says. “I was longing to participate in the conversation, but I was having to just get used to my brain finding the words.”

After the 2018 trip, Letts started incorporating active Latin into her classes, producing what she felt were great results. Jesus College officially launched its active Latin program in 2021.

Initially, scholar and educator Skye Shirley, who specializes in texts written by women in Latin, didn’t love the language so much as the mythology of ancient Rome. But spoken Latin showed her a different side of the discipline. Now, she runs Lupercal, a Latin reading group for women and nonbinary Latinists that employs spoken language, and a Women Latinists summer course in Florence through Forte Academy. In meeting handouts, she includes footnotes with Latin synonyms and scene-setting questions that help the group get accustomed to using Latin in conversation, not just readings paired best with a dictionary.

Shirley’s focus is on “comprehensible input,” or using the language in a way it can be understood rather than simply speaking it.

“You can have people read Latin aloud, and [listeners] aren’t picking up anything of what’s going on,” she says. “Watching two [or] three people pontificate on Latin is not comprehensible input. It’s understanding 90 percent of the words in any given passage.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/27/c327a950-29ac-4b4b-aeaa-0bbf263cb4f0/35221823624_dd6f296eab_k.jpg)

For Shirley, the process of spoken Latin has built up her confidence in the language and improved her reading skills. Letts, who started learning Latin at age 6, also says the active learning method has transformed her understanding of the language. Now, she can read any Latin text without mentally translating it.

Other active Latin students who watched their abilities evolve after they started thinking about the language in a new way echo Shirley’s and Letts’ praise. Keegan Potter, a high school Latin teacher at Crossroads School for Arts and Sciences in Santa Monica, California, studied Latin in a traditional classroom. That teaching method, he says, appeals most to a particular kind of student: one who wants to gaze at grammatical charts and look up endless lists of terms.

This description didn’t fit Potter. He came to the realization after participating in a rusticatio, a seven-day workshop in which participants speak entirely in Latin, when he was a young teacher.

“I didn’t really know Latin as well as I probably should have,” Potter says. But after the workshop, he “was hooked by it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/8d/958da0fc-326c-4e9e-bab0-274a1b0a54e6/29757922471_4bde463d7f_k.jpg)

Potter now employs active Latin techniques in his classes. Like Shirley, his focus is comprehensible input, with a goal of trying to get students to understand simplistic questions in Latin: for example, what’s happening to this person, and who is performing a specific action? He aims to conduct roughly 90 percent of every class session in Latin.

Over time, Potter has watched demand for his courses spike. His highest-level Latin class, the equivalent of an Advanced Placement course, enrolled 18 students in the 2022 to 2023 school year—the highest enrollment for an upper-level Latin course that the school has seen “in a very long time,” he says. Nationally, a 2017 survey found that just 2 percent of grade school students taking foreign language courses were studying Latin. Comparatively, 67 percent were enrolled in Spanish.

Spoken Latin is as much the subject of controversy as it is a success story. Pedicone lumps naysayers into two camps: those who argue that intensive Latin programs aren’t intensive enough, as most don’t require students to speak the language exclusively, and those who will always insist on the grammar-translation method as the pinnacle of Latin pedagogy.

Paideia itself has proved controversial for other reasons. In 2019, alumni and former staff criticized the nonprofit for failing to provide a safe space for women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community and other marginalized groups. In response, the institute’s leadership apologized and pledged to improve their diversity and inclusion efforts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d9/39/d9391930-f781-4525-9b61-aafea6b1fc33/35252478093_67466d6c28_k.jpg)

Both spoken and traditional Latin-learning techniques have their pros and cons. Pedicone once met a student who had graduated from a high school that taught him to speak Latin but not about the accusative case. The alternative isn’t necessarily better.

“What I worry about with just doing traditional hardcore grammar translation is that it can be boring, and some students don’t respond well to that,” he says. “But I also think philology is really important—the skills you get from learning how to do close readings and diagram sentences. You’re really missing out if you’re not getting any of that and learning how to order a hamburger in Latin.”

Perhaps the biggest benefit of active Latin is its ability to increase students’ enjoyment of the language. “You cannot arrive in any method on day one and read Plato in the original [Greek],” Letts says. “But these immersive methods actually have a student leave their first lesson having read and understood some continuous prose. And that’s exciting for them. They think, ‘I can read the Greek. I can say something.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)