Monroe Township, Missouri, was a hotbed of secessionism, but Union sentiment ran strong in John Gudgell’s household. Just days after federal troops arrived in the area in mid-June 1861, the family’s youngest child enlisted in a home guard unit. By fall, 14-year-old Julian Gudgell was determined to join a proper regiment. Although his father foiled his first attempt, he ran away again a few weeks later and managed to enlist in the 18th Missouri Infantry. On paper, he claimed to be 17.

Julian was one of more than 200,000 youths below the age of 18 who served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Constituting roughly 10 percent of Union troops and most likely a similar proportion of Confederate forces—though surviving records allow for less certainty on the rebelling side—these young enlistees significantly enhanced the size and capabilities of both armies. They also created a great deal of drama and chaos, upending household economies by absconding with vital labor power, causing loved ones untold anxiety, and sometimes sparking dramatic showdowns between military and civilian authorities.

Family members desperate for their sons’ release from service confronted officers in military camps; petitioned elected representatives and government officials; and appealed to judges for writs of habeas corpus, which compelled military officers to appear in court alongside underage soldiers and defend their enlistment. When such efforts failed, many embarked on costly—and often futile—quests, chasing after regiments on the move, combing city streets near enlistment offices or even traveling to Washington to plead their case in person. These conflicts had far-reaching consequences for the individuals and families involved, as well as for the battered nation that emerged from the war. Not only were thousands of minors legally emancipated from parental control through enlistment, but the federal government also centralized power by rewriting militia laws and preventing state and local courts from using the habeas process to check potential enlistment abuses.

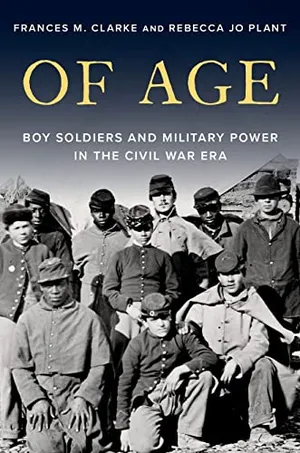

Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era

An innovative study of underage soldiers and their previously unrecognized impact on Civil War era America

Consider John Gudgell’s attempts to recover his son. He first sought the help of a general stationed in the area, who assured him that Julian would soon be sent home. Six months later, though, the boy was still in the service. John then wrote to Missouri Representative Francis P. Blair Jr., calling himself a stalwart “union man” and saying he would not be trying to intervene if Julian were “older and more experienced.” No matter what arguments John made or whom he petitioned, he could not get his underage son discharged.

Given that the law was on John’s side, this process shouldn’t have been so hard. When Julian enlisted, minors below the age of 21 legally needed the consent of a parent or guardian to enlist in the Union Army. In February 1862, Congress lowered the bar to 18, but at 14, Julian fell well below that threshold. John even managed the rare feat of obtaining the support of Julian’s captain, who wrote to the United States Adjutant General’s Office that a discharge would be in keeping with regulations. Besides, the captain added, “such boys are of little or no use to the army in the field.” Still, Julian was not released.

His service history suggests why. He fought in the Battle of Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee in April 1862 and earned a promotion to corporal in early 1863, soon after his 16th birthday. Not so much as an absence due to illness marred his record. While Julian may have been unusually capable for one so young, many underage soldiers distinguished themselves in similar ways. A large majority of them served as regular soldiers, not musicians, and around 80 percent were 16 or 17 years old. But even the youngest and smallest boys, who were treated as pets of their regiments—allowed to ride while others marched, kept behind the lines while others fought—performed important roles. They helped carry the wounded from the field, ran messages, filled canteens, tended horses, built campfires, cooked, mended clothes and lifted men’s spirits with their childish antics. They may not have been of age, but they were of crucial use, which is precisely why the military was loath to release them.

This was especially true among the Union forces—a finding that at first might seem counterintuitive, even confounding. After all, the U.S. boasted roughly 3.5 times as many white men of military age as the Confederacy. To address its population disadvantage, the Confederate Congress resorted to far-reaching measures, achieving a substantially higher rate of service among eligible men than the U.S. could ever claim. The Confederacy adopted a policy of universal conscription in April 1862; in February 1864, it lowered the age of conscription from 18 to 17. At the same time, some Confederate states enrolled boys as young as 16 for service in state-controlled units. Meanwhile, the U.S. maintained a minimum age of 18 for voluntary enlistment and only drafted those aged 20 or above. Given all this, it makes sense that many Unionists accused Confederates of “robbing the cradle and grave” to fill their ranks.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d3/85/d3859063-960d-465c-8c2e-22092b291a86/to-arms.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/8d/018d2f12-60e0-4a24-94ca-3ee9214ebe98/stret.jpg)

Yet closer scrutiny reveals a more complex history. Most leaders balked at the idea of conscripting youths below 18 directly into the Confederate Army, insisting that such a measure would amount to “grinding the seed corn”—destroying the South’s future. Instead, they enrolled 17-year-olds in state reserve units, which generally entailed less dangerous work that was closer to home. Even near the war’s bitter end, when the Confederates enacted legislation allowing for the enlistment of enslaved people, they declined to conscript boys below age 18 into the regular army. Of course, many tens of thousands of underage youths—possibly over 100,000—served in the Confederate Army nonetheless. But all things considered, it is the Confederacy’s efforts to shield the young from hard service, more than its attempts to mobilize them, that demand explanation.

If inherited notions of the Confederate Army dragooning boys into service are erroneous, so too is the belief that underage enlistment in the U.S. was mainly limited to drummer boys. Drawing on official military records, historians have long held that children younger than 18 made up only a minuscule portion of all Union enlistees—less than 2 percent. Yet when soldiers’ reported ages are checked against census records and other sources, it becomes clear that the true history of underage enlistment has been obscured by an epidemic of official lies. While most young enlistees shaved somewhere between a few months to a few years off their actual ages, the more extreme cases—like that of 11-year-old George S. Howard, who enlisted in the 36th Massachusetts Infantry by claiming to be a 19-year-old—are positively jaw-dropping. Codified as facts by enlisting officers who often knew better, the lies told by underage boys were subsequently incorporated into historical accounts, skewing our view of the Union Army up to the present day.

Not only did boys and youths enlist in greater numbers than generally thought on both sides, but their service also preoccupied contemporaries to a greater extent than historians have recognized. As soon as the fighting began, petitions and affidavits seeking the release of underage soldiers started pouring into Washington—so many that in September 1861, the War Department simply decreed that it would no longer discharge soldiers on the grounds of minority. But until late 1863, judges in state and local courts continued to hear habeas cases involving minor enlistees, discharging them more often than not. In August 1861, a headline in the New York Times pronounced the “plea of infancy” in courtrooms “an epidemic.” Endlessly litigated in courts, debates over underage soldiers also played out in the press, the halls of Congress, government offices, and military and medical circles. All the while, writers, artists and musicians plied the nation with idealized depictions of heroic drummer boys and young soldiers, which appeared in every imaginable corner of the culture—from paintings and lithographs to sentimental poems, songs and plays.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/90/a2907892-4f99-4b76-9168-548a81bb502f/sfads.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/7a/587a5c44-c357-4ad1-88d9-32817745ac51/clarke__plant_fig_61_of_age_9780197601044.jpg)

As a political and cultural symbol, the boy soldier or drummer boy resonated in the U.S. in ways it simply could not in the Confederacy. Rooted in an artistic tradition that dated back to the French Revolution, the figure embodied the democratic republic that the nation imagined itself to be—youthful, incorruptible and forward-looking. These were not the values most prized by the Confederate States of America, a nation founded by self-styled patriarchs seeking to uphold a hierarchical social order based on slavery. Like Unionists, Confederates celebrated particularly heroic youths as evidence of their people’s unconquerable spirit, but only in the U.S. did the generic boy soldier or drummer boy become a symbol that personified the nation.

Likewise, only in the Union states did youth enlistment become a bureaucratic nightmare and a pressing legal question. That’s because the debate over underage enlistees in the U.S. was simultaneously a debate over the limits of military power. It all boiled down to whether the government could legally breach the relationship between a father and a minor son, holding an underage enlistee to service regardless of parental wishes. In other words, contests over the status of enlisted boys and youths inevitably raised fundamental questions over how much authority household heads, communities and states could expect to retain while fighting a prolonged and bloody war.

The Confederacy was also wracked by disputes over how much authority should be ceded to the central government and the military. But in the Confederate states, legal conflicts over the concentration of power rarely centered on underage enlistees. Owing to the comprehensive nature of Confederate conscription, civilians more typically sought the release of absent husbands and fathers—adult male providers—rather than underage sons. In any event, families had an easier time recovering youths who enlisted without parental consent. The suspension of habeas corpus was more episodic and less effective at blocking such cases than in the U.S., and the Confederate government neither enacted laws nor issued general military orders designed to prevent minors’ release.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/e4/1fe4a97b-d8c9-4fbc-9f26-8e53e599408d/shiloh.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6f/8b/6f8b2b09-8116-4ca5-97a1-2e0bf2024d8b/clarke__plant_fig_52_of_age_9780197601044.png)

What happened to John and Julian Gudgell is thus very much a Union story. Still on the rolls in late 1863, Julian re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer and was rewarded with a 30-day furlough. But once he returned home, his father decided to claim and hold what he saw as rightfully his. The young soldier with a previously unblemished service record failed to return to his unit.

Julian found himself caught between two masters, both relentless in their demands for his presence and service: his father and the U.S. federal government. His decision to privilege filial obedience cost him dearly: Deemed a deserter in April 1864, he was arrested in December, just a week after his father died and less than a month after he turned 18. A court martial panel heard his case in March 1865 and sentenced him to a dishonorable discharge and a year in prison. Two months later, some leading citizens from Julian’s hometown managed to get the sentence commuted, assisted by a brigadier general who attested that Julian had been a good soldier and “would not have stayed at home but at the insistence of his father.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/ba/c4ba38e0-8679-4c13-8685-1e61cba763d7/2560px-drummer_boys_off_duty_playing_cards_in_camp_winter_of_1862_lccn00651621.jpeg)

While Julian regained his freedom, he would never reap the financial rewards and public accolades afforded to other veterans. His dishonorable discharge barred him from receiving a military pension, and a regimental history published in 1891 fails to list him as a surviving member, even though he was still living at the time. The takeaway seems clear: No matter a soldier’s underage status, no matter his parents’ wishes, he would be held to account if he violated his military contract. Over the course of the war, thousands of Union soldiers and their families would learn this same hard lesson about the growing primacy of federal and military power.

Adapted from Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era by Frances M. Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Frances M. Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ef/37/ef376ec4-bcdc-4b15-9cd0-294dbb7673cb/boys.png)