On the unseasonably hot Friday morning of December 4, 1812, the 193-ton brig Isabella prepared to depart from Port Jackson Harbor in the British convict colony of New South Wales, in what is now Australia. The vessel’s ultimate destination was London, via Cape Horn. Among the 54 people on board were the brig’s captain, George Higton; Scottish Lieutenant Richard Lundin; former convict Joseph Holt, his wife, Hester, and son, Joseph; convict transport ship captain Richard Brooks; former convicts Samuel Breakwell and Henry Browne Hayes; and passengers William Mattinson and Joanna-Ann Durie.

A few weeks into the journey, the Isabella nearly crashed into Campbell Island, south of New Zealand, due to Higton’s incompetence. It then barely survived a tempestuous sail around Cape Horn. Now, the ship was heading for Rio de Janeiro, hoping to sail between the Falkland Islands and South America. But instead of captaining the brig and ensuring the safety of his crew and passengers, Higton got drunk and went below to visit Mary Bindell, a former convicted prostitute who welcomed him into her bed.

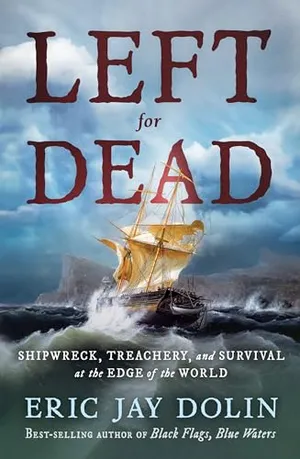

Left for Dead: Shipwreck, Treachery and Survival at the Edge of the World

The true story of five castaways abandoned on the Falkland Islands during the War of 1812―a tale of treachery, shipwreck, isolation, and the desperate struggle for survival.

Before 2 a.m. on February 8, 1813, in a sickening replay of the earlier alarm off Campbell Island, Lundin was aroused by yelling and scurrying on the main deck. Through the gloom of a moonless night, land was visible very close by. With Higton drunk and otherwise occupied, Brooks had taken command and was trying his best to steer the Isabella clear of danger. Finally, believing that he had gained a moment of reprieve, and that the brig would soon pass by land, Brooks went below to don warmer clothes. No sooner had he descended to his cabin, though, than cries rang out: “Rocks on one side and breakers on the other!”

Lundin rushed to get Brooks, but at the moment he reached the main deck, the Isabella crashed into a rocky reef “with dreadful force,” he later recalled. This collision unshipped the rudder, leaving the Isabella unable to steer, and thus at the mercy of wind and waves. Another swell lifted the brig off the rocks for a few moments, only to launch it into other ones as soon as the next trough arrived, forcing everyone on board to grab hold of something to avoid being thrown about or pitched into the water.

Down below, Holt had roused his family members, who promptly sank to their knees to pray for “God’s mercy and assistance,” as he wrote in his memoirs. When the brig crashed into the rocks a second time, Hester placed her son in between her and her husband, saying, “Let us all, linked in each other’s arms, go to our watery graves together.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/77/3a77851c-e00f-4dfe-a3b6-68b543df9180/view_of_sydney_harbor_1811_rumsey_copy.jpg)

Meanwhile, the Isabella floated free of the rocks but was still being propelled rapidly toward the looming shore into increasingly shallow waters, with massive waves crashing all around. The sea was covered with foam as far as the eye could see. The few sailors who were responding to Brooks’ commands climbed aloft to square the yards so that the brig could run toward land. Finally, the Isabella struck fast on a rock ledge. It was high tide, so the brig was much closer to shore than if the tide had been out, and the tip of the bowsprit reached the beach. Brooks then yelled over the din, “There is now no danger of our lives.” He ordered the men to cut away the mainmast, which fell toward the land.

At this point, the true nature of some of the crew and passengers came to the fore. Abandoning all sense of order or control, a few of the sailors careened through the brig, demanding liquor from the frightened passengers. According to former convict Mary Ann Spencer, one of the men entered her berth, grabbed a glass of rum from her hand, emptied it and dashed it upon the deck, exclaiming, “We shall have no more use for glasses, for this is the last time, either at sea or on shore, that we shall ever drink.”

Lundin and Brooks, meanwhile, were trying to organize the people on board and lower down a small boat so it could be rowed to shore, with women and children leaving first. Once the boat was in the water and tied off with a towrope, however, Hayes, Breakwell, Mattinson and two Royal Marines pushed the other passengers aside and commandeered the vessel, jumping in and taking with them three of the Isabella’s four oars.

Then the scoundrels noticed that the boat’s plughole was open, leading it to take on water at a rapid rate and slowly sink. While the men frantically searched for the plug, Lundin learned its location from the carpenter and told those in the boat—an act he later much regretted. Rather than reconsider their action, the deserters plugged the hole and released the towrope, leaving all of those still on the Isabella to their fate and filling them with “rage and disappointment” over this “unexampled treachery.”

All hands who were not drunk now focused on launching the Isabella’s longboat, which required great effort, as it was a very bulky, heavy vessel designed to carry lumber and water. It was loaded with supplies, including flour, biscuits and other provisions quickly brought up from below. Once the longboat was filled, Brooks and a few of the marines attempted to set out for the beach, but they found it nearly impossible to maneuver the vessel with only one oar. Suddenly, Lundin remembered the beautifully carved paddles he had acquired from South Sea Islanders, which he was taking home as souvenirs. Retrieving them from his cabin, he pitched them into the longboat, which was still alongside the brig.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8a/30/8a30f39d-af91-4521-92de-9ed5c836ac3b/barnard-narrative-map-copy.jpg)

Doing their best, the marines managed to use the one oar and the souvenir paddles to muscle the boat along the shore and around a small promontory, on the other side of which they landed, secured the boat and carried the provisions ashore. They had wanted to return to the brig, but they would not stand a chance of making way against the wind with such a poorly propelled vessel.

Soon, none other than the five deserters joined them, having landed a little way down the beach. Brooks harangued Hayes, the apparent ringleader of this despicable bunch, telling him that what he had done was disgraceful. Hayes parried the verbal blow, expressing great “effrontery, pleading self-preservation,” which, Lundin later commented, was the “first law of nature, which, to persons of his selfish and despicable principles, will indeed ever be a primary consideration.”

Walking back toward the stricken Isabella, Brooks and the marines were cheered by the sight of passengers making it ashore. A hawser, or thick rope, was strung to the wreck and equipped with a jury-rigged bosun’s chair, allowing first the women and children to escape and then the others. Despite her very pregnant state, Durie, wife of a Scottish military captain, “supported herself with great fortitude” during this ordeal, according to Lundin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/90/039083be-b5cf-4ea5-9019-d7c8c26b1b29/brooks.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/12/6012b034-2bc1-4bce-a357-fd367210f789/joseph_holt__copy.jpg)

Holt helped see that his wife and son made it to the beach, but when he asked two of his servants to help him gather his belongings to take them off the brig, they ignored him and joined the marines and sailors in their bacchanalian debauchery. Only Holt’s third servant, an old and infirm man, lent a hand. By the time the dawn light illuminated the scene, everyone had disembarked. “Never,” Lundin mused to himself, “did a weary traveler reach his destined rest with more heartfelt joy than we did, now cast upon this desert shore.”

Soon after Holt and Durie’s husband, Robert, made it to the beach, they searched for their wives, who had been separated from them in the confusion. They found the women sitting together on a gentle rise, which Holt dubbed “Sorrowful Bank.” Durie held out a bottle of rum and urged Holt to take a swig. “I will, madam,” he responded warmly, “for it is wanted to me, as I have not broken my fast this day.” Thus began the stay of the Isabella’s crew and passengers on Eagle Island (now Speedwell Island, one of the Falklands), located about 110 miles from where the American sealing vessel the Nanina was holed up.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/32/56/325683f5-6e43-4c38-833d-fa9cd6737490/isabella_anchor_2_may.jpeg)

When the Nanina discovered the British castaways in early April, its American crew offered to rescue them, even though it would cut short the sealing trip. To compensate for this loss, the Americans asked the British to give them all of the Isabella’s cargo. Although the British greatly outnumbered the Americans and could have easily overpowered them, they accepted the terms of the deal, thankful for this humanitarian gesture in the midst of the War of 1812.

But when a British warship, the Nancy, arrived on the scene about a month later, its captain voided the agreement between the castaways and the Americans, seized the Nanina as a prize, and declared the Americans prisoners of war. Even worse, when the Nancy sailed from the Falklands with its prize and its prisoners, it intentionally marooned five men (two Americans and three Brits from the Isabella), who struggled to survive for 534 days in that hostile, unforgiving environment before being rescued themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/1a/0c1a723a-ab67-455d-a31a-9c94177e2682/burning_of_washington_1814.jpeg)

As Charles Barnard, the Nanina’s captain and one of the hapless castaways, later wrote, “To be reduced to this deplorable and almost hopeless state of wretchedness, by the treachery and ingratitude of those for whose relief I had long been laboring, and who, by our unremitted exertions, were raised from the lowest depths of despair … was dreadful in the extreme.”

Excerpted from Left for Dead: Shipwreck, Treachery and Survival at the Edge of the World by Eric Jay Dolin. Copyright © 2024 by Eric Jay Dolin. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/fc/3dfc3579-509c-44da-beb4-48759c1dddd2/isabella.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ericjaydolin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ericjaydolin.png)