Why We Need to Keep Searching for Lost Silent Films

Early motion pictures give us an important window into our collective past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/a0/c2a0d320-8ae7-48f1-a2be-e2746d96e098/00046435.jpg)

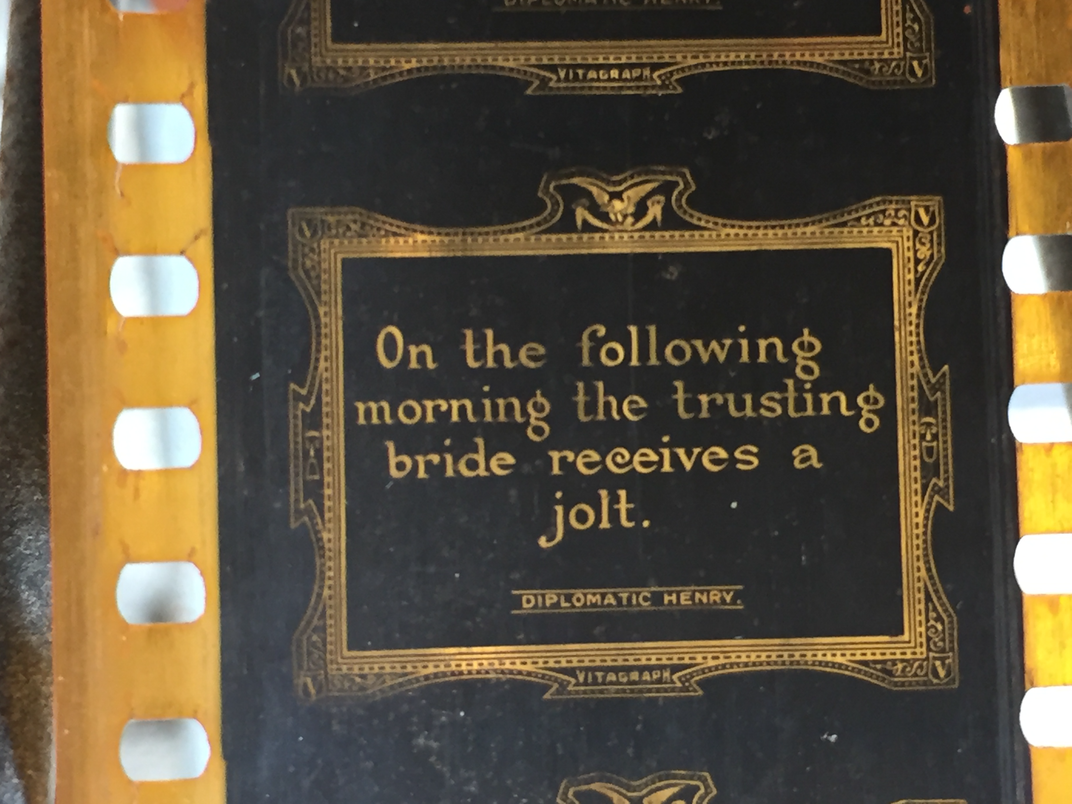

In the summer of 2017, Christopher Bird, a director, editor and longtime film collector, made the ultimate discovery: a complete silent film that had been thought lost forever.

"It’s like having an original Monet painting,” he says of the film, Diplomatic Henry (1915), made by the popular American comedy duo Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew. Partners in every way, the husband-wife pair often shared writing and directing duties. Diplomatic Henry is characteristic of their filmmaking style, which did not rely on slapstick or stunts but instead focused on everyday domestic situations in a May-December marriage with the young wife (Lucille McVey) often seeing through her husband’s schemes and emerging as the victor. This time around, Mr. Drew tries to impress his aunt by implying that his new wife’s homemaking skills are not up to her standards. Instead of battling one another, the women instead team up to teach Drew a lesson he won’t forget.

“Not only does it have a slightly feminist slant, but this film was possibly co-written and directed by its leading lady at a time when women didn’t even have the vote,” says Bird.

Diplomatic Henry is just one of the mere handful of the comedy team’s films that survive to this day. That’s an all-too typical story for silent-era talents. During the silent movie era, roughly from 1895 to 1929, going to the movies became a national pastime with over 10,000 features released by major studios. Audiences drank in the latest fashions, adaptations of fine literature and the new methods of romance, as well as films focused on social justice topics like race, poverty, crime, prostitution and birth control.

Because early motion pictures were released on nitrate film, which is dangerously flammable and susceptible to decay—only to become even more flammable as it deteriorates—the majority of these films are no longer with us today. While the exact number of lost films is unknown, a study commissioned by the Library of Congress ballparks the surviving number at a scant 14 percent.

These lost films have a resonance beyond film history. They might offer historians an opportunity to see historical figures like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or Teddy Roosevelt. They might feature real settings, capturing little moments of history in amber: a detail of fashion, a type of automobile, a shot of a long-gone street. They might help modern viewers better understand how people of the silent era walked and dressed and their views of then-current events and politics. Take the recently discovered silent film Something Good – Negro Kiss (1898), the first known depiction of black people sharing a kiss on film, which New Yorker’s Doreen St. Félix used as a launching point to discuss Barry Jenkins’s new adaptation of James Baldwin’s novel If Beale Street Could Talk.

While films like Something Good—Negro Kiss (which was just inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress) are being rediscovered every year, stories of loss overwhelm the silent film narrative. While fire may be responsible for destroying entire vaults of film history, it does not account for all lost silent films. An enormous number were junked as valueless in the sound era; some were snipped to pieces, others cannibalized for their set pieces that were repurposed for talkies.

When it came to independent films, such as those made by African-American producers, sometimes only a few copies existed because of the prohibitive cost at the time of producing prints. Still other titles were not technically ever lost, they were simply mislaid or mislabeled in an archive or collection. (Take the macabre Lon Chaney vehicle The Unknown (1927)—it was thought to be lost because the title on the film cans was being read as literally “unknown.”)

Most frustrating and tantalizing of all are the films that only partially survive. Fragments, a few seconds, or maybe even entire reels, but not enough to tell the whole story. In her 1980 autobiography, Gloria Swanson issued a plea for the recovery of the missing last reel of Sadie Thompson (1928), for which she received a Best Actress nod at the first Academy Awards. It’s still lost to this day.

Silent film can even help correct the historical record, such as the discovery of Within Our Gates (1920), often cited as Oscar Micheaux’s response to D.W. Griffith’s racist epic The Birth of a Nation (1915).

The Birth of a Nation was not just declared bigoted by the NAACP and other activists when it was first released; it was hotly debated all over the country from courthouses to small-town newspapers, which ran op-eds that declared it “a miscarriage of truth” and "a tissue of falsehoods” designed to glorify the Ku Klux Klan. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation nonetheless proved to be a runaway box-office smash and a critical darling, and was even screened at the White House. The film also emboldened the resurrected Ku Klux Klan—right down to inspiring its infamous pointed hood costume.

Micheaux’s Within Our Gates functions as a powerful counterpoint to Griffith’s version of history. Within Our Gates tackles the popularity of The Birth of a Nation and possibly the Red Summer of 1919 when anti-black riots broke out throughout the U.S., giving voice to the often overshadowed African-American response of the day. Even when it was just described on paper, the film’s powerful story, told in flashbacks about a black schoolteacher and her tragic life in the South, leaps off the page. But after a print was recovered in Spain near the end of the 20th century, the film was finally given the chance to fight fire with fire. Resurrected on the screen, the graphic scenes of an African-American family being hunted down and lynched overwhelm emotionally in a way that stills and descriptions cannot convey. No written account, regardless of its eloquence, could prove as powerful a response to The Birth of a Nation as the film itself.

Yet despite these important finds, even the question of whether silent films are worth preserving has been up for debate since the very first film archives. Do you save everything or just what is considered artistically and historically significant? And who defines what meets those subjective standards?

Henri Langlois, one of several pioneers of film archiving, advocated a philosophy of saving everything and screening as much as he could. During the Nazi occupation of France, he hid banned films and arranged a screening of the forbidden Soviet classic Battleship Potemkin in his mother’s living room.

A controversial figure in the history of film preservation whose methods did not always save films, Langlois nevertheless wanted viewers to be free to decide whether or not a film was good, and there was no way to accomplish that if the film was lost. One generation’s bomb is another’s masterpiece. Who in the 1920s would have predicted that Louise Brooks, while certainly popular at the time, would be considered an iconic figure and one of the greatest actresses of her era some nine decades later?

While not every recovered film is spectacular, the what-ifs are tantalizing. Film historian Lucie Dutton mourns the loss of the original 1918 adaptation of Stanley Houghton’s play Hindle Wakes, not only because of the lost opportunity to see how subject matter of the sexual double standard—that a man is expected to sow some wild oats while a woman must keep herself pure—was handled, but also because director Maurice Elvey received special government permission to shoot on location in the resort town of Blackpool, England. Among other items of interest, Blackpool had set up exact replicas of the trenches in which British soldiers fought in World War I and marketed them as tourist attractions.

Other lost early film versions of books and plays are equally intriguing. You don’t have to be a film buff to mourn the loss of the earliest screen adaptations of Anne of Green Gables (1919), The Great Gatsby (1926) or Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1928).

There is a phrase that silent film fans like to toss around when discussing the tragic topic of lost motion pictures: Keep checking those attics, those basements, those garden rubbish bins as lost films are still out there waiting to be found.

In the case of Diplomatic Henry, Bird found the film while going through the collection of an ailing friend. As it happened, the film collection was stored in a garden trash bin so as not to risk the house going up in flames if the nitrate film ever combusted. “Despite many hot summers, they’d somehow survived,” Bird marvels. (Yes, nitrate truly is that sensitive—during a laboratory test, a roll of nitrate film self-ignited at temperatures as low as 106 degrees Fahrenheit.)

Diplomatic Henry was scanned and restored by Dino Everett at the University of Southern California Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive and made its triumphant reappearance last fall at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, essentially the Cannes festival for early cinema.

The work to get on the screen once again was no easy feat. “It takes an archive a huge amount of time to repair a film print that’s over 100 years old enough to run through a scanner, then to do the relevant necessary restoration work,” Bird says.

According to Everett, the restoration of Diplomatic Henry is still a work in progress. “There is always a thin line between the desire to do the best work possible and the need to exploit modest resources to the limit,” he explained in a programming note for the festival. However, the efforts of archivists like Everett mean that films like Diplomatic Henry can beat the odds and instead of mourning its loss, audiences can gleam something from it once again.

At its festival premiere, Diplomatic Henry, likely unseen since World War I, provided belly laughs once again, the triumphant reemergence of a once-forgotten film made more than 100 years ago.