Will the Search for Amelia Earhart Ever End?

More than eight decades after she disappeared in the South Pacific, the aviator continues to spark intense passion—and controversy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/25/2325f8ab-4afd-4576-9c97-5a4d6b8389fd/dec15_n17_ameliaearhart.jpg)

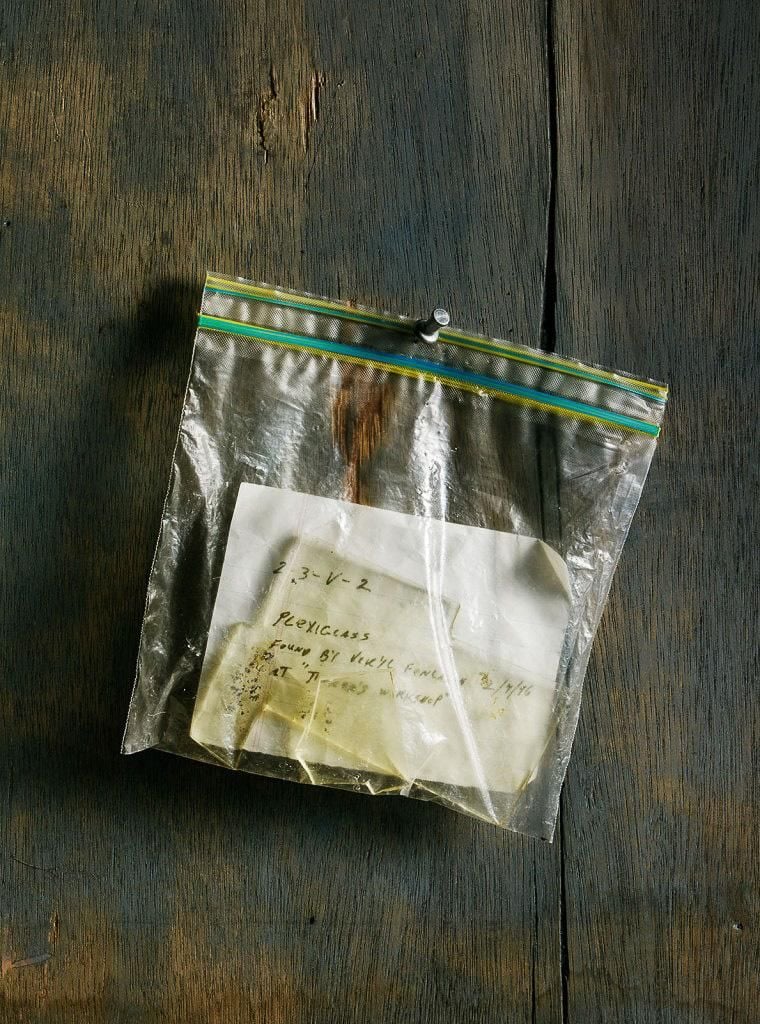

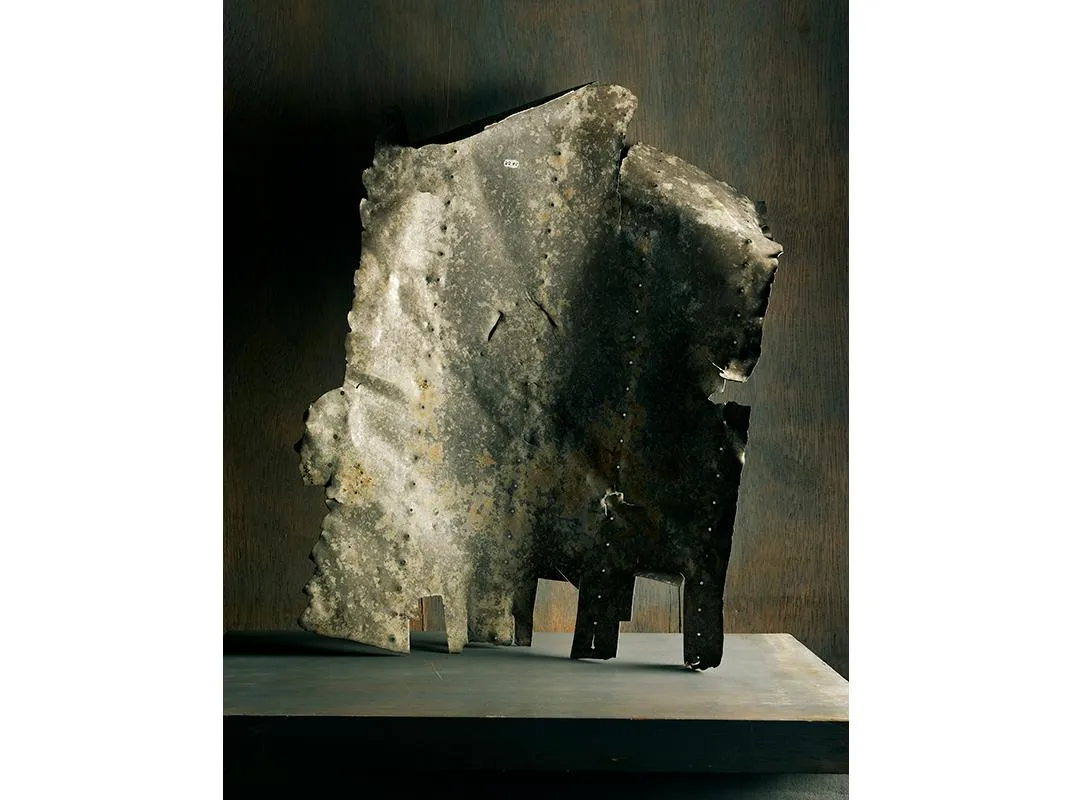

Do you want to see it?” Ric Gillespie asks, reaching for a black portfolio resting on the floor of his Pennsylvania farmhouse. He extracts a sheet of aluminum, about 18 by 24 inches—bent, dented, scratched and crisscrossed by 103 rivet holes, whose size, position and spacing he has studied for almost 25 years the way assassination buffs pore over the Zapruder film. And with good reason: If he’s right, this is one of the great historical artifacts of the 20th century, a piece of the airplane in which Amelia Earhart made her famous last flight over the Pacific Ocean in July 1937.

With rulers, photographs and diagrams, he shows where it could have fit on Earhart’s customized Lockheed Electra, over the hole left when she removed a window on the right rear fuselage. “These things don’t just line up by coincidence,” he says. In late October, after seizing a chance to compare his aluminum sheet against an Electra under restoration in Kansas, he announced that the rivet holes and other features were the equivalent of “a fingerprint” establishing that it had come from Earhart’s plane, leading some news organizations to declare the case closed (Discovery News headline: “Amelia Earhart Plane Fragment Identified”). He tells me he’s “98 percent” sure the piece came from Earhart’s plane. He raises that figure to 99 percent after getting a report from a leading metallurgist, Thomas Eagar of MIT, who concluded that “the preponderance of the evidence indicates you have a true Amelia Earhart artifact.” That’s still 1 percent less certain than he was in 1992, when he told Life magazine: “There’s only one possible conclusion: We found a piece of Amelia Earhart’s aircraft.”

Anyone who thinks his new data will settle the question of what happened to Earhart, though, hasn’t been paying attention for the last 78 years. Other researchers have studied the same rivet holes and radio transcripts and come to radically different conclusions—and they’re not conceding anything.

Ever since Gillespie found this piece of metal in 1991, on the tiny, remote island where he believes Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, crash-landed and died as castaways, he has been the public face of America’s never-ending fascination with Earhart’s fate. Yet it was only in the last few months that he obtained what he considers conclusive evidence that it came from their plane. Rangy and graying, a former pilot and aircraft-accident investigator, he runs, with his wife, an organization called The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery. Since 1989 TIGHAR has mounted ten expeditions to the South Pacific, and he is seeking money for an 11th. His fund-raising prowess and mediagenic announcements have made Gillespie an object of envy and occasional vitriol among his fellow Earhart researchers—a group that includes serious historians as well as wild-eyed obsessives, who pile up scraps of evidence into conspiracies reaching right up to the White House.

“It’s nonstop,” marvels Dorothy Cochrane, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, who was recently contacted by a researcher trying to track down a piece of carved driftwood found 70 years ago that he thinks holds a clue to Earhart’s fate. Cochrane understands the interest in her, but had expected it would have died down by, say, the 1997 centennial of her birth. “That’s what drives me crazy,” she says. “Now that she’s long gone, why are people holding onto this?”

In 1937, Earhart was one of the most famous women in the world, a best-selling author, feminist hero and friend of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Born in Atchison, Kansas, to a locally prominent family, Earhart had fallen in love with flying as a young woman, and she became famous in 1928 as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic—as a passenger, an experience she nevertheless turned into a best-selling book. Subsequently she set numerous records as a pilot, flying solo across the Atlantic, nonstop across North America and from Honolulu to Oakland. With the help of her husband, George (G.P.) Putnam, a scion of the publishing family, she made a career of flying, writing and lecturing. Slender, diffident, good-looking in a tousled way, she reminded people of that other famous aviator from the Midwest, Charles Lindbergh. But, says Cochrane, while Lindbergh shrank from fame, Earhart embraced her opportunity to be a role model for women.

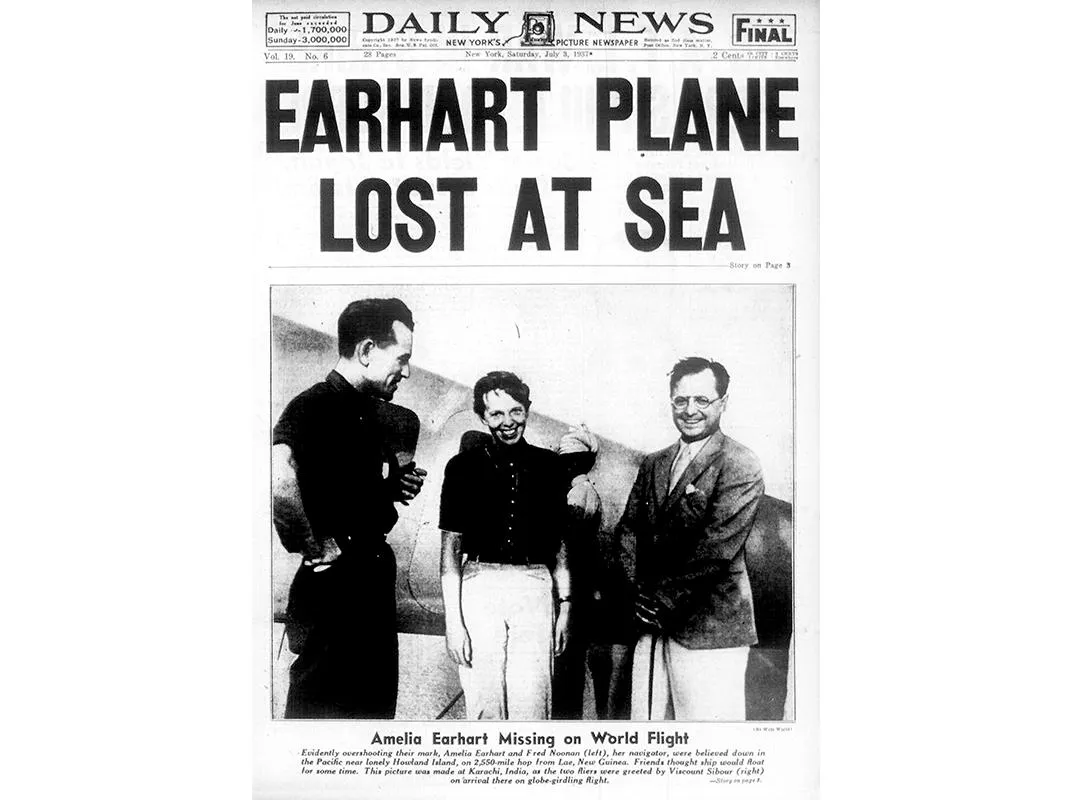

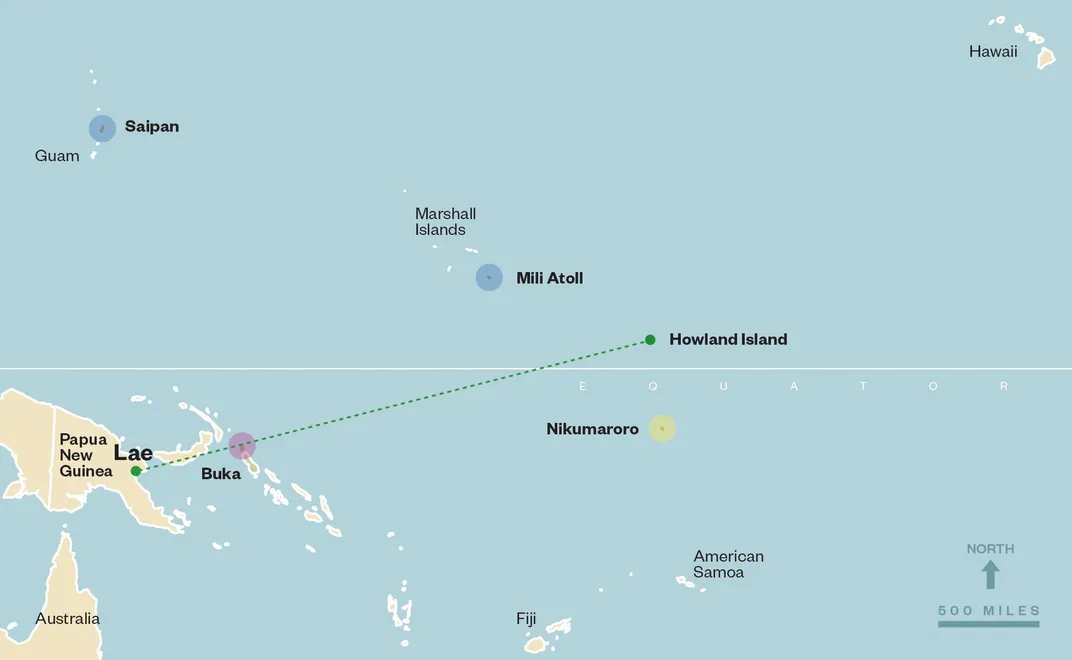

Except by 1937, there were fewer and fewer places left that no one had flown between. Earhart was intent on one last spectacular trip, circling the globe around the Equator on a zigzag route that would cover more than 30,000 miles. In a twin-engine Electra stuffed with enough fuel to stay aloft for 20 hours, she set out that March from Oakland and got as far as Honolulu, where the plane was damaged in a botched takeoff attempt. After it was shipped back to California for repairs, she took off again on May 21, heading east this time, taking 40 days and making more than 20 stops (including Miami; San Juan; Natal, Brazil; Dakar; Khartoum; Calcutta; Bangkok; and Darwin, Australia) to reach the airfield at Lae, Papua New Guinea. The next leg, to tiny Howland Island, 2,556 miles away, would be the hardest. She took off at 10 a.m. on July 2, Lae time, planning to land roughly 20 hours later, on the morning of the same date after crossing the International Date Line. Depending on which version you accept, either she was never seen alive again, or died a few years later in captivity, or lived into her late 70s under an assumed identity as a New Jersey housewife.

***

The world looked very different from inside a cockpit in those days, before radar, GPS or weather satellites. Noonan, a highly regarded pioneer in aerial navigation, had to rely on sun and star “sights” to chart a course. The Electra had a radio direction finder, which could be used to navigate over short distances, but it apparently didn’t work well enough to be helpful. A Coast Guard cutter, the Itasca, was standing by near Howland to guide her in. There was a schedule for Earhart to communicate with the Itasca at specific intervals, but it fell apart, perhaps because the cutter was in an unusual time zone with a half-hour offset. For reasons unknown—Gillespie believes the Electra’s receiving antenna, strung on struts beneath the fuselage, broke during takeoff at Lae—it appears that Earhart never heard the Itasca’s increasingly urgent calls.

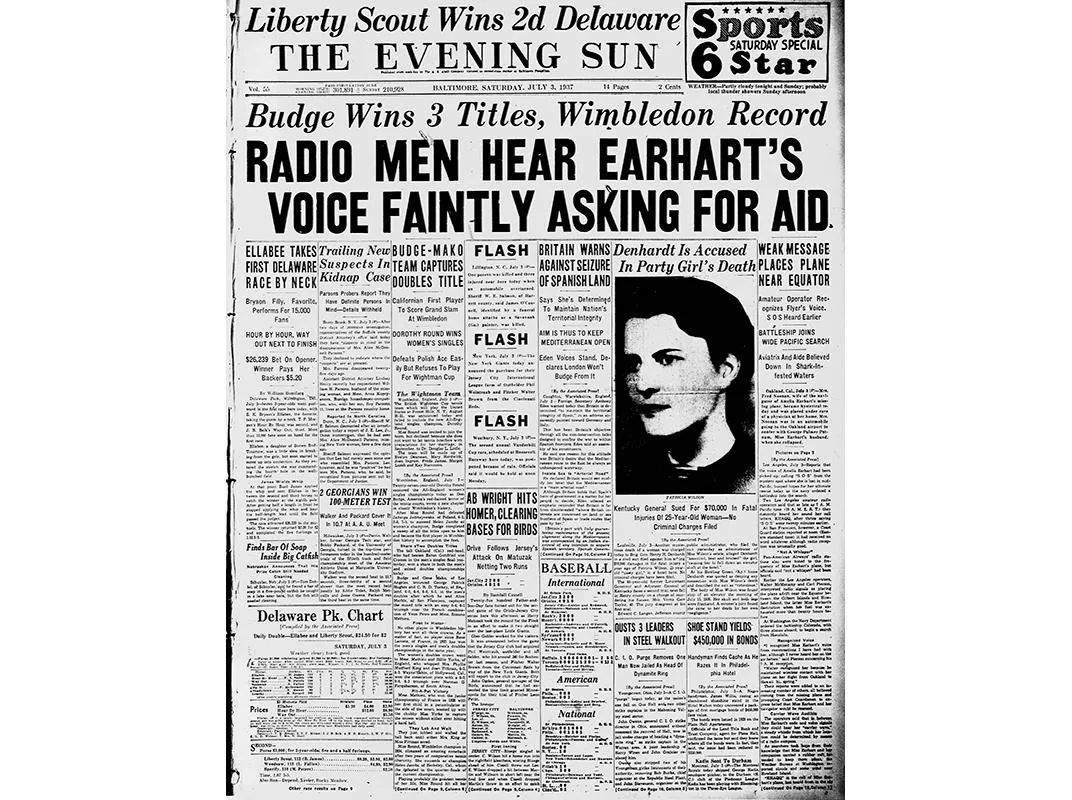

But she must have been close. The Itasca’s operators heard her transmissions, growing stronger as she approached Howland Island shortly after sunrise. At one point her signal was so strong the ship’s radio operator ran to the deck to look for her overhead. But he saw only empty sky, and she, it seems, just clouds and empty ocean. Near the end, her voice was becoming strained; she sounded “frantic,” according to the Itasca’s commanding officer. “We must be on you but cannot see you,” she radioed. “Gas is running low.” Her last message reported she was flying on a line “157” (southeast) and “337” (northwest). But she neglected to say in which of those directions she was heading. After that, silence.

So the simplest explanation, and the official version, of her disappearance: Unsure of her location and out of fuel, she crashed and sank in the 18,000-foot-deep waters northwest of Howland Island. The Itasca hurried off to search in that direction; the battleship Colorado, arriving on July 7, would search to the southeast. The aircraft carrier Lexington, based in San Diego, arrived a few days later and stayed in the area until July 18. None of the ships or planes saw so much as an oil slick. “Crashed-and-sank” was the conclusion of Elgen Long, a veteran military and commercial pilot, who with his wife, Marie, spent 25 years researching their book Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved. It remains the simplest explanation, but for that very reason, has attracted derision from those who prefer their history complicated.

***

Some of the technical points are in dispute. Skeptics point out that the nominal flying time for the Electra on full tanks was 24 hours, not 20. But Earhart had faced head winds of 26.5 miles an hour, roughly twice as strong as forecast. Early in the flight a storm required a fuel-wasting climb to 10,000 feet. In 1999, an analysis by Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Center concluded that her tanks were almost certainly empty as she approached Howland. “She probably should have turned back to Lae at the halfway point,” says David Jourdan, the president of Nauticos, an undersea exploration company, which has sent two expeditions to look for the wreckage. “She knew she was going in,” Long says. “She couldn’t find the island and was running out of fuel. Her voice showed that.”

Others come to different conclusions. Gardner Island (now Nikumaroro, part of the Republic of Kirabati), where Gillespie has been searching, is about 350 nautical miles from Howland—coincidentally, or not, along the “157-337” line Earhart said she was flying—so he has tried to show she had enough fuel to fly at least that far. He also cites dozens of messages, supposedly from Earhart, that were heard around the Pacific and as far away as Florida for five days after she disappeared. (Under certain conditions, shortwave radio waves, reflected by the ionosphere, can “skip” for thousands of miles.) Obviously, if genuine, these would disprove the crashed-and-sank theory. Some clearly were hoaxes, but others are harder to dismiss.

Betty Klenck, a teenager in St. Petersburg, Florida, was cruising the dial on her family’s shortwave set and was startled by a voice saying, “This is Amelia Earhart. Help me!” Sitting alone in her family’s living room, she strained to hear a woman crying, calling for help and arguing with a man who seemed to be delirious. “Waters knee deep!” Betty heard. “Let me out!” As the weak signal faded in and out over three hours, Betty copied what she heard into her notebook. Her father reported it to local Coast Guard officials, who told him everything was under control. Betty held on to the notebook until she showed it to Gillespie in 2000.

Gillespie believes that, after an emergency landing on the reef—the only feasible landing spot—at Gardner Island, Earhart broadcast from the plane for at least the next five nights, running the engines to charge the radio batteries. He plotted the times when people reported hearing Earhart against the local tides, and showed that the broadcasts stopped at high tide, when water would have reached the propeller, making it impossible to run the engine.

One problem with his theory is that Navy planes searched the four-mile-long Gardner Island on July 9 without seeing Earhart. It would seem uncharacteristically careless of Earhart and Noonan not to keep a watch out for rescuers. And where was the Electra? Gillespie has to argue that sometime between July 7 and 9, a storm blew it off the reef to the deep water beyond, fortuitously leaving behind one piece to be found by him more than 50 years later. If so, the plane would still be there. Gillespie intends to find it.

In his ten trips to Nikumaroro, Gillespie has brought back a rusted pocket knife, bottles, zippers and pieces of a shoe, any of which could have belonged to Earhart and Noonan, but also to the people who lived on the island between 1939 and 1963. Gillespie and Elgen Long have been arguing for decades over the piece of aluminum found there. Long says the piece obviously comes from the wing of a PBY, a U.S. military seaplane. “I think if Ric proved anything, it’s that [Earhart and Noonan] never were close to that island,” says Tom Crouch, senior curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum. “Otherwise he would have found something definitive. Ric is in the business of taking wealthy people on an archaeological adventure, Indiana Jones-style.”

***

Of course, nobody else has found a plane, either. Nauticos calculated where the Electra most likely sank, outlining an area of 1,800 square miles north and west of Howland. More than three-quarters of it has been searched by towed submersibles mapping the seafloor with sonar, without finding anything like an airplane fuselage.

But others have other ideas of where to look. One is Bill Snavely, a Maryland social worker who says he’s “always gotten interested in mysteries.” He started looking into the Earhart disappearance a decade ago, concentrating on the first two-thirds of her final flight, which searchers have largely overlooked. He flew to Rabaul, a city in Papua New Guinea about 360 miles east of Lae. Like so many stories in the Earhart canon, Snavely’s hinges on a chance encounter, in his case sharing a taxi with a New Guinea corrections officer, who, learning of Snavely’s quest, said, “I know where there’s a plane.”

The plane is in 100 feet of water, off a beach near Buka Island, just off Bougainville. It is mostly buried in sediment, but divers report seeing at least one body inside, Snavely says, and a suitcase with the initials “GP”—those of Earhart’s husband. An old man from the island recalled, as a boy, seeing a plane with its engine on fire landing right at the waterline one morning, and floating near the beach for over an hour. A man and woman were in the plane, but he didn’t see what happened to them. Snavely’s account, which he has kept secret for nine years, is to be featured in a two-hour documentary inaugurating a new series on the Travel Channel, “Expedition Unknown,” airing January 8. The show also explores the possibility (to put it generously) that some bones the host, Josh Gates, dug up under a house in Fiji were Earhart’s remains.

Snavely’s task is to explain what the Electra was doing near Buka, almost 2,000 miles west of where it was supposed to be. For this he turns to one of the more esoteric books on the Earhart saga, Amelia Earhart’s Radio, by Paul Rafford Jr., a retired Pan Am navigator who believes she never intended to land at Howland. Her radio transmissions could have been “recorded well beforehand by a sound-alike actress” and played back to the Itasca from hidden transmitters. (The “frantic” tone of her last messages might have been caused by playing the tape back at the wrong speed.) Snavely believes Earhart headed for a secret airstrip somewhere in the Pacific, turned around well short of Howland, and crashed near Buka when an engine caught fire.

And why would they deviate from the route to Howland? Well, given rising tensions in the Pacific, the Navy might have wanted better maps than the century-old ones it was using. By disappearing, Earhart would give the Navy an excuse to search the area without arousing suspicion. If Rafford had proof of this plot, he didn’t put it in his book. He mentions a phone call in 1938 between Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau and Malvina Thompson, Eleanor Roosevelt’s secretary. Roosevelt had asked about the fate of her friend Earhart; Morgenthau, who oversaw the Coast Guard, had read the classified report by the Itasca’s captain, which essentially blamed Earhart for getting lost, and was trying to keep it secret. “Amelia Earhart absolutely disregarded all orders,” he quotes Morgenthau as saying. The full transcript of the call, which has been declassified, continues, “and if we ever release this thing, goodbye Amelia Earhart’s reputation.” Rafford puts a conspiratorial twist on “disregarded all orders.” But an alternative reading is that Earhart simply didn’t follow the Itasca’s instructions as the crew tried to get a radio fix on her plane. As we know today, she probably never heard them.

Also, if that was the plan, the Navy seemed unprepared on its end. The additional ships and planes it would use in the search were in far-off Hawaii and San Diego. Was this plot necessary? Rafford’s scenario is reminiscent of a different plot: the plot of the 1943 movie Flight for Freedom, in which a famous female flier (played by Rosalind Russell) flying around the world is recruited to secretly spy on islands in the Pacific. Spoiler alert: She doesn’t return.

Japan looms large in Earhart research. In July 1944, Army Sgt. Thomas E. Devine arrived on the just-liberated island of Saipan. At the airfield, he met some Marines guarding a closed hangar they said contained Earhart’s plane. Later, he said, he saw the Electra take off and fly around the island—and, that night, destroyed by U.S. soldiers. After the war, Devine plunged into Earhart research, returning to Saipan to pursue his theory that Earhart and Noonan flew there by mistake, were captured, imprisoned and executed as spies.

Devine’s riveting account, which he shared with fellow researchers at least as far back as the 1960s, has been taken up by others, although his assertion that she flew for almost an entire day in the wrong direction hasn’t won many adherents. The capture theory exists in innumerable variations, including one advanced in the 1960s by CBS newsman Fred Goerner, who claimed that Earhart had been following secret instructions to overfly and observe the key fortifications at Truk. In its most fevered incarnation, Earhart survived the war, was repatriated and lived out her life under the assumed identity of a New Jersey woman named Irene Bolam. At least three books were written on this premise. The justifiably annoyed Bolam sued the publisher of one and it was withdrawn, but is now available again. Bolam died in 1982. The idea lives on.

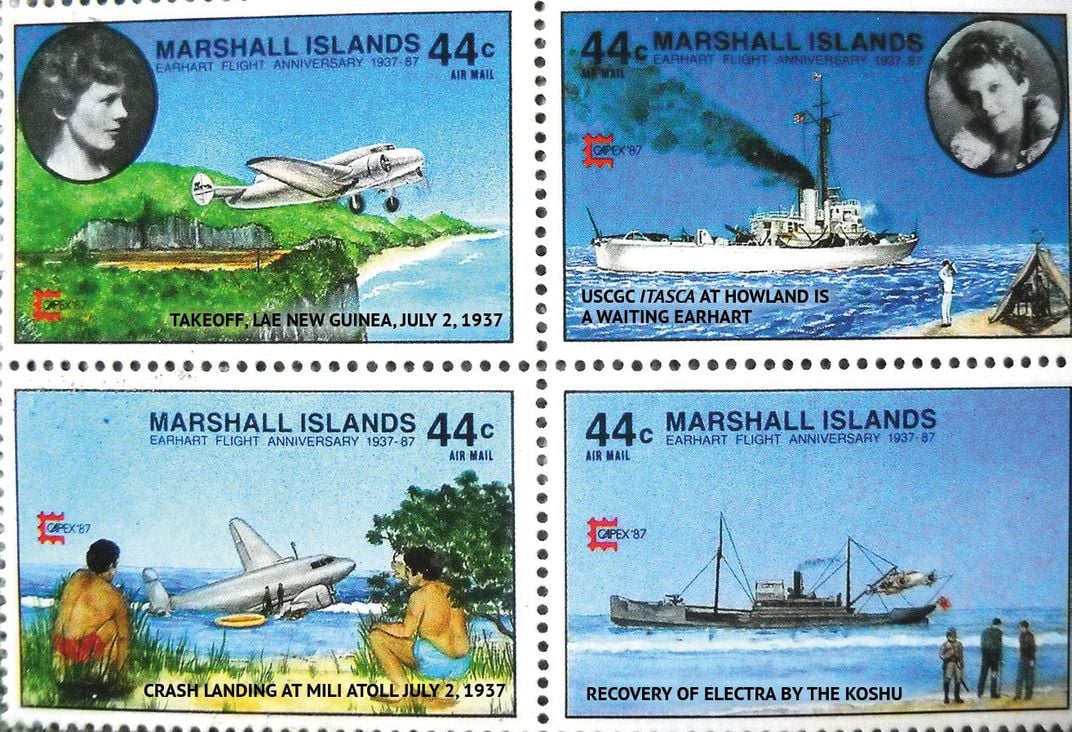

The mainstream capture account holds that the fliers, after failing to make landfall at Howland, turned northwest and came down 760 miles away in the Japanese-held Marshall Islands, probably Mili Atoll—an event that apparently is taken as fact in the Marshalls itself, which in 1987 issued a plate block of stamps depicting her flight, including a crash landing on the atoll. From Mili, the fliers and their plane were taken by ship to Saipan, where “imprisonment, possible torture and misery were their daily companions, until death mercifully released the ill-fated pair from their torments.” That part is from Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last, by Mike Campbell, an especially dogged Earhart researcher who collaborated with Devine on an earlier book.

Campbell has amassed a mountain of testimony from American servicemen and Pacific Islanders to show that an American man and woman landed in the Marshalls in 1937 and were taken to Saipan, although apparently they never introduced themselves by name. To his credit, he concedes that not all of it is credible, and some is contradictory—Earhart was executed by some accounts, died of dysentery in others. His book is filled with mysterious disappearances, cryptic warnings from sinister strangers and suspicious deaths. Much of Campbell’s evidence is second- or third-hand. He quotes a remark by the venerated Adm. Chester Nimitz, for which the only source is Fred Goerner—“I want to tell you Earhart and her navigator did go down in the Marshalls and were picked up by the Japanese”—and a handwritten letter from Marine commandant Alexander Vandegrift, passing along the judgment of one of his generals—“...it had been substantiated that Miss Earhart met her death in Saipan.” Campbell gives great weight to one line of hearsay from a 1960 report by the Office of Naval Intelligence, claiming that Earhart “may possibly have been brought to Saipan by the Japanese military,” but dismisses the rest of the report as a mendacious government whitewash. Still, it’s possible to come away thinking Campbell is on to something.

If you don’t, Campbell is ready with an explanation: You have bought into a conspiracy of silence imposed by the government and enforced by a cynical, lazy media, to protect the reputation of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He believes FDR knew Earhart was on Saipan but didn’t want to risk a confrontation with Japan, so colluded in keeping it secret. “Roosevelt,” Campbell writes in an email to me, “could never have survived public knowledge that he failed to help America’s No. 1 aviatrix of the Golden Age of Aviation....The truth is not a matter of opinion.”

So: the truth at last? What struck me, as I was researching this story, is how each of the major theories comes with its own explanation of why people don’t want to believe it. Campbell sees a government conspiracy. The Smithsonian’s Tom Crouch thinks the official version is too straightforward to meet the public’s emotional need for mystery and intrigue. Gillespie says the public doesn’t want to think of Amelia dying on Nikumaroro, a brutally hot place inhabited by foot-long centipedes and giant carnivorous crabs. “A nice clean death at sea,” he muses, “is preferable to being eaten alive by crabs.” In Earhart’s fate, we see a reflection of our own deepest fears—the laughing, carefree young woman taking off on a grand adventure, and never coming back.

Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last