Without Chick Parsons, General MacArthur May Never Have Made His Famed Return to the Philippines

The full story of the American ex-pat’s daring feats has not been told—until now

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/a9/efa9f6c1-8692-4e07-bc8d-bfcdea26358a/sep2017_a08_parsons-wr.jpg)

Chick Parsons needed sleep. He’d been hack-ing through jungles by day and island-hopping by night for almost four months. His mission in the Philippines—assigned by Gen. Douglas MacArthur himself—was to contact soldiers who had taken to the hills when the Japanese Army defeated the United States on Bataan and Corregidor in the spring of 1942. These scattered fighters, both American and Filipino, had been trying to organize themselves into a guerrilla force that could harass the occupiers throughout the 7,000-plus islands of the Philippine archipelago. They desperately needed medicine, weapons, ammunition and radio gear, and on a clandestine mission in the spring of 1943, Parsons delivered it.

More important, he offered an early sign that MacArthur would make good on the vow he’d issued after retreating from the Philippines. The general was still in his headquarters in Brisbane, Australia, 3,000 miles away, but to the unorganized and information-starved men in the jungle, the presence of his personal envoy whispered: I shall return. “The effect upon the guerrillas (also upon the civilians) was miraculous,” Parsons wrote in a letter to the Philippine president-in-exile, Manuel L. Quezón. “It was touching to observe the gratitude of the men for the supplies. It showed them they were not abandoned, that their efforts were known to and appreciated by General MacArthur—it gave them new life.”

Before World War II, Parsons had been the toast of Manila society, successful in business and unrivaled on the polo field, a gregarious, muscular expat American with a shock of wavy brown hair, a winning smile and an eagle tattooed across the expanse of his chest. Now, he needed respite and time to organize the intelligence he’d amassed in the field. He had ten days to burn before his rendezvous with a submarine that would take him back to MacArthur’s headquarters, so he sought safety in the port town of Jimenez, on the island of Mindanao. One of his many friends, Senator José Ozámiz, had a manor house there, and Parsons set himself up in a second-story room. Between naps, he began writing a voluminously detailed report for MacArthur: guerrilla leaders’ names and abilities; their men’s health and morale; plans for equipping them to track and report Japanese ship movements; where and how to build a bomber base.

The afternoon of Saturday, June 26, was typically steamy, but a breeze off Iligan Bay blew across Parsons’ high-ceilinged room. He was still there at dusk when one of the senator’s daughters stopped by with a warning: A Japanese patrol was near. But there had been a series of false alarms recently, and besides, the Ozámiz house, like many others in Jimenez, had been boarded up on the first floor so it would seem abandoned. Parsons stayed put.

Some time later, he heard an engine idling and a vehicle door thrown open, followed by footfall on the pavement below. At that point, few Filipinos were allowed gasoline or permits to drive. They rode horses, drove ox-drawn carts or walked on their bare feet. Not so the occupying army. “The guerrillas knew—we learned, all of us learned—that they always wore boots, complete equipment,” Parsons recalled years later. “So when you were going down a trail at night and you could hear somebody coming on the trail the other direction, if they were wearing shoes, you knew damn well they were Japanese.”

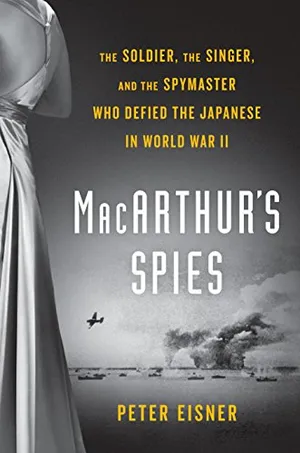

MacArthur's Spies: The Soldier, the Singer, and the Spymaster Who Defied the Japanese in World War II

A thrilling story of espionage, daring and deception set in the exotic landscape of occupied Manila during World War II.

He had surveyed escape routes as soon as he arrived at the house, according to an account provided by his son Peter. Now, he jumped from his bed, scooped his papers into a shoulder bag and peered down from the corner of a window in his room. Soldiers were circling the house. As they started banging on the boards covering the front door, he bolted downstairs to the darkened archways of the parlor, then toward the kitchen at the back of the house, then out the back door. A pig ambled and snorted nearby, nose to the ground. Parsons vaulted down the steps and past the water well. A soldier spotted him, but not in time to shoot. All he saw was a nearly naked man, with wild hair and beard, bounding over a low concrete wall.

**********

Even before his mission to Mindanao, Chick Parsons had had an eventful war: In the chaotic early days of the Japanese occupation, he remained in Manila with his family to spy for the Americans, and he kept his cover even after he was detained, beaten and almost certainly tortured. After he was released, he brought his family to the United States—and soon heeded a summons from MacArthur to get back into the war. By 1944, he was preparing the way for the Allies’ victory in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which many historians consider the biggest naval engagement in history.

“He is the main organizer of the resistance movement on the ground,” James Zobel, the archivist at the MacArthur Memorial Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, told me. “He knows all the people, gets them set up in all the military districts and gets them to understand: ‘Unless you follow the rules that MacArthur has laid down, we’re not going to support you.’ It would be hard to imagine anyone other than Parsons accomplishing this. Headquarters has a paper idea of how things should go, but he’s the guy who really gets it implemented.”

And yet Chick Parsons’ name barely registers in accounts of the Pacific war. A few years afterward, he collaborated with a writer, Travis Ingham, on a memoir, Rendezvous by Submarine. While some passages shift into the first person, he shied away from self-aggrandizement. “I am not a colorful figure,” he wrote in a letter to Ingham, “and I wish to be kept out of the story of the guerrilla movement as much as possible.” His modesty may be one reason that the book was never widely read.

I first learned about him while researching the life of another American expatriate caught up in the Philippines’ wartime intrigue, Claire Phillips. A singer and hostess, she wrangled intelligence from Japanese officers who frequented a nightclub she set up in Manila. Phillips’ wartime diary, which I discovered among about 2,000 documents pertaining to her and her allies at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., includes cryptic entries for June 30 and July 3, 1943: “Will be busy for next four days...S. Wilson and Chick Parsons arrived. Must get all to them.” (Parsons and Sam Wilson, an American friend turned guerrilla, were in the vicinity of the capital.) My research ultimately led to my book MacArthur’s Spies, which focuses on Phillips and includes Parsons and the American guerrilla John Boone in supporting roles.

As I wrote it, I came to laugh at Parsons’ self-assessment—“not a colorful figure”—and to feel that his wish to be kept out of the story was too modest by half. Accounts of his World War II service lie fragmented in the reports he filed, records kept by military commanders in the Pacific and documents in the MacArthur Memorial Museum archives. Those records, plus interviews with his son Peter and an unpublished oral history Parsons gave in 1981, help clarify one of the most vital yet shadowy stories of the Pacific war.

**********

Charles Thomas Parsons Jr. was born in 1900 in Shelbyville, Tennessee, but his family moved frequently to avoid creditors. When young Charles was 5, his mother sent him to Manila for a more stable life with her brother, a public health official in the American-run government. The boy received his elementary education speaking Spanish at the Santa Potenciana School, a Catholic school founded in the 16th century. Parsons’ nickname, “Chick,” was perhaps shortened from chico, for “boy.” While he loved his childhood in colonial Manila, Parsons confessed late in life to his son that he never really got over the pain of being sent away. “It hurt him a lot,” Peter Parsons told me. “He asked me, ‘Can you imagine how I felt?’”

He returned to Tennessee as a teenager and graduated from Chattanooga High School. He sailed back to the Philippines as a merchant marine seaman in the early 1920s and shortly got himself hired as a stenographer for Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, a hero of the Spanish-American War (he commanded the Rough Riders beside Theodore Roosevelt), who was then serving as the U.S. governor general of the Philippines.

Parsons traveled throughout the country with Wood; learned Tagalog, the basis for the national language, Filipino, and made friends and visited places beyond the reach of most travelers. Unlike other Americans, he went beyond the society of the colonial elite and formed enduring friendships with Filipinos. In 1924, he parlayed his contacts into a job as a lumber buyer with a California-based logging firm, traveling to make export deals and extending his knowledge of the islands and his array of friends. While working in Zamboanga, on Mindanao, he met Katrushka “Katsy” Jurika; her father was an émigré from Austria-Hungary who owned a coconut plantation and her mother had come from California. Chick and Katsy married in 1928. He was 28, she 16.

The Wall Street crash of 1929 doomed the logging firm, but the next year Parsons became the general manager of the Luzon Stevedoring Co., which exported manganese, chrome, coconuts, rice and other commodities to several countries, including Japan. Chick and Katsy moved to Manila, and he joined the U.S. Navy reserve in 1932, receiving a commission as a lieutenant, junior grade. Their social circle included Jean and Douglas MacArthur, then commandant of the Philippine Commonwealth Army, and Mamie and Lt. Col. Dwight David Eisenhower.

Through 1940 and ’41, as economic tensions between the United States and Japan surged, Parsons labored to protect his company’s dwindling export options. Those options ran out on December 8, 1941 (December 7 in the United States), when news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reached Manila. Before sunrise that day, Adm. Thomas C. Hart, commander of the Pacific Fleet, summoned Parsons to his office and swore him in as an active-duty officer, assigned to naval intelligence in Manila’s port.

Within hours, Japanese bombers destroyed most of the U.S. Army Air Force stationed in the Philippines while its planes were still on the ground. In the following days, Japanese sorties rained ordnance on the port. All Parsons could do was tend to the wounded and carry away the dead. As Japan obliterated U.S. defenses, MacArthur ordered his forces in Manila to retreat to Bataan and Corregidor on Christmas Eve. Parsons stayed behind to supervise a skeleton crew assigned to scuttle ships and destroy other materiel to keep it out of enemy hands. On January 2, 1942, the Japanese Army marched into Manila unopposed.

Parsons retreated—only so far as his house on Dewey Boulevard, where he burned his uniforms and any other evidence that he was a United States Navy officer. But he held on to his Panamanian flag. Because of his experience in shipping and port operations, Panama’s foreign minister had named him the country’s honorary consul general to the Philippines. While the occupation authorities ordered that the 4,000 Americans in Manila be detained at the University of Santo Tomas, they left Parsons, his wife and their three children alone, believing he was a diplomat from Panama, a neutral country.

For the next four months, speaking only Spanish in public and flashing his diplomatic credentials whenever necessary, Parsons collected strategic information, including Japanese troop strengths and the names and locations of American prisoners of war. He also began to organize friends in Manila and beyond for an eventual underground intelligence network that would range through all of Luzon, the largest and most populous Philippine island. But his time ran out after Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle led a 16-plane bombing run on Tokyo on April 18. The raid left 87 people dead, most of them civilians, and 450 wounded, including 151 serious civilian injuries.

In Manila, the Japanese Army’s feared Kempeitai military police retaliated by rounding up all non-Asian men—including Parsons, diplomatic immunity be damned. They were thrown into a stone dungeon at Fort Santiago, the 350-year-old fortress within Intramuros, the colonial walled city where Chick had lived and played as a child. Prisoners there were routinely beaten with wooden bats, tortured with electric wires and waterboarded. “They pushed me around a little bit, didn’t amount to very much, but it was painful,” Parsons recalled in 1981. Chinese diplomats in an adjoining cell, he said, had it far worse—and one day “they were all marched out of the cell and...beheaded.”

Under interrogation, Parsons admitted nothing. “I had done so many things,” he recalled. “...If I’d admitted to one, they might have taken me out and hung me.” After five days of grilling, Japanese guards sent him without explanation to the civilian detention center at the University of Santo Tomas. Lobbying by other diplomats got him released, and he was taken to a hospital, suffering from unspecified kidney problems—one possible consequence of taking in too much water, as waterboarding victims often do.

Still, the Japanese believed Parsons was Panama’s consul general to Manila, and they allowed him and his family to leave the Philippines in June 1942 in an exchange of diplomatic detainees. In a daring parting gesture, he and Katsy smuggled out documents they had gathered in a diaper bag they carried for their infant son, Patrick.

By the time the Parsons family reached New York on August 27, the Navy had lost track of Chick—he was listed as missing in action. But he reported for duty within days and settled in at the War Department in Washington, D.C., to write a review of his six months in occupied territory.

Late that fall, MacArthur began receiving intermittent radio messages from the guerrillas in the Philippines, declaring they were ready to fight. He had no way of assessing the communications, or even guaranteeing it wasn’t Japanese disinformation. Then the general received word from the Philippines government in exile that his old friend wasn’t missing in action. He cabled Washington: “SEND PARSONS IMMEDIATELY.”

**********

The two were reunited in mid-January 1943 at the U.S. Southwest Pacific Area headquarters in Brisbane. In MacArthur’s office, Parsons recalled, “The first thing he asked was, ‘Would you volunteer to go back to the Philippines?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘You know you don’t have to. You know this is purely a voluntary deal.’” Then he added: “I do need you badly.” Parsons was assigned to the Allied Intelligence Bureau, but MacArthur broke the chain of command and dealt with him directly.

Within a month, Parsons was on a submarine bound for Mindanao. “I don’t want you to be silly about doing anything that would jeopardize your life or get you into the hands of the enemy,” MacArthur had told him before he boarded.

Over Parsons’ months of island-hopping and jungle-trekking, he did what he was told, gauging the guerrillas’ strength, establishing reliable communications and laying down MacArthur’s rules. Guerrilla leaders had been jockeying for rank and power, with some even calling themselves “general.” No more. They were now under the direct command of the U.S. Army, and there was only one general, MacArthur, and he ordered them to avoid taking the offensive against the Japanese for the time being. The guerrillas weren’t yet strong enough, and any attacks by them could bring reprisals against civilians. As he did so, Parsons managed to unite disparate Filipino Muslim guerrillas with Christian fighters in a common effort against the Japanese.

There is strong anecdotal evidence that he took a potentially lethal side trip to Manila.

That May, Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo marched triumphantly through the capital’s streets on his first foreign visit of the war. As the occupation authorities pressed Filipino leaders to serve in a puppet government, they were tightening their hold on the city. It would have been brazen, to say the least, for an American spy to enter, but at least half a dozen people reported after the war that they saw Parsons in Manila that spring.

John Rocha, who was 5 at the time, recalled that a man on a bicycle stopped to give him magazines and candy. “That was Chick Parsons,” Rocha’s father told him. “Do not mention that you saw him.” A bartender at Claire Phillips’ nightclub, Mamerto Geronimo, said he met Parsons on the street, dressed as a priest. Peter Parsons once overheard his father telling a friend, “I really looked the part. I even had the beard. I looked like a Spanish priest.” A Japanese officer said he realized in retrospect that Parsons had used the same disguise to visit his friend Gen. Manuel Roxas—while the general was under surveillance.

Such a visit would have been operationally useful. Roxas was one of the most respected leaders in the Philippines, and although he eventually agreed to serve in the puppet government, he secretly passed information to the guerrillas. But Parsons also would have had a second, entirely personal motive for sneaking into Manila: his mother-in-law, Blanche Jurika. She had refused to leave with the Parsons family so she could remain close to her son Tom, who was fighting with the guerrillas on Cebu and Leyte islands. In Mamerto Geronimo’s recollection, Parsons, in his clerical disguise, was walking down a street close to the monastery where she was staying.

Parsons never spoke publicly about his whereabouts at that time. In his report to MacArthur—which he finished in a jungle hide-out in the foothills below Mount Malindang, after eluding the Japanese soldiers at the Ozámiz house on Mindanao—he wrote that he had made contact with Roxas, but didn’t say exactly how.

Even that was enough to bring down the wrath of the officers on MacArthur’s staff, who felt Parsons had gone beyond his mission. MacArthur “is amazed at the news...that Parsons has established communication with Roxas without reporting the fact to General Headquarters,” Maj. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, the commander’s chief of staff, wrote in an angry letter to Lt. Col. Courtney Whitney, Philippines chief at the Allied Intelligence Bureau. “That he has a private agent in Manila and that he has apparently established a private code with Roxas. The Commander-in-Chief desires full information with reference to this matter.”

In response, Parsons made no apologies, and didn’t directly deny that he had gone to Manila. He just replied, “My only communication with Roxas was thru trusted agents, and was limited to the time I was in Mindanao.” He added that he had tried to keep headquarters in the loop about attempts to rescue Roxas from the Japanese. “This matter was duly advised...by radio...and instructions were requested,” he wrote. “None being received, I sent word to General Roxas telling him to await the pleasure of General MacArthur.” That, he added, was the only reason for using “a secure method by which any message from General MacArthur could reach General Roxas safely and without placing him in jeopardy.”

In the end, Parsons paid no penalty. His report ended with the recommendation that he be sent back to the Philippines as soon as possible. MacArthur took him up on it.

**********

On November 11, 1943, Parsons was aboard another submarine, the USS Narwhal, on his way to the Philippines for his second mission. The sub was two weeks out of Brisbane when its skipper, Cmdr. Frank Latta, spotted a Japanese oil tanker. As Latta cleared the bridge to fire, a convoy of Japanese support vessels appeared on the horizon. The sub fired four torpedoes but missed. The warships gave chase. “We ran into a real hornets’ nest,” Parsons wrote in a subsequent report. The sub was pinned in close to shore as destroyers and other ships dropped depth charges. “We surfaced to get away and were chased into what looked like a blind alley,” Robert Griffiths, an officer aboard the Narwhal, said in a postwar account. “When we asked Chick Parsons if he recognized the surrounding mountain peaks, he said, ‘Yes, keep going straight ahead.’”

They escaped at emergency speed through a strait between islands and coastline, under fire. In his report, Parsons gave a minimalist summary of the “hornet’s nest”: “Delayed one day due to unexpected enemy interference.” He arrived on Mindanao “without difficulty.”

On this second trip, he delivered tons more food and medicine and weaponry, along with additional radio transmitters to extend a network of coastal watch stations. He also brought in millions of dollars’ worth of counterfeit pesos, not only to enable the guerrillas to buy supplies when they were available, but also to destabilize the Philippines economy. Through the end of the year, he circulated among guerrilla encampments on Mindanao and beyond. “Some of the islands were swinging beautifully into line under strong individual leaders,” he reported. “Tens of thousands of American and Filipino guerrillas were prepared to rise up, greet and support the general’s return to the Philippines.”

When Parsons returned to Brisbane, he told MacArthur that he should keep going with the submarine resupply operation, and the general agreed. Before the war was over, the operation, known as Spyron (for “Spy Squadron”), carried out 41 more missions, landing in practically every part of the Philippines and taking advantage of Parsons’ contacts to keep the guerrillas fed, armed and organized. It also ferried more than 400 American and foreign nationals to safety.

By February 1944, when Parsons infiltrated the Philippines for the third time, he could report to MacArthur that guerrillas were ready and civilians were aching for a U.S. invasion. And by June, the tide of war had turned in the Allies’ favor. After destroying 500 Japanese planes and three aircraft carriers in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, U.S. forces took the Mariana Islands, including Guam, slicing Japanese supply lines. In September, they moved on to Morotai and Palau, less than 500 miles from Mindanao. Open water lay ahead toward the Philippines.

The next month, the U.S. Pacific and Southwest Pacific Commands began assembling a force of 300 ships and 1,500 airplanes for an attack on Leyte Island, between Mindanao and Luzon. Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, commander of the Sixth Army, assigned Parsons to infiltrate the island beforehand, prepare the local guerrillas and move civilians out of harm’s way—all without giving away the attack plan. Krueger warned: “This is one time you definitely must not be captured.”

**********

On the afternoon of October 12, 1944, a Catalina “Black Cat” flying boat belly-flopped onto the blue-green waters of Leyte Gulf about 40 miles south of Tacloban, the island capital. As its engines churned, someone tossed an inflatable raft from the plane. Parsons lowered himself in, along with Lt. Col. Frank Rawolle of Sixth Army Special Intelligence, and they started paddling to shore as the plane taxied away and returned to its base in New Guinea.

Over the next four nights, he sent coded messages about enemy positions to headquarters, and warned guerrilla leaders and civilians to pull back from the shore, without precisely revealing the impending attack’s timing or targets. After four nights, U.S. bombers began hitting Japanese installations, including those he and the guerrillas had targeted. He stayed with the guerrilla commander, Col. Ruperto Kangleon, and his men, mapping out further attacks.

The Navy launched the main invasion attack at 10 a.m. on October 20. When U.S. forces landed that morning, “they encountered light opposition,” recalled Fleet Adm. William F. Halsey Jr.; there was considerable ground fire, but the Japanese warships were elsewhere. By the time a second assault wave landed, an hour later, the Americans were moving toward Tacloban. And a third wave, at midday, included MacArthur himself. Accompanied by aides and a committee of Filipinos, he stepped up to a mobile microphone even as the battle raged and declared, “People of the Philippines, I have returned.”

Parsons, meanwhile, introduced Kangleon to General Krueger, and the guerrillas joined the invading U.S. Army, elated to be on the offensive at last. As they fought on the ground, three Japanese naval fleets of some 67 warships arrived on October 23—and met some 300 ships from the U.S. Third and Seventh fleets. Over the next three days, the Battle of Leyte Gulf played out in four separate engagements, during which the U.S. suffered some 3,000 casualties and lost six ships. The Japanese fleet, however, was vitiated: 12,000 casualties and 26 ships sunk, with others irreparably damaged. The defeat virtually wiped out the empire’s capacity for both fighting at sea and moving supplies. “All of your elements—ground, naval, and air—have alike covered themselves with glory,” MacArthur wrote to Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, the chief of Pacific naval operations.

MacArthur had already taken Tacloban, but his men faced months of fighting north to Manila. As they did so, Parsons sailed with a group of PT boats ordered to root out Japanese coastal units on Leyte. As he lay in his bunk below deck one night, a Japanese shell destroyed a gun and killed a sailor a few feet above Parsons’ head. He wasn’t injured, but he was coming down with malarial fever. After the mission, he was dispatched to a hospital ship; doctors ordered him to get treatment and rest in the United States. He received both at a Navy hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, close to where his family was living. “We got to see quite a bit of him,” said Peter Parsons, who was then 8 years old. “He played catch with me, bought me a baseball glove and took me to a boxing match.”

But he wasn’t finished with the war. Once he was deemed well, Parsons returned to the Philippines, in January 1945, to coordinate guerrilla units as they fought the Japanese throughout Luzon Island. As MacArthur’s troops converged on Manila in early February, the Japanese made a fierce, final stand to hold the capital, and they kept it up for a solid month.

The death toll from the Battle of Manila was horrific: more than 100,000 Filipinos, the majority of them civilians; most of the 16,000 Japanese military holdouts; and about 1,000 American soldiers. Historians have compared the destruction of Manila to the devastation of Warsaw or the firebombing of Dresden.

Parsons ventured into the city soon after MacArthur finally dislodged the Japanese, on March 4. “Manila is finished, completely demolished,” he wrote in a letter to Travis Ingham. But he had one last mission: finding his mother-in-law.

Her son Tom Jurika had received word that the Japanese might have taken her to Baguio, in northern Luzon, but Parsons had reason to fear the worst. When he had gone in search of a good friend in Manila, Carlos Perez Rubio, he found a gruesome scene: “twenty-two bodies—the entire family including women and children...liquidated in a most brutal fashion. Bayonets mostly.”

More news of his mother-in-law came weeks later from Army investigators. In 1944, a double agent working for the Japanese had turned her in, identifying her as a friend of the resistance. The Kempeitai had rounded her up with Senator Ozámiz and 17 others—“all personal friends of mine, same people who had had cocktail parties with me in my house,” he recalled. They were killed about the same time Parsons was organizing the guerrillas for the invasion at Leyte. Before she was tossed into a mass grave with the others, Blanche Jurika had been tortured and beheaded. “If she could have just lasted another three months,” her son-in-law recalled, “she’d have been all right.”

**********

After Japan surrendered aboard the USS Missouri, on September 2, Parsons began rebuilding his prewar life. “It took my dad about ten seconds or fewer to get back into business,” Peter Parsons told me. “Before the war was actually over he was operating Luzon Stevedoring again, buying out shares of widows and former partners.” He retired from the Navy and returned to the polo field. And despite his anger at the atrocities he’d witnessed, he resumed business with contacts in Tokyo.

Though his exploits were certainly colorful, I came to see why Parsons didn’t believe he was a “colorful character.” His great strength was his capacity to hold to a set of basic principles. In peacetime, that meant supporting his family and finding community among the people of his adopted country. In wartime, facing an existential threat, going to battle, all-out, was the obvious choice. Afterward, his prewar principles held. More than 70 years later, Peter Parsons could summon up a clear image of his father, smiling and waving onshore when a ship brought the family back to Manila. “There he was, waiting for us, like nothing had happened. He never changed, not the war, not the fighting, it did not change him at all.”

Manuel Roxas, the captive general Parsons had contacted on his first spy mission, became the first president of the independent Republic of the Philippines, in 1946. After a Japanese military prisoner identified where Blanche Jurika and the others had been buried, Roxas honored them with a gravestone at the burial site. “We keep it in good shape and put a little fence around it,” Chick Parsons recalled. “It’s quite a little monument, and we’re proud of it.”

For his wartime service he received many honors, including the Distinguished Service Cross, two Navy Crosses, the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart from the United States. Panama gave him the Order of Vasco Núñez. The Philippines awarded him not only its Medal for Valor, but also citizenship, which he was proud to have.

He met Tyrone Power after the actor played a character named Chuck Palmer in a fictional 1950 film, American Guerrilla in the Philippines, but he avoided celebrity. “I don’t think that I’m an important person,” he recalled 36 years after the war. “I don’t think I’ve done anything unusual. I think I’ve been lucky.”

Chick Parsons died in Manila on the afternoon of May 12, 1988, during his siesta. He was 88. His sons—Peter, Michael, Patrick and Joe—gathered for a funeral service there, and they laid him to rest in a grave next to Katsy, who had died eight years before. “He was hardly ever sick in his whole life,” Peter Parsons said. “When he died he was asleep. He coughed or sneezed, and that was it. We called him ‘Iron Man.’”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.