The Women Who Waged War Against Sex Trafficking in San Francisco

“The White Devil’s Daughters” examines the enslavement of Chinese women in the late-19th century and how it was defeated

:focal(2521x614:2522x615)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/d2/11d278ed-ee55-438d-a484-f65aee07c2b3/tien_fuh_wu_standing_in_the_back_on_the_left_and_donaldina_cameron_seated_center_with_a_group_of_women_who_may_have_been_mission_home_staffers___courtesy_of_louis_b_stellman_california_state_library.jpg)

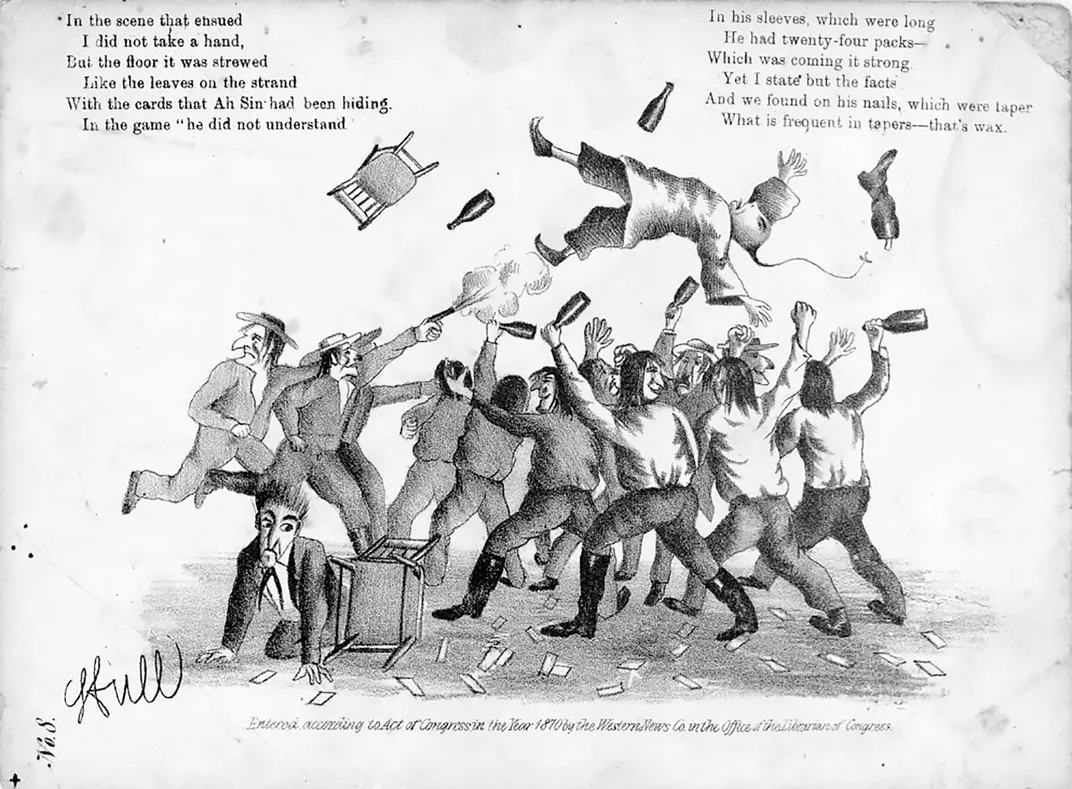

In the 1870s, San Francisco, and the American West generally, was a hotbed of anti-Chinese sentiment. Spurred by racism, exacerbated by the economic uncertainty of an ongoing recession, the xenophobia manifested itself in discriminatory legislation and violent physical intimidation against Chinese men and women. Anti-miscegenation laws and restrictive policies that prohibited Chinese women from immigrating to the U.S. created a market for human trafficking, which corrupt officials overlooked.

“In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, many women in Chinatown ended up working as prostitutes, some because they were tricked or sold outright by their families,” writes journalist Julia Flynn Siler in her new book, The White Devil’s Daughters. “They were forbidden to come and go as they pleased, and if they refused the wishes of their owners, they faced brutal punishments, even death.”

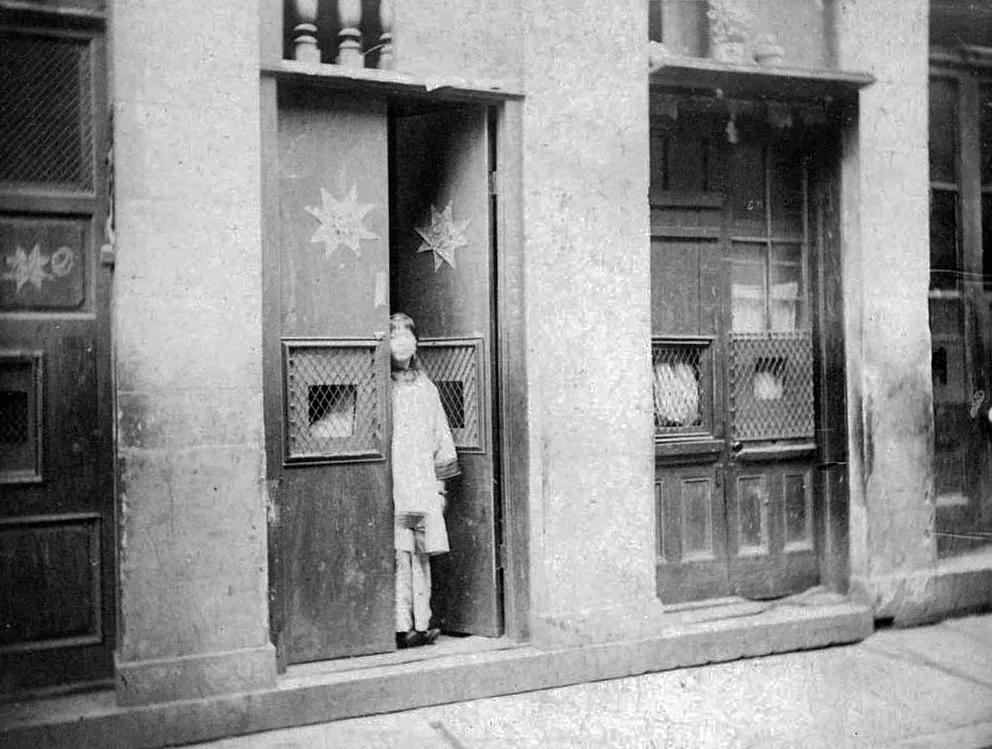

Motivated by their Christian faith, a group of white women set out to offer the immigrant women a path out of slavery and sex trafficking and, ideally, into what they viewed as good Christian marriages. In 1874, they founded the Occidental Board Presbyterian Mission House and, for the next six decades, more than 2,000 women passed through the doors of the brick building at 920 Sacramento Street, San Francisco. Among them were Bessie Jeong, who became the first Chinese woman to graduate from Stanford University, Tye Leung Schulze, one of the first Chinese-American women to vote in the U.S. and who worked as a translator at Angel Island immigration station, and Yamada Waka, who returned to her home country of Japan to become a leading feminist there.

The White Devil's Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco's Chinatown

A revelatory history of the trafficking of young Asian girls that flourished in San Francisco during the first hundred years of Chinese immigration (1848-1943) and an in-depth look at the "safe house" that became a refuge for those seeking their freedom

Smithsonian spoke with Flynn Siler about the Mission House’s history, this early anti-trafficking effort and why this story is still relevant today.

Slavery was technically outlawed in the United States with the passage of the 13th Amendment, but another type of slavery exploded in California in the years following. What was this “other slavery,” and why was it allowed to continue?

It was what we now describe as the trafficking of women from China to the west coast. Those women were literally sold at auction in the 1860s and the 1870s on the wharf of San Francisco. Later on, those sales started to go underground, but the trafficking of women for sex slavery, for forced prostitution, continued into the early 20th century. It continues today, but not in the way you would see hundreds of women coming off ships and being sold.

What role did the U.S.’s immigration policies play in this new slavery? Was San Francisco's government or the police force doing anything to curb the trafficking?

The immigration policies played a very dramatic role and led to the very striking imbalance in genders. The Page Act, which barred most Chinese and Asian women from entering the United States, was an effort to try to stop so-called prostitutes from entering the country. In the 1870s there were 10 Chinese men for every one Chinese woman [living in San Francisco]. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act [banned all labor immigrants from China and] only allowed a certain class of Chinese person, including merchants and students, to come into the United States.

This immigration policy backfired in that [the immigration of] Chinese women was restricted, but there was a huge demand for Chinese women from men who were very far away from their families. So criminal elements seized on this opportunity and recognized that it could become very lucrative to bring women into the country for sex.

Enormous corruption amongst the police force and city government through the latter half of the 19th century actively helped the trafficking and the traffickers used it to their advantage.

What was the Occidental Mission House? What motivated the women who founded the home?

This story begins with a visiting missionary from China and was describing the condition of Chinese girls and women there. A group, mostly of missionaries’ wives, got together and they decided they wanted to try to do something. They soon realized that instead of looking to try to help girls and women in China, they should look closer to home in that the girls and women that were literally on their doorsteps were suffering very greatly and that it was an incredible opportunity to try to reach out to them.

They decided to exercise power in a way that was open to them, which was to found a home, a charitable enterprise. The purpose was to provide refuge to girls and women who had been trafficked into sex slavery or prostitution. It was also, of course, to try to share their Christian faith with them.

What started as a trickle in women taking up the missionaries on their offer, grew exponentially. By the 1880s, the home was filled with 40, 50, 60 girls and women living there at any one time. Often, some would stay for a day or two, some would stay for a few months, some would stay for years and go to work in the home themselves.

Your book primarily focuses on Donaldina Cameron, the superintendent of the home. Even the book’s title comes from the racial epithet the Chinese traffickers used for her. What challenges did she face?

Over the course of the decades that she ran the home, Cameron encountered a lot of resistance, both from white policeman and white city officials as well as the criminal Tong [Chinese secret society] members who were involved in the trafficking of women from China to San Francisco.

How did the young immigrant women and girls come to the mission?

Some of the women heard about the home, ironically, from their traffickers who spread rumors about it. The traffickers would say, “Don't go to the White Devil's house at 920 Sacramento Street, because the food is poisoned,” or “She eats babies.”

In other cases, people who were trying to help them within the Chinese community would say, “Look, there is a place for you to go if you want to try to leave your situation.” The first example in the book is an example of a young woman who seized an opportunity when she was briefly left alone while having her hair done, to run the five blocks from the beauty shop on Jackson Street in San Francisco's Chinatown, to the mission home.

In other instances, the missionary workers, usually someone like Cameron plus a Chinese worker at the home, would raid a brothel, or would hear that a girl was in distress. Often accompanied by a policeman or some other authority figure, they would find a way in and find a girl who was in distress. That's what she would call “rescue work.”

Once the women and girls entered the home, what did their lives look like?

Their lives were very regulated. There was a set breakfast time, there were prayers. All the girls were required to do chores around the house, to sweep up, to cook. In the later years classes taught them how to sew. There were English classes, there were Chinese classes. There was an opportunity for some sort of an education, and that was a very striking thing because Chinese girls in San Francisco were not often formally educated.

They would go church at least once a week. Sometimes in the summer they might take a venture out into what they would call “the country,” to pick fruit. The mission home was always run on a shoestring, and so the girls were put to work to try to help support the house and support themselves as well.

Did any of the residents resist the religion? How was that responded to?

My impression, having read everything I could find in terms of Dolly's official writings to her Board, church records, as well as her private writings in her diaries, was that she was a very pragmatic woman. She was very motivated by her own faith, but I did not get the sense that she ever was angry or disappointed if other people did not share or find her faith.

The mission home did report the number of baptisms, for example, but often it was three baptisms in a year and they would have more than 100 women pass through the home. As time went on, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s from there, it really was evolving towards more of a social services home. I just think they were very clear that not all of the girls who went passing through there would share their faith.

Marriage was seen as the ultimate goal at the Mission House. What were those partnerships like?

The mission home became a de facto marriage bureau. The gender imbalance not only in the West, but across the country, amongst Chinese men was still in place. [For] Chinese men who wanted to marry in the United States, it wasn’t that easy to find a Chinese woman. So word got out that there were Chinese women in the mission home. It was very much part of the late Victorian ethos amongst the mission home workers that their goal was to create a family, and ideally a good, Christian family.

They would set criteria for men who came asking for the hands of some of the women who lived at the home. I mean they were hoping that they, too, were Christians, and that they had stable jobs, and that their requests were not just a ruse to get these women back into a forced prostitution.

Some academics have written about the ethnocentrism and racism that shaped the home’s founding and the goals. Is it fair to see these religious women as part of the “White Savior Complex”?

I think it’s a fascinating discussion, and I tried to address that question by focusing on the Chinese and other Asian women who worked at the home, and the stories of the women who came through the home. This book is not a book primarily about the white superintendents of the home—it is primarily about the women who found their freedom at the home.

I feel like I’ve gotten to know Dolly Cameron pretty well, spending the last six years thinking about her and researching her. I don’t think personally that she had a White Savior Complex, but I do agree with those critics who make the good point that the racist language that she and other white missionary workers used in describing the girls and women who came to the home is something that is jarring and wrong to our ears today.

Who are some of the women who “found their freedom” at the home? Which ones really stuck with you?

The book begins and ends with one of the most famous crime cases of the 1930s on the West Coast. It was given the name by newspaper men of the “broken blossoms” case. A group of trafficked women found the courage, with the help of the mission home workers, to testify against their traffickers.

Those stories are astonishing, and as a historian I was very lucky to have just a wealth of material to try to document their journey. The woman that I begin the book with [Jeung Gwai Ying]—she was with child and she had her child during the period that she was in this legal battle. I so admired the sheer courage it took to do something like that, to testify against people who were a lot more powerful than she was.

The other one that is just so searing to me was a case of Yamada Waka, an extraordinary Japanese woman who came to the home right at the turn of the 20th century. She had been trafficked and forced into prostitution in Seattle. She made her way down to San Francisco, escaping that situation with the help of a Japanese journalist. When she got to San Francisco, almost unbelievably the journalist tried to force her back into prostitution. She fled to the mission home.

The most notable stories are ones where the women chose to go to the home and to use it as a launching pad for their own freedom. [Waka] is so memorable because she was self-educated. She found her education at the mission home. She probably was not literate before she got there. She was apparently an absolutely brilliant woman.

She found her husband through classes at the mission home. Then he and she returned to Japan and she became a very, very well-known feminist writer in Japan. Not only that, but she opened up a home of her own in Japan modeled on the one in the mission home to try to help other women.

Her story is very much one of agency, of education and of empowerment. Her description of her experience of being forced into prostitution was absolutely searing.

Tien Fuh Wu was one of the women who stayed at the home and assisted Dolly in her mission. Can you describe their partnership?

She was very much, I would argue, an equal partner to Dolly. In some ways, my book can be seen as a story of an extraordinary friendship between two women who were so different from each other and came from such different places. Tien Wu had been sold by her father in China to pay his gambling debts, and she was sent to San Francisco to work as a mui tsai, a child servant.

One pattern of that type of servitude was that once those girls came of age, they would sometimes end up as prostitutes. Tien Wu found herself working in a brothel in San Francisco's Chinatown, and then was sold from there to two women. They badly mistreated her and burned her. A neighbor, somebody in Chinatown, sent a note to the mission home alerting them of the condition of this poor girl, so a rescue was staged by the missionary workers to get her.

She was brought to the mission home. We don’t know of her exact age at that point, but she took classes, settled in and played with the other girls.

At first, she didn't like Dolly at all and resented Dolly as a newcomer, because Tien had arrived 15 months before Dolly started as a sewing teacher in the 1890s. Tien was an intelligent young woman who had the benefit of a sponsor who paid for her education, so she went back east for school and then made the choice to come back to the mission home in San Francisco and work as Dolly's aide.

One of the most touching parts of their story is the fact that they spent their whole lives together—neither married, neither had children. I went into Los Angeles to visit the grave site where they’re both buried. It's a story of radical empathy, of a friendship between two vastly different people coming together for the same aim: to help other women.

What relevance does this story have today?

I would say that this is an early #MeToo story. This is a story of women standing up for other women. This is a feminist story. This is a story of an early effort to fight human trafficking, to fight modern slavery.

This incredibly small group of [the founding] women who had virtually no power in their lives. They couldn't vote. Their husbands and fathers didn’t really want them out in the public sphere. That wasn’t acceptable to middle-class white women at that time. This is one way that they could exercise power, to set up a home.

It was an act of radical empathy, to care about a group of people who were widely scorned in the West. At the same time they opened the home, there was widespread violence towards the Chinese immigrants. This small group of women said, “No, we’re going to offer a safe place. We’re going to offer a sanctuary.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.