Women On the Frontlines of WWI Came to Operate Telephones

The “Hello Girls” risked their lives to run military communications—and were denied recognition when they returned home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/61/5761bee3-f6de-4c81-b741-bf8546880a79/trio-at-switchboard.jpg)

Several weeks before President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, the United States became the world’s first modern nation to enlist women in its armed forces. It was a measure of how desperate the country was for soldiers and personnel to assist with operations stateside, and American women seized the opportunity to prove their patriotism.

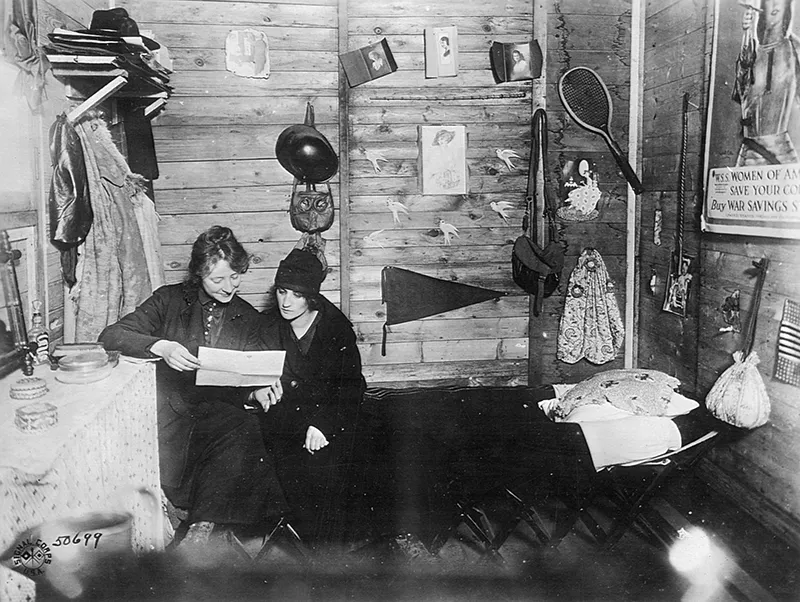

Initially, they worked as clerks and journalists. But by late 1917, General John Pershing declared he needed women on the frontlines for an even more crucial role: to operate the switchboards that linked up telephones across the front. The women would work for the Signal Corps, and came to be known as the “Hello Girls.”

These intrepid women are the subject of Elizabeth Cobbs’ new book, The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers. “Telephones were the only military technology in which the United States enjoyed clear superiority,” Cobbs writes, and women were by far the best operators. At the start of the 20th century, 80 percent of all telephone operators were women, and they could generally connect five calls in the time it took a man to do one.

When the United States declared war, the Signal Corps had only 11 officers and 10 men in its Washington office, and an additional 1,570 enlisted men around the country. The Army needed more operators, bilingual ones especially, and it needed them quickly. Fortunately, women were quick to respond. In the first week of December 1918, before the War Department even had the chance to print out applications, they received 7,600 letters from women enquiring about the first 100 positions in the Signal Corps. Eventually 223 American women were sent across the ocean to work at Army switchboards across Europe.

To learn more about these women and the role of telephones in the war, Smithsonian.com talked to Cobbs about her research.

What brought you to this subject?

I was searching for a topic for a new book a couple years go, thinking about [the WWI] centennial, and we probably didn’t need another thing about Woodrow Wilson, though someone will write it. In the context of all that, I can’t remember how I tripped across these women, but it struck me there was an important story here. [Women in the military] is one of those problems that seems very new, and yet it’s something women were experiencing 100 years ago.

How did you find information about the women featured in your book?

There wasn’t much. When I talk with some people they say, ‘How can you write this story? These are obscure people.’ I was aware that Mark Hough, a young man in his 20s in the 1970s, became a champion for the women. I went to the Seattle Bar Association, contacted them, asked can you get me in touch with him? They had an old email, tried a few times and didn’t hear back, and after a couple months I heard back. He said, ‘Oh yeah, this is me. I’ve been in Bosnia and Iraq for eight years, and I have three boxes of materials from the Hello Girls. I worked with them for several years to get [them recognized by Congress].’

He had a box that was memorabilia the women shared with him. They didn’t want to see it lost forever. One of the first things he showed me was a charm-bracelet-size pair of binoculars. He said, ‘Take a peek, you can see in them.’ I put this penny-sized pair of binoculars on, and I took a peek. I see a glimmer and I think it’s his shelves, the room. But then I’m looking through them and on the other side are these perfectly crisp pictures of naked women! French pornography of the 1910s, it was very tasteful. These were the things the women brought back from WWI, which also gives you a peek into their own mindset, their sense of humor, their willingness to laugh at their circumstances and themselves.

What role did the telephone play in getting women to the front?

The way this worked in WWI was the telephone was the key instrument in the war. Telegraphs operated on Morse code and it was a slower process. As a general, you couldn’t talk to somebody directly. The radios were similar. To get a radio field unit required three mules to carry it. The other problem with radios was that there wasn’t any measure for disguising the transmission so they weren’t secure forms yet. The signal could be plucked out of the air and you could trace where it came from. Telephones were secure and immediate; they were the primary way men communicated. In WWI, telephones then were called candlestick phones. You lifted up the speaker tube and you would tell them who you wanted to talk to, and then every call had to be connected manually.

Women were really the best doing this job. General Pershing insisted when he got over, they needed bilingual women [to operate the switch boards]. The way telephones worked with long distance was an operator talked to another operator, who talked to another, and the call was relayed across the multiple lines. The U.S. ultimately ran an entirely new telephone system all throughout France that would allow operators to talk with English-speaking operators. But when they first got there they were interacting with French lines and French women. These were generals and operators who had to communicate across lines with their counterpart in other cultures. An American officer might not speak French, and a French officer might not speak English, so the women also acted as simultaneous translation. They were not only constantly fielding simultaneous calls, they were translating, too. It was this extremely high-paced operation that involved a variety of tasks. They were sweeping the boards, translating, even doing things like giving the time. Artillery kept calling them and saying, can I have the time operator? The women were really critical.

And the women who were working for the Signal Corps, a number at the end of their shifts would go to the evacuation hospitals, they’d talk to the men and keep up their spirits. One night Bertha Hunt [a member of the Signal Corps] was on the lines and wrote about just talking to men on the front lines. They would call just to hear a woman’s voice.

Was sexism a major issue the women had to deal with on the front?

I think sexism falls away fastest under fire because people realize they just have to rely on each other. Yes, the women encountered sexism, and there were some men who were grumpy, who said, ‘What are you doing here?’ But as soon as the women started to perform, they found the men were very grateful and very willing to let them do their job, because their job was so critical. It created this enormous camaraderie and mutual respect.

At the same time as women were going to war, the suffrage movement was coming to a head in the U.S. How did these two things go together?

Worldwide, the war was the thing that enabled women in multiple countries to get the vote. In the U.S., they’d been fighting for 60 years and it went nowhere. Curiously, it’s women elsewhere who get the vote first—20 other countries, even though the demand was first made in the U.S.

The women’s suffrage movement brings the topic to fruition, but it’s women’s wartime service that converts people. For Wilson, it’s also the knowledge that the U.S. is way behind the implementation of liberal democracy. Women’s suffrage becomes intertwined in his foreign policy. How can we claim to be the leaders of the free world when we’re not doing what everybody else is doing? Are we going to be last to learn this lesson?

If you’re a full citizen, you defend the republic. One of the longtime arguments [against suffrage] had been women don’t have to pay the consequences. The vote should be given to people who are willing to give their lives if necessary. With the war, the women could say, ‘How can you deny us the vote if we’re willing to lay down our lives?’

You follow the journeys of several women in the book. Are there any that you felt an especially close connection to?

My two heroines are Grace Banker and Merle Egan. You identify with them all, but with Grace, I love the fact that here’s this 25-year-old woman who one day, doesn’t know if she’ll even be inducted and five days later is told she’s going to head this unit—the first women’s unit in America to serve in this particular capacity, the first official group of women’s soldiers. Everybody all over the U.S. was talking about them doing this unusual thing, and she writes in her diary, ‘I suddenly realize this duty settling on my shoulders.’ I found her desire to rise to the occasion very moving.

She was also a naughty girl, because you’re not supposed to keep a diary—it’s against the rules. I said to myself, I wonder why she would do this? I wonder if maybe she liked history? So I went to Barnard and said, ‘Can you tell me what Grace Banker’s major was?’ They said she was a double major, history and French. She had an eye to history, and I love that about her. Grace is just this firecracker. At one point, she’s talking in her diary about this person who came in who’s such a bore, and she went out the back window.

With Merle Egan, I found it so poignant that throughout the decades, this lonely fight [for recognition], she keeps it up. For her the meaning of old age wasn’t to slow down, but to hurry up. Her files and her letters and her campaign intensified when she was in her 80s. She knew she didn’t have much time left. By this time the second wave of feminism had come up. She hops on the second wave, and it’s really a story also about men and women working together. Mark Hough and General Pershing were men who saw that women were people too and wanted to recognize women’s service and give women the opportunity to serve and fully live out the meaning of citizenship.

Merle’s story is really interesting. She comes back to the U.S. after being the switchboard operator at the Versailles peace conference, and she’s denied any recognition of her service. What was that like for them?

At 91, Merle got her victory medal and said, ‘I deserve this as much for fighting the U.S. Army for 60 years as for heading up the switchboard for the Versailles conference.’ The women were not given discharges at the same time because somebody had to stay behind and run communications. Men who went home for the armistice were followed six months or even a year later by the women, because they weren’t discharged until the army was done with them. They got home and—here’s the totally bizarre thing that tells you the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing in government—the Navy and Marines formally inducted 11,000 women to serve in roles at home, clerks, telephone operators and journalists. But the Army took in a much smaller group of people, only 300 women altogether, and they hated the idea of inducting anybody.

The women found, if they were in the Army, despite everything they understood, when they got home the Army said you weren’t in the Army. You never took an oath. And there were multiple oaths in the files for them. One of them, their leader Grace Banker, won the Distinguished Service Medal awarded by Pershing, which was the top medal for officer at that time. Despite all that, they were told, ‘You weren’t actually in the Army.’ And of course it was heartbreaking for these women. A majority did what soldiers do, they buttoned it up and moved on with their lives, but a group said this isn’t right. Especially Merle Egan. There were women who died, two who lost their lives in influenza, and several were disabled. One woman’s arm was permanently disabled because somebody had treated it improperly and she ended up with permanent nerve damage. Another had tuberculosis. The Army, unlike the Marines and Navy, which provided medical benefits, said, that’s not our problem.

We’re still having these arguments today, about women’s role in combat. Do you think things have improved since WWI?

I think there has been a lot of change and there remains a lot of resistance. The WWI women got on the same piece of legislation as the WWII women in the Army, who were also denied full status as military personnel. One of their jobs was to tow targets for other soldiers to shoot at. Women in that group [the Women Airforce Service Pilots] were being denied burial rights at Arlington [until 2016] because they weren’t real soldiers. Despite the legislation headed by Barry Goldwater that overturned the original ruling, the Army was coming back again and saying, we don’t have to obey that.

Remembering and forgetting that women are real people, full citizens, is something that it seems we encounter in every generation. People have to be reminded, the fight has to be taken up again, but at a different point. There has been real progress, but you can’t take it for granted.

Editor's Note, April 5, 2017: The article previously misstated that General John Pershing needed women on the frontlines at the end of 1918.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)