These Women Reporters Went Undercover to Get the Most Important Scoops of Their Day

Writing under pseudonyms, the so-called girl stunt reporters of the late 19th century played a major role in exposing the nation’s ills

:focal(556x66:557x67)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/21/d121d07e-47db-4b2f-8f63-fe1e046decd1/nov2016_c03_girlstuntreporters-wr-v2.jpg)

One November day in 1888, a slight, dark-haired young woman ducked out of the crowd on a street in downtown Chicago and took an elevator up to see a doctor. She’d been uneasy all morning, an unpleasant task ahead. Lines from Thomas Hood’s poem about suicide ran through her mind: “One more unfortunate, / weary of breath / Vastly importunate, / Gone to her death.”

But Dr. C.C.P. Silva had a good reputation to go with his black goatee and slight paunch. Frequently featured in the Chicago Tribune, he was the surgeon for the city police department and on the faculty of a medical school. In Silva’s office, accompanied by a man claiming to be her brother, she told the doctor she was in trouble. Could he help?

What she wanted was dangerous, Silva answered—the risk of inflammation or complications—and added, “It must also be perfectly secret. To let a single breath of it out would be damaging to you, damaging to the man, and to me.”

Then he told the man to find a place for her to stay and agreed to perform the operation for $75. The young woman must have assured him she could keep a secret.

She would keep his, for a few weeks. She has kept hers for more than a hundred years.

The young woman was one of the nation’s so-called girl stunt reporters, female newspaper writers in the 1880s and ’90s who went undercover and into danger to reveal institutional urban ills: stifling factories, child labor, unscrupulous doctors, all kinds of scams and cheats. In first-person stories that stretched over weeks, like serialized novels, the heroines offered a vision of womanhood that hadn’t appeared in newspapers before—brave and charming, fiercely independent, professional and ambitious, yet unabashedly female.

It was the heyday of the 19th-century daily newspaper. As new technology made printing cheaper, publishers cut newspaper prices to attract residents of the burgeoning cities—recent immigrants, factory workers. This huge potential audience gave rise to a rough competition waged with weapons of scandal and innovation.

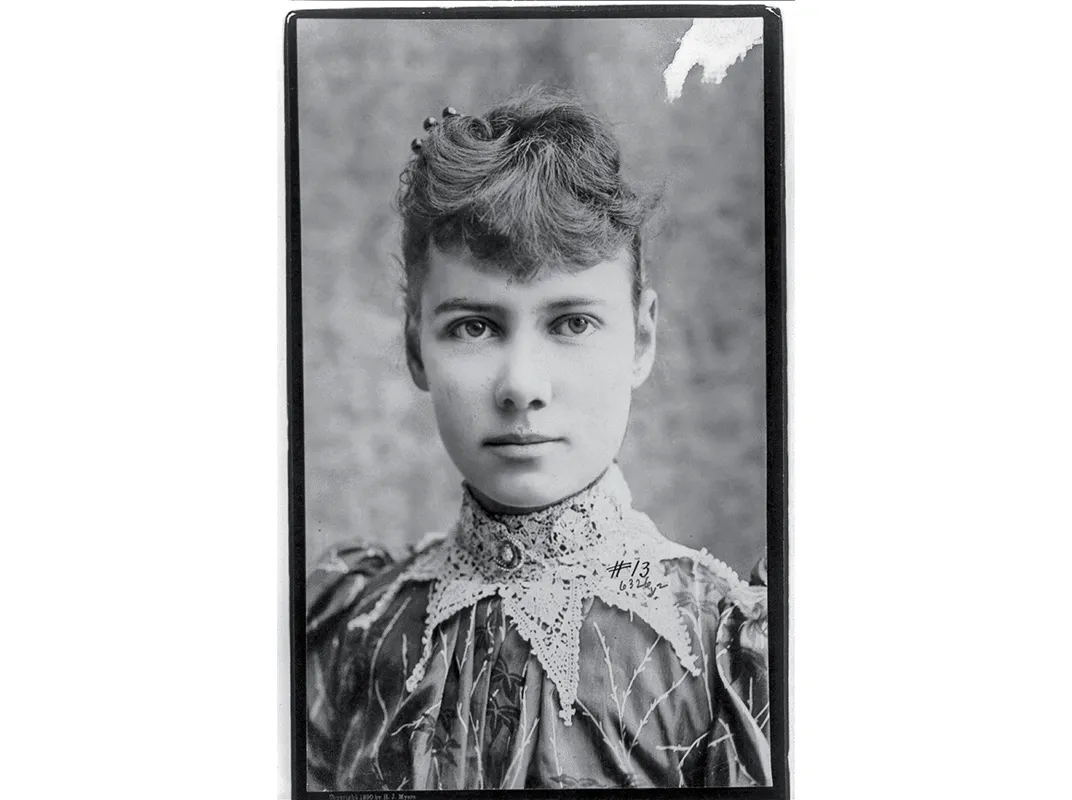

After Nellie Bly, whose 1887 series “Ten Days in a Mad House” had been a windfall for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, everyone wanted a girl stunt reporter. In little more than two years after Bly got herself committed to New York City’s notorious Blackwell’s Island insane asylum, Annie Laurie fainted in a San Francisco street to report for the Examiner on her ill treatment at a public hospital. For the St. Paul Daily Globe, Eva Gay slipped into an industrial laundry to interview women sickened by the damp. Nora Marks reported for the Chicago Tribune on boys as young as 10 being held for trial at the Cook County Jail, some for more than a month.

Their reporting had real-world consequences, increasing funding to treat the mentally ill and inspiring labor organizations that pushed for protective laws. And they were so popular that, while in 1880 it was practically impossible for a female reporter to get off the ladies’ page, by 1900 more articles had women’s bylines than men’s.

The names in the bylines, however, were often fake. Stunt reporters relied on pseudonyms, which offered protection as they waded deep into unladylike territory to poke sticks at powerful men. Annie Laurie was really Winifred Sweet; Gay was Eva Valesh; Marks was Eleanor Stackhouse. Even Nellie Bly was a false name, for Elizabeth Cochrane. “Many of the brightest women frequently disguise their identity, not under one nom de plume, but under half a dozen,” wrote a male editor for the trade publication The Journalist in 1889. “This renders anything like a solid reputation almost impossible.”

Compared with muckrakers who came after—Jacob Riis and his gritty photographs in the book How the Other Half Lives; Ida Tarbell and her reporting on rot at the heart of the Standard Oil Company in 1902; Upton Sinclair and The Jungle, his novel about meatpacking plants—the stunt reporters are little known, little respected. Some never emerged from under cover.

One of these was the woman who wrote the Chicago Times’ abortion exposé in 1888, under the byline “Girl Reporter.” Her personal story, shards of which can be pieced together from newspaper clippings, legal records and musty professional directories, offers perhaps the starkest example of these journalists’ assertion of a female identity—and its erasure over time.

In Illinois, an 1867 statute made it illegal for a doctor to provide an abortion, under the penalty of two to ten years in jail. An exception was made for bona fide medical or surgical purposes. By her count, the Girl Reporter visited more than 200 doctors over three weeks, pleading, crying, taking notes. A medical journal referred to her, sneeringly, as the “weeping beauty.” She documented fees ranging from $40 to $250 (about $1,000 to $6,000 in today’s currency). Among those who agreed to perform an abortion or refer her to someone who would was Dr. J.H. Etheridge, president of the Chicago Medical Society. Her series is the earliest known in-depth study of illegal abortion, according to Leslie Reagan, a historian who has written extensively on women’s health and the law.

Deciphering history, particularly the private lives of women, can be like peering through warped and clouded glass. The Girl Reporter flung the window open. In scene after scene, people have the kinds of conversations that never make it into textbooks. And while the stated purpose of the exposé was “the correction of an awful evil,” it showed the complexity and nuance of the forbidden practice.

“It’s an extremely rare source,” Reagan told me when I called to ask if she had any idea who the reporter might have been. (She didn’t.) “It’s just kind of this amazing thing. I never found anything like it anywhere else.”

**********

The Chicago Times was an unlikely candidate for journalistic excellence. Anti-Lincoln and pro-slavery during the Civil War, it was infamous for spewing inflammatory rhetoric and unearthing things best left buried. A former reporter summed up its early years this way: “Scandals in private life, revolting details from the evidence taken in police court trials, imaginary liaisons of a filthy character, reeked, seethed like a hell’s broth in the Times’ cauldrons and made a stench in the nostrils of decent people.”

But when a new publisher, James J. West, took over at the end of 1887, he determined that it would soon be “one of the ablest and handsomest journals in the world” and cast about for ways to make that happen: new type, fiction by the British adventure writer H. Rider Haggard, a Times-sponsored plan to find bison in Texas, domesticate them and save them from extinction. A writer would file exclusive reports by carrier pigeon.

Nothing worked, though, until a schoolteacher-turned-reporter named Helen Cusack donned a shabby frock and brown veil and went looking for a job in the rainy July of 1888. In factories and sweat shops, she stitched coats and shoe linings, interviewed her fellow workers in hot, unventilated spaces and did the math. At the Excelsior Underwear Company, she was handed a stack of shirts to sew—80 cents a dozen—and then was charged 50 cents to rent the sewing machine and 35 cents for thread. Nearby, another woman was being yelled at for leaving oil stains on chemises. She’d have to pay to launder them. “But worse than broken shoes, ragged clothes, filthy closets, poor light, high temperature, and vitiated atmosphere was the cruel treatment by the people in authority,” she wrote under the byline Nell Nelson. Her series, “City Slave Girls,” ran for weeks.

Circulation surged, and West doubled down on stunt reporting. He approached Charles Chapin, his city editor, and revealed his newest brainstorm. Horrified, calling it the “yellowest” idea he’d ever heard in a newspaper office, Chapin refused to have anything to do with it.

He thought West had forgotten about it, even when the publisher requested a “bright man and a woman reporter” for a special assignment. But in early December, Chapin recalled, he went into the composing room and saw the headline: “Chicago Abortioners.” He quit before the paper hit the streets. (That exact wording doesn’t appear in the series, but Chapin’s memory might have faded: He wrote his account 32 years later, in Sing Sing, where he was serving time for killing his wife.)

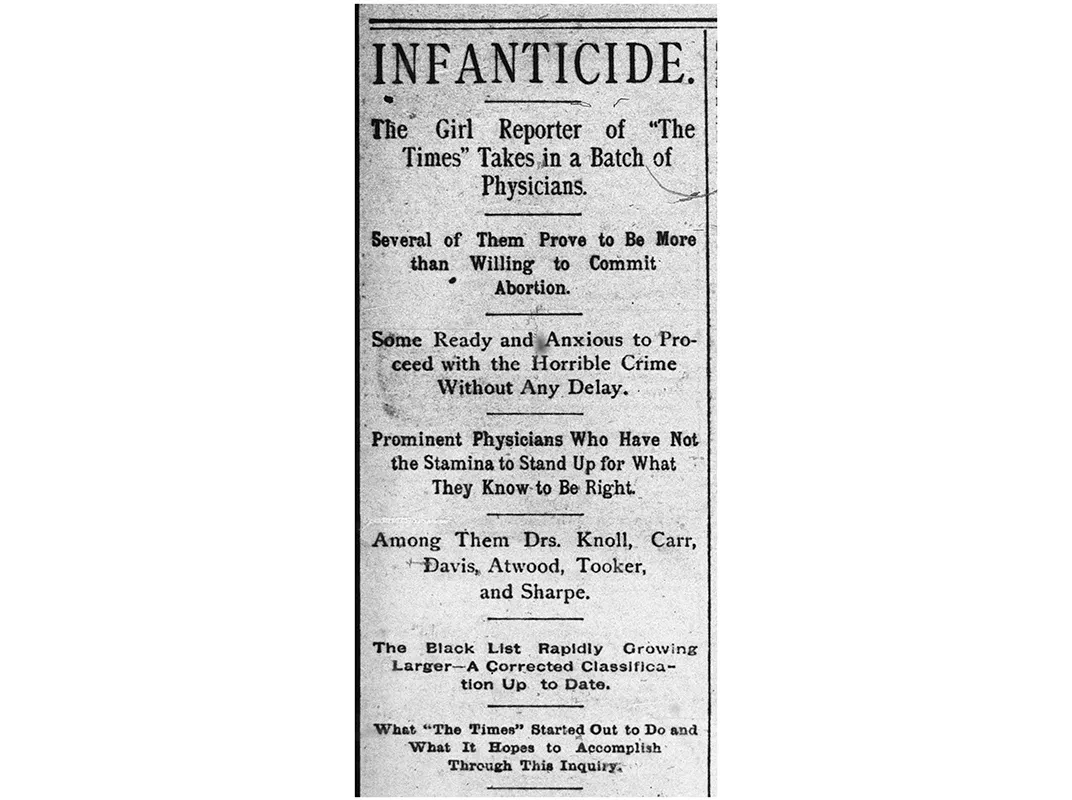

In the initial articles, under the all-caps headline “INFANTICIDE,” a male reporter asked cabmen where he could find relief for a relative who had been “led into error.” He met German and Scandinavian midwives in the poorer section of the city and made his case. Some proposed medicines and places for her to stay during recovery. Others said they could help with adoption. But most demanded to see the young woman in question.

Enter the Girl Reporter.

She and her male colleague refined their story over the next few days, switching from midwives to prominent doctors, claiming she was six weeks pregnant rather than two or three months, stressing that money was no object.

The Girl Reporter spent long days going from office to office. She visited Dr. Sarah Hackett Stevenson, who treated her kindly but advised her to have the child and get married, even if it would be “but a step toward divorce.” She interrupted Dr. John Chaffee at his lunch, and he urged her to have the operation right away, telling her, “Thousands are doing it all the time. The only thing to do when one gets into trouble is to get out again.” (A few days later, Chaffee was arrested for giving a woman an abortion that killed her.) Dr. Edwin Hale, a controversial figure since publishing his pamphlet “On the Homeopathic Treatment of Abortion,” gave the reporter a bottle of big, black (and harmless, the doctor assured her) pills to take before admitting herself to the hospital. That way, when he was called to her bedside, and performed the operation surreptitiously, they could blame the medication for causing the abortion.

Beyond the value of the Girl Reporter’s research was her voice. She’s determined: “I felt that there was some big ruffians to be brought down yet, and I was anxious to have a composed mind and a strong heart.” She’s weary: “Tonight as I write this I am sick of the whole business. I did not suppose there was so much rascality among the ‘reputable’ people.” Her prose teemed with self-conscious literary flourishes—puns and alliteration, references to Shakespeare and the Aeneid. This, alternating with casual exclamations, like “ugh” and “really swell,” the gushing enthusiasm for favorite novels and her Sunday-school moralizing, all seem like the first attempts of a big reader and beginning writer. There’s the sense of a real person trying to figure things out.

Righteous anger filled her at first, at the doctors and the women who sought them out, but then something shifted.

“I found that I was beginning to be somewhat of an adept at deceit and this rather startled me,” she wrote. “I began to be suspicious of myself. I have talked so much of my pretended trouble to the doctors that I now and then permitted my thoughts to wander and drift into the channels where it had been wading though the day.” She felt for the woman she feigned to be. Eventually, she cared less about a willingness to commit abortion and more about the failure to sympathize with women in dire straits. When a doctor refused coldly, she imagined saying, “Don’t prate of virtue to me. I am as good as the rest of the world only less lucky.”

In one installment, she mulled over her assignment and the disconcerting feeling that in constantly pretending to be someone else, she was losing her individuality, her sense of self.

“Today I have been wondering whether, if I had to do it over again, I would have taken a position on a newspaper staff,” she wrote. “It used to be the dream of my childhood that I would some day become a writer—a great writer—and astonish the world with my work,” she wrote.

“But did I ever suppose that I would have to commence on a newspaper by filling an assignment like this?

“Well, no.”

As a cub reporter, she was prepared to compete on the same terms as men. But this assignment was entirely different: “A man couldn’t have done it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/12/d8125762-92df-497b-9117-771013ae6443/nov2016_c05_girlstuntreporters.jpg)

**********

The abortion exposé was West’s dream—a sensation. The Times, which eight months before had run ads for an abortifacient marketed as Chichester’s English Pennyroyal Pills, packed its editorial page with demands that the law be enforced, abortion stamped out. The paper proposed remedies. Women needed instruction on the delights of motherhood. Maybe there should be a lying-in hospital. Or doctors should meet stricter certification requirements. Preachers shouldn’t be squeamish about addressing abortion from the pulpit.

Letters to the editor poured in deep into January, bubbling with praise and outrage and frank evaluations of relations between the sexes. A father wrote in to say he had originally shielded his 18-year-old daughter from the articles, but decided he needed to “take the bull by the horns” and let her read them. Another letter, under the title “Bring the Husbands to Book,” raised the issue of rape. Still another, from a female doctor, said patients had asked her for abortions 300 times in her first year of practice. A doctor who didn’t sign his name confessed that the Girl Reporter’s entreaties might have swayed him. He had turned a woman away, only to be called to her family’s house days later, after she had killed herself. “It is our duty to preserve life whenever possible. Did I do it?” he asked.

Though the Times’ editorials railed against the evils of “infanticide,” the paper’s reportage raised more questions than it answered. That 18-year-old whose father reluctantly handed over the front page? Despite the paper’s moralizing, it would be hard for her to avoid the impression that abortion was common, available to anyone who could steel herself to ask for it. She might even meet with kindness and understanding. Readers received an education in techniques, specific medicines to take and at what dosage. As many readers dourly predicted, no one was arrested (though Dr. Silva was fired as police surgeon). They suggested the series could be read as an advertisement for the doctors listed, rather than a public shaming.

The Times capitalized on curiosity about the Girl Reporter. An illustration on the editorial page showed five sketches of thin, dark-haired women with bangs in front and a bun in the back, wearing an apron over a collared shirt. They looked down, or up, with expressions pensive or half-smiling, line-drawn Mona Lisas. Underneath was written: “Guess which one of the above is the ‘girl reporter’?”

I started guessing.

**********

How many female reporters could there have been in Chicago in 1888? Who might have crossed paths with the Chicago Times?

So many, it turns out.

Nell Nelson, hired by the New York World after her success with “City Slave Girls,” had just left town. Elia Peattie, who wrote about ghosts for the Tribune, was headed to Nebraska. Either might have lingered to do one last Chicago piece. Nora Marks had the perfect training as the Tribune’s stunt reporter. Elizabeth Jordan, who would write for the World and become the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, hadn’t yet left Milwaukee, but she was filing reports for Chicago papers.

Highlighting labor conditions and syndicated to rural papers, Nell Nelson’s “City Slave Girls” series delivered a warning to young women who might have been tempted by city lights. (Image Credits: Library of Congress)

Casting a net beyond the bounds of Illinois was even more daunting. Not long after the Girl Reporter finished her series, The Journalist came out with a 20-page issue highlighting women writers, including two pages on African-American reporters, from Mary E. Britton, who edited a column for the Lexington Herald, to Ida B. Wells, who reported on racial inequality for the Evening Star. It offered no clue to the Girl Reporter’s name.

But the popularity of her series offered a path toward her identity: Big sales also meant lawsuits. One Dr. Reynolds sued for libel and $25,000 because his name could be confused with another Dr. Reynolds who was listed under “Physicians Who Recommend Others Who Would Commit Abortion.” Days later, Dr. Walter Knoll sued for $25,000. In January, Dr. Silva sued the Times for $50,000 and the Chicago Mail, also owned by West, for another $50,000.

Surveying the litigation landscape, the Rochelle Herald commented, “That lady reporter of theirs will have a mighty heap of trouble on her hands if she has to attend to all their cases in court as a witness.”

A witness with a name, I realized, one who might have been called to testify.

**********

At the building for the Circuit Court of Cook County, citizens wandered through with kids in tow, looking confused, asking for traffic control or divorce court. But the archive was quiet.

A week before, waiting for the files I requested to come in, I’d searched through online databases of rival papers, which might have been eager to out the Girl Reporter. The Daily Inter Ocean mentioned that Silva didn’t sue just the paper and West, like everyone else; he also sued two men and a woman: “Florence Noble, alias Margaret Noble.” A small-town paper also wrote up the lawsuit, and after the woman’s name added, in brackets, “the girl reporter.”

Now I had the files for Silva’s lawsuits against the Times and Mail on the table in front of me. They were frail pieces of dingy cardboard, folded into thirds, filled with papers. Cases would usually have a narrative, where the plaintiff lays out the complaint. A handwritten note on the front of the Mail narrative said the enclosed was a copy of the original, “which is lost from the files.” The narrative for the Times lawsuit was missing entirely. And there wasn’t much else. Before the end of 1889, West was sentenced to prison for overissuing stock certificates of the Times Company. Five years after that, the Chicago Times was defunct. The rest of the legal file was lawyer after lawyer excusing himself from the case.

But tucked inside was a summons for “The Chicago Times Company, James J. West, Joseph R. Dunlop, Florence Noble alias Margaret Noble and ------- Bowen.” On the back, the deputy sheriff scrawled that he had served the summons to the paper, West and Dunlop, but made no mention of Noble or Bowen. It meant, most likely, they couldn’t be found in the county. Florence Noble was gone.

No online searchable newspapers or magazines from the 1880s or 1890s have a reporter named Florence Noble. The archives of the Illinois Women’s Press Association didn’t list any member with that name. No Florence Noble appears in the Chicago directory for those years. The Chicago Medical Society seethed about the exposé at several meetings, but never described the Girl Reporter in any depth. My comparison of her literary quirks to known Chicago journalists didn’t produce a match.

Of course, Florence Noble could also be an alias. Certainly, “Florence” calls to mind Florence Nightingale, a medical heroine. And “Noble” would be an obvious choice. One of the Times’ editorials was headlined, winkingly, “A Noble Work.”

Or the series might have been too scandalous to launch a career. Stunt reporting in general had a dubious reputation, operating at the margins of decency; pretending to be pregnant out of wedlock and seeking an abortion may have been over the line of what a reporter might do and emerge unscathed. Anonymity seems unfortunate in hindsight, but maybe it was essential. Elizabeth Jordan, the New York World reporter, wrote a short story in her collection Tales of the City Room about a respectable young woman lured into writing a “sensational” article by an uncaring editor. Back at the office, male colleagues leered at her. She had to quit and get married to save her reputation.

**********

Even so, by 1896 the World had so many girl stunt reporters its Sunday magazine could barely contain the thrills. “Daring Deeds by the Sunday World’s Intrepid Woman Reporters”: The headline spanned two pages of heart-stopping adventure. Nellie Bly declared she would raise an all-female regiment to fight for Cuba, Dorothy Dare headed out in a pilot ship in a storm, Kate Swan McGuirk rode a horse bareback in the circus. McGuirk, in particular, must have been running on adrenaline. If, under the name “Kate Swan,” she wasn’t leaping overboard to write about rescue crews near Coney Island or seeing what it felt like to be strapped into the electric chair, she was buying opium without a prescription. Every week, a new test of nerve. And in her spare time, she penned more sober articles, often printed on the same page as Swan’s adventures, under the byline “Mrs. McGuirk.”

These features, with lush, half-page illustrations of women facing down dangers, hair and skirts billowing, prefigured nothing so much as comic-book heroines. (See Brenda Starr and Lois Lane.) And as the stakes plummeted and the public good became more difficult to decipher, the reporters were mocked, and the style written off as a fad. Their embrace of writing from a female perspective in female bodies made them all the easier to dismiss as insignificant. Scandalous became silly. The articles ended up as innocuous as those on the women’s page. As a genre, stunt reporting at first offered opportunity for fresh voices and untold stories, but it ended up obscuring originality and individual contributions.

But the contributions were real. Reporters pioneered techniques that would be later hailed by Tom Wolfe in his 1973 manifesto on New Journalism—details of societal status, scene-by-scene construction, dialogue, a distinctive and intimate point of view—the same qualities that make creative nonfiction so wildly popular today. Brooke Kroeger, author of both the survey Undercover Reporting, The Truth about Deception and the definitive biography of Bly, told me that their stunts—not the ones with lion taming and chorus-line dancing, but those that challenged institutions—were “the precursor to full-scale investigative reporting.”

And Florence Noble? Without her identity, her series is less like a novel and more like one of Riis’ photographs. An early experimenter with flash photography, he would barge into a dark tenement room, wake the residents, sprinkle magnesium powder on a frying pan. The circumstances had to be just right: maybe a cub reporter foolishly brave; a newspaper with nothing to lose; an industry reinventing itself; a community of doctors and midwives willing to buck a recent law. Then open the shutter, touch flame to powder and get a burst of illumination.

Related Reads

Sensational: The Hidden History of America's "Girl Stunt Reporters"