Women Resistance Fighters of WWII, the Secret Lives of Ants and Other New Books to Read

These April releases elevate overlooked stories and offer insights on oft-discussed topics

:focal(838x533:839x534)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/77/ee77eb52-70a3-44cd-b18f-1d203dd53b47/booksweek17.png)

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, sparking the beginning of World War II, the leaders of a Warsaw-based chapter of the Zionist HeHalutz youth movement instructed its members to retreat east. Initially, Frumka Płotnicka, a 25-year-old Jewish woman from the Polish city of Pinsk, complied with this request. But as historian Judy Batalion writes in The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler's Ghettos, “[F]leeing a crisis did not suit her, and she immediately asked … [to] leave the area where her family lived and return to Nazi-occupied Warsaw.”

Once back in occupied territory, Płotnicka became a leading member of the Jewish resistance. She brought news of Nazi atrocities to ghettos across Poland, donning disguises and false identities to avoid detection, and was the first to smuggle weapons—guns hidden at the bottom of a large sack of potatoes—into the Warsaw Ghetto. Known for her empathy and gentle demeanor, she earned the nickname “Die Mameh,” or Yiddish for “the mother.”

As the war dragged on, other resistance fighters urged Płotnicka to escape from Nazi-occupied territory so she could bear witness to the “barbarian butchering of the Jews,” in the words of friend Zivia Lubetkin. But she refused, instead opting to stay with her comrades. In August 1943, Płotnicka died at 29 years old while leading an uprising against the Germans as they prepared to liquidate the Będzin Ghetto.

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases, which launched last year to support authors whose work has been overshadowed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, explores the lives of unheralded Jewish women resistance fighters like Płotnicka, poets Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath’s rivalry-turned-friendship, black settlers who sought refuge from Jim Crow in the American West, the millennia-old relationship between music and humans, and the surprisingly complex inner workings of ant colonies.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing–appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler's Ghettos by Judy Batalion

In 2007, Batalion was conducting research on Hungarian resistance paratrooper Hannah Senesh when she came across a musty, well-worn book at the British Library. Titled Freun in di Ghettos—Yiddish for Women in the Ghettos—the 200 sheets of cramped text contained a surprisingly vivid tale: “I’d expected to find dull, hagiographic mourning and vague, Talmudic discussions of female strength and valor,” the author explains in The Light of Days. “But instead—women, sabotage, rifles, disguise, dynamite. I’d discovered a thriller.”

Batalion’s chance find marked the beginning of a 14-year quest to uncover the stories of World War II’s Jewish women resistance fighters. The granddaughter of Holocaust survivors herself, the scholar tells Lilith magazine that she conducted research across Poland, Israel and North America, discovering dozens of obscure memoirs; testimonies; and largely overlooked records of the “hundreds, even thousands, of young Jewish women who smuggled weapons, flung Molotov cocktails, and blew up German supply trains.” Of particular note is The Light of Days’ examination of why these women’s actions are so unrecognized today: Per Publishers Weekly, proposed explanations include “male chauvinism, survivor’s guilt, and the fact that the resistance movement’s military successes were ‘relatively miniscule.’”

At the heart of Batalion’s narrative is Renia Kukiełka, a Polish teenager who acted as an underground courier, moving “grenades, false passports and cash strapped to her body and hidden in her undergarments and shoes,” as the author writes in an adapted excerpt. When Kukiełka was eventually caught by the Gestapo, she retained a sense of fierce defiance, answering an officer who asked, “Don’t you feel it’s a waste to die so young?” with the retort “As long as there are people like you in the world, I don’t want to live.” Through a combination of cunning and luck, Kukiełka managed to escape her captors and make her way to Palestine, where, at just 20 years old, she penned a memoir of her wartime experiences.

The Light of Days, notes Batalion, seeks to “lift [Kukiełka’s] story from the footnotes to the text, unveiling this anonymous Jewish woman who displayed acts of astonishing bravery” while also giving voice to the many other women who took part in resistance efforts. From Niuta Teitelbaum, an assassin who used her youthful appearance to trick Gestapo agents into underestimating her, to Frumka Płotnicka’s younger sister Hantze, a fellow courier and “ebullient charmer” who delivered sermons about “Jewish pride [and] the importance of staying human,” Batalion presents a compelling account of what she deems “the breadth and scope of female courage.”

Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz: The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath & Anne Sexton by Gail Crowther

All too often, writes Gail Crowther in Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz, poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton are defined by their deaths, “portrayed as crazy, suicidal women, an attitude that impressively manages to sweep up sexism and stigma toward mental illness … in one powerful ball of dismissal.” This dual biography seeks to move beyond that one-dimensional, tragic narrative, restoring its subjects’ agency and individuality while celebrating their status as “women who refuse[d] to be silent.” The result, notes Kirkus in its review, is a “sympathetic recounting of the poets’ lives, underscoring their struggles against prevailing images of womanhood.”

Sexton and Plath wielded the written word as an avenue for rebellion. They met in 1959 as students in a poetry workshop, and over post-class martinis shared at the Ritz, they discussed such taboo topics as women’s sexuality, the difficulty of balancing motherhood with their careers and their morbid fascination with mortality. In Sexton’s words, “We talked death with burned-up intensity, both of us drawn to it like moths to an electric light bulb.”

On paper, they had much in common, including childhoods spent in Wellesley, Massachusetts. But Crowther’s descriptions reveal that two had strikingly different dispositions: Whereas Sexton, often outfitted in brightly colored dresses and jewelry, made dramatic late entrances, “dropping books and papers and cigarette stubs while the men in the class jumped to their feet and found her a seat,” Plath was “mostly silent, and often turned up early,” intimidating the other students by making “devastating” comments about their work.

Though they only knew each other for four years before Plath’s suicide in 1963, the pair developed a relationship that, notes Crowther, was “a friendship that would soon evolve into a fierce rivalry, colored by jealousy and respect in equal terms.”

I've Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land by Alaina E. Roberts

In 1887, President Grover Cleveland signed into law the Dawes Severalty Act, which enabled the United States government to break up tribal lands and redistribute them as individual plots. Native Americans who complied with the directive were allowed to become citizens and gain control of 160 acres of farmland per family; those who refused were stripped of both their land and their way of life. Ultimately, the policy resulted in the seizure of more than 90 million acres, the majority of which were sold to non-Native settlers.

As Alaina E. Roberts, a historian at the University of Pittsburgh, argues in her debut book, the Dawes Act transformed Indian Territory, or what is now Oklahoma, into “the ground upon which [multiple groups] sought belonging”—a space where communities could “realize their own visions of freedom.” Each of these groups engaged in settler colonialism, defined by Roberts “as a process that could be wielded by whoever sought to claim land” and “involved … a transformation in thinking about and rhetorical justification of what it means to reside in a place formerly occupied by someone else.”

Members of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes, which were initially exempt from the legislation but fell under its jurisdiction as of 1898, viewed the land as an opportunity to rebuild after decades of violent removals. White Americans, meanwhile, believed that Indian Territory offered “freedom from hierarchical communities that offered them no economic advancement,” writes Roberts. Finally, for formerly enslaved people of African descent, including those enslaved by Native Americans themselves, the prospect of owning land after years in bondage proved especially appealing.

Based on archival research and family history, I’ve Been Here All the While builds on a 2020 journal article by Roberts, whose great-great-grandmother Josie Jackson was an Indian freedperson (a term the author uses to describe black people once owned by members of the Five Tribes) and serves as one of the book’s central figures. Though Jackson and other Indian freedpeople could have moved to other parts of the U.S., “where they [w]ould share in the citizenship and political rights African Americans had just won,” most opted to remain in Indian Territory, where they lacked any clear civic status, as Roberts told the Journal of the Civil War Era last year.

“[F]for some people of African descent, the acquisition of land was more important than the realization of political rights,” Roberts added. “... I believe this is a great case study in the diversity of black historical actors’ definitions of freedom and belonging.”

The Musical Human: A History of Life on Earth by Michael Spitzer

“The deep record of world history has little to tell us about our musical lives,” writes Michael Spitzer, a musicologist at the University of Liverpool in England, for the Financial Times. As he points out, “There are no sound recordings before Edison’s phonograph in 1877, and the earliest decipherable music notation is about 500 B.C.”

Despite this lack of auditory evidence, scholars know that music is far from a modern invention. Long before the arrival of humanity, nature was producing symphonies of its own, including bird songs and whale calls designed “to attract mates, to deter rivals, to create a home and to define who” their creators were, as Spitzer tells BBC Radio 4. Once humans arrived on the scene, they similarly embraced the power of melody, creating such instruments as a 40,000-year-old bone flute and an 18,000-year-old giant conch shell–turned–horn while recording their music-making in art and written records alike.

The Musical Human—a follow-up to last year’s A History of Emotion in Western Music—charts music’s history “from Bach to BTS and back,” per the book’s description. Tracing the development of musical ability to Homo sapiens’ mastery of notes, staff notation and polyphony, all of “which detached music from muscle memory, place and community, and the natural rhythms of speech,” Spitzer explores how varying treatments of these elements influenced musical traditions in different parts of the world, according to Kirkus.

Spanning disciplines, continents and time periods, the musicologist’s ambitious tome makes pit stops everywhere from ancient Greece to Australia, India and the Limpopo province of South Africa. Even balcony jam sessions held during Covid-19 lockdowns make an appearance, refuting what Spitzer, writing for the Financial Times, deems “the fallacy that music [is] a luxury rather than a necessity.” The author concludes, “Music allowed us a triumphal gesture of survival against the virus, and reminds us of our place in the great dance of life.”

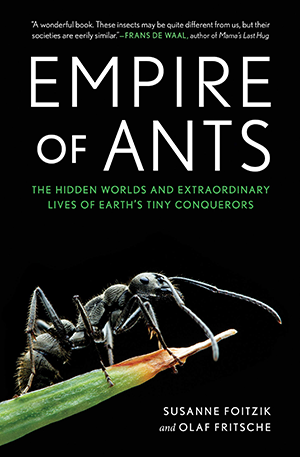

Empire of Ants: The Hidden Worlds and Extraordinary Lives of Earth's Tiny Conquerors by Susanne Foitzik and Olaf Fritsche

No one knows exactly how many ants roam the Earth. But an oft-cited estimate places the insects’ population at around ten quadrillion—in other words, one million ants for every human on the planet. “If all the ants suddenly disappeared, terrestrial ecosystems across the world would be on their knees and it would take a number of years, decades—centuries, even—for them to achieve a new balance,” argue biologist Susanne Foitzik and journalist Olaf Fritsche in Empire of Ants. “Without ants, the natural world would suffer a long period of instability and would never look the same again.”

Comparatively, humans’ disappearance from the face of the Earth might actually be a boon to the planet. Over time, the authors write in the book’s introduction, “nature would recover from our reckless reign, reclaiming towns and cities, producing new species, and returning to the state of biodiversity it boasted just a few thousand years ago.” Given these discrepancies, ask Foitzik and Fritsche, “[W]ho really runs the world?”

The Empire of Ants adopts a similarly playful tone throughout, cycling through factoids about the more than 16,000 ant species on Earth with evident glee. (Foitzik, whose lab specializes in the study of parasitic ants and their hosts, “really, really love ants—even the slave-making kind,” notes Ars Technica in its review.) Split into 13 chapters boasting such titles as “The Path to World Domination” and “Communicative Sensuality,” the book spotlights such insects as Eciton burchellii, a type of army ant whose hours-long raids result in the deaths of upward of 100,000 victims; Dorylus wilverthi, whose queen ants are roughly the size of a small mouse; and Paraponera clavata, a South American bullet ant whose bite has been likened to being shot.

Ants, according to the book’s description, are more like humans than one might think: “Just like us, ants grow crops, raise livestock, tend their young and infirm, and make vaccines. And, just like us, ants have a dark side: They wage war, despoil environments, and enslave rivals—but also rebel against their oppressors.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)