Would You Pass the Panic-Proof Test?

If an atomic bomb drops on your house, a civil defense official advises: “Get over it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201111090110121953-aug-21-colliers-panic-470x251.jpg)

American futurism of the 1950s wasn’t filled with just flying cars and jetpacks. There was also an overwhelming fear that nuclear war could break out between the United States and the Soviet Union. The August 21, 1953 issue of Collier’s magazine included an article by U.S. Civil Defense Administrator Val Peterson titled “Panic: The Ultimate Weapon?”

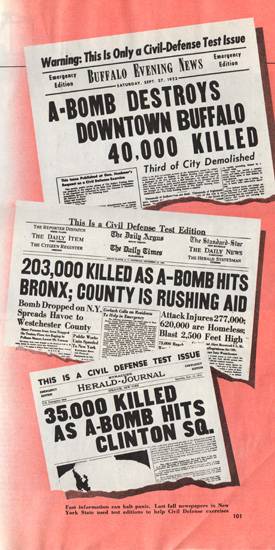

Fictional headlines of New York's destruction

Blaring fake headlines—such as “A-BOMB DESTROYS DOWNTOWN BUFFALO 40,000 KILLED” and “203,000 KILLED AS A-BOMB HITS BRONX; COUNTY IS RUSHING AID” and “35,000 KILLED AS A-BOMB HITS CLINTON SQ.”—the article counsels readers that something catastrophic is bound to happen, but when it does you must keep your wits about you for the good of your country.

With a heavy focus on the problems presented by widespread panic, Peterson’s article is a horrifying glimpse at a futuristic world of death and destruction; inescapable, even from Main Street, U.S.A.:

You have just lived through the most terrifying experience of your life. An enemy A-bomb has burst 2,000 feet above Main Street. Everything around you that was familiar has vanished or changed. The heart of your community is a smoke-filled desolation rimmed by fires. Your own street is a clutter of rubble and collapsed buildings. Trapped in the ruins are the dead and wounded — people you know, people close to you. Around you, other survivors are gathering, dazed, grief-stricken, frantic, bewildered.

What will you do — not later, but right then and there? On your actions may depend not only your life and the lives of countless others, but your country’s victory or defeat, and the survival of everything you hold dear.

Ninety per cent of all emergency measures after an atomic blast will depend on the prevention of panic among the survivors in the first 90 seconds. Like the A-bomb, panic is fissionable. It can produce a chain reaction more deeply destructive than any explosive known.

If there is an ultimate weapon, it may well be mass panic. Mass panic — not the A-bomb — may well be the easiest way to win a battle, the cheapest way to win a war. That’s why military leaders so strongly emphasize individual and group discipline. At the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., a small force of Athenians routed the powerful Persian army — after it panicked. In our own Civil War many battles were decided when inexperienced troops suddenly broke and fled. Hitler, in 1938, created a special staff to cope with this invisible but ever-threatening sixth column. In 1940, the shock wave of panic caused by Nazi Panzer blows and fifth column activities hastened the collapse of France.

War is no longer confined to the battlefield. Every city is a potential battleground, every citizen a target. There are no safe areas. Panic on Main Street can be as decisive as panic in the front lines. Just as a single match can burn a dry forest, so a trivial incident can set off a monstrous disaster when the confusion and uneasiness of the population have reached tinder point.

“Every city is a potential battleground, every citizen a target. There are no safe areas.” There’s something about reading the bleak assessment of a government official charged with protecting the United States against nuclear attack that helps put all of the fear and paranoia of the Cold War into context. It’s hard not to think that the world is going to end when the government is quite literally telling you that you’re a target and nowhere is safe.

The piece even offers a more geographically specific, “Preview of Disaster in Manhattan.” It was surprisingly common for Collier’s to imagine the destruction of New York City in the early 1950s. Just three years before this article was published, famed illustrator Chesley Bonestell did a cover for the August 5, 1950 issue of Collier’s with a gigantic mushroom cloud over Manhattan — the words, “HIROSHIMA, U.S.A.: Can Anything Be Done About It?” asking readers to consider the complete destruction of America’s largest city. Peterson’s 1953 article even makes comparisons to Hiroshima and how such a scenario might play out in New York City. For the October 27 1951 issue of Collier’s, Bonestell again illustrated what a hydrogen bomb would look like over lower Manhattan. This time, however, he included bombs over Moscow and Washington, D.C.— but decimated New York was certainly a perennial favorite of Collier’s.

Peterson offers a vivid description of what might happen if a post-atomic bomb panic were to strike New York City :

Most strategic targets in the United States lie in heavily populated areas. The industrial and business centers of such cities are crowded by day and in some metropolitan areas only staggered lunch hours and working periods permit the orderly evacuation of buildings. If all the office buildings in the downtown financial district of Manhattan were emptied suddenly, as in a panic, some people estimate the narrow streets would be several feet deep in humanity.

Suppose such an emergency were compounded by enemy-inspired rumors. Word of possible safety in Battery Park could bring such a concentration of people to the tip of Manhattan Island that thousands would be pushed into the harbor to drown. At Hiroshima, 1,600 died when they took refuge in a park along the river and were forced into the water by new thousands crowding into the area.

The consequences of an uncontrolled mass stampede from such a population center as Manhattan are almost incalculable. Even if the four underwater traffic tunnels and the six major bridges leading from the island were left undamaged by an attack, disorganized traffic could soon bottle many of the avenues of escape. Those who did succeed in fleeing the island would pour into adjacent areas to become a hungry, pillaging mob — disrupting disaster relief, overwhelming local police and spreading panic in a widening arc. True, New York City presents a civil defense problem of unusual dimensions, but similar hazards face every city in the land under possible attack.

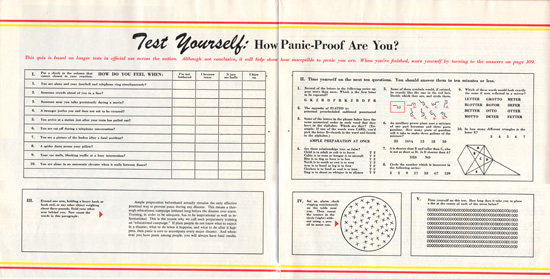

The article included a huge self test to determine how “panic-proof” you are. On a scale of “I’m not bothered” to “I blow up” the test asked things like how you feel when you’re alone and your doorbell and telephone ring simultaneously or how you feel when you see a picture of bodies after a fatal accident.

"Test Yourself: How Panic-Proof Are You?"

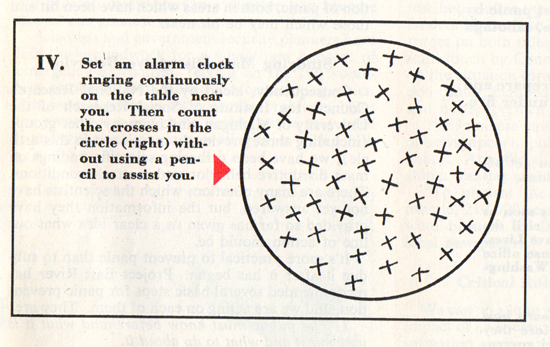

This test reads like it was designed by an insane guidance counselor. Question four says to “set an alarm clock ringing continuously on a table near you. Then count the crosses in the circle (right) without using a pencil to assist you.”

"Set an alarm clock ringing continuously on the table near you..."

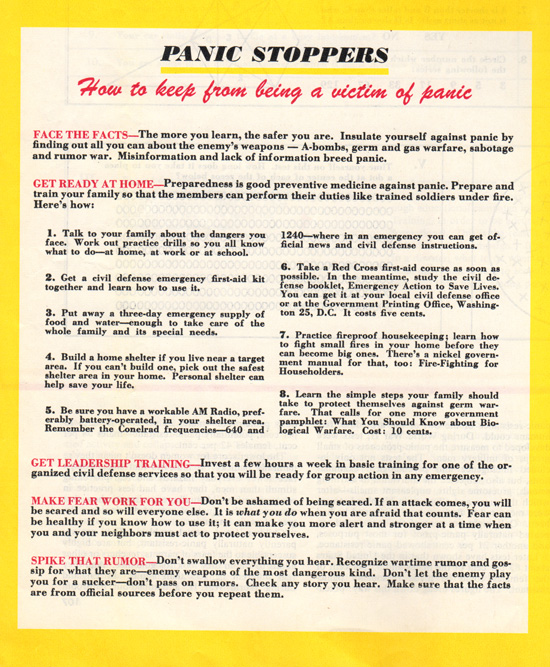

The piece also included a handy guide called “Panic Stoppers: How to keep from being a victim of panic.” Citizens are encouraged to buy a battery-powered AM radio, keep a three-day emergency supply of food and water, and even build a home bomb shelter. It’s quite interesting that one of the first tips is encouraging people to insulate themselves against panic by learning about “the enemy’s weapons – A-bombs, germ and gas warfare, sabotage and rumor war.”

"Panic Stoppers: How to keep from being a victim of panic"

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)