After 39 Years of Wrongful Imprisonment, Ricky Jackson Is Finally Free

Locked up for a murder he didn’t commit, he served the longest sentence of any U.S. inmate found to be innocent

“I feel such a sense of urgency these days. Because I know exactly how much time they took away from me.”

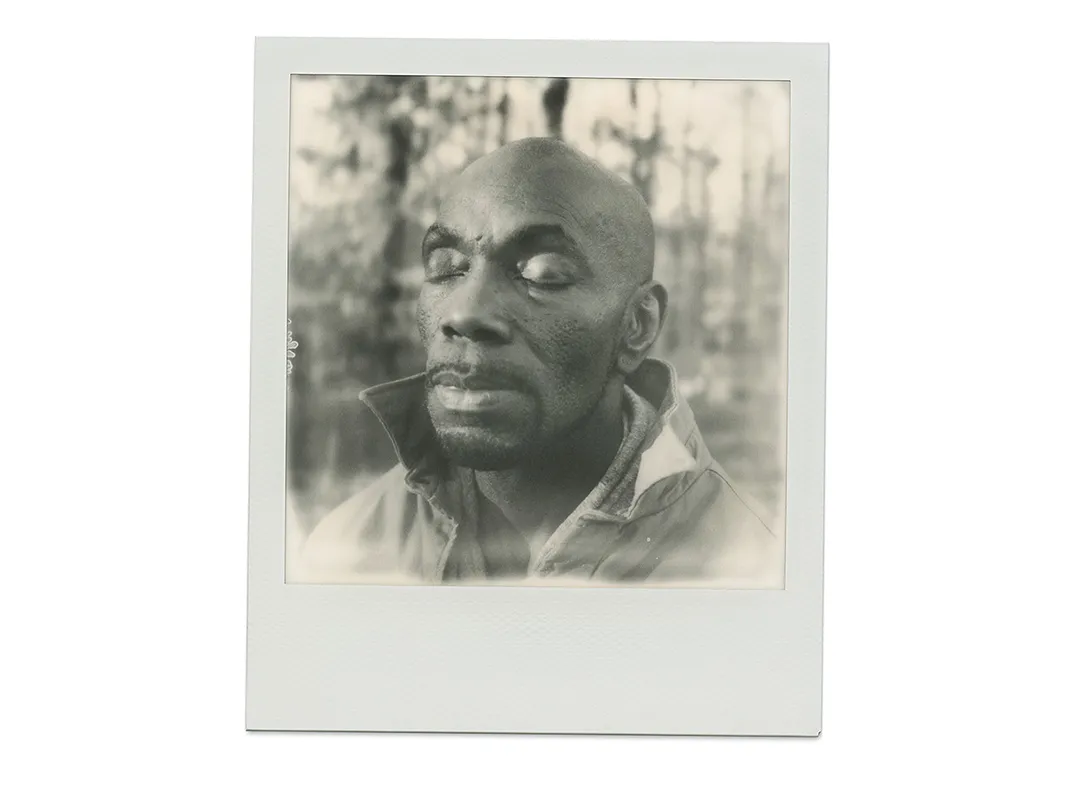

Ricky Jackson, 59, is sprawled across a leather couch in the basement of his new house in Chesterland, Ohio, some 20 miles east of Cleveland. His Nike-clad feet are propped on the end table. An Apple iPhone rests on his chest. There are framed portraits of Bob Marley, flags commemorating the Cleveland Cavaliers’ 2016 NBA championship and numerous books, including stories by J.G. Ballard and one about ancient Egyptian mythology. A small bar. A neon sign blinks “man cave.”

“I intend to live well,” Jackson continues, pouring himself a glass of pomegranate juice. “But it has nothing to do with whether I’m here in this nice house, or whether I’m homeless. It has to do with attitude. I’ve been given an opportunity, you understand? And I’m not going to waste it by holding grudges.”

Not that anyone would blame him. Beginning at age 18, Jackson spent 39 years in an Ohio prison for a crime he didn’t commit—the longest prison term for an exonerated defendant in American history, and a staggering example of how the criminal justice system can wrong the innocent.

Jackson, who is short and lean, with a creased forehead and pitted cheeks, grew up on Cleveland’s East Side, the first son of a large working-class family. At 18, he enlisted in the Marines, hoping to make a career of it, but within a year was granted an honorable discharge for a balky back. Soon after returning home he and two friends were arrested for killing Harold Franks outside a neighborhood convenience store. Franks was doing business there—he sold money orders—when, according to police, a pair of assailants splashed acid on his face, clubbed him, shot him several times, stole about $425 and fled.

Police never found the murder weapon, and Jackson and his friends, the brothers Wiley and Ronnie Bridgeman, insisted they were elsewhere at the time of the shooting and had never laid eyes on Franks. But detectives had obtained a statement from a local paperboy, 12-year-old Eddie Vernon, who knew the Bridgemans and Jackson. Eddie told police that Jackson fired the handgun, Ronnie Bridgeman doused the victim with acid and his brother drove the getaway car. Though Eddie was a shaky witness—he failed to identify the suspects in a police lineup, and several of his classmates testified he had not been near the crime scene—three separate juries accepted the youngster’s account. In 1975, Jackson and the Bridgemans were convicted of murder and sentenced to die by electric chair.

“The boy I was before prison, with all his dreams, all his intentions, he died the moment I was locked up,” Jackson remembers.

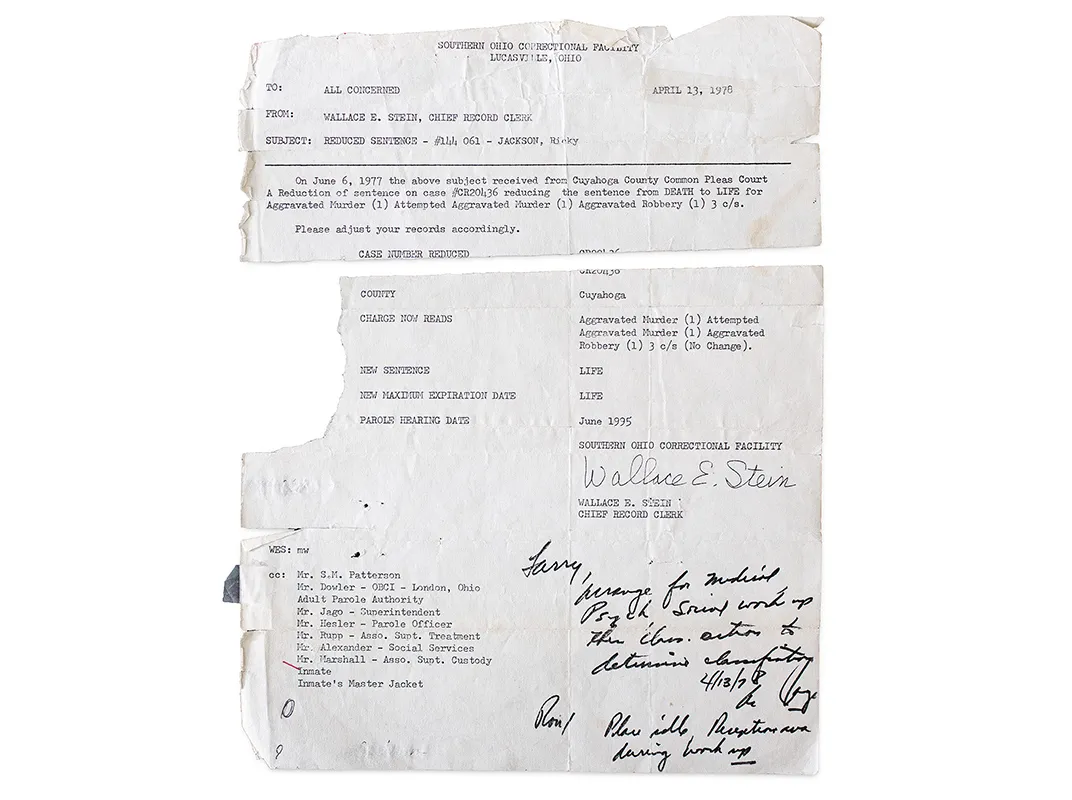

On death row, in a narrow cell with a slot for a window, he was unnerved by the realization that people wanted him to die. Then, in 1977, his death sentence was reduced to life in prison because of a technicality, and the following year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Ohio’s capital punishment law was unconstitutional. Jackson joined the regular population at Southern Ohio Correctional Facility.

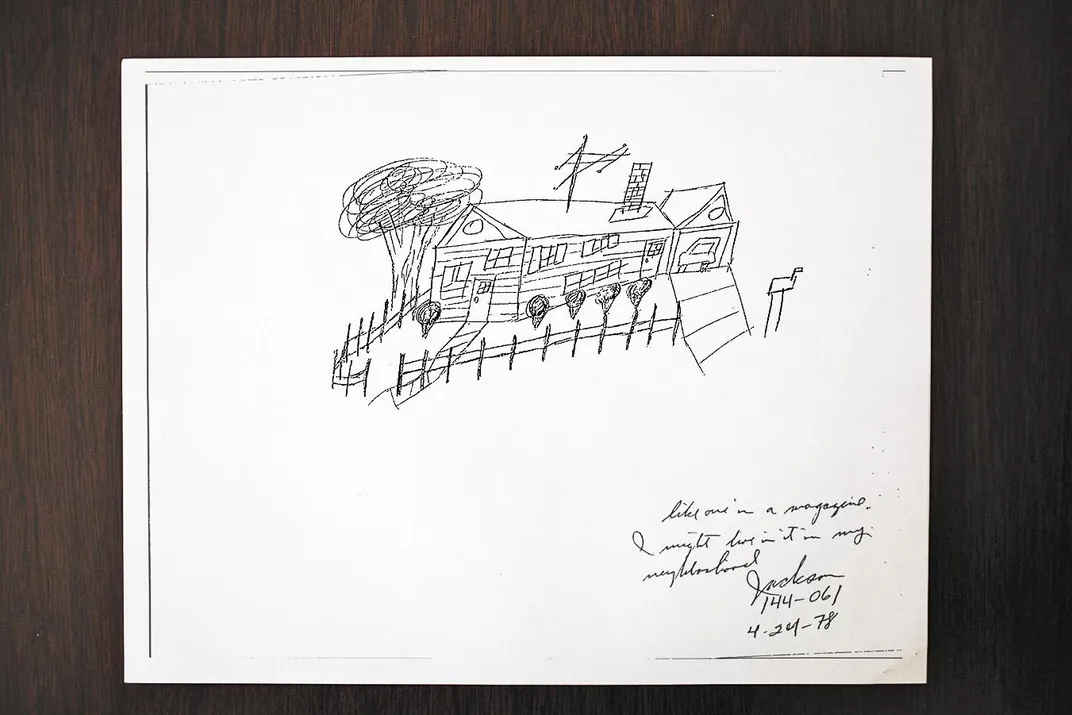

Prison shaped the adult just as the streets of East Cleveland had shaped the kid. He fought other inmates when he had to, and spent months at a time in solitary confinement. He’s not a religious man, but even in his “darkest moments,” he says, “I had this ember inside me, some little smoldering piece of hope. I’d say, If I give up, what am I really surrendering to? And so you go on.” He studied gardening. He refereed basketball games. He found solace in the prison library, often reading a book a day—biology, nature, history—losing himself in those other worlds. And he wrote letters—to journalists, filmmakers, anyone who might be interested in his case. In 2011, The Scene, a Cleveland magazine, published an article about the frail nature of Jackson’s conviction and the implausibility of the testimony that had condemned him. Among the readers was Eddie Vernon’s pastor, who arranged a meeting between Vernon and lawyers with the Ohio Innocence Project. Vernon rescinded his 1975 testimony, saying police coerced him into fingering Jackson and the Bridgemans. In 2014, prosecutors dismissed charges against the three men.

Ronnie Bridgeman, now Kwame Ajamu, had been paroled in 2003. Wiley had been paroled in 2002 but was reincarcerated three months later following a parole violation. Jackson, who had passed up several chances to shorten his sentence by admitting a role in the Franks killing, was released after spending four decades, his entire adult life, behind bars.

“It was overwhelming, being out after all that time,” Jackson says. “I just did my best to stay grounded. To get the little things done: get a driver’s license, find an apartment.” He bought a used car, started a business with friends refurbishing houses around Cleveland. When settlement money came in from the state—nearly a million dollars—he bought the new house, for himself and his fiancée, whom he met through his niece.

He is still getting used to his “rebirth,” he calls it. He tries to keep busy, traveling to construction sites, speaking at conferences and other events about his time in prison. He’s planning trips to Ireland and Jamaica. In the evenings, he reads, or helps his fiancée’s three kids with their homework. And he stays in touch with the Bridgeman brothers, friends who understand what he’s been through.

Eddie Vernon met with Jackson and the Bridgemans after their exonerations and apologized for implicating them. Jackson forgives him. “He was just this goofy little kid who told a whopper,” Jackson says. Besides, “it wasn’t only [Vernon] that put us there. It was the lawyers, the police, the whole broken system. And there are a lot of innocent men out there who are never going to get justice. In that sense, I feel lucky.”

Related Reads

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption