In June of 1940, as war swept across Europe, thousands of Red Army troops arrived at the eastern border of Lithuania, making good on a secret pact with Germany to divvy up the continent. Local leaders were given an ultimatum: Agree to immediate annexation by the Soviet Union, or face a long and bloody invasion. Overmatched, the government capitulated, and within days the Soviets had seized control of the country. In Kaunas, the home of the former president, Red Army tanks clogged the streets; in Vilnius, dissenters were hunted down and arrested or killed.

In August, in a wood-framed house in northeastern Lithuania, a young Jewish writer named Matilda Olkin unlocked her diary and began to write:

I see—crowds falling to their knees,

I hear—nights filled with crying.

I travel through the world

And I dream this strange dream.

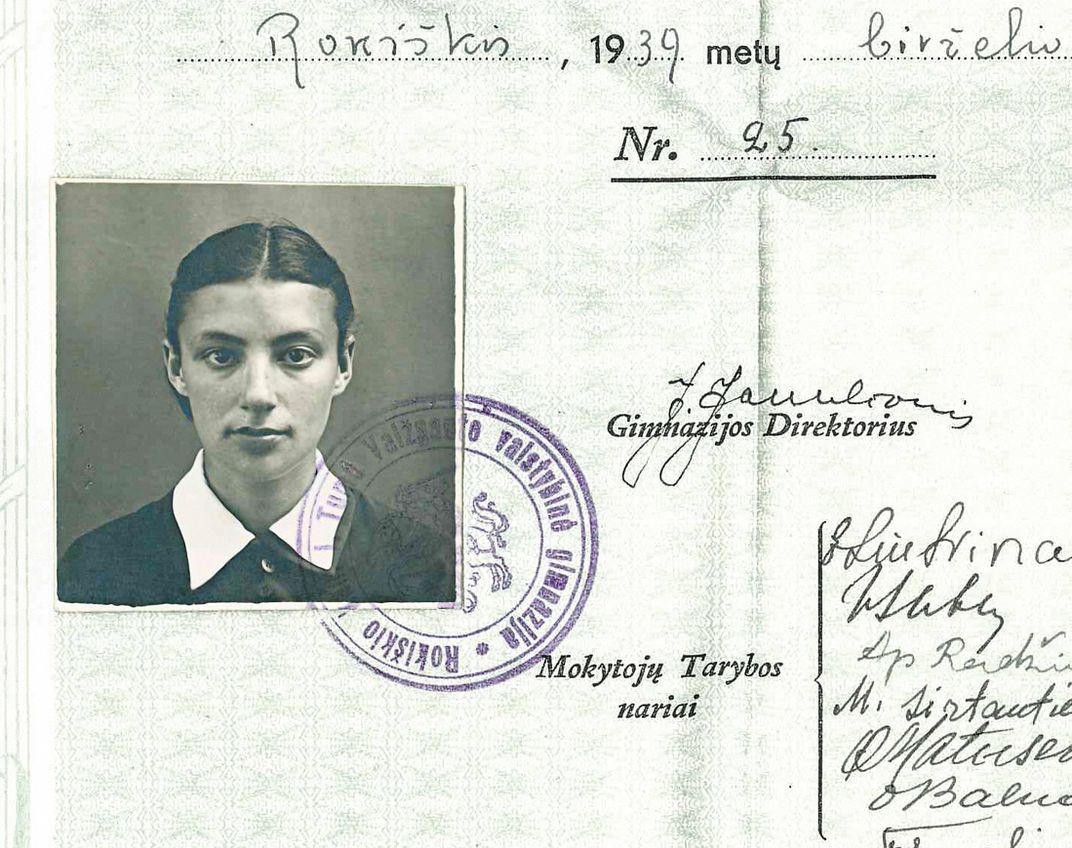

The poem, describing the pilgrimage of an “exhausted” people across a hellscape of “burning sands,” was a departure for Olkin, then just 18. Slight and brown-haired, with opaline skin and wide-set brown eyes, Olkin had grown up in the farming village of Panemunelis, in circumstances she recalled as idyllic. Her father, Noah Olkin, ran the town pharmacy; her mother, Asna, stayed home with Matilda and her three siblings—an older brother named Ilya, and two little sisters, Mika and Grunia.

Like much of the country, Panemunelis and the nearby city of Rokiskis were home to sizable populations of Jews, who worshiped freely and held important civic positions. Every Sunday, Noah Olkin dropped in on Juozapas Matelionis, the village priest, to discuss literature and theology over tea. Matilda and her two younger sisters frequently ate meals with the Catholic girls next door. Together the girls wandered the birch forests and undulating pastures that surrounded Panemunelis.

Matilda’s early surviving work pays homage to that pastoral beauty. The writing is vivid and sweet, full of encomiums to “rejoicing” flowers, “leaping” suns and “silver stars.” A poem called “Good Morning” practically overflows with exuberance:

But the Sun shines most

In the eyes of the little girl.

Her eyes are bright, full of light.

They greet her joyful world,

A world bursting to life and filled with sunshine.

“Good morning! Good morning!”

Soon Matilda was publishing verse in literary journals, and editors hounded her with solicitations. (“We are waiting and waiting for the fruits of your cheerful pen,” one wrote.)

But in time Matilda’s poetry darkened, and she became “distant”: “She would stand and gaze out the classroom window with her hands tucked under her apron,” a friend later said. “What she was thinking, I don’t know.”

A diary Matilda started keeping in August 1940 offers some clues. “Times are awful,” she wrote in one entry. “The world has spilled out into the streets.” In another, she wrote, “There are more and always more worries. Good always follows bad. And so where is the good?”

The roots of her anxiety were both personal and political. Although her brother had thrown his support to the new Soviet regime—“Ilya,” Matilda noted acidly, “is one of those enlightened people who believes in communism”—Matilda was more mistrustful. And presciently so: Her father’s pharmacy was nationalized, and his income all but erased. He and Matilda’s mother were thrown into profound despair. “They are both ill and unhappy people,” Matilda wrote. “And I am their daughter, but I can’t do anything to help them. I can’t help Papa, who complains of a bad pain in his stomach, or Mama, who recently began blowing through her lips in this strange manner.”

In the major cities, a far-right Lithuanian group called Iron Wolf was urging a boycott of Jewish businesses; anti-Semitic leaflets were distributed in the streets; and at least one leading newspaper railed against the “dirty habits of the Jews.” It must have felt that chaos was inevitably coming for Matilda and her family, too.

Still, that October, Matilda left for Vilnius to study literature. She did not do so lightly. “I am constantly saying goodbye, goodbye,” she wrote in her diary. But the university was offering a stipend, enough to help support her family, and she felt she had no choice.

Besides, cosmopolitan Vilnius suited her. She went to the opera, listened to “nervous screeching music” at a bar, danced at clubs, and got a perm. And she pined after an on-again, off-again boyfriend. In her diary, she scolded herself for fixating on relatively trifling romantic concerns: “People are starving. The war is moving closer toward us. I may not receive my stipend—nothing is certain, everything is in a fog. And I am standing on the edge of a precipice, picking at the petals of a daisy, asking: ‘Loves me? Loves me not.’”

In what may be her last poem, dated November 14, 1940, the setting is a funeral. The narrator peers back at the throngs of mourners:

Oh, how many have gathered

And no one will see love.

I hold an infant in my arms—

And my infant—is Death.

Seven months later, Hitler invaded Lithuania. Violating the pact with the Soviets, the Germans chased out the Red Army in days. On June 26, they reached Kupiskis, miles from Panemunelis.

If latent anti-Semitism in Lithuania was the tinder, the Nazis were the spark. The Germans were quick to point to Jews as the cause of Lithuanian “humiliation and suffering under Soviet rule,” as the Holocaust historian Timothy Snyder has written, and the Nazis instructed their local collaborators to round up Jewish families into walled ghettos for “processing.” Soon word reached Matilda in Vilnius: Her parents and sisters had been arrested.

We have no record of Matilda’s thoughts on her journey home, because by the end of February 1941 she had stopped writing in her diary. Why she did so is unknown: Perhaps she switched to a different journal, although there were plenty of pages left in the original. More likely, circumstances prevented it. The once-faraway war the young poet had tracked through newspaper headlines was now on her doorstep, and everything she held dear was about to be destroyed.

Chapter Two

Eleven years ago, in the summer of 2007, a Lithuanian historian and museum curator named Violeta Alekniene received an email from an editor at Versmes, a publishing house. Versmes was working on a series of monographs about the Lithuanian provinces, from the Middle Ages to the present, and the editor hoped Alekniene would write about Panemunelis during the Second World War.

Alekniene, then in her early 50s, immediately agreed. She had grown up in Panemunelis, as had her parents and grandparents. She’d lived through the stifling postwar Soviet occupation, when the country was part of the USSR, and the heady early years of independence, in the 1990s. She knew the place intimately, and, moreover, she had long wanted to write about a grim part of Lithuania’s history: the extermination, by the Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators, of more than 200,000 Lithuanian Jews—some 95 percent of the country’s Jewish population.

As Alekniene explained to me this past summer, she knew from previous research the broad outlines of what had happened to the Jews of her home district: Shortly after the Nazis appeared, the entire Jewish population was corralled into the village’s train station and sent to the nearby town of Rokiskis. There, in August 1941, more than 3,200 men, women and children were lined up in front of hastily dug pits and shot.

But not all the Jews of Panemunelis had perished in those pits: Three families—merchant families who were thought to have hidden wealth—were moved to a stable not far from Father Matelionis’ church. The Olkins, who had once lived a few miles from the house where Alekniene grew up, were among them. Alekniene decided it would be part of her mission to track down the details of their fate.

“Outside of raising my family, my entire life has been dedicated to historical research,” Alekniene told me. “To not write about this tragedy now that Lithuania was independent, now that we had freedom of speech, would have been”—she paused. “I had to do it.”

Alekniene threw herself into the research. She dug through pre- and postwar Soviet archives, and interviewed dozens of subjects from the region. And she devoured Matilda’s diary, which was published around that time in a local journal. From these sources she learned about the Olkins and their personal lives, and she traced Matilda’s growing fame as a young poet. Matilda’s writing made a permament impression. Eventually, she came to view Matilda as a symbol of the goodness and beauty that had been lost in the Holocaust. From this tragedy, she hoped to tell the story of the near-erasure of Lithuania’s Jewish community. “Matilda had a special voice,” Alekniene told me. “To me, it was a voice that needed saving.”

In 2008, Alekniene tracked down a childhood friend of Matilda’s named Juozas Vaicionis. He told her that after the rest of the Jews had been deported, the Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators—known as “white armbanders” for the sashes they tied under their shoulders—ordered Matilda to clean the now-empty train station. Vaicionis sneaked into the station to see Matilda and offered to hide her or find her safe passage out of Panemunelis. “Matilda would not even answer me,” Vaicionis recalled. “She kept on scrubbing the floors. I could not get her to answer me when I insisted, ‘Why don’t you want to run away from here?’” But Matilda was adamant: She would not abandon her family.

Alekniene could find only one surviving witness to describe the brutal end of the Olkins’ ordeal. Her name was Aldona Dranseikiene. One July morning in 1941, she told Alekniene, she was with her father when they spotted a horse-drawn cart hammering down the dirt road that led north out of Panemunelis. Up front sat men in white armbands; escorts carrying rifles pedaled on bicycles alongside them. The procession drew to a halt in a pasture. Dranseikiene, then 8-years-old, took cover behind a haystack, while her father craned his neck over the stack to watch.

“They shoved their guns into the backs of the men and the women who had been blindfolded and forced them out of the wagon,” Dranseikiene told Alekniene. (Dranseikiene, like all the eyewitnesses, has since died.) “They made them walk up to the top of the hill,” she went on. “We heard screams and cries. That went on for a very long time. Who knows what went on there? Only much later, in the afternoon, we heard their final death cries and gunshots.”

In the evening, the killers showed up drunk at nearby farms, demanding vodka. “For a long time,” Dranseikiene recalled, “those men hung around and sang.”

The next day, local farmers made their way across the pasture, where they found, beneath a thin layer of dirt, five twisted corpses—Noah, Asna, Matilda, Grunia and Mika Olkin—lying beside four others, members of another Jewish family, the Jaffes. (The fate of the third family remains unknown.) The farmers covered the shallow grave with more dirt and sprinkled it with lime, to aid decomposition and prevent forest animals from desecrating the corpses. (Matilda’s brother, Ilya Olkin, who had been living in the city of Kaunas, would join the resistance, but was killed not long afterward.)

I asked Alekniene if she knew what happened to the Olkins’ Lithuanian killers. One, she said, was tried and executed in the Soviet era; another went mad. Two reportedly made their way to America. But the other two remained in the village. “No one could definitely prove it was them, but naturally there were whispers,” Alekniene told me. “I was raised with their children, in fact.”

I wondered if the children had been ostracized. Alekniene shook her head. “They are very good people,” she told me. She was eager to move on.

Chapter Three

In piecing together the Olkin family’s last days, Violeta Alekniene was, in essence, continuing the narrative that Matilda Olkin had begun in her diary. This summer, an elderly scholar named Irena Veisaite invited me to see the document myself.

Her apartment in Vilnius was high-ceilinged and bright, the walls covered with books, watercolors and family portraits. Opening the door, Veisaite complained of the persistent headaches and fatigue that often kept her inside. “But that’s all right,” she smiled, her eyes magnified behind wire-framed glasses. “It means the young people have to come to me.”

I followed her to an office and waited as she rummaged through the bottom shelf of a large armoire. She returned with two books. The thicker one was bound in hand-tooled leather: Matilda’s diary. The other, which had an ink-stained cardboard cover and appeared to be a repurposed ledger, held Matilda’s poems. I ran my finger over the handwritten script. M. Olkinaite, it read—a formal Lithuanian language rendering of Matilda’s family name.

In the 1970s, Veisaite explained, she was working as a tutor at the University of Vilnius when one day a graduate student stopped by with a pair of tattered books. The student—his name was Alfredas Andrijauskas—came from Panemunelis, where as an organist at the church he’d known Father Matelionis, the priest who had been close to the Olkins.

He told a poignant story: Father Matelionis had offered to hide Noah Olkin and his family, but Olkin had refused, fearing that anybody caught harboring Jews would be shot. Instead, he passed along Matilda’s notebooks, which Father Matelionis then stashed inside a hidden compartment in the altar of his church. In the 1950s, the Soviets deported Father Matelionis to Siberia, part of a campaign of religious persecution across the USSR. But just before he was sent away, he gave the documents to Andrijauskas. Now Andrijauskas was bringing them to Veisaite.

Veisaite, a rare Jewish Lithuanian Holocaust survivor who chose to remain in the country of her birth after the war, read the poems first, in a single sitting. “I was crying,” she told me. “I thought, ‘Why am I alive and Matilda is dead?’”

Veisaite immediately grasped the importance of Matilda’s writing, which gave voice to the dead in a way that forensic accountings of the Holocaust could not. Soon afterward, Veisaite published an essay about Matilda’s poetry in a literary journal. She longed to dig deeper into Matilda’s life and the circumstances of her death, but she could only say so much: The killing of Jews had never fit comfortably with the Soviet narrative of the war, which framed it in Manichaean terms—fascists on one side, resisters on the other. Nor did it mesh with the post-Soviet Lithuanian narrative that resolutely turned its gaze from local complicity in the murder of the country’s Jews.

Veisaite did eventually publish and speak extensively about the Holocaust. But for three decades, Matilda’s notebooks remained in the armoire, as Veisaite waited for the right opportunity. “Somehow,” she smiled, “I think it is fate that they came to me.”

I understood what she meant—the notebooks, the irreplaceable insight they gave into a life, at once ordinary and tragic, and the story of those who had cared for them, had the improbable arc of a legend. It sounded fantastical that they survived, but it was true. The evidence was in front of me.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/81/3e81e4e5-4b57-4d5e-9563-abb4486af77c/lith-dip.jpg)

Chapter Four

From Vilnius, it’s a three-hour drive to Panemunelis, ending on two-lane roads no more than 15 feet across. The morning I made the drive, storks gathered on the roadside in perches constructed from truck tires and discarded lumber. In Lithuania, the birds are considered to be a sign of harmony and prosperity, and locals do what they can to get them to stick around.

I arrived in Panemunelis around midday. The skies were cloudless, and the temperature close to 90, but a breeze was blowing across the fields, bringing with it the scent of ryegrass and of the heavy rains forecast for later that afternoon. I recalled Matilda’s description of a violent storm in the late summer of 1940:

Suddenly it became so dark that it seemed as though someone had drawn the curtains closed across the windows....I ran outside and the wind was so strong that it almost knocked me down onto the ground. I adore storms. I push my chest out into the wind and set my eyes on the fields. And then I feel that I am alive and that I am walking forward.

Today Panemunelis is still a farming village, home to no more than a few hundred people. There is a general store, a town square and a dozen tangled streets, unspooling through the surrounding farmland like a ribbon. In a gazebo near the post office, three old men had gathered to drink brandy; in front of a warehouse, a German shepherd strained at the end of a chain.

The town’s train station is still standing, but it was dark, its windows bricked over. I found the Olkins’ address easily enough—the family lived directly across from the local mill—but their home had reportedly burned down years ago. I knocked at the nearest house. The curtains parted; no one answered.

“I know their story—we all know their story,” Father Eimantas Novikas told me that afternoon, standing in the nave of the village church. Novikas, who was transferred to Panemunelis three years ago, is immense, more than six and a half feet tall, with a formidable belly—in his black cassock, he resembled a bell. I followed him out to the churchyard. Through the foliage, we could see the stable that had housed the Olkins and other families in their final days. “What happened was a tragedy,” Novikas said. “What I hope is that we can continue to learn about the”—he looked at me pointedly—“events, so they can never happen here again.”

And yet a full reckoning with Lithuania’s role in the Holocaust has been a decidedly long time coming, not least because of the Soviet occupation, which made the self-examination undertaken elsewhere in Europe—the scholarship, the government-appointed commissions, the museums and memorials—more difficult. Even after independence, local historians acknowledged the atrocities but placed the blame mainly on the Nazi occupiers. Lithuanian collaborators were written off as drunks and criminals. This was something I heard often. The killers may have been our countrymen, but they were nothing like us.

As a coping mechanism, the rhetoric isn’t difficult to understand. But it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. “Genocide cannot be accomplished by lowlifes and social rejects,” the Lithuanian scholar Saulius Suziedelis said in an interview last year. “It requires an administrative structure. Who ordered the towns in the countryside to set up small ghettos? Local officials. So I would say the number of participants is much larger than we’d like to admit.”

When Violeta Alekniene finally published her essay about the Olkins, in 2011, the country was just beginning to revisit the inherited Soviet narratives with a measure of critical distance. By 2015, the climate was ripe for a more forceful intervention. That year, the best-selling Lithuanian journalist Ruta Vanagaite published a book titled Us: Travels With the Enemy, a rigorously researched account of local complicity in the mass murder Lithuanians committed against their Jewish neighbors across every sector of society—civil servants, academics, the military. The titular “us” refers to those who Lithuanian society pretends are not really Lithuanian: on the one hand, murdered Jews, and on the other, their Lithuanian executioners.

In interviews, Vanagaite urged Lithuanians to be honest about their history. “Go and look,” she said. “What about the things we have at home—antique watches and antique furniture. Where did they come from? We need to ask where the gold in the teeth of our grandmothers came from. We have to ask questions—we owe it to the victims of the Holocaust.”

Around that time, a young playwright in the city of Rokiskis named Neringa Daniene was casting about for a new project when she learned of the story of the Olkins. Like Vanagaite, whose book she later read, Daniene firmly believed the Holocaust could no longer be shunted aside. “I thought it could really change people’s hearts to hear a story like Matilda’s,” Daniene told me. She resolved to write a play about the poet, based on Alekniene’s essay; to prepare, she arranged to bring copies of Matilda’s poems and her diary with her on a family vacation. “Every day, my children would go swim in the lake, and I’d just lie on the grass, reading the diary and sobbing,” she recalled.

The Silenced Muses premiered in Rokiskis in November 2016. The first performance was sold out, as was each date in the initial run. Daniene and her troupe took the play on the road. “Every time, it was just as emotional as the first time,” she said. Still, Daniene was determined that the play focus more on Matilda’s life than her death—the murders take place offstage.

On the advice of a friend, a Lithuanian-American poet and translator named Laima Vince saw the play. “For many years I believed that the Lithuanians who murdered their Jewish neighbors were used by the Nazis, perhaps even forced at gunpoint to commit these crimes,” Vince later wrote on a website called Deep Baltic. “That was the story I’d been told. Perhaps I comforted myself with this thought because the truth was too horrific to face.”

Vince became immersed in Matilda’s life and work, and set about translating Matilda’s collected writing into English. “The play was popular in Lithuania, but once Matilda’s writing is translated, and can be accessed by the whole world, my hope is that the number of people who are moved by her story will grow,” Vince told me.

Already, Matilda’s poetry has been included in a grade school textbook published by the Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore. And Irena Veisaite, the scholar, recently announced plans to donate the notebooks to the institute, which plans to release a dual-language edition of Matilda’s poetry, in Lithuanian and English. An annotated version of the diary will follow—part of a larger effort by local institutions to incorporate Jewish voices into the national canon.

Another artist inspired by The Silenced Muses was a local woodcarver, who erected a totem to Matilda in a median near the site of her childhood home. Hewn out of oak, the memorial was engraved with birds and lilies, which are recurring motifs in Matilda’s poetry, and a Star of David; etched near the base is a stanza of her verse:

Then, someone carried off

The Sun and all the flowers.

The young sisters left

For foreign lands.

Chapter Five

Last summer, a more formal memorial went up next to the gravel road that bisects the pasture where the Olkin and Jaffe families were killed. The memorial was funded largely by donations from Lithuanians familiar with The Silenced Muses. The granite gravestone is engraved with the names of the Olkin and Jaffe families in Hebrew and Lithuanian.

And in the coming months, the Rokiskis history museum will mount a permanent exhibition devoted to Matilda and her family. The museum has also been keen to identify the precise spot where the Olkins and Jaffes were buried. Some researchers said the grave is at the corner of the pasture; other testimony placed it midway down the field’s western flank. Earlier this year, the museum’s director contacted Richard Freund, an American archaeologist, who planned to be in Lithuania excavating the Great Synagogue in Vilnius, and asked if he would take a look.

In July, I accompanied Freund, of the University of Hartford, and two geoscientists, Harry Jol, from the University of Wisconsin, and Philip Reeder, from Duquesne University, to find Matilda’s final resting place. In recent years, the three men and their colleagues have used radar and other noninvasive mapping technologies to document Holocaust sites across Europe, including the discovery, two years ago, of an escape tunnel at a Nazi death camp outside Vilnius.

Arriving at the pasture, we stepped out into the summer heat, and Reeder, tape measure in hand, walked along the edge, until he hit the 230-foot mark—the distance presented in an old newspaper account and the most reliable witness testimony, which placed the grave in the undergrowth just beyond the pasture.

The group cleared a search area, or grid, of 860 square feet. “Atsargiai!” someone shouted in Lithuanian. “Caution!” American students accompanying the scientists hauled out the brush, alongside the Lithuanian archaeologist Romas Jarockis, who had traveled with the group to offer his assistance. Nearby, Jol unpacked a bundle of ground-penetrating radar antennas, which would be staked at intervals of three-quarters of a foot each and would direct electromagnetic energy into the soil. The result would be a three-dimensional map of the earth beneath. From previous projects, and from his own archival research, Jol knew what he’d be looking for on the scans. “A lot of these pits were dug in the same way, in the same general shape,” Jol told me. “The Nazis and their collaborators were very particular, very uniform.”

When they were done, I walked toward the cars with Freund, whose family has roots in prewar Lithuania. “The main thing we want is closure,” he said.

That evening, in his hotel room, Jol uploaded the data to his laptop. “Right away, I could see something had been disturbed in the subsurface,” he recalled—a pit less than two feet deep. (Later, after consulting World War II-era aerial maps of the region, Reeder noticed a telling soil aberration in just this spot, further evidence that they’d found the grave.)

Freund and his colleagues almost never excavate burial sites, preferring to offer their data to local researchers. In this case, the officials in Rokiskis had little interest in disturbing the resting place of the Jaffes and Olkins—this confirmation was enough.

The next evening, the scientists and their students gathered on the edge of the road, facing the pasture. Freund had printed excerpts of Matilda’s poetry, in English and Lithuanian, and he wandered among the attendees, handing them out.

“Maciau tada ju asaras,” intoned Romas Jarockis. “Ir liudesi maciau...”

A University of Wisconsin student named Madeline Fuerstenberg read the translation: “Then I saw their tears, and their sorrow I saw...”

As the sun inched closer to the horizon, Freund produced a copy of a modified version of El Malei Rachamim, a Hebrew graveside prayer. “God, full of mercy,” he recited, “provide a sure rest for all the souls of the six million Jews, victims of the European Holocaust, who were murdered, burnt and exterminated.” He wiped tears from his face.

Later that week, Madeline Fuerstenberg walked into a tattoo shop in Vilnius, and presented the artist on duty with a line of text: He read aloud: “Her eyes are bright, full of light.”

Fuerstenberg pointed at a spot on her arm. She wanted the tattoo there, in a place where everyone could see it.

All poems and diary excerpts by Matilda Olkin appearing in this article were translated by Laima Vince.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated from the November 2018 print edition to include several factual clarifications.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/cc/8acc1d36-af65-42de-ab12-69c23333d7cf/nov2018_h13_lithuaniadiary.jpg)