11 Artists Capture What It Is Like to Live in a Megacity

“Megacities Asia,” a new exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, features 19 installations inspired by cities with populations of 10 million or more

In Boston, March means St. Patrick’s Day, an occasion that obligates convenience stores and supermarkets to stock up on green plastic party supplies. It’s a cultural quirk that worked out well for South Korean artist Han Seok Hyun, who arrived from Seoul in mid-March to find that curators at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts had procured a sizeable stash of emerald bric-a-brac. The raw material would supply the latest iteration of his series Super-Natural, a commission for the 146-year-old museum’s largest ever exhibition of contemporary art, “Megacities Asia.”

With two weeks left before opening day, Han quickly got to work, building a fanciful landscape out of green plastic bowler hats and sunglasses, green party cups, empty beer bottles and shimmering tinsel shamrocks. The American greenery supplemented crates of green products sourced in Korea: fake plants, pool floats, cans of aloe vera drink and packages of squid chips—all a testament to the universality of cheap consumer culture.

“In Seoul, most people live in apartments and survive through supermarkets,” said Han, whose work is a send-up of the idea that the color green means something is healthy and natural. “I see children say to their mother, ‘It’s Sunday! I want to go to the supermarket!’ I feel that’s weird! They should want to go to the playground.”

Han was born in 1975, in a South Korea that was emerging from post-war poverty to become one of the richest, most technologically advanced countries on Earth. He is part of a generation of Asian artists responding to massive changes that continue to transform the continent. “Megacities Asia,” which runs through July 17, features 19 installations by 11 of these artists, including Choi Jeong Hwa, also from South Korea, and the Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. They live and work in Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Delhi and Mumbai, each city with a population of more than 10 million people. These are places where forces like rural-to-urban migration, consumerism, technological development, pollution and climate change are dizzyingly apparent—and they may offer a glimpse into our global future.

A little more than a week before previews for the press and museum members were to begin, art handlers, translators and several recently-arrived artists were hard at work throughout the MFA’s sprawling complex. “It really is an all-hands-on-deck project,” said curator Al Miner, showing off an intricate spreadsheet the museum was using to keep track of who was supposed to be where, and when.

Delhi-based artist Asim Waqif was setting up his installation Venu (2012), which takes its title from the Hindi word for “bamboo,” a once common Indian building material that is falling victim to the vogue for steel, bricks and concrete. A network of bamboo and rope rigged with sensors that trigger sound and vibrations when a viewer approaches, Venu is an unlikely combination of traditional and high tech. “The viewer is not going to be able to tell whether it’s natural or artificial,” Waqif said. A former architect who decided he wanted to be more intimately involved with his materials, he confessed to finding “most museums really boring—it’s like there’s a barrier between the viewer and the art. But here, if somebody comes and explores, he’ll find many surprising things.”

In a corridor, visitors were already passing beneath Ai Weiwei’s Snake Ceiling (2009), an enormous serpent built from children’s backpacks to protest the Chinese government’s inaction after poorly-constructed schools collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, killing more than 5,000 schoolchildren. In the museum’s atrium, they stopped to study Ai’s sculpture Forever (2003), an elegant wreath of 64 interconnected bicycles, like those that once clogged China’s streets and are now being replaced by cars.

Upstairs, in an airy gallery normally dedicated to Buddhist funerary sculpture, a team of art handlers under the watchful eye of Chinese artist Song Dong assembled his Wisdom of the Poor: Living with Pigeons (2005-6). It’s a two-story house made up of old windows, bits of wood and other architectural detritus scavenged from Beijing’s traditional courtyard houses, whole neighborhoods of which are being erased as the Chinese capital becomes a modern metropolis.

Placing a contemporary installation in a room full of traditional artwork is an unusual move, but curators realized it felt right in the context of Song’s work, which is about Chinese history as much as the ancient stone steles and seated Buddhas that surround it. And it’s not the only part of the exhibition housed outside the white-walled basement gallery that the museum usually uses for special shows.

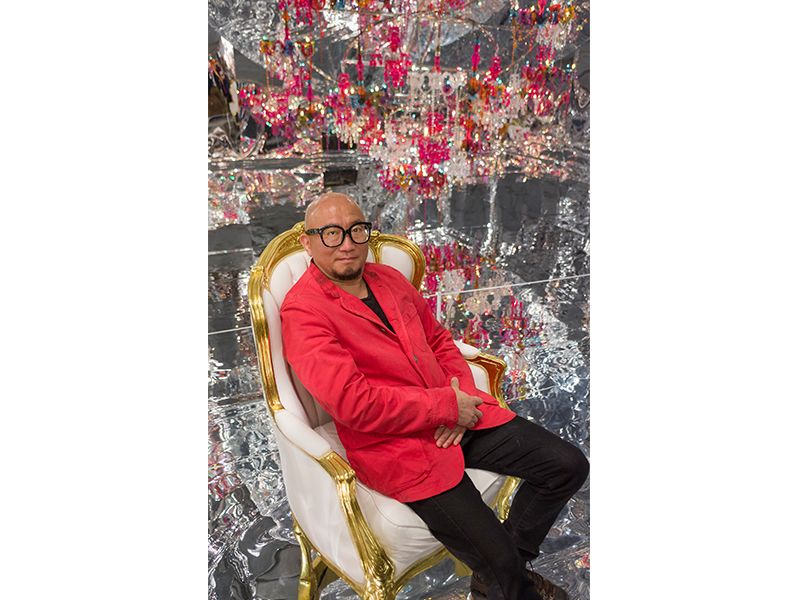

“Megacities” rewards exploration, just as cities themselves do. Poking around a quiet gallery of Korean decorative art, for example, the lucky visitor will stumble across a doorway leading to Seoul-based Choi Jeong Hwa’s Chaosmos Mandala. It’s a delightful space, with reflective Mylar-covered walls, ceiling and floor. An enormous chandelier, assembled from the cheap and ubiquitous candy-colored plastic that is Choi’s signature material, spins hypnotically overhead. Discovering it evokes the serendipity of wandering a city’s back alleys and finding an underground dance club, or a perfect hole-in-the-wall noodle shop.

“Almost everything in this exhibition encourages some kind of physical interaction,” noted Miner. Visitors can climb inside Song’s house, for example, and walk through Shanghai-based Hu Xiangcheng’s Doors Away from Home—Doors Back Home (2016), which combines scavenged architectural elements and video projection. “That interactivity reflects the pace and texture of city life,” Miner said. Of course, some of the best spots in a city are quiet corners where one can pause and take everything in. So in Chaosmos Mandala, visitors are invited to relax in a cream and gold armchair at the room’s center. (The museum accepts the inevitability of selfies.)

Other works offer a different sort of immersive experience. Hema Upadhyay’s 8’x12’ (2009) is a lovingly detailed model of Dharavi, one of Mumbai’s oldest and largest slums, which covers the ceiling and walls of a walk-in metal container. It is scaled to the average size of a home in this squatter’s community, where one million people live and work within less than a square mile. “You get a sense of what it’s like to be in a city like this,” Miner said. “You feel like you’re in this vast space, but you’re also physically constricted. It’s almost unsettling.”

Over the three years Miner and fellow curator Laura Weinstein were organizing the show, they visited the artists in their homes and studios and experienced firsthand the cities the exhibition explores. They toured Dharavi, visiting residents at home. It felt voyeuristic, Miner admitted, “but I also felt it was important to be there—to see it, to smell it.” In Seoul, the curators visited bustling market stalls where their artists scored raw material for found-art installations, and in a high-rise housing block outside Delhi, Miner marveled that “everything was bright and gleaming and new, as if it had sprung up out of nothing.” Each of the megacities was a web of contradictions—both teeming and lonely, chaotic and efficient, places of vast wealth and extreme poverty, where skyscrapers tower over sprawling shantytowns. It would take a lifetime to truly understand these places, but the exhibition’s artists make a valiant effort to evoke what it feels like to walk their streets.

Upadhyay was murdered by an associate in December, either because of a financial dispute or on the alleged orders of her ex-husband. One of her last works of art is a poignant installation commissioned specifically for “Megacities Asia.” Build me a nest so I can rest (2015) consists of 300 painted clay birds, each holding a scrap of paper with a quotation from literature. The birds represent migrants, who are moving to cities in increasing numbers, carrying with them their hopes and dreams for a better life. It’s a reminder that even cities with enormous populations are home to individual people, with their own private tragedies and triumphs—all affected, for good or ill, by the relentless tide of human history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)