At 40, MTV Is Officially Over the Hill

Born in 1981, the network soon grew to include reality TV and the VMAs. But nothing compares to its glory days of 24/7 music videos

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/e3/90e3b9aa-8f21-426e-aefe-ee498adcbafa/gettyimages-1336150870.jpg)

On March 27, 2021, roughly one year into the pandemic, “Saturday Night Live” opened with a cringey skit that mocked pandemic-era spring breakers as lusty, dead-eyed degenerates who had remorselessly triggered a coronavirus surge the previous year. “You’re watching MTV Spring Break live, at Miami Beach,” a voice-over announced, “where the party don’t stop until the government-mandated curfew!”

This image of MTV—washed up, hungover, and grimly partying on—has come to define the channel’s diminished relevance in 2021.

But when MTV first launched 40 years ago, it both captured and created the zeitgeist of teenage culture. For roughly two decades, audiences relied on MTV as a gateway to new music, fashion, experimental film and visual effects.

“A lot of these movements, consciously or unconsciously, came together in MTV,” says Smithsonian curator emeritus and visual music expert Kerry Brougher. “And then all of a sudden, they were in your living room.”

The Birth of MTV

By the late 1970s, the concept of a “video radio” television channel floated on the entertainment industry’s periphery. In 1975, Queen astonished audiences with a then-novel video for “Bohemian Rhapsody” on “Top of the Pops.” Two years later, songwriter Michael Nesmith, a member of the made-for-TV band The Monkees, became an early champion of the idea after making a cinematic video for the song “Rio.” As the ’80s drew near, music videos increasingly captivated television executives and radio producers who sensed their commercial potential.

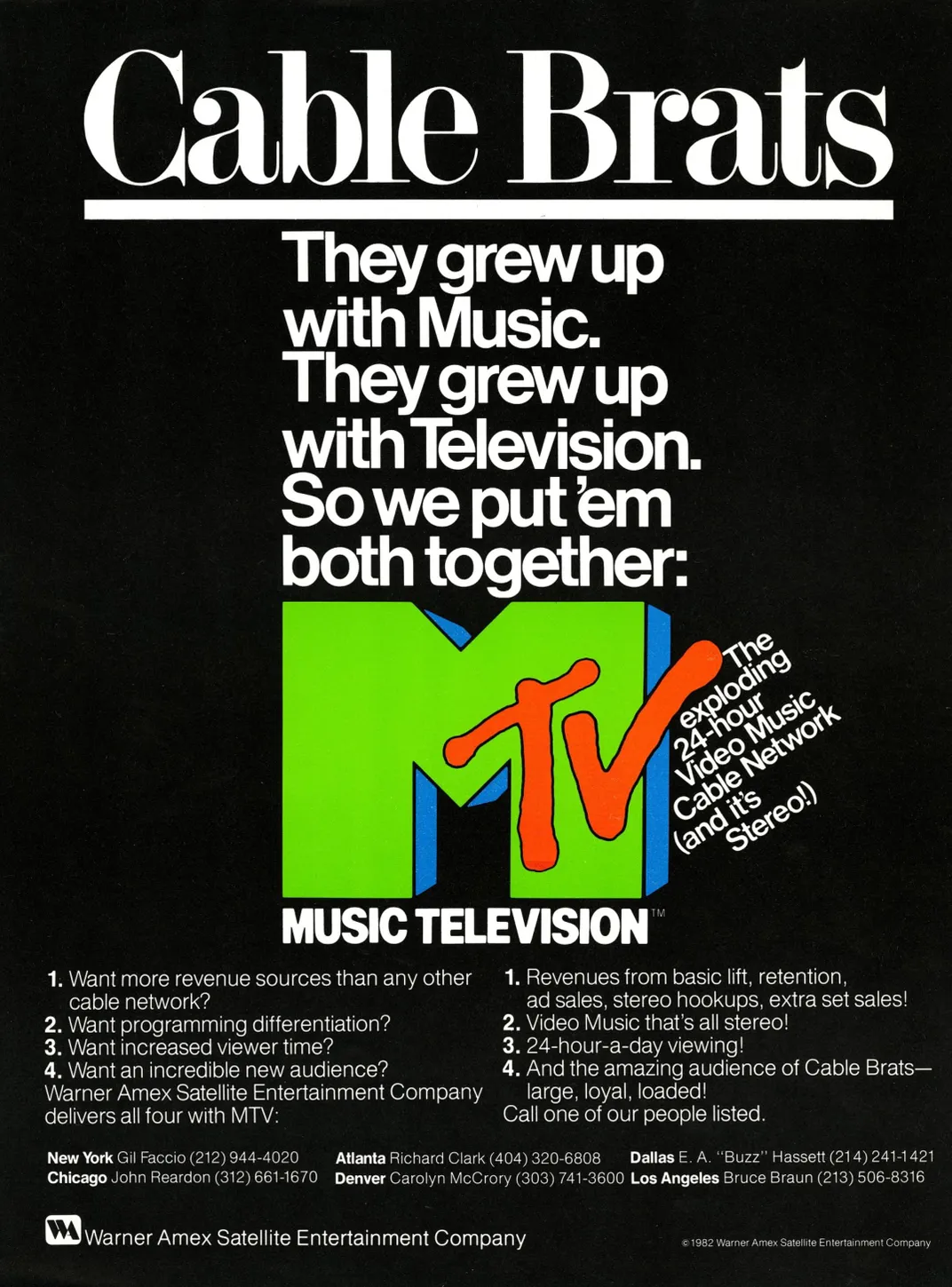

One such executive was John Lack, who’s largely credited with shepherding MTV into existence, according to I Want My MTV, an oral history by music journalists Rob Tannenbaum and Craig Marks. In 1979, American Express purchased half of Warner Cable Corporation for $175 million, forming a joint venture dubbed Warner-American Express Satellite Entertainment Company (WASEC). Lack was tasked by the venture with developing programming that would join The Movie Channel and Nickelodeon, which targeted adults and children respectively. To Lack and others at WASEC, teenagers were an overlooked—and potentially lucrative—audience.

On June 19, 1981, a brief New York Times column officially announced MTV’s arrival: The channel would be for “the big kids, the kind that get turned on by the big rock sound and the weird assemblages that make it.” MTV’s shrewd programming strategy relied on promotional music videos obtained from record labels entirely for free. Then, MTV planned to ply its teenage audience with advertisements for soft drinks, movies and beer, rotating the ads through different days and time slots in a radio-style strategy that rejected television advertising’s usual fixed schedule.

When MTV launched on August 1, 1981, cable infrastructure was so limited that MTV’s own staff had to cross the Hudson to a New Jersey bar that got the channel. There, they cheered as footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing rolled, followed by the Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star.” Viewers who managed to catch the premiere had seen nothing like it, and those who didn’t soon heard about it. As documented in I Want My MTV, musicians were equally dazzled. Stevie Nicks was “stupefied;” Dave Grohl felt it was “a transmission from a magical place.” Janet Jackson “loved watching it.” Heart’s Nancy Wilson remembers “craving it like crazy.” And Lenny Kravitz resembled countless American teenagers when he spent a family vacation ignoring Bahamian beaches, instead remaining glued to MTV in a hotel room.

Throughout the 1980s, MTV drafted pop stars including Cyndi Lauper, David Bowie and Boy George into assertive ad campaigns urging viewers to demand the channel from their cable operators. Audiences’ hunger for MTV reflected a larger shift in American television habits. By 1989, cable expanded to 79 channels and 53 million subscribers.

A surprise hit — and early misses

In 1983, David Bowie sat down with MTV VJ Mark Goodman. He was promoting “Let’s Dance,” then a No. 1 hit penned with co-writer Niles Rodgers, but Bowie instead wanted to discuss another topic. “It occurred to me, having watched MTV over the last few months,” he began, plucking at his sock, “that it’s a solid enterprise that has a lot going for it. I’m just floored by the fact that there’s so few Black artists featured on it.” Bowie fixed Goodman in his stare. “Why is that?”

Though it lasts just four minutes, the interview is excruciating. Goodman’s recycled corporate excuses seem mealy-mouthed and evasive, while Bowie’s body language conveys his skepticism as he leans back, brow furrowed. The clip has racked up 3.1 million views on MTV News’ YouTube channel.

According to Goodman, Bowie’s interview drew public attention to MTV’s conspicuous lack of Black artists—an issue some MTV staffers were already uneasy about behind the scenes. Since its launch, MTV had sidestepped accusations of racism by claiming its programming merely focused on rock music. Writing for a feminist academic journal in 1986, the New School’s Elizabeth Ellsworth and Margot Kennard Larson point out: “The fact that the groups that perform in MTV’s music videos are composed mainly of young, white males is not surprising since rock has historically been a white, male-dominated industry. Not only the musicians but the songwriters, technicians, engineers, producers and distributors are predominantly white males.” But instead of including Black artists, MTV played “basically, white R&B acts,” Goodman told Tannenbaum and Marks, contradicting MTV’s rock defense.

This manifestation of systemic racism is familiar to Krystal Klingenberg, a curator at the National Museum of American History and expert on global Black popular music. She cites Little Richard, today considered a gender-bending, boundary-pushing forefather of rock-and-roll, as a precursor to MTV’s racial biases. “Here you have somebody who was doing something really wild and bombastic and new and amazing,” Klingenberg says. Yet it was white singer Pat Boone who, in 1956, became “the big star, via essentially milquetoast versions of what other artists were doing,” she says, thanks to his access to mainstream media and distribution networks. Boone’s cover of “Tutti Frutti” climbed to number 12 on the charts, eclipsing Little Richard’s peak at number 17.

Klingenberg also points out that America has always devalued Black contributions to culture. “You can afford to not include as many Black artists if you don't see their work as being crucial to the pop cultural zeitgeist,” Klingenberg says. “And Black popular music, whether central or peripheral, has been critical to the pop musical zeitgeist in this country for a hundred years.”

Though countless Black artists shaped pop music, Michael Jackson ultimately prompted change at MTV. On May 16, 1983, more than 50 million television viewers watched Jackson perform the moonwalk on a broadcast—not cable—television special. But throughout that year, as Jackson gradually released music videos to promote his new album, Thriller, he was noticeably absent from MTV. According to In the Studio With Michael Jackson, CBS Records executive Walter Yetnikoff ultimately forced MTV to play “Billie Jean” by threatening to pull all CBS artists’ videos. In I Want My MTV, Yetnikoff recalls warning that he would publicly accuse MTV of snubbing Michael Jackson because of his race. Though “Billie Jean” and “Beat It” eventually broke into MTV’s heavy rotation, both quickly vanished, despite Thriller’s continuing tenure as a chart-topping success.

By November, one year after its release, Thriller had sold 20 million copies—sales so massive that the New York Times announced a comeback of the record industry at large. Jackson’s popularity was undeniable, and finally, MTV was eager to play another of his videos. To finance the extravagant monster-movie video for the song “Thriller,” director John Landis persuaded Showtime (then available in less than one million homes) to pay $250,000 to host the premiere. MTV paid $250,000 to show it second.

Creatively and commercially, “Thriller” was a triumph. By 1985, it had won a Grammy, three MTV Video Music Awards and the People’s Choice Award for favorite music video—and created a market for music videos on VHS. “Thriller” was also a turning point for MTV. On Christmas Day, 1983, the New York Times recapped pop music’s tumultuous year, noting that Michael Jackson “finally brought black music to MTV.”

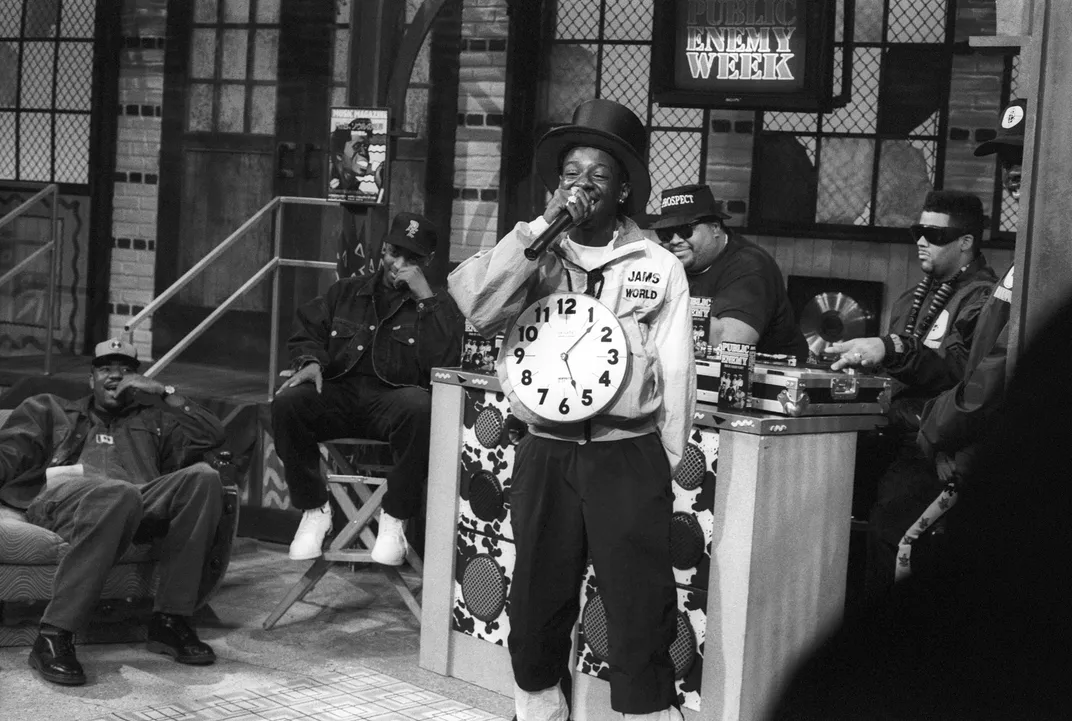

Still, it wasn’t until August 6, 1988—six years after MTV’s launch—that the channel finally aired a show that centered Black artists. Championed by production staffers Peter Dougherty and Ted Demme, “Yo! MTV Raps” premiered with rap and hip hop music videos, plus exclusive footage from a recent Run-DMC tour. In I Want My MTV, Judy McGrath, who eventually became the CEO of MTV Networks, recalled that the episode achieved astronomical ratings, topped only by the Video Music Awards and Live Aid.

“Yo! MTV Raps” brought NWA, MC Hammer, Tupac, Sir Mix-a-Lot and other iconic hip hop artists to the channel—but within MTV, misunderstandings among the predominantly white staff persisted. In I Want My MTV, staffers recall Michelle Vonfield, who enforced MTV’s content standards, objecting to the Heavy D lyric, “I’m not your H-E-R-B” because she mistook the slang for “nerd” as a marijuana reference.

Nonetheless, Klingenberg says “Yo! MTV Raps” made hip hop mainstream without compromising its authenticity. The show brought viewers directly into the Black, urban communities actively creating the genre. “It felt more interesting and engaging to have you immersed in the world where the music’s coming from,” host and hip hop artist Fab 5 Freddy told New York Magazine. “'Yo! MTV Raps' put hip-hop in every home,” host DJ Jazzy Jeff added. “That helped with the sales. That helped with the fan base. That helped everything grow.”

Why MTV abandoned music videos

By the 1990s, the novelty of music videos had finally worn off. From 1995 to 2000, MTV slashed its music programming by nearly 40 percent, replacing it with animated and reality shows directly portraying American teens.

In truth, MTV had long played non-music shows, starting with 1987’s game show, “Remote Control.” But 1992’s “The Real World” represented a new era. The idea was dreamed up by producers Mary-Ellis Bunim and Jon Murray, who put a cost-saving documentary spin on MTV’s directive to create a teen soap opera. From 500 applicants, MTV cast a studiously diverse group of seven teenagers, who became roommates in a New York City loft while the cameras rolled.

Over the course of 13 episodes, “The Real World” painted an intimate portrait of the minor dramas of roommate life, from squabbles over cleaning to occasional personality clashes and discussions of current events. “It started out as a surprisingly contemplative show that contained some of the most candid discussions of sex and race that I'd ever seen on television up to that point,” wrote NPR’s Linda Holmes.

Among the first season’s cast, Kevin Powell stood out for his unwillingness to shy away from conversations about race. “This country is racist as hell,” Powell bluntly told Andre Comeau, a white cast member. But the season’s most heated argument unfolded between Powell and Julie Gentry, an Alabamian who told him to “Get off the black-white thing!” The conversations were messy and palpably real. “Julie and I had the most famous argument in TV history on racism,” Powell recalled in “The Real World Homecoming: New York,” a March 2021 special that reunited the cast.

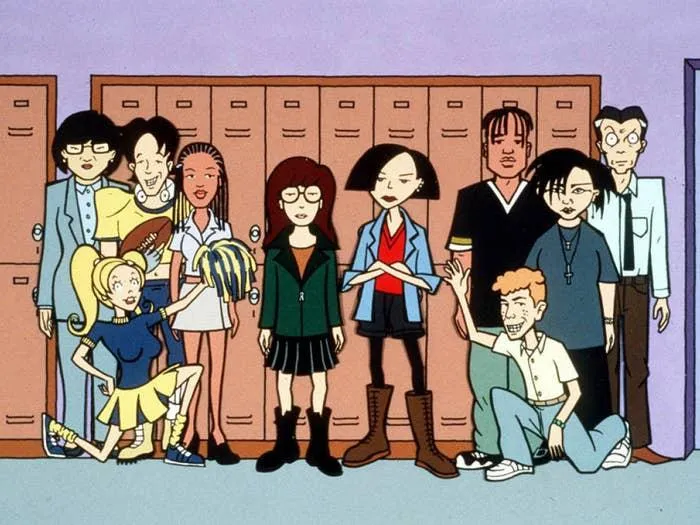

The 1990s also saw MTV’s animation department expand into a “creative laboratory” that debuted 16 original animated programs (more than any other decade in MTV’s history). Shows like 1993’s “Beavis and Butt-Head” were not only experimental, but also funny, subversive and often critically acclaimed.

This was particularly true of “Daria,” which followed its titular character as she navigated high school, family relationships, politics, race, and more. For many, particularly MTV’s female viewers, “Daria” captured the experience of discovering and defining a worldview and identity for the first time. “We were trying to process all those horrible things, in a lighthearted way,” showrunner and co-creator Glenn Eichler told Variety in 2017. “And let people exhale a little bit and say it’s not just me or thank god I’m not there anymore.”

Still, the creative and critical success of MTV’s experimental programming was always secondary to its commercial concerns. “The Real World” was soon joined by three additional reality shows, as well as dozens of comedy, news, competition and scripted shows including “Road Rules,” “The Ben Stiller Show,” “The Jon Stewart Show” and “The Challenge.” Reality shows consistently drew bigger audiences to MTV, particularly after YouTube launched in 2005 with its on-demand access to music videos.

As reality programming boomed during the 2000s, MTV churned out hits like “My Super Sweet 16,” which documented the lavish birthday bashes of spoiled rich kids, and “Jersey Shore,” a Real World-on-steroids that placed eight roommates in a house rigged with cameras. At their best, MTV’s reality shows were not only entertaining but impactful in teenagers’ lives. A 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research tied a 5.7 percent reduction in teen pregnancies to MTV’s “16 and Pregnant,” which followed the lives and struggles of young mothers. When new episodes aired, researchers saw spikes in internet searches for abortion and birth control, as well as fewer teen pregnancies in areas with high rates of viewership.

But MTV’s continued relevance was never assured. To some, a 2011 show called “Ridiculousness”—an abrasive version of “America’s Funniest Home Videos” curating viewer-submitted accidents and embarrassing moments—epitomizes its fall from grace. “Ridiculousness” occupied 113 hours of a 168 hour stretch of programming in June 2020, according to Variety. Soon after, The Ringer dismissively dubbed MTV “the 'Ridiculousness' network” after reporting the show ran uninterrupted for more than 36 hours straight. To Holmes, of NPR, it’s a missed opportunity. “MTV's reality programming isn't terrible now because it's reality programming,” she concluded. “It's terrible because it's terrible.”

Charting the fall of MTV through the VMAs

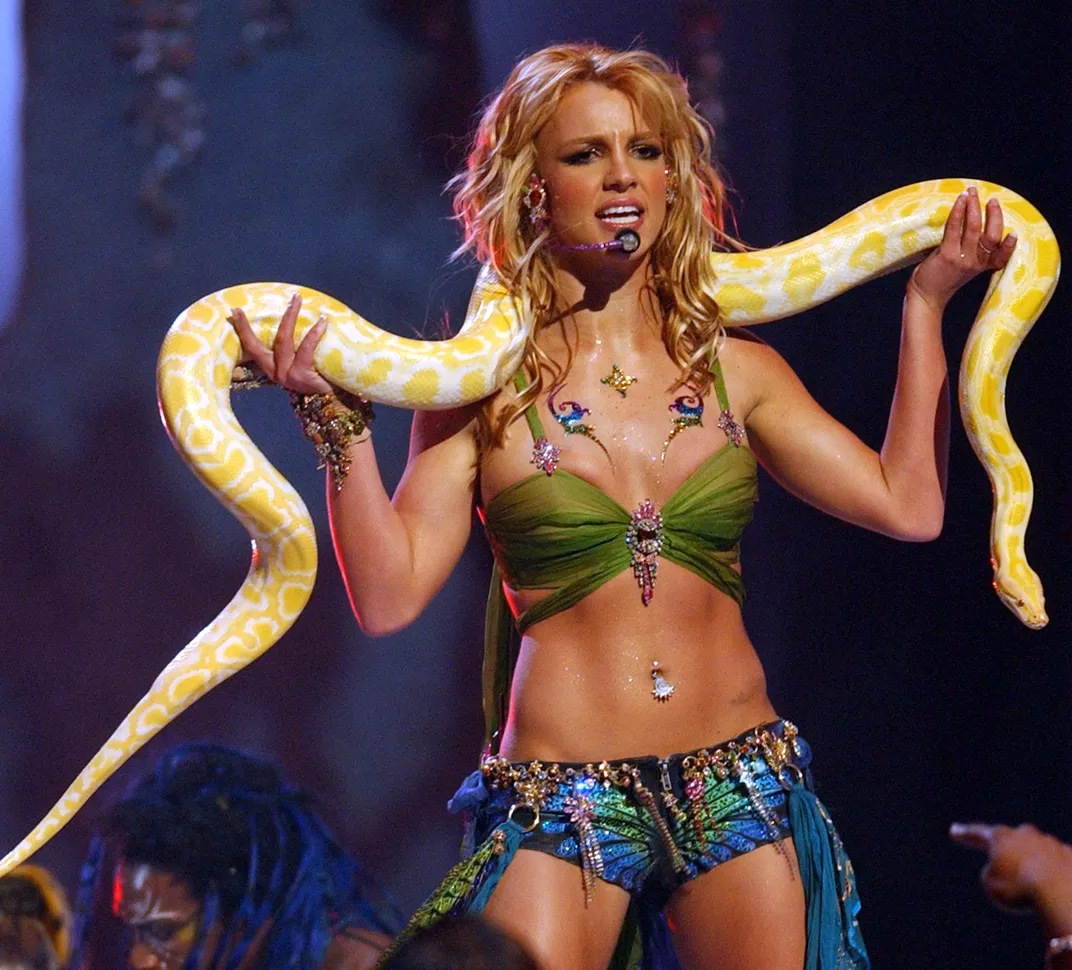

Across four decades of controversies, experiments and impact on pop culture, MTV’s annual Video Music Awards (VMAs) are perhaps the best measure of the channel’s reach and influence. First introduced in 1984, the VMAs were immediately destined to live on in pop culture infamy—thanks to Madonna, who burst out of a 17-foot-tall layer cake to perform “Like a Virgin.” Over-the-top behavior and fashion continued to captivate audiences, who tuned in to watch iconic pop culture moments unfold in real time. During the 2001 awards, Britney Spears performed “I’m a Slave 4 U” draped in a yellow Burmese python. In 2009, Kanye West hijacked Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech—a moment reminiscent of Courtney Love’s scene-stealing decision to pelt Madonna with a makeup compact during an red carpet interview at the 1996 VMAs. The momentum propelled MTV through to 2010, when the VMAs hit an all-time high of 11.4 million television viewers.

But even Beyoncé’s 2011 mid-performance pregnancy announcement and Lady Gaga’s 2012 meat dress couldn’t keep audiences tuning in forever. By 2012, VMA viewership plummeted by more than 50 percent to just 6.1 million viewers, then continued to hemorrhage for six consecutive years, dwindling to just 1.93 million television viewers in 2019.

In 2020, MTV touted that the VMAs’ “total minutes consumed” climbed by eight percent, adding up to 1.33 billion minutes of viewership across social media and other digital platforms. The metric is both a reflection of the streaming era and a distraction from the fact that the VMAs drew just 1.32 million television viewers, despite being simulcast across 11 ViacomCBS channels as well as The CW. As NBC and Disney launched their own streaming services, ViacomCBS instead distributed new and classic MTV programs on Comedy Central, Facebook Watch, Quibi, and Pluto TV, among others.

Today, it seems less likely than ever that MTV will return to its music-focused roots. Attempts to reboot “MTV Unplugged” and “TRL” were both short-lived. In 2016, MTV received a blitz of press attention for a show called “Wonderland” that promised to recenter music in MTV’s brand. But by 2017, “Wonderland” was gone, memorialized by a handful of videos and an abandoned Twitter account.

Yet music videos themselves continue to drive pop culture. In March 2021, Lil Nas X released a provocative video for “MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name),” inspiring conservative consternation with scenes of the artist pole dancing into hell. In a New York Times profile, writer Jazmine Hughes drew out Lil Nas X’s talent for referencing and reimagining moments that first appeared on MTV. The artist’s choreography and gold-spangled costumes at the BET Awards channeled Michael Jackson’s video for “Remember the Time,” Hughes noted. “But the final moments of this show, too, held a surprise, as Nas leaned over and made out with a male backup dancer.” The performance recalled the 2003 VMAs, where Madonna surprised Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera with a mid-performance kiss.

Though MTV is no longer the culture-defining behemoth it once was, its legacy continues to remain inextricable from pop culture, whether the current generation of teenagers tune in or not.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)