7 Epic Fails Brought to You By the Genius Mind of Thomas Edison

Despite popular belief, the inventor wasn’t the “Wiz” of everything

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/edisontinfoilphonographfeatured.jpg)

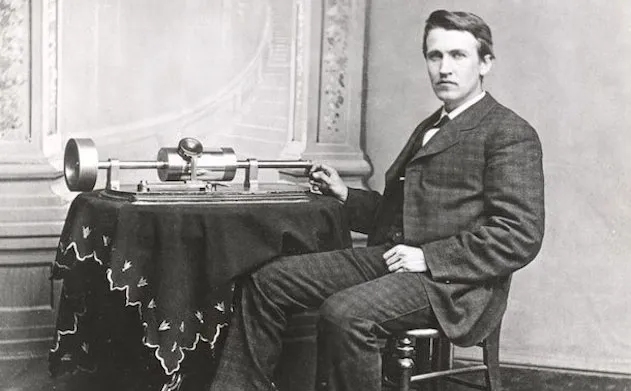

Almost everyone can name the man that invented the light bulb.

Thomas Edison was one of the most successful innovators in American history. He was the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” a larger-than-life hero who seemed almost magical for the way he snatched ideas from thin air.

But the man also stumbled, sometimes tremendously. In response to a question about his missteps, Edison once said, “I have not failed 10,000 times—I’ve successfully found 10,000 ways that will not work.”

Leonard DeGraaf, an archivist at the Thomas Edison National Historical Park, explores the inventor’s prolific career in his new book, Edison and the Rise of Innovation. The author offers new documents, photographs and insight into Edison’s evolution as an inventor, not to forget those creations that never saw wild success.

“One of the things that makes Edison stand out as an innovator was he was very good at reducing the risk of innovation—he’s not an inventor that depends on just one thing,” DeGraaf says. “He knows that if one idea or one product doesn’t do well he has others…that can make up for it.”

Chances are you haven’t heard of Edison’s botched ideas, several of which are highlighted here, because the Ohio native refused to dwell on them. DeGraaf says, “Edison’s not a guy that looks back. Even for his biggest failures he didn’t spend a lot of time wringing his hands and saying ‘Oh my God, we spent a fortune on that.’ He said, ‘we had fun spending it.’”

The automatic vote recorder

Edison, who made an early name for himself improving the telegraph, moved to Boston in 1868 to expand his network and find investors. By night, he worked the wires, taking press reports from New York for Western Union. By day, he experimented with new technologies—one of which was his first patented invention, an electrographic vote recorder.

The device allowed officials voting on a bill to cast their decision to a central recorder that calculated the tally automatically. Edison dreamed the invention would “save several hours of public time every day in the session.” He later reflected, “I thought my fortune was made.”

But when he took the vote recorder to Washington, Edison was met with a different reaction. “Political leaders said, ‘Forget it,’” DeGraaf says. There was almost no interest in Edison’s device because politicians feared it hurt the vote trading and maneuvering that happens in the legislative process (much in the way some feared bringing cameras to hearings, via CSPAN, would lead to more grandstanding instead of negotiating).

It was an early lesson. From that point on, DeGraaf says, “He vowed he would not invent a technology that didn’t have an apparent market; that he wasn’t just going to invent things for the sake of inventing them but…to be able to sell them. I have to suspect that even Edison, as young and inexperienced innovator at that point, would have had to understand that if he can’t sell his invention, he can’t make money.”

Electric pen

As railroads and other companies expanded in the late 19th century, there was a huge demand for tools administrative employees could use to complete tasks—including making multiple copies of handwritten documents—quicker.

Enter the electric pen. Powered by a small electric motor and battery, the pen relied on a handheld needle that moved up and down as an employee wrote. Instead of pushing out ink, though, the pen punched tiny holes through the paper’s surface; the idea was employees could create a stencil of their documents on wax paper and make copies by rolling ink over it, “printing” the words onto blank pieces of paper underneath.

Edison, whose machinist, John Ott, began to manufacture the pens in 1875, hired agents to sell the pens across the Mid-Atlantic. Edison charged agents $20 a pen; the agents sold them for $30.

The first problems with the invention were purely cosmetic: the electric pen was noisy, and much heavier than those employees had used in the past. But even after Edison improved the sound and weight, problems persisted. The batteries had to be maintained using chemical solutions in a jar. “It was messy,” says DeGraaf.

By 1877, Edison was involved in the telephone and thinking about what would eventually become the phonograph; he abandoned the project, assigning the rights to Western Electric Manufacturing Co. Edison received pen royalties into the early 1880s.

Even though the electric pen wasn’t a home run for Edison, it paved the way for other innovators. Albert B. Dick purchased one of the pen’s patented technologies to create the mimeograph, a stencil copier that spread quickly from schools to offices to churches, DeGraaf says. And while it’s hard to trace for sure, the electric pen is also often considered the predecessor of the modern tattoo needle.

The tinfoil phonograph

Edison debuted one of his most successful inventions, the phonograph, in 1888. “I’ve made some machines, but this is my baby and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age,” he once quipped. But getting a perfected machine to market was a journey that took nearly a decade—and plenty of trial and error.

Edison’s entrée into sound recording in the 1870s was in some ways an accident. According to DeGraaf, Edison was handling the thin diaphragm the early telephone used to convert words into electromagnetic waves and wondered if reversing the process would allow him to play the words back. It worked. At first, Edison modeled the invention on spools of paper tape or grooved paper discs, but eventually moved on to a tinfoil disc. He developed a hand-cranked machine called the tinfoil phonograph; as he spoke into the machine and cranked the handle, metal points traced grooves into the disc. When he returned the disc to the starting point and cranked the handle again, his voice rang back from the machine. (The machine even worked on Edison’s first test: the children’s rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”)

Reporters and scientists were blown away by the invention; DeGraaf argues it helped make Edison a household name. He took the device to demonstrations up and down the East Coast—even making a midnight visit to President Rutherford B. Hayes at the White House—and eventually organized exhibitions across the country.

Edison imagined music boxes, talking clocks and dolls, speech education tools and talking books for the blind. But without a clear marketing strategy, the device did not have a target purpose or audience. As the man who ran the exhibition tour told Edison, “interest [was soon] exhausted.” Only two small groups were invested in it, those who could afford to indulge in the novelty and scientists interested in the technology behind it.

The machine also took skill and patience. The tinfoil sheet was delicate and easily damaged, which meant it could only be used once or twice and couldn’t be stored for a long period of time.

When Edison revisited the machine 10 years later, he was more involved in both the marketing and the medium—which he eventually changed to a wax cylinder— and his invention took off.

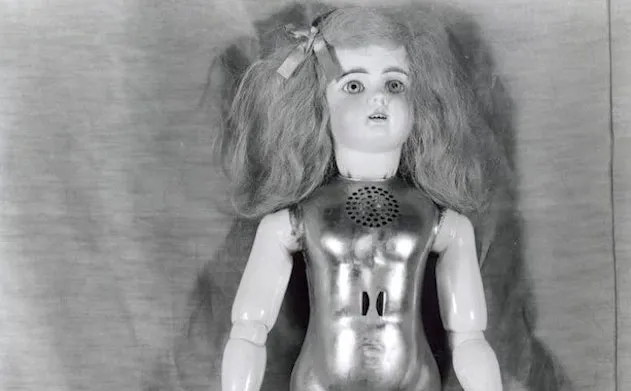

The Talking Doll

When he opened a lab in West Orange, New Jersey, in late 1887, Edison decided he wanted to turn out new inventions quickly and hand them over to factories to be manufactured and sold; what he earned from those sales would be put back into the lab.

“He didn’t want to do complicated things, he wanted to do projects he could turn out in a short time and [that would] turn a quick profit,” DeGraaf says.

Among the first of these attempts was the talking doll. (If you’ve ever owned a talking doll—and who didn’t love the pull-string Woody from Toy Story—you ought to thank Edison.) Edison crafted a smaller version of his phonograph and put it inside dolls he imported from Germany. He hoped to have the doll ready for Christmas 1888, but production issues kept the toys from hitting the market until March 1890.

Almost immediately, the toys began coming back.

Consumers complained they were too fragile and broke easily in the hands of young girls; even the slightest bump down the stairs could cause the mechanism to come loose. Some reported that the toy’s voice grew fainter after only an hour of use. Beyond that, the dolls didn’t exactly sound like sweet companions—their voice was “just ghastly,” DeGraaf says.

Edison reacted quickly—by April, less than a month after they were first shipped to consumers, the dolls were off the market. The swift move was one of the strongest indications of Edison’s attitude toward failure and how he operated when faced with it, DeGraaf says.

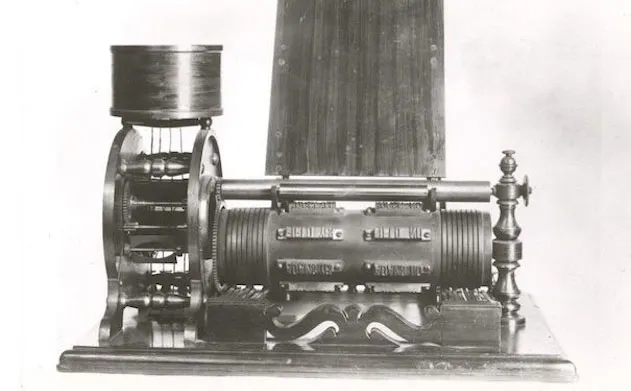

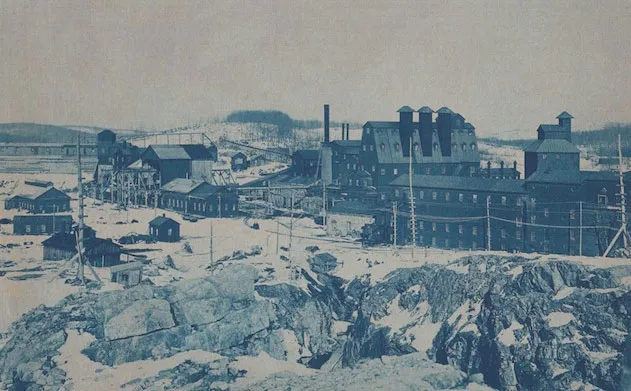

Ore mills and separators

For years, Edison corresponded with miners throughout the United States. The deposits of ore along the East Coast, Ohio and Pennsylvania were littered with nonferrous rock that had to be removed before the ore was smelted, DeGraaf explains. In 1890, Edison envisioned an ore separator with powerful electromagnets that could parse the fine ore particles from rocks, depositing them into two different bins.

But he wasn’t alone: at the same time, there were more than 20 small-scale ore separators being tested on Eastern iron beds. To give himself a competitive advantage, Edison constructed several large-scale plants he believed could process up to 5,000 tons of ore a day, DeGraaf says. After opening and closing a few small experimental plants, he constructed a plant near Ogdensburg, New Jersey, which gave him access to 19,000 acres of minerals.

Edison managed the plant in Ogdensburg—a change of pace for the inventor. The endeavor presented issues from the very beginning. The giant crushing rolls—5-foot by 6-foot tools Edison hoped would crush rocks up to six tons—that were crucial to the plant’s operations were all but useless when they debuted in 1894. As Edison redesigned them, his employees discovered the plant’s elevators had deteriorated, which meant he would have to rebuild an entirely new elevator system. Edison could never quite get the lab to full capacity. He rejiggered machines a dozen times over at all steps in the process, from crushing to separating and drying. The work came with a hefty price tag, with which Edison nor his investors could cover. Ore milling was a failed experiment Edison took a decade to let go—an uncharacteristically long time for the quick-stepping innovator.

The Edison Home Service Club

Before there was Netflix or Redbox, there was the Edison Home Service Club.

In the 1900s, Edison’s National Phonograph Co. rolled out a number of less expensive machines so people could bring entertainment—mostly music—into their homes. His and the other major phonograph companies, including Victor and Columbia, manufactured the machines as well as the records they played.

Edison believed his records were superior, DeGraaf says, and thought giving buyers access to more of his catalog was the only way to prove it. He rolled out the club in 1922, sending subscribers 20 records in the mail each month. After two days, they selected the records they wanted to order and sent the samples on to the next subscriber.

The service worked well in small clusters of buyers, many of them in New Jersey. Edison refused to let celebrities endorse his product or do much of any widespread advertising; Victoria and Columbia both had much more effective mass circulation advertising campaigns that stretched across the country, something that was “way beyond Edison’s ability,” DeGraaf says. “The company just didn’t have the money to implement [something like that] on a national scale.”

Up until this point, most markets were local or regional. “They’re not operating on a national basis and the success is contingent on very close personal relationships between the customer and the business person,” DeGraaf says—which is exactly what Edison tried to achieve with the club and other plans for the phonograph, including a sub-dealer plan that placed the records and devices in stores, ice cream parlors and barbershops for demonstrations, then tasked the owners with sending Edison the names of potential buyers.

The key to mass marketing is lowering the cost of a product and recovering profits by selling more of it—but “ that was a radical idea in the 1880s and 1890s and there were some manufacturers”—Edison among them— “that just didn’t believe you’d be able to succeed that way,” DeGraaf says.

“Mass marketing today is so ubiquitous and successful we assume it’s just common sense, but it’s a commercial behavior that had to be adopted and understood,” says DeGraaf.

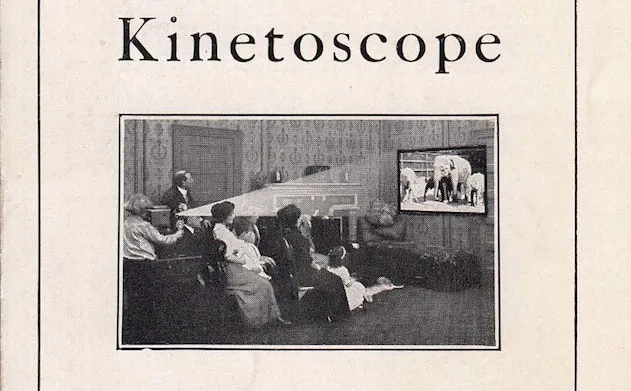

Home Projecting Kinetoscope

After early success with the motion picture camera, Edison introduced a motion picture projector for non-commercial use in 1912, with the idea they could serve as important educational tools for churches, schools and civic organizations, and in the home.

The machines were just too expensive, though, and he struggled to create a catalog of films that appealed to customers. Of the 2,500 machines shipped out to dealers, only 500 were sold, DeGraaf says.

Some of the kinetoscope’s issues mirrored the problems Edison encountered in other failed projects. “Edison is a very good hardware guy, but he does have problems with software,” DeGraaf says. The cylinder player that powered the tinfoil phonograph worked beautifully, for instance, but it was the disc that caused Edison problems; with home theater, the films themselves, not the players, were faulty.

Edison experimented with producing motion pictures, expanding his catalog to include one- and two–reel movies from documentaries to comedies and dramas. In 1911, he made $200,000 to $230,000 a year—between $5.1 and $5.8 million in today’s dollars— from his business. But by 1915, people favored long feature films over educational films and shorts. “For whatever reason Edison was not delivering that,” says DeGraaf. “Some dealers told him point blank, you’re not releasing films that people want to see and that’s a problem.”

“That’s part of the problem with understanding Edison—you have to look at what he does and what other people are saying around him, because he doesn’t spend a lot of time writing about what he’s doing—he’s so busy doing it,” DeGraaf explains. “I think he has impatience with that sort of navel gazing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)