Robotic Truck Convoys Could Change All Kinds Of Transportation

A Silicon Valley startup’s software automates how vehicles react to conditions on the road, offering new possibilities for fuel savings and efficiency

:focal(325x66:326x67)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/90/5a906907-d448-4809-8cbb-8628b7e3134e/trucks.jpeg)

Driving past a fleet of trucks on the highway is something that can make many motorists go a little white-knuckled, perhaps with good reason: There are about half a million trucking accidents each year.

But what if the trucks could react to—or even avoid—road hazards on their own?

Peloton Technology, a Silicon Valley startup, could make the roads safer for passenger vehicles and tractor-trailers alike by doing just that, with a new system that makes trucks “platoon,” or drive in tandem, and automatically react to impending accidents.

This type of driving, sometimes referred to as swarming, works similarly to other prototype systems tested by Volvo in Europe and the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization in Japan.

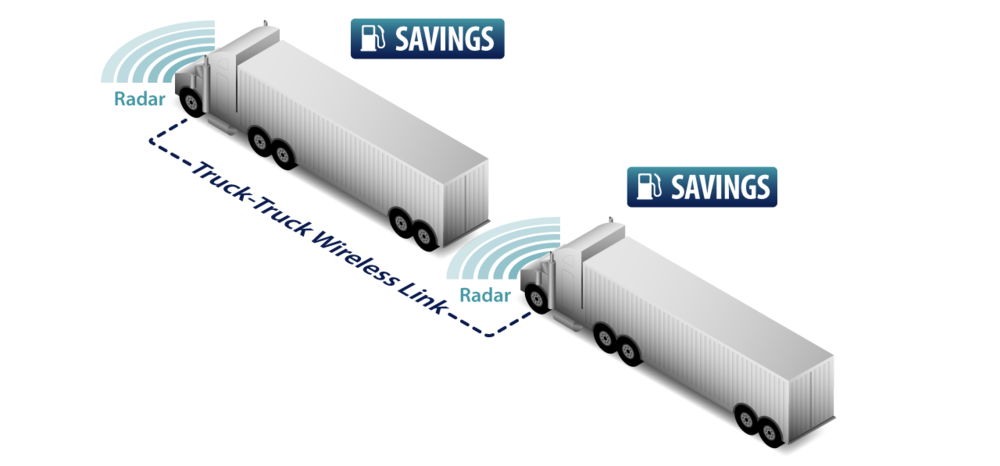

This isn't a "driverless" invention: Drivers keep their hands on the wheel, as the system doesn't steer, and the lead driver can use cruise control, or, independently accelerate or brake. On a single truck, the system operates much like the adaptive cruise control or active braking in many passenger cars. If traffic ahead slows, the truck will slow. If an obstacle suddenly appears on the road ahead, the truck will brake. When a pair of semis are wirelessly linked—over a radio frequency set aside for that very purpose by the Department of Transportation—the two appear to brake simultaneously.

The system, which doesn’t yet have a name or a price, can retrofit onto existing tractor-trailers. The system is tuned for the needs of trucks; Peloton isn't interested in any other industriesat the moment. But vehicle-to-vehicle communication is part of the larger self-driving car ecosystem that will need to be figured out before autonomous cars—like the one unveiled by Google—can safety navigate the roads.

“In our system, a truck in the rear is doing whatever the front truck is,” says Joshua Switkes, Peloton’s CEO. “The front truck is controlling the speed and is applying the brakes.”

According to Switkes, these automated systems react more quickly than a human driver ever could.

“A human will typically react within one to two seconds, and that’s in the best conditions. If there’s fog it can be much longer. We bring that time down to 0.001 seconds.”

It’s that speed that allows Peloton’s system to control two trucks at once.

A central operations center at the Peloton offices first determines whether or not current conditions allow for trucks to platoon. For instance, the system won’t allow a convoy to form in a city or when there’s heavy rain or fog. In those cases, the drivers will retain control.

The software also takes into account the size of each truck. A heavier truck with a more powerful engine will lead. The vehicle that can apply its brakes most quickly—the one with lighter cargo, for instance—will always follow.

The hardware on the trucks themselves is rather simple. Radar sensors mounted on the front of each truck monitor the road up to 800 feet ahead. That data is fed to an onboard computer, which is connected to the truck’s accelerator and brakes. The drivers also each have an LCD screen that shows the other’s point of view. For the rear driver, that means he or she can see the road ahead beyond the convoy; for the lead driver, it means visibility of his or her blind spots.

“We can put trucks closer together than would have been safe if people were manually driving,” Switkes says. Typically, a safe distance would be about 100 feet; Peloton has tested trucks as close as 36 going at speeds up to 70 miles per hour.

Traveling at such short distances helps improve fuel economy by using a technique known as drafting. Used most commonly by cyclists and race car drivers, drafting allows a trailing vehicle to take advantage of the wake cut by a leading one. Less resistance means the vehicle doesn’t have to work as hard to go the same speed. For the trailing Peloton truck, that means using about 10 percent less fuel.

There’s also a benefit for the lead truck. The large flat back of a trailer creates an area of low pressure behind the truck, which can actually pull the truck backwards. Having a second truck following close behind it helps smooth that air, making the low-pressure area smaller, and allowing the lead truck to use about 4 percent less fuel than it would otherwise.

Unlike other prototypes, Peloton’s is much closer to being road ready. Because the trucks still have human drivers and use a variant on existing active-safety technology, they’re not considered autonomous vehicles. That means the company can test and deploy them on public roads without the special permit required for companies like Google testing driverless cars. For now, the company is focused on creating platoons of only two trucks, but has already completed thousands of miles’ worth of successful tests on public highways, it says. Most recently, a pair of trucks navigated a stretch of open highway on Interstate 80 outside Reno, Nevada.

Peloton will begin pilot programs with a few truck fleets, none of which they’re currently at liberty to name, in the coming months. They aim to have the system ready to sell in mid-2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/me.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/me.jpg)